Sabato tregua (Saturday’s truce) by Andrea Bruno

Deregulated financial capitalism immersed Southern Europe in a deep social, economical, and political crisis. The euro’s cohesion is at stake at the moment while PIGS countries (hail racism!), especially Greece, see their sovereign debt credit ratings descend into garbage (PIGS countries are: Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain; in 2008 the acronym became PIIGS with the inclusion of Ireland). IMF imposed restrictions choke the economy provoking unemployment. On top of that grim scenario Globalization dislocated factories from the so-called first world to become sweatshops in the so-called third world (if you think that slavery doesn’t exist anymore, think again…). Entire communities were destroyed with millions of unemployed people from all over the world (add post-colonial and post-communist to post-industrial) flocking to the major cities in search of a life. This created huge social problems with riots in France, for instance. Riots in Greece are part of everyday life by now…

These are, in a nutshell, our difficult European times. Any artist worth his or her salt should acknowledge them one way or the other. That’s what Italian comics artist Andrea Bruno eloquently does…

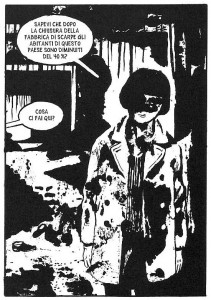

Panel from Sabato tregua (see below). Canicola, 2009. Not paginated.

Sabato tregua is a big format book (18,5 x 12 inches, give or take) reminding two other similar experiments: French Futuropolis’ 30 x 40 [cm] collection, U.S.A’s Raw, in its first series incarnation (both appeared during the eighties). It was published by the art collective from Bologna, Canicola (“Cannicula,” or the star Sirius which announces the hottest days of Summer). Andrea Bruno had the idea to revive this huge format; another book (Grano blu – blue wheat -, by the great Anke Feuchtenberger), was already published in the same format. In case that you’re wondering, Canicola’s books have a (not very accurate, sometimes…) English translation at the bottom of the page. In the image reproduced above the character that is off-panel, Mario, says (I transcribe from the book’s translation):

What are you doing here?

While Christine, says:

Did you know [that,] since the shoe factory closed[,] the population of this town has decreased by 40%[?]

And, then, she continues:

Once it was a workers’ town, now it’s a thieves’ town. When a robbery happens in the nearby towns, the police come[s] here immediately to start the[ir] search.

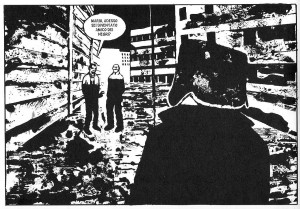

While Christine speaks there’s a three panel zoom in that ends in a medium shot. Conversely Mario’s face is hidden most of the time by melancholic shadows. The same thing happens to other characters, but it’s not only that: Andrea Bruno’s “dirty” style disintegrates the physical world to mirror the disintegration of post-industrial communities.

Sabato tregua: “Let’s go”: a melancholic view of the world under capitalism.

Another disintegration occurs to the story. Andrea Bruno says a few interesting things about this particular aspect of his work:

What do we mean by “linear discourse?” The storyline, the plot may not be the only way to unify a narrative? Maybe images, signs and moods can also become the parts that “sustain” a story and give it an identity. I try not to do “antinarrative” comics, but I don’t like to draw stories that tell it all.

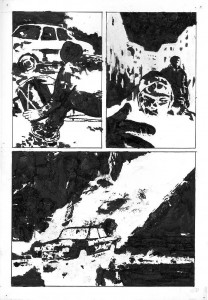

Andrea Bruno presses ink soaked cardboards to the surface of his drawings. He uses white paint almost as much as he draws and paints with black India ink. The result is a very distinctive graphic style in which chance plays a part, blobs are as important as lines and the white surfaces are as important as the black ones. White, as in Alberto Breccia’s drawings (the old master has to be cited), is pretty much an active part of Andrea Bruno’s drawings, not just negative zones…

Anni luce (light years), original art, Miomao Gallery, 2007. A car is burned during a riot. A violent technique to depict violent acts.

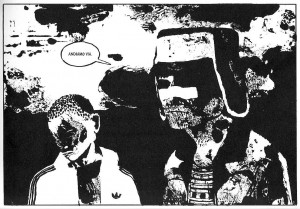

Wherever millions of famished immigrants go xenophobia and racism follows them. Here’s what Andrea Bruno has to say about it:

I try to suppress the surface of well being, of the main fashions and customs, to show landscapes and relationships reduced to the bone. The denunciation is not direct, it’s more in the presuppositions than in what I choose to show. I prefer the peripheral vision. Racism and inequality, in my comics, are not denunciated, but appear as ‘normal,’ so to speak. The effect renders them, maybe, even more hateful.

Sabato tregua: “Mario, [are you] a friend [of the] niggers, now?”

Andrea Bruno appeared in English in Suat’s Rosetta # 2.