This is the first of a two part essay. Part 2 is here.

__________________

Anyone who has heard of Before Watchmen probably knows something about the related controversy even if they haven’t read a single issue of the series. Despite attempts by DC to present the series as the official prequels to Alan Moore’s and Dave Gibbons’ mid-1980s classic Watchmen, many fans of the original have questioned the necessity and legitimacy of the prequels. It didn’t help DC’s credibility much that both Moore and Gibbons have spoken out against the series. Moore fiercely denounced it as a cynical exercise in greed and stupidity (e.g. Amacker), while Gibbons described it as being “really not canon” (Yin-Poole par.17).[i] After ten months, nine titles and 37 issues, the series finally ended in April with the publication of the final issue. However, this probably isn’t the last we have heard of Before Watchmen: DC has scheduled to relaunch the series in a four-volume collector’s edition in June and July.

While the series might not have been the unequivocal success that DC was banking on, one creator seems to have risen above the controversy to receive both popular and critical adulation. The creator’s name is Darwyn Cooke. Cooke is writer and artist of the six-issue Minutemen, and writer of the four-issue Silk Spectre, illustrated by artist Amanda Conner. A survey of the major reviews of Minutemen and Silk Spectre reveals that almost every critic has something positive to say about them.[ii] Grant Morrison has singled them out for praise—“Amanda Conner’s stuff is brilliant … and Darwyn Cooke’s Minutemen is great” (Sneddon par.42)—and a few commentators have even gone so far as to call the books worthy additions to the Watchmen universe.[iii] About this overtly positive consensus I believe something must be said. While I agree with the majority of critics that the quality of the art work in Minutemen and Silk Spectre is beyond reproach, I have deep reservations about the tenor and preoccupations of Cooke’s writing. Given the almost universal acclaim enjoyed by Cooke’s titles and the willingness of so many critics to accept his revision as worthy of Moore and Gibbons, I believe it is important that a clear dissenting case be made.

Watchmen, Deconstruction, Reconstruction

To address the problems of Cooke’s revision, it is useful to reiterate what Watchmen was “about”. Watchmen has been called a “deconstruction” of a traditional superhero comic (e.g. Thomson). While the term is overused, it still aptly summarizes the intent of Moore and Gibbons. In brief, deconstruction refers to a critical strategy aimed at exposing the unquestioned assumptions and internal contradictions in a traditional discourse. The target of Watchmen’s deconstruction is specifically the heroic power fantasy offered by traditional superhero comics. The question “Who watches the watchmen?” not only invites readers to consider the real-world implications of power abuse by “heroes” who have appointed themselves the world’s guardians, it also appeals on a meta-textual level to the same readers—those literal “watchmen” watching the pages of the story unfold—to be self-critical about their consumption of such heroic power fantasy.

And make no mistake about it: traditional superhero comics cater mostly to the heroic power fantasy of heterosexual males. Part of Moore’s and Gibbons’ campaign in Watchmen was thus to disrupt the expectations and prejudices of this dominant demographic. Instead of a linear story supporting a singular heterosexist worldview, Watchmen’s narrative is deliberately ambivalent and multilayered, including subplots, digressions, time shifts, alternate scenarios, allusions, parodies, and addendums. The intent is to challenge the monolithic notion of “heroism” and explore the richness and complexity of ordinary, unheroic lives. In addition, the book explicitly deflates the heterosexual male ego by presenting a catalogue of unheroic males. Rather than aspirational figures such as Superman, Batman, Wolverine, the readers are presented with “heroes” in the shapes of a narcissist, a rapist, a zealot, an impotent and an H-bomb. The fact that so many readers have still read some kind of fantasy antihero into Rorschach has earned an appropriately scornful response from Moore.[iv]

On the surface, Cooke’s projects appear to be attuned to Moore’s and Gibbons’ deconstructive spirits. He mentioned in an interview that Minutemen deal with hard-core topics such as “homosexuality, sadism, opportunism, greed, self-interest” (Truitt par.18). But then he felt the need to add this: “because it has to have it in order for me to be passionate about it, somewhere in the kernel of it is the heroic ideal” (Truitt par.18). And herein lies the problem. Cooke’s interest is not in deconstruction but in reconstruction, i.e. reaffirming the conservative, nostalgic moral paradigm of a traditional heroic power fantasy. Whereas Moore was interested in demolishing heroic stereotypes in order to explore the humanity beneath, Cooke is more interested in reinforcing stereotypes in order to prescribe for humanity what is and isn’t heroic. Under Cooke’s revision, a critique of heroic constructs has reverted to a defence of heroic constructs. This makes Minutemen and Silk Spectre, in my opinion, a diverting misappropriation at best and a grotesque travesty at worst. I have chosen to examine three areas: (i) the stereotyping of sexual minorities in Minutemen, (ii) the whitewashing of heterosexist violence in Minutemen, and (iii) the affirmation of paternal authority in Silk Spectre.

Reconstruction 1: Lesbian Martyrs and Gay Villains

The original Watchmen was ground-breaking in its depiction of sexual minorities. Moore has long been a supporter of gay rights (e.g. Gaines), and his explicit inclusion of gay characters could be seen as an expression of this support. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to expect from Moore any didactic portrayal of gay people as “positive role models”. Moore’s gay men and women are diverse, complex and flawed—just as people are in real life. His characters aren’t one-dimensional caricatures and their individualism, autonomy and rights to exist are taken for granted.

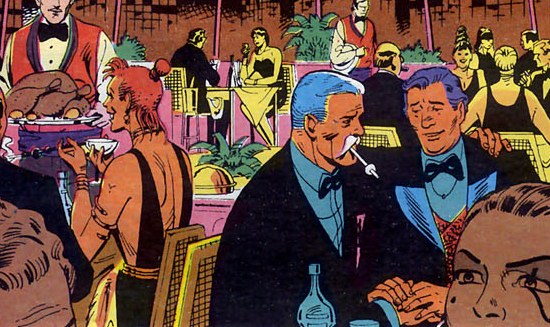

In Book 1 of Watchmen, Moore did something unprecedented in a mainstream superhero comic: he includes a normative image of a gay couple holding hands in public (Figure A1).[v]

The image explicitly normalizes homosexuality and challenges the genre’s tradition of making gay men invisible, risible or abominable. The placement of the gay diners in the midst of the “hero” and “heroine” Dan and Laurie expresses Moore’s egalitarian argument that everyone is a hero in his or her own story, and the lives of non-traditional ordinary folks are just as important as the lives of traditional superheroes.[vi]

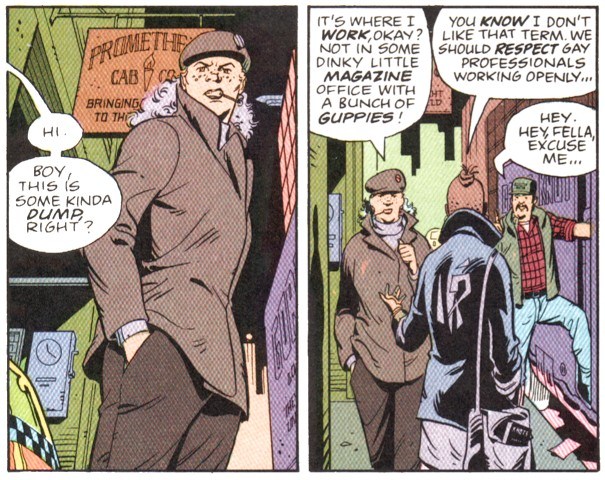

Moore took this concern further by including among his minor characters a dysfunctional lesbian couple. The remarkable thing about the couple Joey and Aline (Figure A2) is that they embody everything that traditional comic book readers are likely to find objectionable in women: loud, assertive, opinionated, and so butch-looking that people call them “fella[s]”.

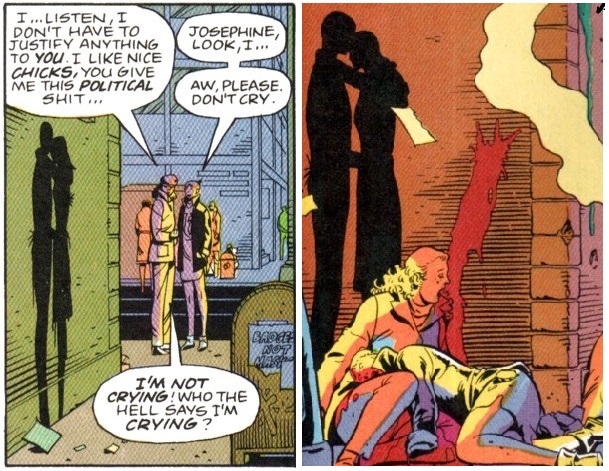

Joey especially is rude, bossy, prone to violent outbursts, and even physically assaults Aline in public. Yet, by taking an interest in these women and depicting them against the “Hiroshima lovers” shadow in the context of Adrian’s alien attack (Figure A3), Moore rewrote the comic book assumption that such people are unimportant and have no rights to exist. Their deaths are a reminder that every life is a “thermodynamic miracle” and an indictment of the type of heroic ego that would justify mass murder as a master plan.

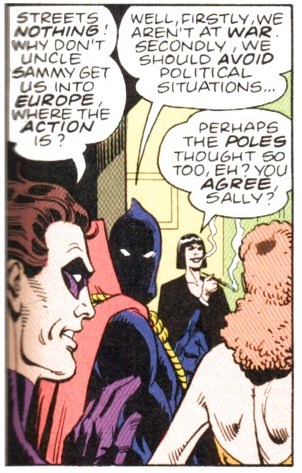

The same conviction applies to Moore’s exploration of superheroes. Rather than perpetuating the myth that superheroes are heroic heterosexuals, he saw that dressing up to fight crimes is more likely to be psychologically appealing to outcasts and minorities. Accordingly, he made three of the eight original members of the Minutemen gay. Silhouette/Ursula Zandt is the lesbian in the group. Although Ursula as a character barely exists in Watchmen, what we saw of her suggests she is the opposite of conventional. As drawn by Gibbons, she has a sharp, angular face, an androgynous haircut, wears a kinky black leotard and smokes a phallic cigarette. That her only line in the book is a sarcastic jibe about Sally’s Polish heritage (Figure A4) suggests that she wasn’t meant to conform to any “nice girl” stereotype.

Cooke said in an interview that Ursula is “the hero” of Minutemen (Truitt par.12). It is possible that his take on Ursula is inspired by the character of Valarie Page in Moore’s other masterpiece, V for Vendetta. Yet, whereas Moore had the good sense to give Valarie an independent voice and make her an inspiration to another woman, Cooke does something far less inspiring with Ursula: he refashions her into a romantic martyr and erotic fetish for straight men. He claimed without a hint of irony in the interview: “[P]eople are really going to dig her” (Truitt par.13). As drawn by Cooke, Ursula has become a petite, chicly dressed and conventionally attractive young woman (Figures A5-6), and her main function in the book is to serve as the “conscience” of Minutemen and an object of unrequited love for the straight male narrator, Hollis Mason.

In other words, Moore’s attempt to shake up the genre by challenging readers to take notice of the kinds of gay characters they wouldn’t expect to see in a superhero comic is sabotaged by Cooke in favour of a hetero-friendly paradigm about hot-looking lesbians and hot-blooded straight men. In Book 2, Ursula finds sanctuary in a Catholic church after being wounded by a stray bullet during her investigation of a paedophile ring. Had Moore written the scene, no doubt he would have recognized the Catholic Church as an institution plagued by its own child abuse problems and developed an argument that calls into question any simplistic dichotomy of “good” and “evil”. Yet, such social, historical and philosophical inquiries seem beyond the scope of the literal-minded Cooke, who piles on the religious sanctimony and romantic clichés instead (Figure A7).

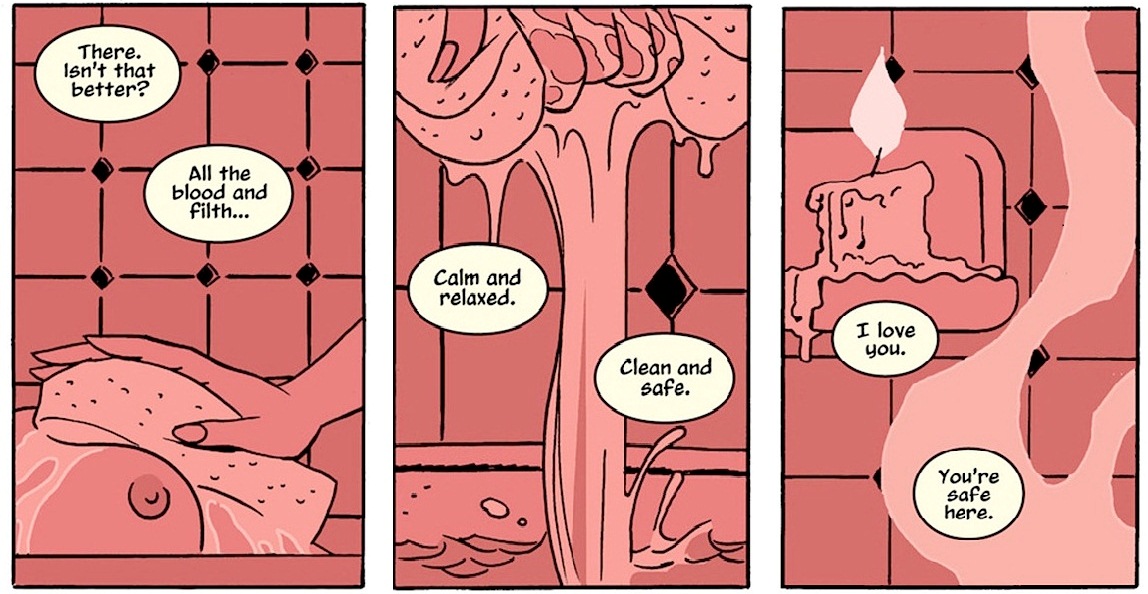

Ursula appeals to a statue of Christ to “love [her]”, and Christ answers her call by sending her an “angel” in the person of Hollis. The writing is mawkish to the point of being embarrassing: “He picked me up and bore my burden, and he told me to be still. He told me he loved me”. If the spectacle of a knight in shining armour rescuing a damsel in distress isn’t clichéd enough, Cooke’s decision to punctuate the sequence with soft-porn images of Ursula being bathed by her lover Gretchen (Figure A8) makes clear his strategy of treating lesbianism as a delectable spectacle for straight men.

Just as lesbianism is treated as a straight romantic fetish, so male homosexuality is treated as an object of abomination. Bizarrely, Cooke appears to think that romanticizing lesbianism has earned him a license to gay bash with impunity. While Moore’s Nelson Gardner/Captain Metropolis and Hooded Justice were hardly paragons of virtue,[vii] nothing in Watchmen prepares one for the hatchet job done on them in Minutemen. Cooke has rehashed almost every negative gay stereotype in his jaundiced revision of these characters. Nelson is a nincompoop, a publicity whore, a drama queen, a pillow biter; Hooded Justice is a sadist, a murderer, a rapist, a suspected serial paedophile. Cooke has no interest in exploring or understanding these men’s history, relationship and psychology. Instead, every book puts forward sensational scenarios to consolidate their corruption, hypocrisy and monstrosity:

- In Book 1, Nelson and Hooded Justice mastermind a mission that leads to the wrongful burning of a firecracker factory. They shamelessly present their mistakes to the public as a successful intervention of a firearm smuggling operation.

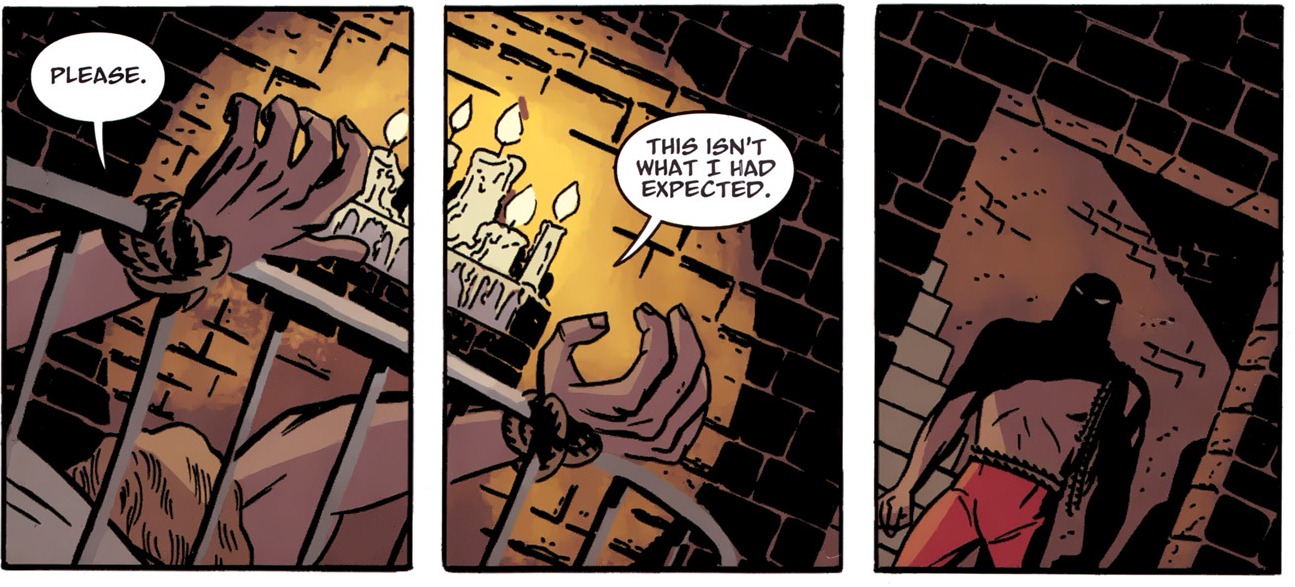

- In Book 2, Nelson is tied up and raped by Hooded Justice (Figure A9). This sinister sequence is intercut with Hollis’ and Ursula’s investigation of a circus where children are known to go missing, which establishes an explicit link between sadism, male homosexuality and paedophilia.

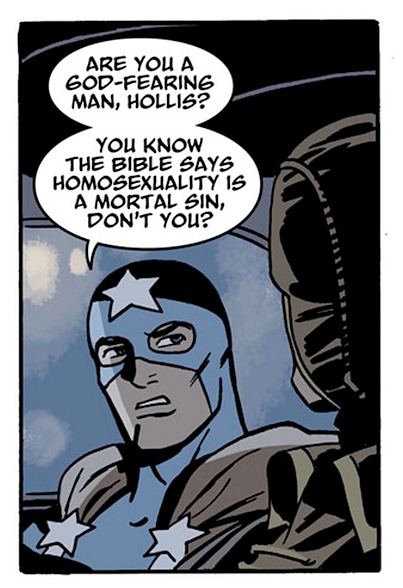

- In Book 3, Nelson sends his new toy boy lover to intimidate Hollis into dropping his plans to publish Under the Hood. Cooke legitimizes the straight male disgust at homosexuality by gratuitously turning Dollar Bill into a spokesman for homophobia (Figure A10). Bill tells Hollis: “I’ll be listening to Metropolis, and I’ll suddenly be thinking about him and Justice and it makes me kind of sick to my stomach”—an attitude Cooke pointedly refrains from disavowing or ironizing.[viii]

- In Book 4, Nelson and Hooded Justice hypocritically expel Ursula from the Minutemen, and go hustling in “boy’s town” rather than bringing Ursula’s killer to justice. It takes Sally in her kick-ass mode to hunt down and take out the killer. Sally is disgusted by the gay men and tells them contemptuously: “You two should be doubly ashamed. You call yourselves men? Clean up this mess. It’s all you’re good for.”

- In Book 5, Nelson and Hooded Justice lead a heroic duo Bluecoat and Scout to their deaths in a mission to foil a Japanese terrorist plot to launch a nuclear attack from the Statute of Liberty. Bluecoat and Scout are revealed to be a father and son team, and their selfless heroism contrasts sharply with the corrupt egotism of the gay duo.[ix]

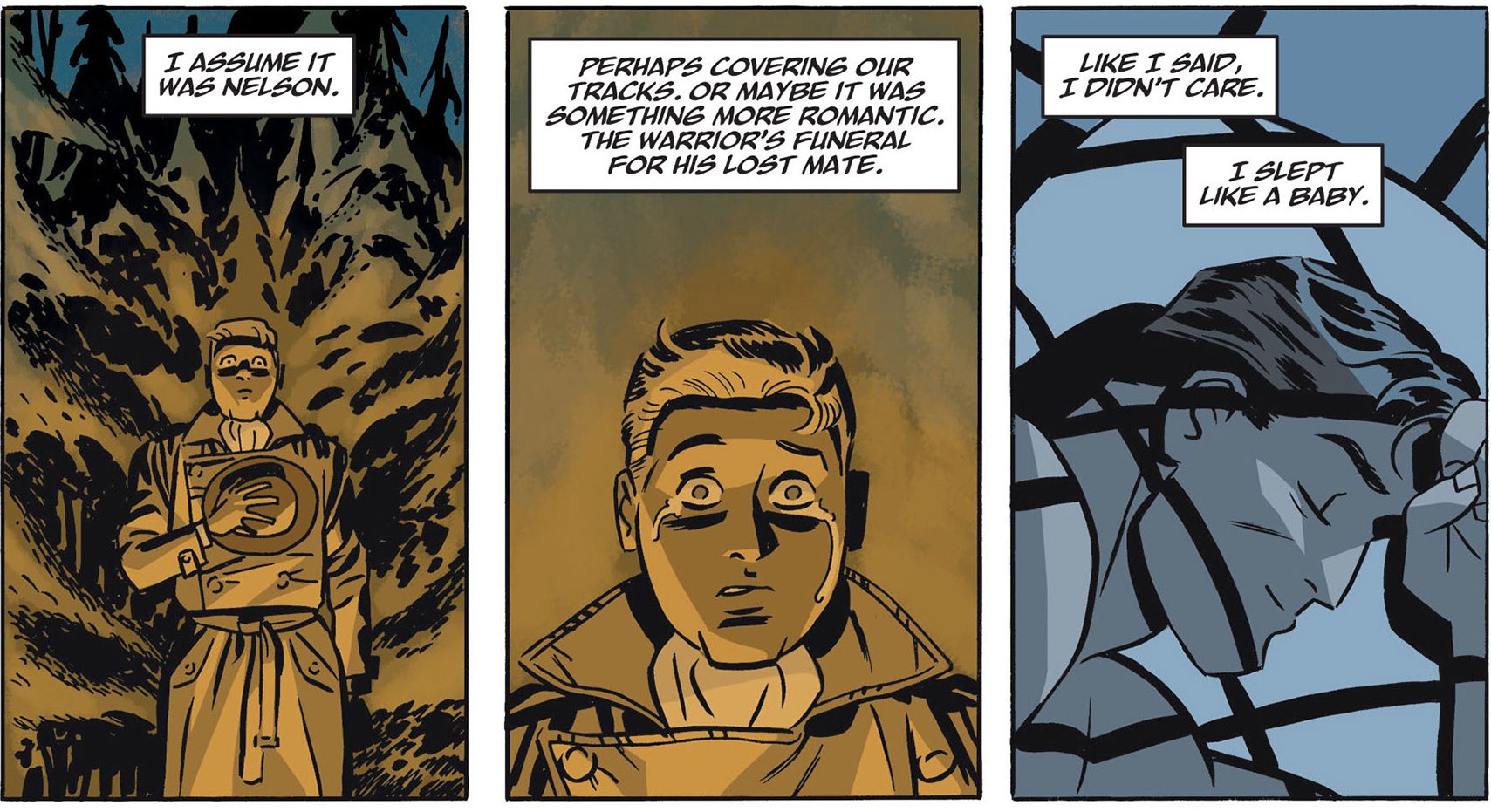

- In Book 6, Nelson wallows in self-pity and betrays Hooded Justice by revealing his hideout to Hollis. After Hollis hunts down and kills Justice, Nelson “screech[es]” like a drama queen and blows up his compound ala Edgar Allan Poe’s “Fall of the House of Usher” (Figure A11) while Hollis helps his injured “best friend” Byron/Mothman away.[x] The insinuation is that Nelson is a self-pitying degenerate destined to spend the rest of his life alone, whereas Hollis can look forward to being a surrogate father to Sally’s daughter and a mentor to the neighbourhood’s kids.

Reversing Watchmen’s subversion of conventional morality and sexual stereotypes, Cooke has reconstructed a good-versus-bad dichotomy in which a fetishized lipstick lesbian represents “good”, two despicable gay men represent “bad”, and a noble straight man represents “normal”. In this way, he has undone much of Moore’s and Gibbons’ progressive depiction of sexual minorities and replaced it with some banal heterosexist clichés.

Reconstruction 2: Macho Antihero and Legitimate Rape

Another revolutionary aspect of the original Watchmen was its deconstruction of the genre’s valorization of aggressive masculinity. Some examples of this type of “macho antihero” are Conan the Barbarian, the Punisher, Wolverine, Deadpool, and just about any male protagonist from a Frank Miller comic. The heroic power fantasy projected by this macho antihero stereotype explicitly pampers the male readers’ ego, so it follows that one of the macho antihero’s essential attributes is his sexual aggression towards women. In the course of the macho antihero’s adventure, he is expected to bed many women and break many female hearts; he is just too much of a stud to tie himself down to one woman.

Even such fantasy tends, however, to draw a line between sexual aggression and actual rape. While the macho antihero’s code of honor usually allows him to rough-handle women (e.g. pinching their butts; shoving them aside in battles; knocking them out “for their own good”), very rarely would the macho antihero be depicted as a rapist: a role reserved for villains.[xi] The underlying assumption is that the macho antihero doesn’t need to rape; he can work his way up the skirt of any attractive female who isn’t already throwing herself at him. Besides being sexually endowed, the macho antihero is a rough diamond, an action man, a warrior, a truth-speaker and a follower of his own inexorable code of macho honor.

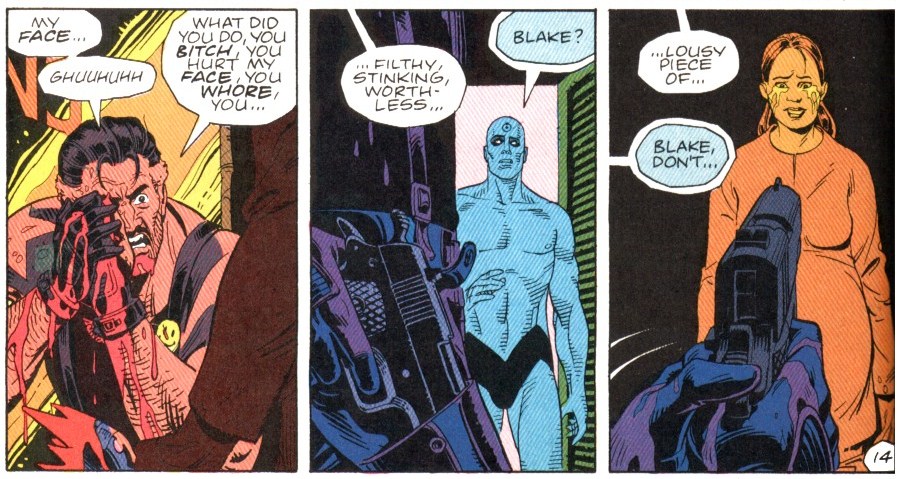

In Watchmen, Moore and Gibbons created Eddie Blake in order to completely demolish this stereotype. He is their nightmarish version of a macho antihero turned brutal misogynist/homicidal maniac. The cigar and machine gun associated with him are obvious phallic symbols, yet his phallus is emphatically used to hurt, intimidate and destroy. Moore and Gibbons went out of their way to show Eddie’s brutal misogyny in two overtly confronting scenes: the attempted rape of Sally, and the murder of a pregnant Vietnamese girl. The story is complicated by the fact that, some years later, Sally has a one-night stand with Eddie, which results in the birth of Laurie. However, this development isn’t meant to exonerate Eddie. In Sally, Moore broke new ground by using superhero comics as a medium to explore the psychology of an abused woman.[xii] For this exploration to have any credibility or substance, the following points are crucial:

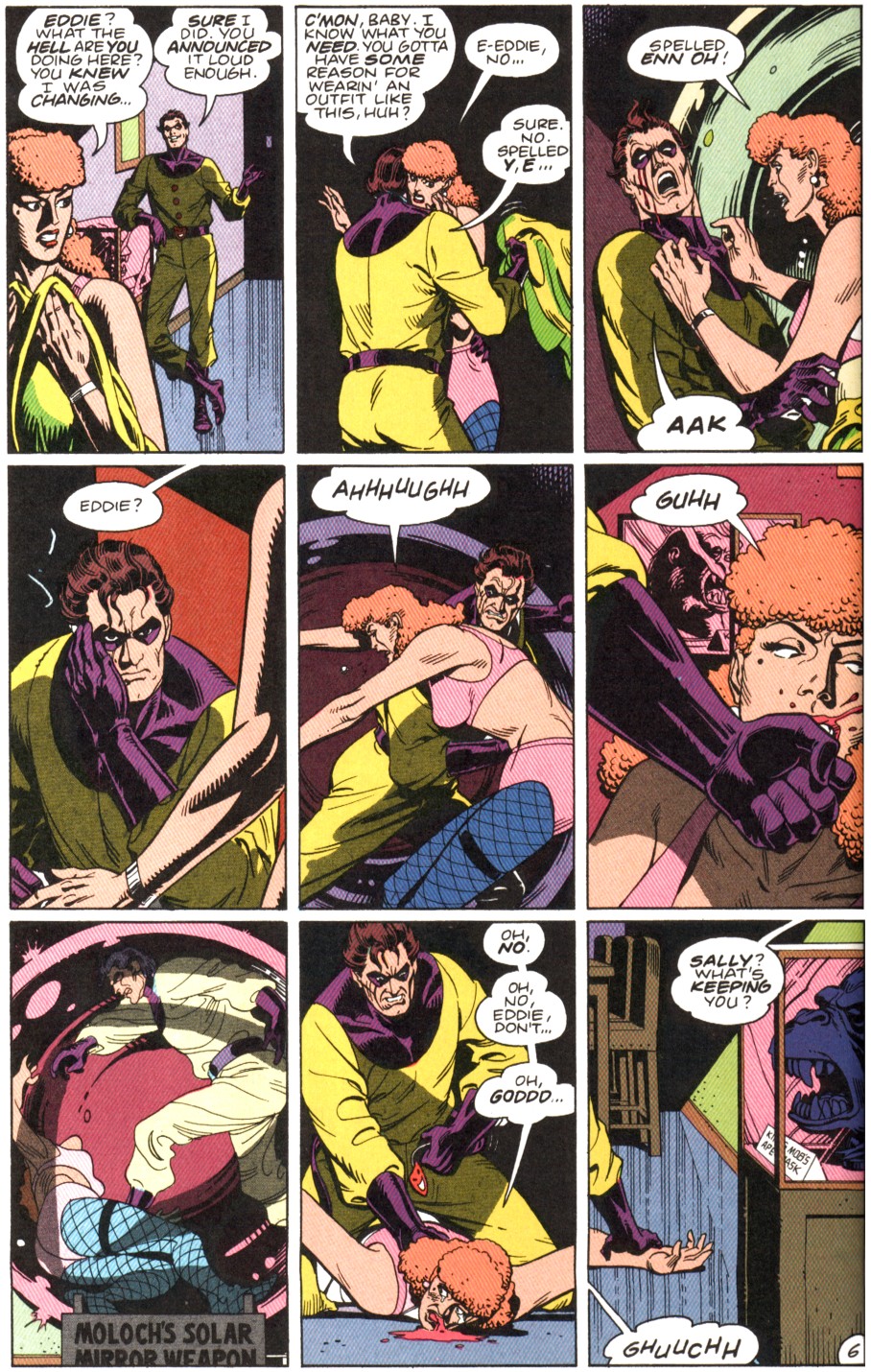

- Eddie tries to rape Sally, and the act is brutal (Figure B1). She clearly says “no”, but he still tries to rape her. As drawn by Gibbons, the violence is unflinching. We see the fear in Sally’s eyes and the blood in her mouth as Eddie punches her face and kicks her gut. Hollis describes being haunted by the memory of “bruises along [her] ribcage” (II.32). Laurie is outraged at Rorschach’s suggestion that the “alleged” rape is a “moral lapse”: “You know he broke her ribs? You know he almost choked her?” (I.21)

- Some years later, Sally sleeps with Eddie and becomes pregnant with Laurie. This episode happens off-stage. Her motivation isn’t spelt out, but in her own words: Larry was “[never] there”; she tried to be angry with Eddie but “couldn’t sustain the anger”; and he was “gentle” and “gentleness [in a guy like that] … means you reached some of that magical romance and bullshit that they promise you when you’re a kid” (IX.7).

- Their one-night-stand (“it was just an afternoon, in summer. He stopped by” [XII.29]) fills Sally with shame, confusion and self-hatred for the rest of her life. She hides the truth from Laurie because she is afraid that if Laurie finds out, she would resent and despise her.

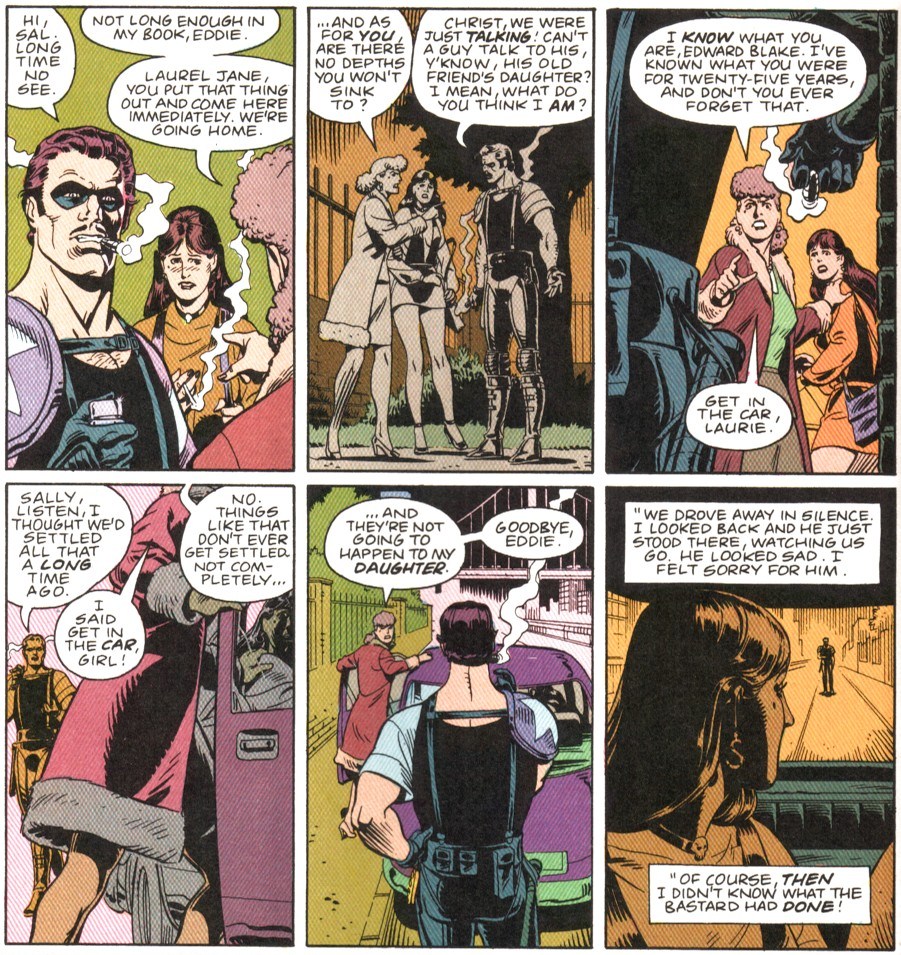

- Despite Sally’s feelings for Eddie, she wouldn’t let him anywhere near Laurie, believing he is the kind of man capable of molesting his own daughter: “I know what you are, Edward Blake. I’ve know what you were for twenty-five years, and don’t you forget that.” (Figure B2)

In short, Moore and Gibbons de-romanticized the macho antihero stereotype by insisting on the actuality and consequences of Eddie’s violence, especially the physical, emotional and psychological damages he inflicted on Sally. This doesn’t mean that they made Eddie completely unsympathetic; they just didn’t make him sympathetic on account of his aggressive masculinity. There is poignancy about a man so conscious of his guilt that he couldn’t even bring himself to confess to a priest and has to pour his heart out instead to a petty ex-criminal: “I did bad things to women. I shot kids in ‘Nam!” (II.23) There is also a touch of poetic justice to the idea that a violent misogynist should find himself yearning for the love and respect of a strong-minded daughter at the end of his life. Yet, while the book makes an effort to humanize Eddie, the last thing it offers is the luxury to admire and celebrate his aggressive masculinity.

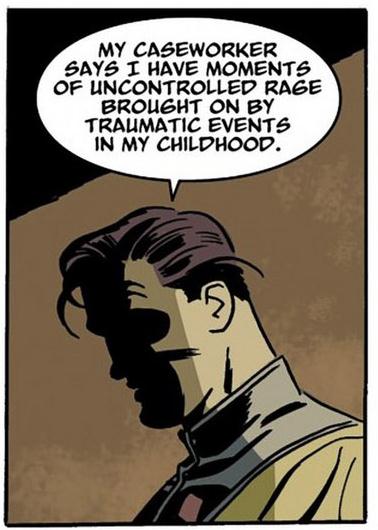

In Minutemen, Cooke throws all this out of the window and sets out to retcon Eddie into a conventional macho antihero.[xiii] Interestingly, the whitewashing of Eddie comes in tandem with the blackening of Nelson and Hooded Justice. This is noticeable already in Book 1’s introductory vignettes. Even when Eddie is about to beat someone senseless with a stick, Cooke ensures that maximum sympathy is marshalled for him by putting in his mouth an out-of-character confession that he experiences “moments of uncontrolled rage brought on by traumatic events in my childhood” (Figure B3). In contrast, the vignettes about Hooded Justice and Nelson are limited to revealing the grotesque sadism of the former (killing a man even after he has dropped to his knees begging for mercy) and the pompous vanity of the latter (taking a bath in his penthouse and bossing a manservant around).

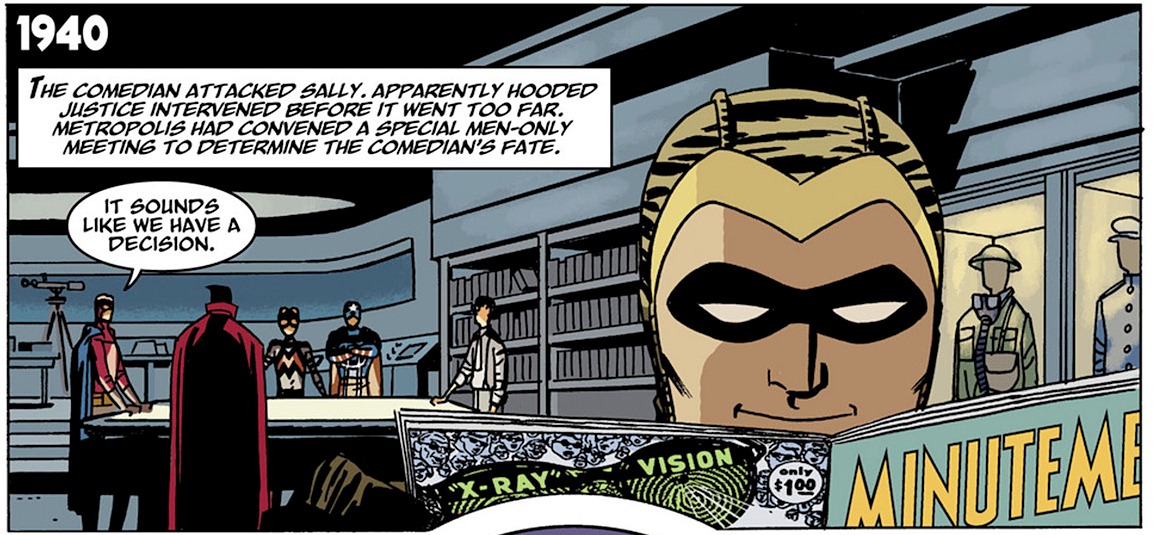

The introductory vignettes seem a minor quibble compared to what Cooke does next to exonerate Eddie: retelling the attempted rape of Sally to call into question whether it was an attempted rape. Cooke employs a number of strategies to this ends. First, he writes the victim out of the picture: no image of Sally is shown immediately before, during or after the attempted rape. In the absence of any image showing Sally’s bloody mouth, bruised body, broken ribs, or a scene showing her recuperating in hospital, the incident becomes mere hearsay, a product of Hooded Justice’s biased perception and Nelson’s prissy overreaction. Second, Cooke prefaces the Minutemen’s emergency meeting by a light-hearted image of Hollis reading a comic book (Figure B4).

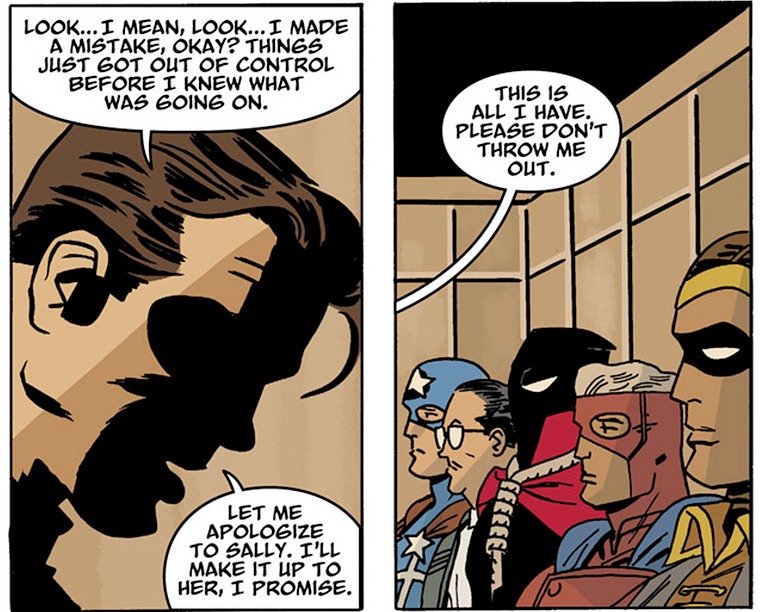

This alters the tone of the incident and supports Eddie’s claim that he is being trialled by a “kangaroo court”. Whereas Moore repeatedly called the incident “rape”, Cooke plays legal semantics with words such as “apparently” and “attacked” (at common law, Sally’s apprehension of danger is enough to make it an “assault”). Third, Eddie is no longer the cocky, unrepentant scoundrel who taunted Hooded Justice even after committing a serious crime. Instead, he is a vulnerable, confused, contrite “kid” who pleads his case poignantly with his peers: “Let me apologize to Sally. I’ll make it up to her, I promise. This is all I have. Please don’t throw me out” (Figure B5).

By omitting any visual evidence of Sally’s injury, Cooke gives weight to the theory that what happened is as Eddie says: a harmless miscommunication between him and Sally. So the emphatic “ENN OH” that Sally tells Eddie is now re-spelt “maybe”, and rape is something that a rapist can just “make up” to the victim with an apology.

The retconning goes further. When Eddie’s peers refuse to forgive him, Cooke turns the scene around to allow Eddie to become judge and jury of his peers (Figure B6).

The incident set up by Cooke in Book 1 to establish Nelson’s and Hooded Justice’s corruption now allows Eddie to turn the tables on his accusers: “We blew up a goddamn warehouse full of firecrackers and we told the world we’d saved them from Axis terrorists.” Eddie’s righteous indignation is also explicitly sexuality-based: he sees heterosexual rape as no worse than homosexuality: “You want to talk about perverts? You sick fucks are going to judge me?” Then, Cooke reverses Moore’s and Gibbons’ humiliating spectacle of Eddie being caught with his pants down by showing Eddie skilfully defeat Hooded Justice in a scuffle. While holding down Hooded, Eddie reiterates his righteous contempt for the disgusting gay men: “Stop squirming, you pansy”; “Stop right there, missy. I’ll choke your boyfriend to death”. And with a stinging anti-gay taunt: “Bunch of fags. Go fuck yourself”, Eddie exits the scene with his gun cocked and his head held high. In contrast, Nelson is left embarrassed and exposed, the panel cutting off half his face as his metaphorical hair pins fall out. In light of this, the supposedly ironic propaganda cartoon that completes the sequence—“What a man!”—can be read literally as a valorization of Eddie’s gutsy exposure of his teammates’ hypocrisy.

Cooke further consolidates the theory that the rape is “legitimate” in his depiction of Eddie’s reunion with Sally in Book 4. In the original Watchmen, Sally describes their reunion like this: “I shouted at him. He looked surprised, couldn’t image why I’d bear a grudge …. I just couldn’t sustain it, the anger” (IX.7). This suggests among other things that Eddie is a man so morally deficient that he felt no qualms about casually dropping by to woo a woman he has bashed and tried to rape. Instead, Cooke whitewashes their reunion by placing them in a completely honorable setting: at the graveside of the martyred Ursula. Dressed in a nice clean suit to pay his respects to his fallen comrade (those “bunch of fags” Nelson and Hooded are the only ones who didn’t show up), Eddie indeed “ma[kes] it up” to Sally. He taps her gently on the shoulder. She, not he, looks “surprised”. There is no shouting, no attempt to sustain her anger, and her uneasiness is easily quelled by his manly reassurance of his good will. Cooke then treats us to an extended flashback to Eddie’s participation in the Pacific War, which becomes a retcon version of the later Eddie in Vietnam.

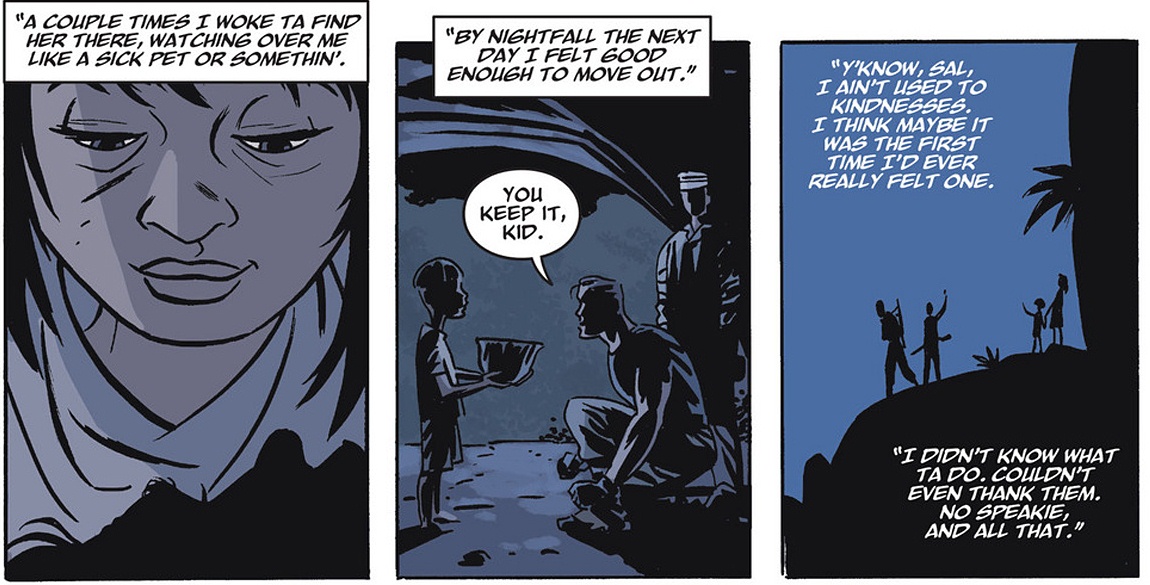

In contrast to Moore’s hyper-masculine psychopath who found his true element in the killing fields of wars, Cooke’s Eddie is portrayed as an innocent soldier poignantly losing his innocence in a contrived scenario worthy of any military tearjerkers. Injured on the battlefield, Eddie was rescued by a kind-hearted Solomon woman and her little boy (Figure B7).

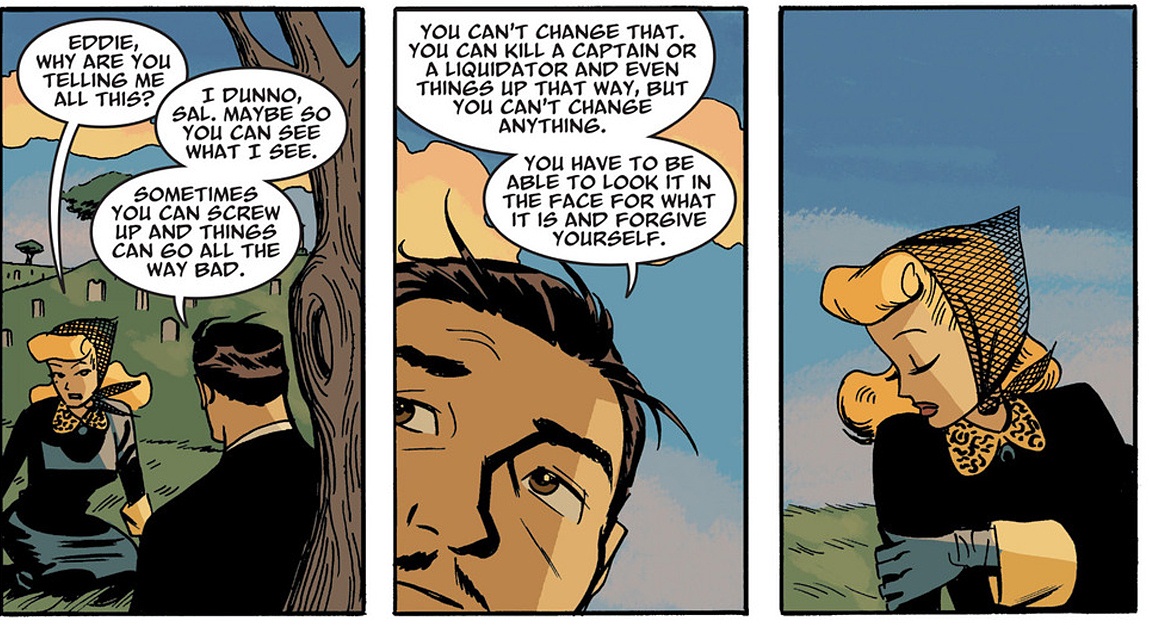

Despite their cultural and linguistic differences, he bonded with the pair because this was the first time anyone had treated him with kindness. He was devastated when his nasty commander gave orders to bomb the natives’ village and he could do nothing to save their lives. So, Eddie once again learned that life is a bitch and one must play hard to survive: he killed the nasty commander that killed the woman and boy. Apparently, the war also brought out something of the poet-philosopher in the uncouth Eddie, and he teaches Sal a lesson from the school of hard-knocks: “You have to be able to look it in the face for what it is and forgive yourself.” (Figure B8)

Sally reacts by looking away demurely like a little girl, acknowledging the potency of Eddie’s manly eloquence. So Moore’s and Gibbons’ morally bankrupt aggressor has morphed into a salt-of-the-earth gentle giant spouting pearls of wisdom to purify a woman’s soul. Presumably, the shooting of the pregnant Vietnamese woman thing (Figure B9) is just an isolated incident that happens along with all the other shits that happen by the time Eddie gets to ‘Nam.

And because Eddie is such a rough diamond, macho badass and poet-philosopher, Sally naturally falls in love with him and offers him her body and soul. Their reunion is no longer “just an afternoon, in summer. He stopped by. I tried to be angry …. I just felt ashamed” (XII.29). It is now retconned into a serious relationship which she wholeheartedly embraces and passionately enjoys. In contrast to Dr Manhattan’s epiphany that Sally “loves a man she has reasons to hate” (IX.26), Cooke’s version of Sally really has no reasons to hate Eddie except that their consensual relationship didn’t work out the way she wanted. So, trauma, anger, shame, guilt and emotional dependency which are the complex symptoms of an abuse victim are reduced to stereotypical female neurosis and jealousy that Eddie is just too much of a stud to settle down with her. And what Moore and Gibbons had the good sense to leave out, Cooke exhibits in full chauvinistic detail: he not only depicts Laurie’s conception as the result of a quick shag between Eddie and Sally in the lavatory on Sally’s wedding day, he also depicts it as a facetious homage to the famous Tijuana bible image in the original Watchmen (Figures B10-11).

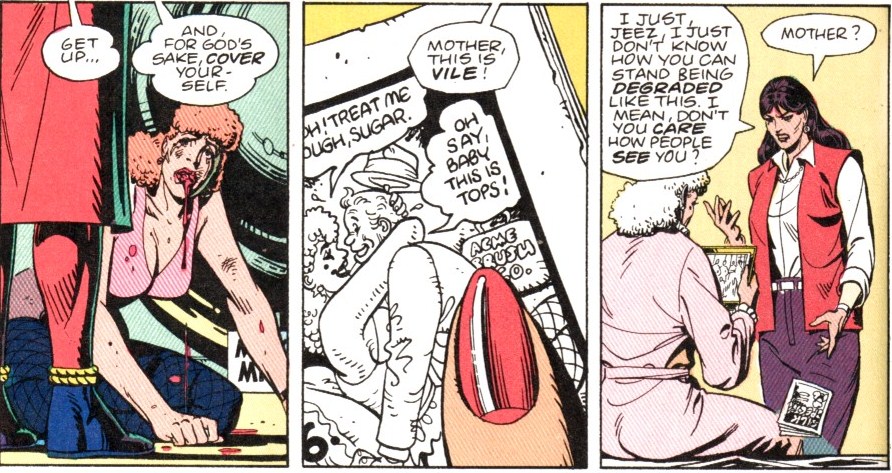

The contrast in concept and execution is stark. In Moore’s and Gibbons’ depiction, the three panel sequence offers an incisive critique of gender violence in comics:

- Panel 1: A confronting image of sexualized violence is presented. Sally is on her hands and knees, spewing blood while exposing her cleavage to the readers. Sally’s “rescuer” Hooded Justice stands over her. He is unsympathetic to her plight and tells her to cover up, insinuating that she is partly to blame for Eddie’s violation of her.

- Panel 2: The scene abruptly changes to a page from a Tijuana bible. The crudely drawn porno cartoon reiterates the misogynistic stereotype that women invite rape and enjoy “rough” sex. But the comic-within-a comic device makes the readers self-conscious that they are reading a comic book, and reminds them of the genre’s tendency to eroticize sexual violence. Covering the most explicit part of the porno cartoon and frustrating the (male) readers’ gaze is a woman’s red-varnished fingernail and the libido-dampening caption: “Mother, this is vile!”

- Panel 3: The image zooms out and we see that the speaker is Laurie, who tosses the porno comic aside in disgust and scolds Sally for accepting this kind of degrading treatment of women. The comic book tradition of eroticizing sexual violence is undercut by a woman’s angry, accusatory voice.

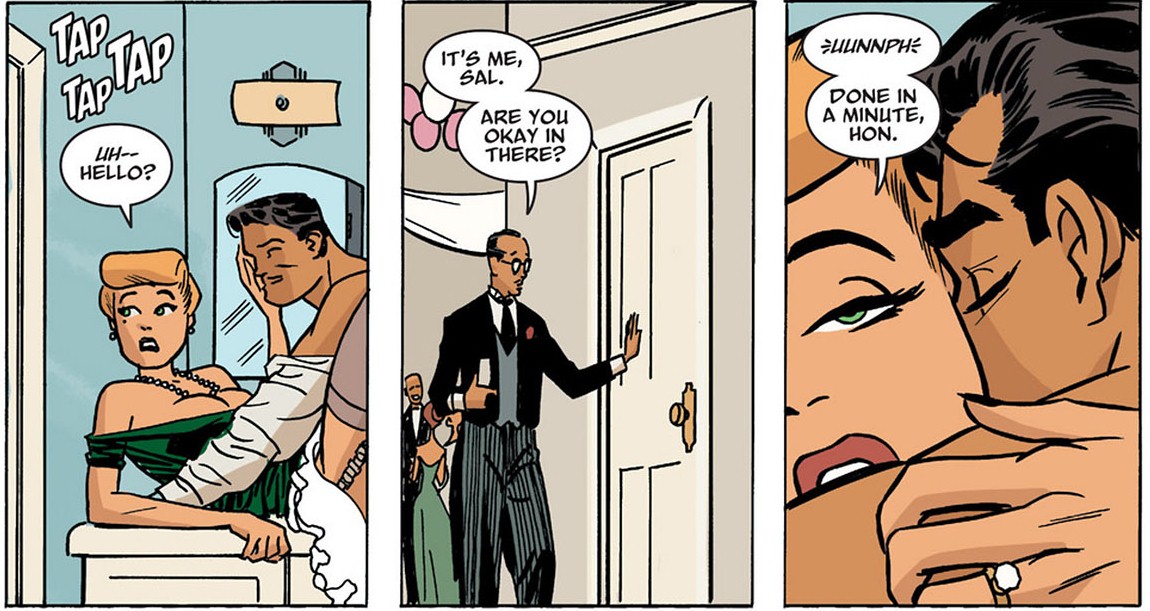

In Cooke’s depiction, the three panel sequence is all about celebrating male sexual conquests and boosting male ego, and would not be out of place in any seedy frat boy sex comedy:

- Panel 1: A tawdry image of frivolous sex is presented. Eddie is seen screwing Sally in the lavatory. Good old Eddie has finally vindicated his manhood by knocking up the girl who thought she could say “no” to him.

- Panel 2: Larry Schexnayder, the bumbling beta male, anxiously asks his bride why she is taking so long. He is stupidly imperceptive that he has been cuckolded by a real man.

- Panel 3: The image zooms in on Sally’s face. With a dazed expression, she fobs off Larry while enjoying being banged by Eddie. Significantly, the readers’ perspective corresponds to Eddie’s: they are positioned as Eddie giving it to Sally. Her line “Done in a minute” is sexually suggestive and anticipates the come-shot that happens off panel.

Thus a subtle, incisive critique of sexual violence is transformed into a moment of adolescent toilet humor and phallocentric double entendre in complete support of Eddie’s virility. This more or less summarizes the tenor of all six books of Minutemen. Cooke has ensured that just about anything Eddie does is given an explicit or implicit justification. Even the “twist” in Book 6, if one thinks about it, is really all about setting up a big finish to demonstrate what a cool badass Eddie is. In the original, Eddie’s suspected part in the murder of Hooded Justice was part and parcel of his nasty, vicious personality. Hooded Justice was completely right to interrupt the attempted rape, yet Eddie not only wouldn’t admit that rape is wrong but also wouldn’t allow the perceived blemish to his manhood to go unrevenged. And rather than confronting Hooded upfront, he likely resorted to a secret assassination: a bullet to the head, J.F.K.-style.[xiv]

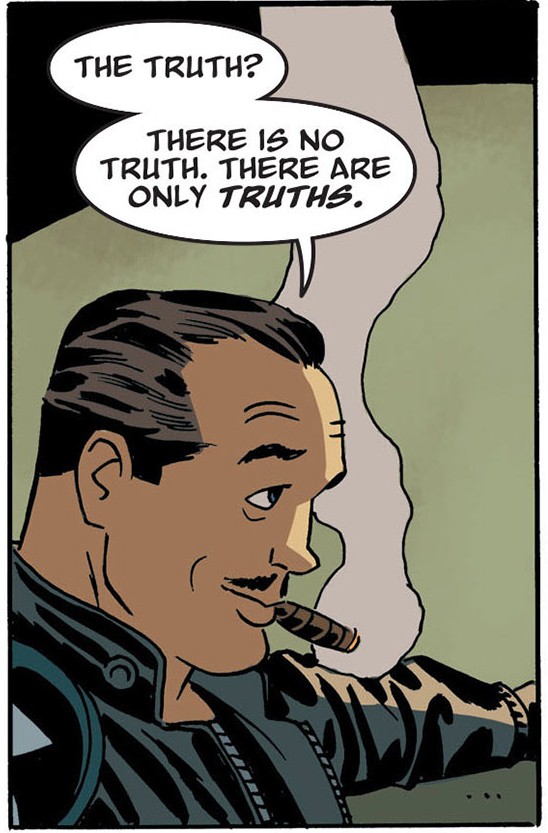

In Cooke’s version, everything comes together to vindicate Eddie. Hooded Justice is a sick bastard who is far sicker than Eddie. Eddie can effortlessly defeat him in head-to-head combat. Eddie’s “attack” on Sally is a harmless misunderstanding rather than a brutal rape attempt. Sally’s reunion with Eddie is a heart-warming romance rather than evidence of her vulnerability, confusion and psychological damage. And Eddie doesn’t even want to kill Hooded—he only wishes to “humiliate” him. The killer turns out to be the unwitting Hollis Mason, who publishes a sanitized version of Under the Hood as a cover to “protect” himself and those dearest to him.[xv] Eddie retains the ability to outsmart and outplay everyone even as his moral culpability is drastically reduced. His sage advice to Hollis: “there are only truths” (Figure B12) becomes the de facto “vision” of the series: it takes a real man to make lesser men see what they don’t want to see.

Eddie is now a macho antihero akin to Frank Miller’s version of Batman, a master tactician who follows his own code of morality and dispenses his own brand of badass justice, a man whose heroism lies in his manly indifference as to whether the world sees him as a hero. Moore and Gibbons’ deconstruction of a macho antihero has been fully reconstructed by Cooke into a traditional macho antihero.

[i] Some critics (e.g. Hughes) have accused Moore of hypocrisy for wanting to stop other people from revisiting Watchmen when so many of his own books are based on other people’s works. While I don’t have any strong objections to the idea of the Watchmen prequels per se, I don’t think the charge of hypocrisy against Moore is really tenable. There is surely a big difference between a writer borrowing elements from public domain classics to create original fictions in a different medium and a large corporation wielding copyright laws to develop a franchise explicitly marketed as being continuous with the most celebrated work of a disenfranchised writer.

[ii] As of 19 May 2013, Minutemen and Silk Spectre are the most favourably reviewed Before Watchmen titles on Comic Book Roundup: Minutemen scores 8.4; Silk Spectre scores 7.9. Scores for the other books are: Dr Manhattan 7.9; Ozymandias 7.0; Rorschach 6.9; Nite Owl 6.1; Moloch 5.7; Comedian 5.4; Dollar Bill 5.3.

[iii] E.g. MTV Geek: [Minutemen] honestly felt like a book I’ll be able to put on my shelf right next to Watchmen. It’s not the original work, but it’s also not, like everyone feared, detracting from Moore and Gibbons’ book… It’s enhancing it” (Zalben); Newsarama: “For the first time since reading the Before Watchmen prequels, I feel like the authors have actually added something to Alan Moore’s seminal work” (Pepose par.1); Superherohype: “Cooke has created back stories that not only don’t negate the original text but make it richer” (Perry, Minutemen par.4); “What [Cooke and Conner] have created is a good story that not only fits well into the Watchmen mythos, but could be removed from the lens of Watchmen and would still hold up” (Perry, Silk Spectre par.2).

[iv] See, e.g. Moore’s interview with Pindling: “I wanted to … make [Rorschach] as like, ‘this is what Batman would be in the real world’. But I have forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans, ‘smelling’, ‘not having a girlfriend’, these are actually kind of heroic! So Rorschach became the most popular character in Watchmen. I made him to be a bad example. But I have people come up to me in the street and saying: ‘I AM Rorschach. That is MY story’. And I’d be thinking: ‘Yeah, great. Could you just, like, keep away from me, never come anywhere near me again as long as I live?’” (4.42-5.28).

[v] For an essay propounding the ingenious theory that these diners are actually Hooded Justice and Captain Metropolis, see Gifford.

[vi] This overarching vision is expressed by Jon in his conversation with Laurie on Mars. At this epiphanic moment, the most powerful being in the universe is humbled by the realization that the existence of human lives is already a “thermodynamic miracle”; a person doesn’t need to be a “hero” to be important. Something of this vision is also expressed by V in V for Vendetta: “Everybody is special. Everybody. Everybody is a hero, a loner, a fool, a villain, everybody. Everybody has their story to tell” (Chp 3).

[vii] In Watchmen, Hooded Justice is said to harbor neo-Nazi sympathies (II.30) and has roughed up several of his former boyfriends (IX.31). Nelson has made racist remarks about African and Hispanic Americans (II.30), and his ulterior motive in forming the Minutemen is explored in Dan Greenberg’s and Ray Winniger’s non-canonical role-playing games (see Callahan). Yet, even with these precedents in mind, Cooke’s portrayal still comes across as relentless in its negativity. Cooke isn’t the only Before Watchmen writer to try to hetero-normalize the Watchmen universe. In Len Wein’s Ozymandias, the “possibl[y] homosexual” Adrian Veidt is also “outed” as a heterosexual.

[viii] I suspect Cooke might plead that Bill’s attitude is “historically accurate” here (to make a Mad Men analogy: Don Draper is sexist, but that doesn’t make Matthew Weiner so), but the tenor of Cooke’s writing goes beyond historical accuracy. On Bill’s death, Hollis is unreserved about Bill’s integrity: “Bill was a good man and a good friend. I miss him.” (IV.5) The problem is that Cooke has done nothing in all six books to establish Bill’s goodness and friendliness except through his male-bonding scenes with Eddie and Hollis over their righteous disgust at Nelson and Hooded. This makes it hard not to infer that Bill’s homophobia is presented as being completely consistent with his goodness and friendliness.

[ix] The Bluecoat and Scout sequence is a good example of Cooke’s inability to transcend banal heroic antics even in a moment that is supposed to offer meaningful historical insights. The duo is obviously Cooke‘s attempt to comment on US treatment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. However, the duo comes across not as real people but as moralistic tools. If we compare Cooke’s cloyingly sanctimonious Scout to Moore’s refreshingly normal African-American boy Bernie, who doesn’t need to do anything heroic to convince us of his humanity and make us think deeply about the cultural construction of heroism—Bernie’s position as reader of the Tales of the Black Freighter makes him an “everyman” reader of Ur-heroic narratives—we have a decisive demonstration of what makes Cooke a mediocre writer and Moore a great one.

[x] Cooke’s moralistic pitting of the “best buddies” Hollis-Byron against the “degenerate lovers” Nelson-Hooded establishes a good-vs-bad dichotomy that the original Watchmen doesn’t support. In the reunion party at Sally’s house in Book IX, Nelson’s words clearly indicate that he has kept in touch with the mentally ill Byron: “I’d better go check outside. He should arrive soon, and I promised I’d meet him ….” (IX.11)

[xi] E.g. in the Sin City story “The Hard Goodbye”, Marv chivalrically knocks Wendy out to spare her witnessing his brutal revenge on Kevin. Rape as an act of honor is probably less common in mainstream US comics than in Japanese manga. E.g. in Kazuo Koike’s and Ryoichi Ikegami’s outrageously compelling The Injured Man (Kizuoibito), the alpha male hero’s violent sexual antics (which include the rape of a young teenage girl) are presented as unambiguously heroic. Moore’s essay “Invisible Girls and Phantom Ladies” demonstrates that he is well aware of the problems with the genre’s depiction of women.

[xii] Moore is unequivocal about this point: “He raped her. He raped her and she still had Laurie with him some years later … she had consensual sex with him some years later. And I was trying to think, is this psychologically credible? And I could see that it was—I certainly didn’t want to say: ‘Ah, she secretly enjoyed being raped,’ or something like that. But I wanted to say that it might be more complex than that …. That there might have been, despite his behavior, there might have been some part of her that responded or that she felt guilty about the response…. I’m not saying that it makes it right for him to do those things or that she is right to return to an abusive partner; but I’m saying that it happens, that it’s a real part of how humans fit together” (Khoury 117-118).

[xiii] On the whole, the portrayal of Eddie is so favorable in the franchise that one wonders if DC had given an editorial mandate to redeem his character. The whitewashing is equally evident in Brian Azzarello’s six-issue Comedian, which elevates Eddie almost to a symbol of America’s troubled conscience by charting his Kurtzian descent into the heart of darkness. Significantly, none of the books mentions the rape of Sally or the murder of the Vietnamese woman—surely a glaring omission considering that Eddie’s yearning for Laurie is psychologically explainable as an outcome of his guilt about murdering his unborn child in Vietnam. In the original, Laurie’s throwing a glass of scotch into his face (IX.21) mirrors the Vietnamese girl cutting his face with glass (II.14).

[xiv] This point is offered as a speculation rather than as a fact in Watchmen. It is based on four pieces of information: (i) Eddie warns Hooded before he leaves: “I got your number … [O]ne of these days, the joke’s gonna be on you’ (II.7); (ii) Hollis conjectures that Hooded Justice’s real identity is circus strongman Rolf Müller, whose “badly decomposed body” was found “shot through the head” (III.30); (iii) Adrian asks: “Had Blake found Hooded Justice, killed him, reporting failure? I can prove nothing” (XI.18); (iv) at the white house cocktail party, Eddie jokes: “Just don’t ask where I was when I heard about J.F.K.” (IX.20)

[xv] I have trouble following Cooke’s reasoning in this episode. The facts are simple enough: Eddie wants to get back at Hooded Justice. He disguises himself as Hooded and tricks Hollis into believing that Hooded is the paedophile Ursula was looking for. This leads Hollis to hunt down the real Hooded and kill him in a scuffle. Years later, Hollis prepares to tell all in his book Under the Hood. Before the book’s publication, he receives a midnight visit from Eddie. Eddie shocks him with an account of what really happened, and advises him that “Mr Hoover and other interested parties” would prefer a “light-hearted”, “sunny reminiscence” of the truth. Out of a desire to “protect” his friends, Hollis agrees to rewrite the book, and the version of the book excerpted in Watchmen is a “sanitized” account of the truth. I have at least two problems with this revisionist history: (i) I fail to see how the pages from Under the Hood as they appear in Watchmen would have been acceptable to “Mr Hoover and other interested parties,” given Hollis’ explicit critique of the government’s role in manipulating the phenomenon of the masked avengers; (ii) given that Cooke has already established in Book 5 that Sally is strongly against the publication of Under the Hood (Moore’s Sally also angrily reprimands Hollis for mentioning the book to Laurie at the reunion party in Book IX.12), why doesn’t Hollis “protect” Sally’s privacy by censoring the parts relating to her? If the “truth” was as Cooke had painted them, I suggest the most plausible and sensible action for Hollis would have been to abandon publishing Under the Hood altogether. My impression is that Cooke is so determined to create a cool “gotcha” moment for badass Eddie that he is willing to ride roughshod over realism, plot logic and character consistency in order to achieve this sensational effect.

Holy shit this looks despicable.

Comics critics have once again exceed their quota for imbecility in praising this sorry excuse for toilet paper. And what colossal fool thought Cooke was such a great writer that he needed to do two books.

This is a great article, I will look forward to part 2. However, as you say, Moore made a point to call the crime “rape” throughout, and since the original comic shows rape occurring without ever saying that the act was anything less, I see zero reason to call it “attempted.” Oh, but wait for it….

I have to admit, this appears to be worse even than I thought it could possibly be. Anybody who thought Alan Moore was overreacting owes him an apology, it looks like.

Owen beat me to it – incredible article. I’d avoided most mention of this series so far, but this is so much worse than I thought. Looking forward to the second part!

James, there is evidence in Watchmen that the rape was attempted, not completed. This doesn’t make Blake any less of a monster, nor is the evidence incontrovertible. It does exist, though.

LAURIE: BLAKE WAS A BASTARD. HE WAS A MONSTER.Y’KNOW HE TRIED TO RAPE MY MOTHER BACK WHEN THEY WERE BOTH MINUTEMEN ? (this is in Watchmen #1)

Sally could have covered up the horrible truth to Laurie, obviously, or Laurie could be soft-pedalling it herself here for her own reasons… but the notion that there is no reason to call the rape “attempted” is simply not true.

Again, Blake is scum…his intent was obviously to rape Sally and whether he did so or not doesn’t change this. Certainly, any attempt to resuscitate him as a “hero” of some kind is totally against the purposes of Watchmen itself.

I’m sure I’ll be morally censured for pointing this out, but whatever. I’m not going to respond.

I can’t imagine it would even make any difference at law, would it? If Laurie’s right, he beat her mom bloody and only failed to rape her because he was physically prevented.

And that’s not even discussing the fact that he murders the mother of his child in cold blood….

The effort to ret-con him into a heroic figure is insane.

Okay—but you gave a good explanation of why Laurie would mistaken to think that and the scene itself is shown in a way that indicates otherwise. In a court of law, an equivalent real incident witnessed to that explicit degree should certainly lead to the assailant being jailed for sexual assault and I believe, for rape as well. Any “between the panels” ambiguity could simply be seen as that the sequence is part of a DC comic that isn’t allowed to show penetration. I have been over this particular route before, arguing with the same people who also don’t see what happens to Maggie’s little brother in Love and Rockets #4 as rape either. Those same commenters are consistent in their refusal to acknowledge these types of scenes and now I am disappointed that this otherwise good article seems to have the same problem, of lessening the impact of a powerful and horrendous attack.

I don’t want to necessarily get side-tracked on this if we can avoid it; so since both sides have made their points, I’m hoping we can keep focused on Wiliam’s article?

Oh, and I see in footnote #xii that Moore himself absolutely intended the scene to represent a rape. Take that, mitigators. Comics are not generally a place where explicit images are permitted, but anything other than the most explicit image won’t play, apparently, because there is always someone who will refuse to see what they have decided isn’t there.

Genuinely excellent article. I like the fact that the author refuses to address the vexed question as to whether ‘Before Watchmen’ should have occured at all, which clouds any evaluation of the work itself.

I might dissent a bit about the homophobia ascribed to the depictions of Hood Justice and of Captain Metropolis. In Moore’s original, the two were depicted as despicable individuals already.

And the Ursula-in-church scene is indeed heavy-handed and hokey, but it essentially expresses a loss of faith in God, not an affirmation of it.

Hollis the killer? Spits in the face of Moore’s intent!

Dollar Bill’s intolerance isn’t condoned, though. He comes across as an absolute asshole.

Still — congratulations, and I look forward to Part 2.

PS– in interviews, Moore has always said that Eddie raped Sally. He should know.

I don’t think HJ and Captain Metropolis were depicted as despicable. Neither of them gets a ton of screen time; HJ comes across as violent and not especially sympathetic, and CM is portrayed as nostalgic and sort of ridiculous. But…they’re certainly not anywhere near as morally repulsive as Rorschach or the Comedian or Veidt.

I didn’t manage to finish the article, let alone read the comments. But boy did you convince me to never, ever even think about reading this shit. Oh, I also love your discussion of Watchmen at the beginning and really really love the Alan Moore quote about people who like Rorschach.

The Darwyn Cooke Minutemen was the only one of these books I might have given a glance. I don’t need to see any more of it. What a disgrace.

As for this “Was it a rape, or was it an attempted rape?” tangent, I don’t know why it makes any difference in a reader’s view of Blake. He’s no less repugnant in either reading.

What gets people defensive is being attacked for being immoral for taking the view that the assault was an attempted rape. Eric appears to be tired of it, and so am I.

The book supports the attempted rape interpretation all the way through. Every reference to it outside the flashback scene describes it as such. As for the scene itself, the pacing points to the attempted rape interpretation, as does the use of tropes. A key aspect of Moore and Gibbons’ storytelling strategy is that when they shift to tropes to make story points, the cliché reading of the tropes is always proven to be wrong by the greater context.

To the best of my knowledge, Moore and Gibbons have consistently stated since the project began publication that they were given complete editorial freedom and that DC respected this entirely.

Assertions that DC would have been too uptight to have published the book if it featured an actual rape are quite inaccurate. Watchmen was published by DC during the Dick Giordano editorial era, which was notoriously licentious. Some examples: Camelot 3000, in which the medieval Sir Tristan is shown raping Mordred’s nanny; Chaykin’s Blackhawk, which included a blowjob scene; and The Sandman #6, in which a woman gives an explicit account of having sex with a cadaver. Speaking of necrophilia, there was also this, and on the cover no less. As for Moore’s efforts, you have, among other things, Batman: The Killing Joke and Swamp Thing #29. I hope it’s safe to assume those are well-known enough that I don’t have to take the time to describe them. There’s also Mike Grell’s Green Arrow comics, and plenty more besides.

The cited interview in which Moore refers to the assault as a rape was conducted in 2003, a good 17 years after he scripted the scene. It’s more than possible that his memory is playing tricks on him. This interview, published a few months after the book was completed, has Gibbons describe the attack as an attempted rape. Gibbons also does so in Moore’s presence, and Moore does not contradict him. Make of that what one will.

I don’t know if, as Alex says, Moore has repeatedly stated that Blake raped Sally in interviews. But Eric is the editor of a fairly comprehensive collection of Moore interviews from an academic press, so if anyone can confirm or dispute that point, I think it’s him.

It seems possible that Moore might consider it a rape even if it was interrupted. Which seems like it would be an entirely reasonable stance to take.

Fucking brilliant analysis. Thanks!

I think it is too easy to be led astray by Cooke’s art, which I admittedly love, but even that in Minutemen suffers from too obvious an effort to structurally echo Gibbons without sufficient thought to what it actually accomplishes for the narrative.

Looking forward to Part Two.

Noah–

No argument there.

I enjoy Cooke’s art too…though with something like this, you start moving into the area where the fact that he’s competent and talented actually starts to make the thing more evil.

For instance, that lesbian erotica scene up there is entirely competent lesbian erotica. But that just makes it more nauseating in the context of the homophobic themes in the book, and of the serious effort to deal with sexual exploitation and violence in the Moore/Gibbons original.

Also, if he was purely a hack, no one would take this seriously for a second. The fact that he can draw is the whole reason anyone pretends he can write, it seems like.

Minutemen and Silk Spectre were the only two titles of this series I picked up on the strength of my enjoyment of Cooke’s work – but never finished either one of them.

It became pretty clear pretty quickly that the comic industry never learns the right lessons from works like Watchmen. It is clear that Cooke _thinks_ he is doing something noble with his work here and his handling of Silhouette, but ultimately that desire to be noble leads the work into the dangerously romanticized representation of heteronormative heroism that the original work critiqued.

Pretty sure there will be an “After Watchmen,” which no doubt will be even worse.

Brilliant. Too bad you had to read the damn things to write this, but it was well worth it (for the rest of us, anyway).

Some of your readings do seem like special pleading — like when Moore portrays non-hets in a negative way, it’s evidence of his deep understanding of humanity, but when Cooke does it, it’s sign that he’s a homophobic dickhead; or similarly when Moore gives the Comedian some sympathetic traits, vs when Cooke does — but I imagine it wouldn’t seem like that if I’d read the actual “product” in question, so I defer to anyone with a strong enough stomach to read it.

It’s interesting that DC went with prequels rather than sequels — the former, at least to my mind, undermine the integrity of the original work much more than the latter would — but I suppose sequels are hard when the kewlest characters are dead at the end of the book. I thought for sure that Doc Manhattan would somehow use his powers to alter history so that everyone — above all, Rorschach — would be alive and ready for crossover into the main DC universe, but this doesn’t seem to have happened. Maybe in the sequel.

The most depressing part of fan reaction is just how unselfconsciously so many reviewers,”journalists”, and other sycophants started using phrases like “the property” or “the Watchmen universe” or “Watchmen lore”. Gross.

To put those ratings into perspective, have you looked at other ratings on that metacritic-ish site? Comics reviewers have pretty low standards in general…

Okay, I tracked down Gifford’s essay and I have to say, that as a Watchmen fanboy, I really, really like this idea.

>>I imagine it wouldn’t seem like that if I’d read the actual “product” in question, so I defer to anyone with a strong enough stomach to read it.

Actually, at least one of his complaints is so unsupportable when given its full context that it stinks of knowing intellectual dishonesty: Eddie’s intro scene, which Leung describes “Even when Eddie is about to beat someone senseless with a stick, Cooke ensures that maximum sympathy is marshalled for him by putting in his mouth an out-of-character confession that he experiences ‘moments of uncontrolled rage brought on by traumatic events in my childhood'”

Here’s the full scene in question: http://imgur.com/5BO1X0q

The line isn’t an “out of character confession”, it’s a sick joke! This is an excellent characterizing moment, which establishes both that the Comedian is knowingly evil (not typically considered a sympathetic trait), and his cynical viewpoint towards ‘the system’ of psychology/social services. (If the concern was posting too much of the comic for review purposes, well, that’s no excuse. Here it is at a tighter view that still preserves intent: http://imgur.com/mW5Vx6Q)

I haven’t read the remainder of the comic, but if Leung feels the need to tight-crop that single line, taking it out of context and bending it against its clear intent in order to promote his arguments, it does not bode well for the relevance and accuracy of the rest of his review.

Thanks everyone for your comments. irrelevant: By “out of character”, I meant that the line doesn’t sound like a sentence that Eddie’s character would say at that particular moment. It is entirely believable that Eddie would have had a traumatic childhood, but it is unnatural for Eddie to explain himself by quoting his psychologist/sociologist’s diagnosis verbatim. I don’t agree that the line is a “sick joke”; Cooke’s drawing of Eddie in a shadowy profile with his chin down suggests that it is a moment of serious insights into Eddie’s character. My point is that this jarring device reveals Cooke’s determination to put in a good word for Eddie even when he is committing violence.

If you compare Eddie’s intro with Hooded Justice’s intro, you’d see that the approach is completely different. HJ probably has had just as rough a childhood as Eddie, but you don’t get any heart-felt confessions from him. In fact, Cooke made the HJ scene much more lurid than the original. In “Under the Hood”, Hollis said that HJ beat three bank robbers/would-be rapists “with such savagery that all three required hospital treatment and … one subsequently lost the use of both legs”. A violent act admittedly, but no life was lost. In Cooke, the scene is rewritten into a horror freak show. The robbers walk into an empty factory. One by one they disappear after howls of screaming. The last robber sees HJ approach and drops to his knees begging for mercy. He is then thrown out of the window, crashing into the cars and dying instantly. A cop who saw the mangled body was so traumatized he quit the force.

Eddie gets to tell us that he’s had a “traumatic childhood”; HJ is just evil incarnate.

As I say in the article, the vignettes are only a “minor quibble”. The worst of Cooke’s revisionism doesn’t happen until later, so if this scene is your only complaint, I’m happy to concede your point. Now if someone can explain to me how Cooke’s handling of the rape of Sally and the rewriting of the Eddie/Sally reunion into a beautiful romance is consistent with “Watchmen”, I’m all ears. From where I stand, it is whitewashing, pure and simple.

That moment of introspection (figure B3) seems like your typical action movie pause before violence. Putting aside spatial considerations, it would have been better served by its positioning at the bottom of the page with the next page being a *really* violent reaction. You get that in Tarantino movies as well but the evil dude tends to go on at some length and more eloquently.

It fails utterly as a “sick joke” because it’s so predictably and clumsily done. Like some cut rate TV superhero series (with stock villain) and most scenes in the horrible New Frontier comic. No wonder the Eisner judges gave the Eisner nomination to Hawkeye and not this.

There seem to be a lot of comments praising Cooke’s art but it seems totally unsuited to the material. The baseball bat bashing scene looks like something out of Bugs Bunny.

I don’t know, am I the only one who sees that scene of the Comedian robbing the bar as more than a little on the nose? I think this is where that criticism of Cooke being “literal-minded” comes in. Granted, Eddie Blake is a vile character, and I get that he’s young here, but unless there’s yet more context to this (which I have zero intention of finding out for myself), it seems inappropriate to have him antagonising a random barkeep this way and engaging in petty theft – outright criminality towards an American civilian. Part of the point of Eddie Blake was the fact that his malevolent predilections are used in the service of “good.” whether as part of the Minute Men or as a “war hero” in Vietnam. He’s like a twisted Ancient Greek hero or Nietzschean “beast of prey” who thrives in situations of lawlessness in which he gets to impose law with extreme prejudice. I’m pretty sure it was very deliberate the line Alan Moore was walking when writing the character that was obvious enough to begin with.

An obvious point of comparison to this scene (and the reason it even exists) is the young Comedian’s sexual assault of Sally Jupiter. But of course, they are very different scenarios, not least because the latter spins out into a very complicated and central issue in the original comic. This bar scene is like an ill-advised attempt to reverse-engineer the Comedian’s character in general and perhaps that rape scene in particular to illustrate that, “See you guys, the Comedian is a really bad guy.” It’s ham-fisted and hackneyed, like explaining a punchline to a really good joke really badly.

As I see it, any way one reads the scene it just doesn’t work.

” Part of the point of Eddie Blake was the fact that his malevolent predilections are used in the service of “good.”

Eh, Comedian’s backstory on that page kind of reminds me of The Godfather. Wasn’t the protagonist in The Godfather back from serving in the army or something?

It’s not crazy to link America’s love with romantic gangsters with america’s love for patriotic violence. Not that Cooke seems capable of exploring the theme, mind you.

>>By “out of character”, I meant that the line doesn’t sound like a sentence that Eddie’s character would say at that particular moment.

But it’s exactly what he’d say if he’s a smirking thug. Heck, note Ng’s criticism: the joke didn’t work for him because it’s too predictable!

>>It is entirely believable that Eddie would have had a traumatic childhood… Cooke’s drawing of Eddie in a shadowy profile with his chin down suggests that it is a moment of serious insights into Eddie’s character.

The line doesn’t hinge on whether Eddie had a disturbed childhood, or has an actual caseworker or not, it hinges on the fact that he gives a “serious” answer to a rhetorical question, and then follows it up with an action that contradicts that supposed sincerity.

Essentially, this comes down to how you read the tone of the scene. You can read it in a way that is consistent with –and perhaps a bit much on the nose for– “The Comedian,” as a setup -> punchline structure. Or, you can instead try to read it as a confusing and completely dissonant attempt at tugging the audience’s heartstrings in the middle of a scene of slapstick violence, clear sociopathy, and the literal narration “Time has pushed the good in everybody to the front. Eddie is the exception.”

And you’ve glibly chosen the latter, against all evidence, because it fits your narrative.

Looking further, I must take similar issue with your complaint about Dollar Bill’s behavior in issue 3, Leung.

What more, exactly, must be said to satisfy you that a hypocritical Bible-thumping homophobe is not the voice of moral reason in a scene than establishing that they are a hypocritical Bible-thumping homophobe?

You want them to express other contemptible opinions? Oh look, Dollar Bill’s only other scene in the issue is playing rape apologist.

You want someone put there to explicitly disagree with him? Because, hey wait, that happens. In the next panel after the one you posted.

You want him to dress up as a physical embodiment of antiquated patriotic hypocrisy, like he was some sort of walking political cartoon? Well there’s no way tha– oh, giant flag-themed dollar sign. Right.

So yet again, you’re cherry picking lines. But here you’re going further, and directly treating them as if they reflected the author’s opinion, claiming that this is “an attitude Cooke pointedly refrains from disavowing or ironizing.”, while ignoring the far saner possibility that Cooke believes the scene is clear and doesn’t see the need to patronize the audience. This book is, after all, targeted at adults, not kindergarteners still in the process of magnetizing their moral compasses.

You need to look it in the context of the moral dichotomy that Cooke has set up. HJ/CM are corrupt and despicable, and their homosexuality is an expression of their corruption and despicability.

There is nothing into the original “Watchmen” to suggest that Bill is a conservative Christian with strong ideas against homosexuality, so Cooke’s decision to push that angle is his specific creative choice.

Re the male bonding scenes – The first scene appears in Book 2. Bill and Eddie engage in some brotherly banter about women and beer when they overheard CM/HJ whispering about a late night tryst. Bill and Eddie exchange a look of disgust at what they have overheard. The second scene appears in Book 3. Hollis is more tolerant than Bill, but he doesn’t “explicitly disagree” with Bill. He agrees that CM/HJ are disgusting, but he prefers to live and let live. So we have two “normal” straight male responses to homosexuality – the straight male disgust at homosexuality, and the straight male reluctant tolerance of homosexuality.

And that’s as far as Bill’s characterization goes. On his death, Hollis calls him a “good man” and “good friend”. Bill’s ideas may be a bit old-fashioned, but he is still a man of honor and integrity.

Can we say the same about HJ/CM? What right-minded person WOULDN’T be disgusted at them if they are really as bad as Cooke has depicted them?

Re the rape scene – Cooke has changed the scene entirely so that rape isn’t rape anymore – it’s just a harmless misunderstanding. HJ/CM are the ones who blew it out of all proportions, and they got what they deserve when Eddie turns the tables on them and exposes them as hypocrites. Bill’s expression of sympathy for Eddie in that context is an act of brotherly solidarity and charity. Note also that Ursula, the “conscience” of Minutemen, doesn’t appear anywhere (because CM has sexistly called a “men-only” meeting). So even here Cooke has dodged the need to address how another woman would have judged Eddie’s behavior.

I agree that the juxtaposition of the scenes with HJ/CM and the pedophilia appeared out of place when I first read them. But I also think that Cooke may have been trying to show a Wertham-esque relationship between homosexuality and pedophilic behavior. Batman and Robin were notoriously linked together and comics listed as being one of the elements which led to juvenile delinquency and homosexual behavior. Maybe I am giving Cooke too much credit and thinking that he just handled it wrong–that his intent of showing that kind of ridiculous causality came across as a serious link, rather than trying to get the readers to question for themselves whether the two behaviors are appropriately linked.

As well, I consistently believe that the Comedian has to be one of the most unreliable characters when it comes to comics. Unfortunately, he doesn’t narrate, so he doesn’t come under the guise of an unreliable narrator, but I have to constantly wonder whether I can truly believe anything he states or thinks.

Good article.

This is a little off-topic, but does anyone else think Moore’s dialogue in the lesbian arguement panel is a little sloppy? Wouldn’t the p.c. yuppie woman tone down her p.c. yuppiness a little when speaking to her Penthouse-reading, blue-collar girlfriend?

Well, the point is kind of that she’s not good at doing that, which is why they don’t get along very well, right?

Not to indulge in Mooredolatry or anything— but I think it’s reasonable to have people negotiating class divisions poorly. That happens often enough in real life that it doesn’t bother me here….

Eh, I think he can be kind of ham-fisted and that this is an example. It’s still light years ahead of all other superhero comics dialogue, of course.

Excellent article; what a vilely rancid piece of work that “Minutemen” is!

>>You need to look it in the context of the moral dichotomy that Cooke has set up.

The only moral dichotomy I see is that Silhouette is good without qualification, and the rest are all corrupt at best and contemptible at worst. Night Owl comes out a bit ahead of the pack, as he says he wants to do good, but he is narrating and thus able to make his own excuses, and clearly lacks the will to go against the others in any case.

>>There is nothing into the original “Watchmen” to suggest that Bill is a conservative Christian with strong ideas against homosexuality, so Cooke’s decision to push that angle is his specific creative choice.

Sure, because it fits into his broader decision to show the Minutemen as a deeply flawed vanity project that is organizationally more concerned with its own PR than with doing good.

As for the rape trial, which appears to be the crux of your criticism, it’s not “misunderstood”, it’s covered up by the other characters for the sake of that same PR. They dance around the event by calling it “assault” because that euphemization helps them justify handling it in-house. And not just in-house, but as The Boy’s Club, purposefully leaving both the victim and their most conscientious member out of deliberations. You can’t even claim this is legitimately misunderstandable, the entire scene is interspersed with subtle-as-a-brick references to the archetypes of traditional heroism that their PR claims they are which they are failing to live up to.

This decision by the Minutemen is not meant to be lauded by the audience (also: sky blue, water wet), it is matter-of-fact documentation of a “damage control first” approach to handling sexual misconduct that is far too common even now.

What a piece of shit article….

Seriously, this entire piece shows that Leung DID NOT read the fucking mini-series. There is NO fucking white washing whatsoever of Comedian and more to the point the whole ending is one that confirms once and for all that Edward Blake is a monster, with how far he went to get revenge on those who kicked him out of the Minutemen and that he got away with it in the end.

If anything, Leung comes across as homophobic in the guise of accusing Cooke of the very thing he is engaging in and moreso, is almost gleefully cheering his utterly delusional head canon (since Leung can barely disguise his obsession with white knighting Comedian under the guise of “criticizing” the character) that Comedian won in the end and was “vindicated”.

NO Leung. The ending basically showed that Comedian was a horrific monster who manipulated Night Owl into killing an innocent man and moreso, got his lover to help him kill him. And the only thing Night Owl can do, since he knows that Blake will murder him to cover up his secret, is out him as a rapist. He can’t tell anyone what Blake did but he can make sure that he can tell everyone that Blake tried to sexually assault his teammate and have that sin at least be out in the open for the world to see.

And hell, Cooke was STUCK with Moore’s bullshit “Sally had sex with her would-be rapist and produced Laurie” reveal and had to work around it best he could. Had he not even touched the subject, he would have been criticized of white washing it by omission. And hell, the entire point of showing Blake’s expulsion was NOT to make you feel sorry for Blake but to show everyone reacting in horror at what Blake did and to set up Blake’s sadistic revenge at the very end. You are not supposed to feel sorry for Blake’s half-hearted apologies or his earlier line about being an abused child, which is clearly what Leung did, hence him writing this garbage article to passively aggressively promote his pro-Blake rantings under the guise of “criticizing” the character with a defense that shows that he is talking out his ass.

In short, this entire article is made of the worst kind of fail imaginable.

So Jesse…how do you explain the redoing of the rape scene as Laurie fighting some random villain? Why is that a reasonable choice?

Yes Jesse, if there’s one thing we can all agree on, Cooke was STUCK writing a Watchmen comic featuring a woman who had sex with her rapist. How traumatic for him, forced at gun point to write that story.

I have been thinking about this quite a bit since reading this yesterday, and especially the parallel structure of the rape images.

If we read “Silk Spectre” as an analysis of the father/daughter relationship as opposed to the mother/daughter relationship as Leung suggests, then the parallel is actually pretty appropriate. Leung argues that this particular story shows how Laurie relates to Hollis as a surrogate father, and Blake as the absent, but watchful “fairy godfather.” From the original series we know that Laurie knows she is not the child of Sally’s husband, and that she wonders who her real father was–possibly Hooded Justice.

We have the benefit of hindsight when reading this and knowing that Laurie is Blake’s daughter–we understand the irony of Sally calling Blake to step in. But the parallel of the rape scene also plays into that irony, what we as readers know that Laurie does not.

Laurie is the same age in this piece as Blake was when he rapes her mother. At the end of the original series, Laurie lets us know that she is more like her father than she would previously admit, but embracing both his look and his methods. By showing the parallel panels, we see that Laurie has the same potential for brutality, at least physical brutality, that her father does. If this is a story about fathers and daughters, then it makes visual sense to parallel the two scenes to show that Laurie is indeed her father’s daughter.

I do think that, based on this, that Minutemen looks like a pretty awful piece of garbage filled with wrongheaded decisions, and aesthetic missteps. StiIl, I do think some of William’s claims here don’t stand up to scrutiny (like Irrelevant’s above). The scene where Comedian calls his colleagues a “bunch of fags”, threatens to kill them, etc. (and is then followed by the “ironic” cartoony “hero” panel-“What a Man!”) really doesn’t make Blake look positive. Rather, it suggests he is the monster we remember from Watchmen (if anything, more monstrous, since Blake has his human moments in the original). The scene in which Dollar Bill is homophobic doesn’t suggest much more than that he is homophobic (incredibly common stance at the time…and even now, believe it or not). The fact that the Minutemen cover up the rape doesn’t mean that Cooke is doing so (in fact, I think he probably assumes we read Watchmen and “saw” what really happened, etc., so any counter-claims by characters come off as patently false. Sally talks about the cover up for PR purposes in the original, I think.) I haven’t read Minutemen, am unlikely to, and don’t want to defend it, but some of the arguments made here aren’t actually supported by the evidence William himself presents, which then makes me somewhat suspicious of the other criticisms.

I can’t speak to Cooke’s portrayal of HJ and CM, and if it’s as negative as William says, then it’s an atrocity that deserves to be critiqued…Moore’s portrayal of HJ really isn’t pleasant though. In Watchmen, HJ is a sadist who gets off on other people’s pain (and not only in a consensual, we-all-agreed-to-it-beforehand kind of way), something Eddie has figured out and exploits. As William notes above, his brutal beatings of criminals is as disturbing as Rorschach’s. Is his sadism and brutality associated with his homosexuality? Maybe not directly, but it treads kind of close to some invidious stereotypes. Captain Metropolis comes off somewhat better, but is the ineffectual, passive, stereotypical “bottom” who rarely, if ever, has any depth to his character beyond that.

If anything, it would have been nice had Cooke countered these stereotypes in some way rather than deepening and exacerbating them…but I don’t think Moore’s portrayal of either of these characters is especially nuanced…and it’s often not very positive (restaurant scene notwithstanding). To be clear, I’m not saying that all portrayals of gay life need to be positive, but the gay male characters in Watchmen tend to be both shallow (drawn with broad strokes) and verging on the negatively stereotypical. The other example is Sally’s husband, whom she implies may be gay at one point in the text pieces.

The choice of having Laurie wearing smiley-face earrings, and re-enacting some of her father’s moves/actions even makes sense in some ways, since the “like father/like daughter” theme is definitely part of Watchmen (particularly in the clothes she wears…the yellow pajamas, and, at the end, the shift to black leather…reflect her father’s similar shift). Obviously, Laurie is formed by her mother and their reconciliation is touching…but the influence (genetic and subconscious) of Blake is also important to her character.

The choice of having her kung-fu moves reflecting Blake’s sexual assault of her mother is just terrible, though….even repulsive.

For these reasons, I kind of feel like Cooke IS trying to use/deepen the themes and subtleties of the original, but that he is incapable of doing so, is incredibly clumsy, etc…which leads to both a lack of subtlety and offensiveness. Moore investigates sensitive and complex issues and treats them, for the most part, with respect and insight. Based on the examples above, Cooke’s attempt to deal with those same issues seems incredibly ham-fisted, but I’m not sure I’m willing to buy the claim that it turns Blake into a “good guy”–or even an attractive anti-hero.

Maybe I’ll read it if my library gets a copy…if I can stomach it

Jordan, the problem is that the parallel suggests not just that she is her father’s daughter, but that she is her father’s daughter *at the moment he is raping her mother.* If there’s irony, it’s hard to figure out how to read it in a way that isn’t really offensive. Are we supposed to be laughing at Laurie because she doesn’t know her father is a rapist? Are we supposed to see her cool beatdown of the bad guy as reflecting moves she somehow inherited from the cool beatdown of her mother? Maybe there’s another less vile explanation I’m not getting, but I just don’t see how reinterpreting those panels is anything but a horrible idea.

by no means am I suggesting that it isn’t offensive…I agree with eric, that cooke is trying really hard to catch the nuances of the original, he just fails at it. If we were able to remove the sexual aspect of Blake’s original assault, and it was just violence against women (and I don’t mean “just” violence against women–that is its own level of abhorrent) the parallel matches a bit better. I am not trying to be an apologist for Cooke because I think the more you analyze it, the more it breaks down and fall into the realm of poor idea. I am trying to figure out why he may have thought it was a good idea, and why Amanda went along with it.

That scene is the only one in which we see Blake doing physical, hand to hand violence. It had to be that scene that was paralleled, because there is none other in the original. The problem is that it becomes impossible to remove who Blake is beating from those panels. Like I said, I think this is what Cooke is going for–showing that she can mimic her father’s moves, but it does come out in poor taste because you just can’t take Sally out of the picture and keep it faithful.

Jordan, that makes a lot of sense actually — that is, that it’s the only scene of Blake fighting, and they wanted a scene of Blake fighting, so they used that.

Which was a terrible, terrible idea, obviously.

I do wish the people commenting on part 2 would reply in the page on part 2. It’s a substantially different and far more substantial critique than that of Minuteman, and we’re tangling the threads of conversation.

Ah well…welcome to the internet. Everything’s linked….

I’m all for acknowledging the clubhouse complexities or whatever. But am I looking at the same panels as you guys wherein the Comedian gives a Craig-Thompson-meets-Gone-With-The-Wind ode to self-forgiveness while the woman responds in silence? Followed by the panels where he fucks the same woman in an intentionally erotic cuckolding scene that was magicked up in spite of canon? Or the fanfiction-worthy scene where he recognizes the little girl and has a personal emotional transformation?

I haven’t read the books, but based on what I can see here, that’s some mature and rich writing. If context makes those scenes into thicker moments, please let us know.

Noah: “…the problem is that the parallel suggests not just that she is her father’s daughter, but that she is her father’s daughter *at the moment he is raping her mother.”