Note: This review of Abstract Comics was written close to three years ago. It was proposed to Art in America in the fall of 2009 and submitted for publication that November or December. Overbooking in the book reviews department, I was told, delayed its publication. Finally the following summer, sensing its age as a review and the need to jumpstart things before it was too late, I offered to expand the article into a feature length essay on the wider subject of abstraction in recent comics, including figurative and/or narrative ones like Dash Shaw’s Body World, Joshua Cotter’s Driven by Lemons, and Brian Chippendale’s If ‘n Oof. That proposal was likewise accepted, but then the magazine’s head editor was ousted. The new head editor, after another six months’ consideration, finally paid me a kill fee. I thought I might write the expanded version nonetheless and submit it to an academic journal, but then got busy with other things and lost interest.

If I were to write on this topic today, there are many things I would change. It is, however, precisely this thinking that has kept this piece buried inside my computer, where it does no one any good. Thank you to Andrei Molotiu and Derik Badman for pushing me in recent months to publish the review regardless. So here it is, more or less in the state it was three years ago. Keep in my mind it was written for an art world publication. There were also word count restrictions, hence its clipped nature. What you see here, if I remember correctly, was already about 300 words over length. I said I would change many things today, including its tone, but the core opinions and suggestions I still stand by.

*******************

Since the 1990s, there has been a rising tide against the word in comics. It has begun to gel into something like a movement, made up of artists, critics, and editors alike, involving both the creation and promotion of new wordless comics in a variety of genres as well as the republishing and anthologizing of related work from the past.

So-called “abstract comics” is one of the more extreme fronts. It names a form of wordless comics that not only dispenses with the word, but also those things traditionally allied with it, like speech, sound, plot, and interiority. Abstract comics has been a fringe genre, disseminated largely through blogs and self-published and small press booklets. With the publication of Abstract Comics: the Anthology (Fantagraphics, 2009), it has gained a more secure foothold in print.

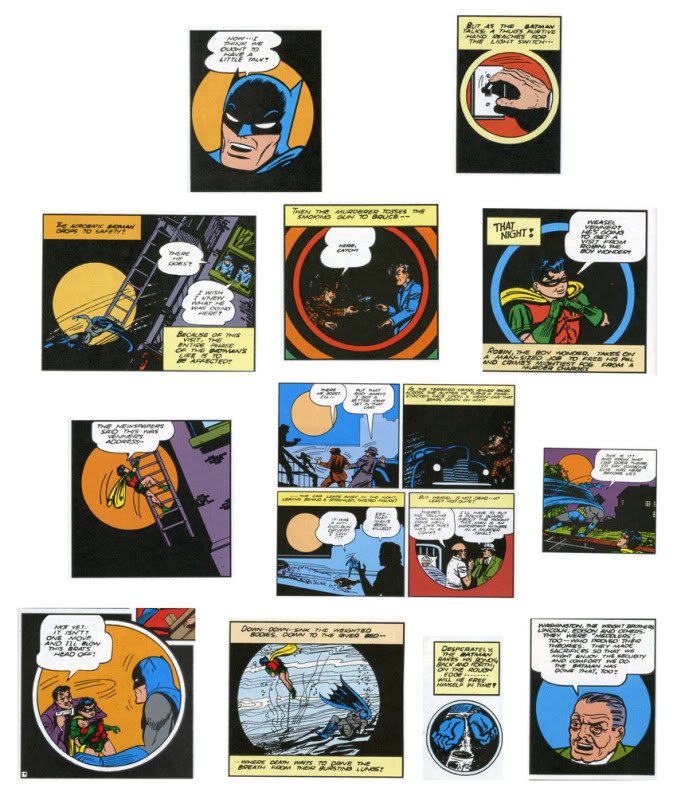

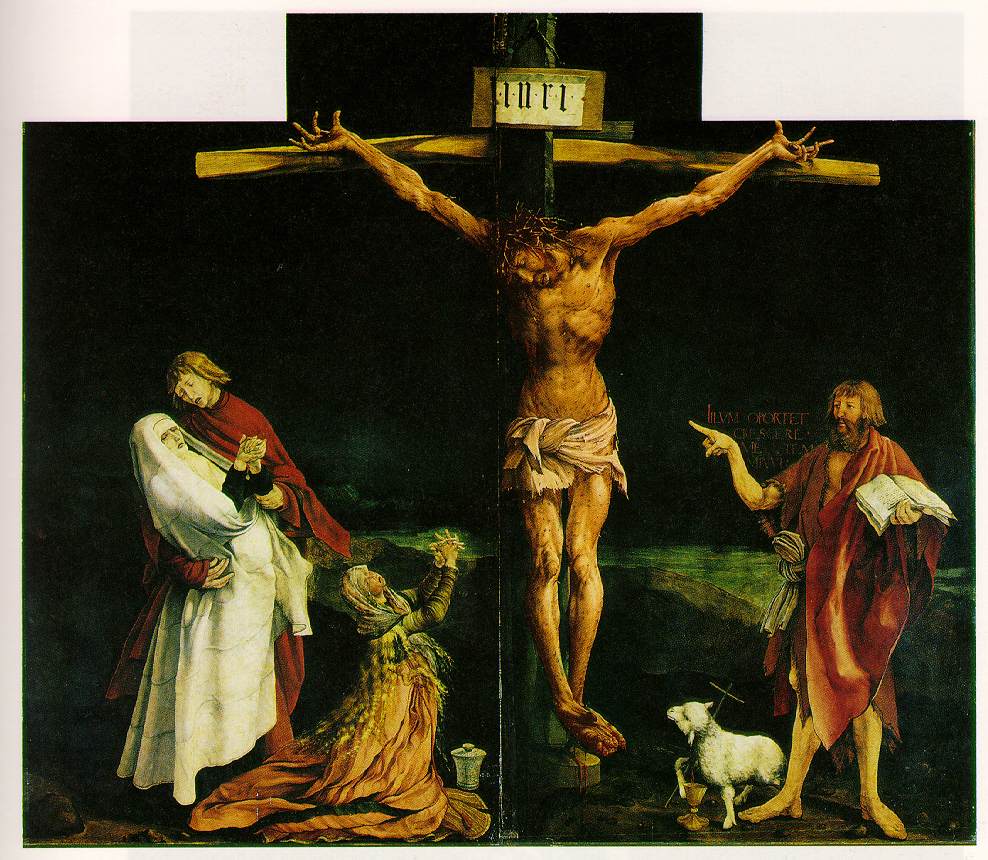

The book collects work from 1968 to the present. It includes comics luminaries like R. Crumb, Gary Panter, and Lewis Trondheim, but is focused on new names from the past decade. Most of the work is deeply indebted to modernist abstraction, from Kandinsky’s dispersions and Cubist papier collé, to the nested squares of Albers and Abstract Expressionist blots and drips – all typically set into narrative motion across a handful of panels or pages.

Museum modernism also weighs heavily on the framing of the anthology. In his introduction, Andrei Molotiu, artist, art historian, and blogmaster of the same-titled Abstract Comics site, describes the genre as a whole in terms derived from a mix of vitalist philosophy and a classical modernist model of reflexive reduction. He writes:

Reduced to the medium’s most basic elements – the panel grid, brushstrokes or penstrokes, and sometimes color – they [abstract comics] highlight the formal mechanisms that underlie all comics, such as the graphic dynamism that leads the eye (and the mind) from panel to panel, or the aesthetically rich interplay between sequentiality and page layout.

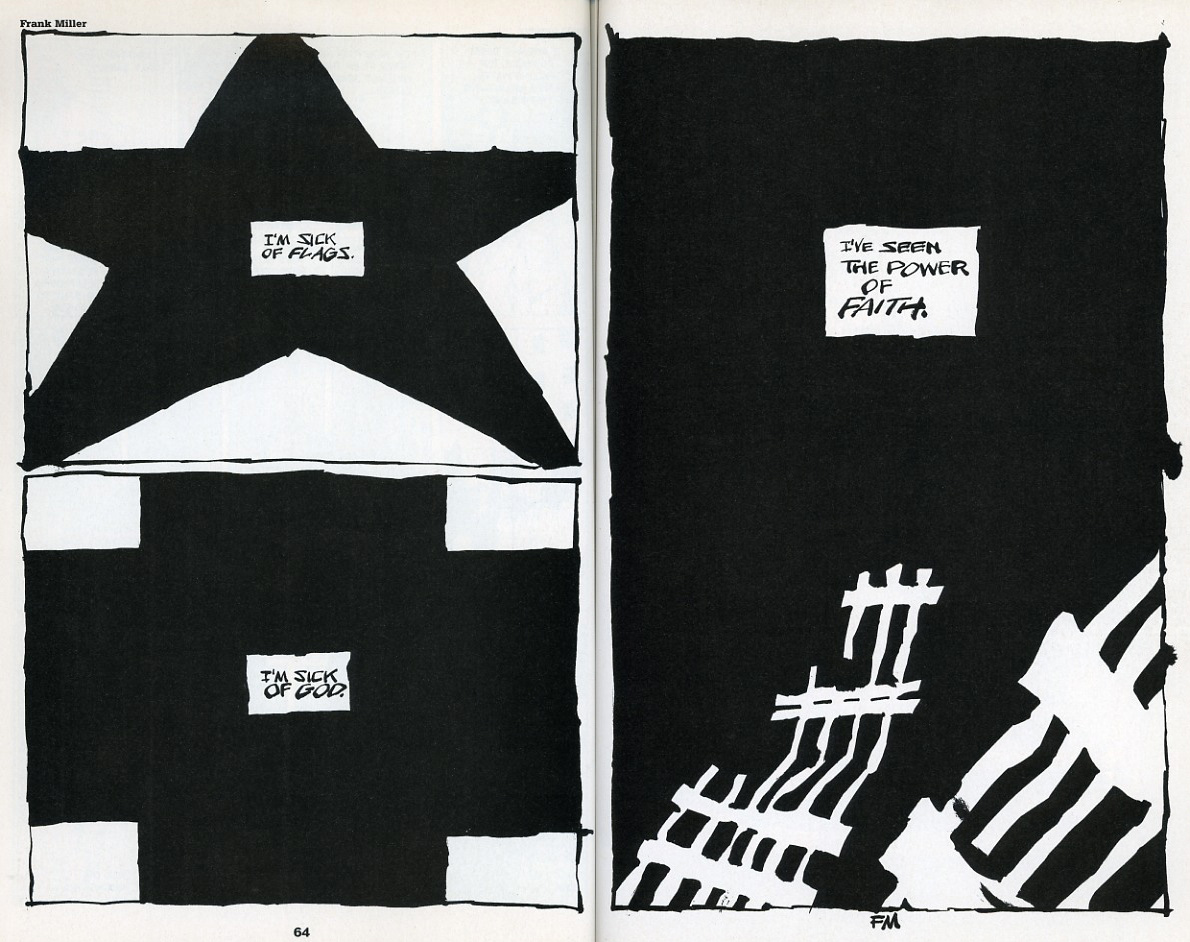

In the same vein, Molotiu describes standard narrative structure as an “excuse to string panels together” and abstract comics as a distillation of the medium to the “feeling of sequential drive, the sheer rhythm of narrative or the rise and fall of a story arc.” In the artist profiles at the end of the book, Mark Badger – contributor of a maximalist geometric abstraction in comics form – laments how images in comics are “unable to claim their real power” while subordinated to narrative or representation. “Hopefully,” he continues, “this book will be one shot in claiming back comics from the typists.”

Abstract Comics thus offers itself as a manifesto in the tradition of high modernist art, without the extremism of its historical predecessors, but nonetheless sharing their characteristic denigration of narrative and the verbal sign as well as their calls to power through purification. The anthology, unfortunately, does not make the strongest case for the vigor of the movement it promotes. Much of the collected work is visually weak, and the modernist formalist discourse to which the book is indebted ceased to have any real traction after the socio-political and linguistic turns of art in the 1960s. Molotiu expends much of the introduction excavating precursors for this “genre without a proper tradition” from the oeuvres of art-world masters like Kandinsky, DeKooning, Alechinsky, and Johns, with only passing mention of relevant precedents within the comics medium itself. Trying to legitimize comics vis a vis the art historical canon can sometimes be self-defeating, and here it has the unintended effect of casting abstract comics as little more than a super-belated reworking of formalist painting. Especially considering the online presence of “abstract comics” and the computer-based creation of many of the contributions, it would perhaps have been more fruitful to explore the relationship of the genre to the return of various forms of abstraction in the computer age, beginning with Neo-Geo in the early 80s and then internet art and laptop music after the 90s. Instead, the top two-thirds of each page of Molotiu’s introduction are given over to rows of dingbats, a cute waste of valuable space and another statement of preference for pure aesthetic form over verbal discourse. One is left to dig through the artist profiles of Abstract Comics and the personal webpages cited therein to get any real sense of specificity to individual works and the promise that some do hold.

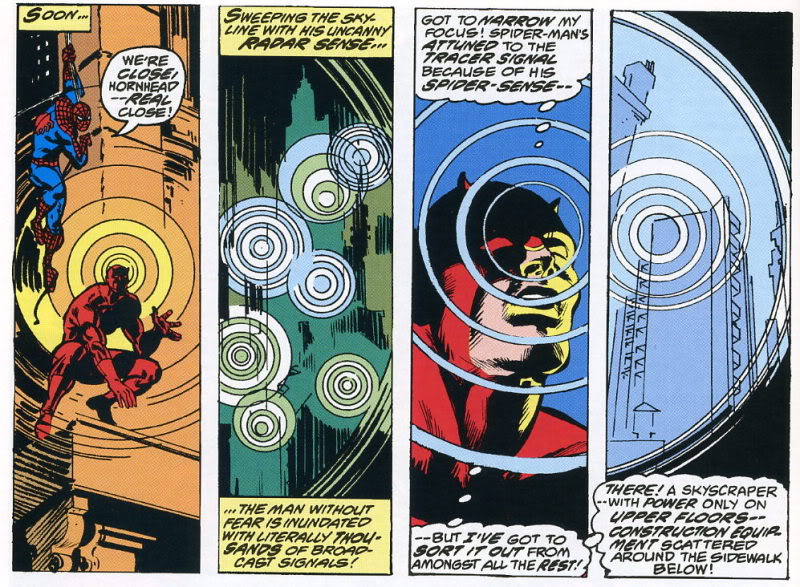

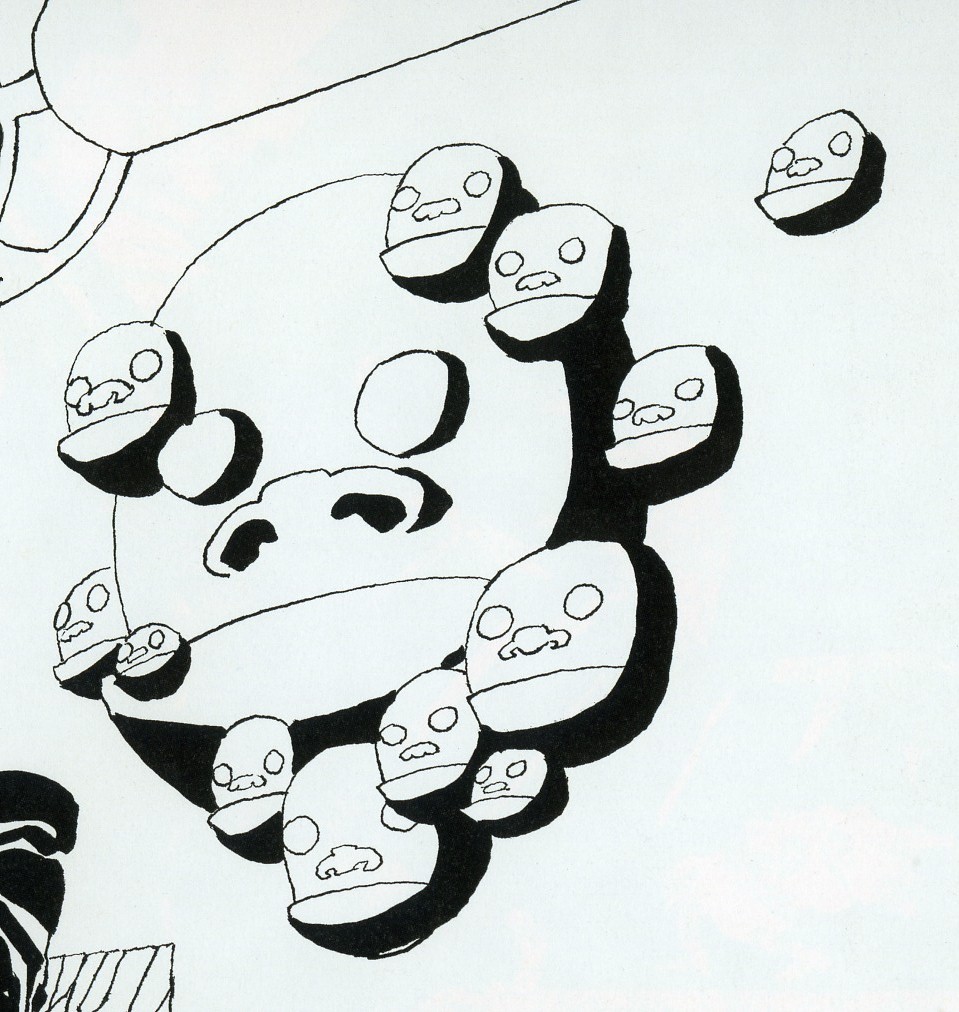

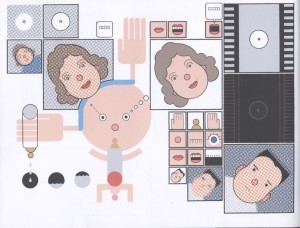

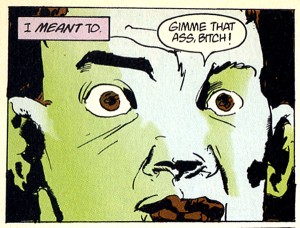

As is clear to any reader, the dominant trope of abstract comics is metamorphosis. Molotiu heralds work that “tells no stories other than those resulting from the transformation and interaction of shapes across a comic page.” Andy Bleck’s Haring-esque work is typical. Anthropomorphic blobs twist and tangle in goofball dances that are half cartoon tribal mating ritual and half protoplasm on a wet mount microscope slide. The contributions of the two most prominent Europeans in the anthology, Trondheim and Ibn al Rabin, make it clear that the defining figure of metamorphosis is the amoeba. Both of their works are short comedies featuring blobs swallowing nuclei and other blobs. There is a basic vitalist conceit at work here: to boil the comics medium down to pure formal dynamism entails exploring also the most basic forms of animate life.

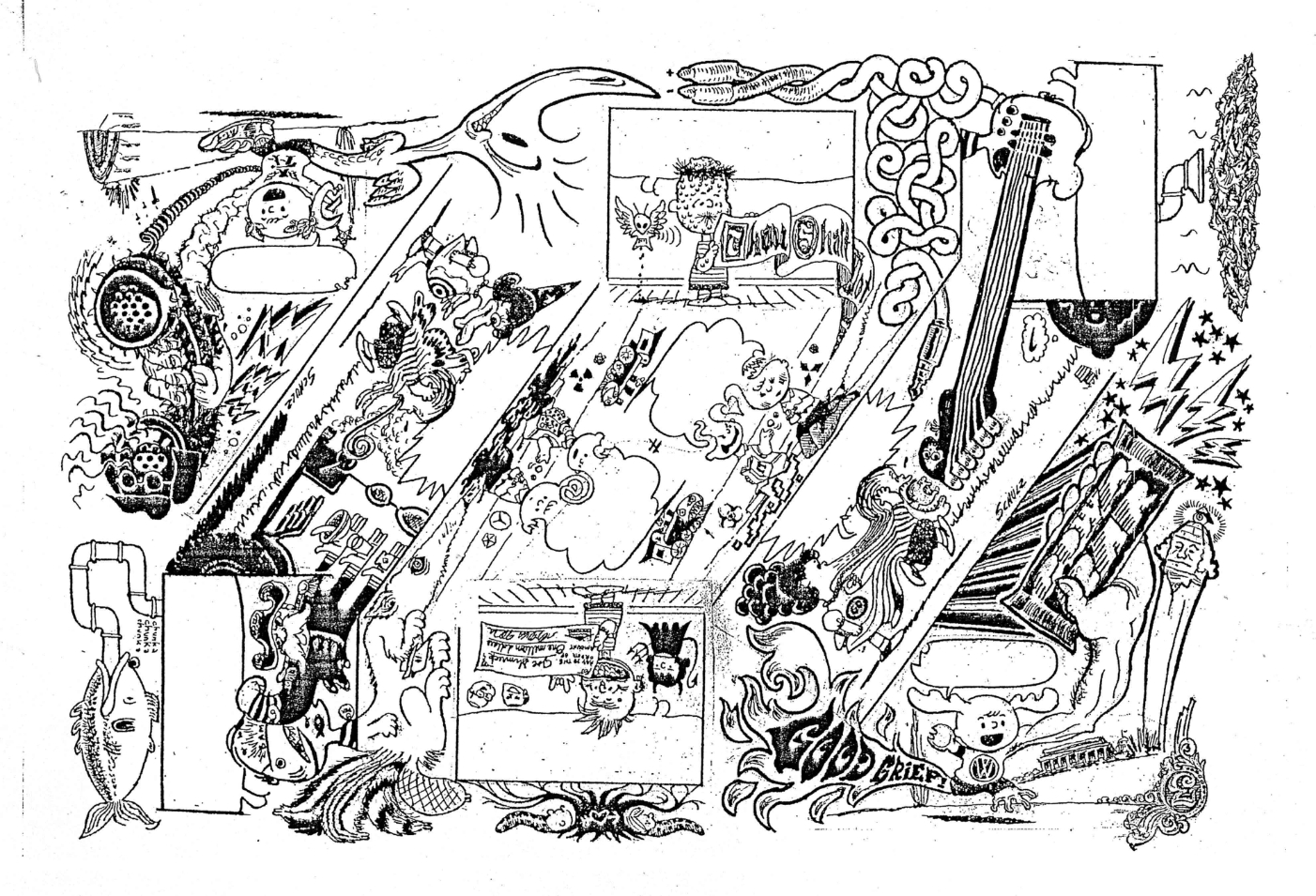

by Andy Bleck

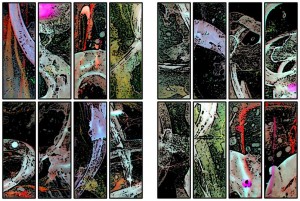

Most of the works are as entropic as they are dynamic, involving not only the transformation of form and energy, but also their disorganization and dissipation. Molotiu’s own works are a case in point. Produced with the aid of a scanner, “The Panic” begins with compound masses whose biomorphism once again evokes the biology lab. Over the course of a handful of panels, the masses pull apart into small globules.

Chaos, similarly, is a recurring motif. Alexy Sokolin’s “Life, Interwoven” layers ballpoint pen lines until almost the entire page is obliterated. Tim Gaze’s untitled collages are a gore-fest of inky smears and splatter, further mutilated through a technique similar to the cut-ups of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin. Billy Mavreas’ “Border Suite” again evokes the cut-up, now run repeatedly through a copy machine until all that is left is disintegrated borderlines and dispersed dust motes. In Abstract Comics as well as other statements on “sequential dynamism” in comics, Molotiu makes the musical analogy to opera. From these works, however, it is clear that noise and glitch aesthetics would be more apt in some cases.

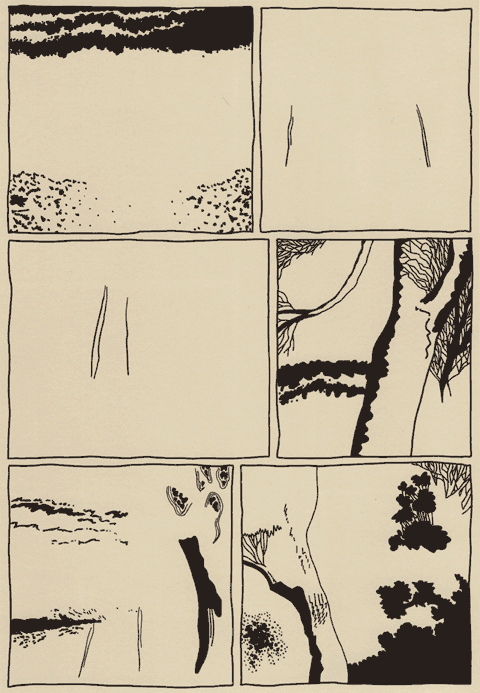

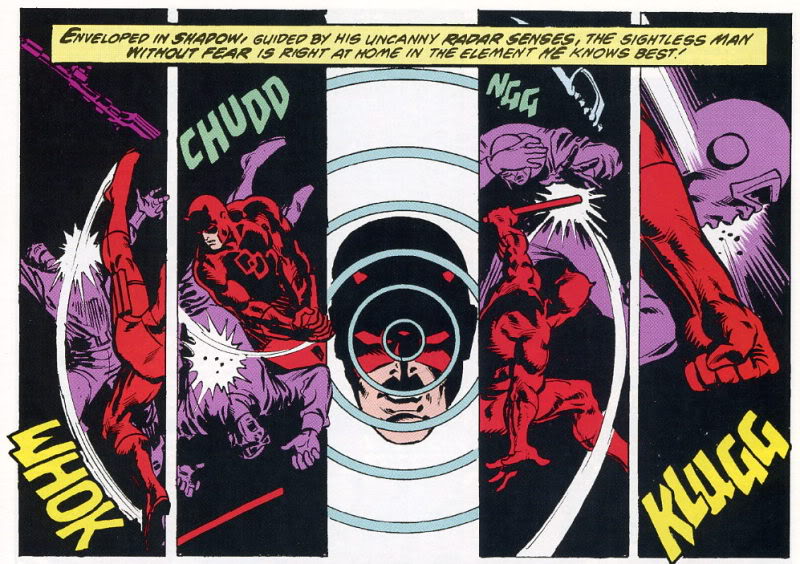

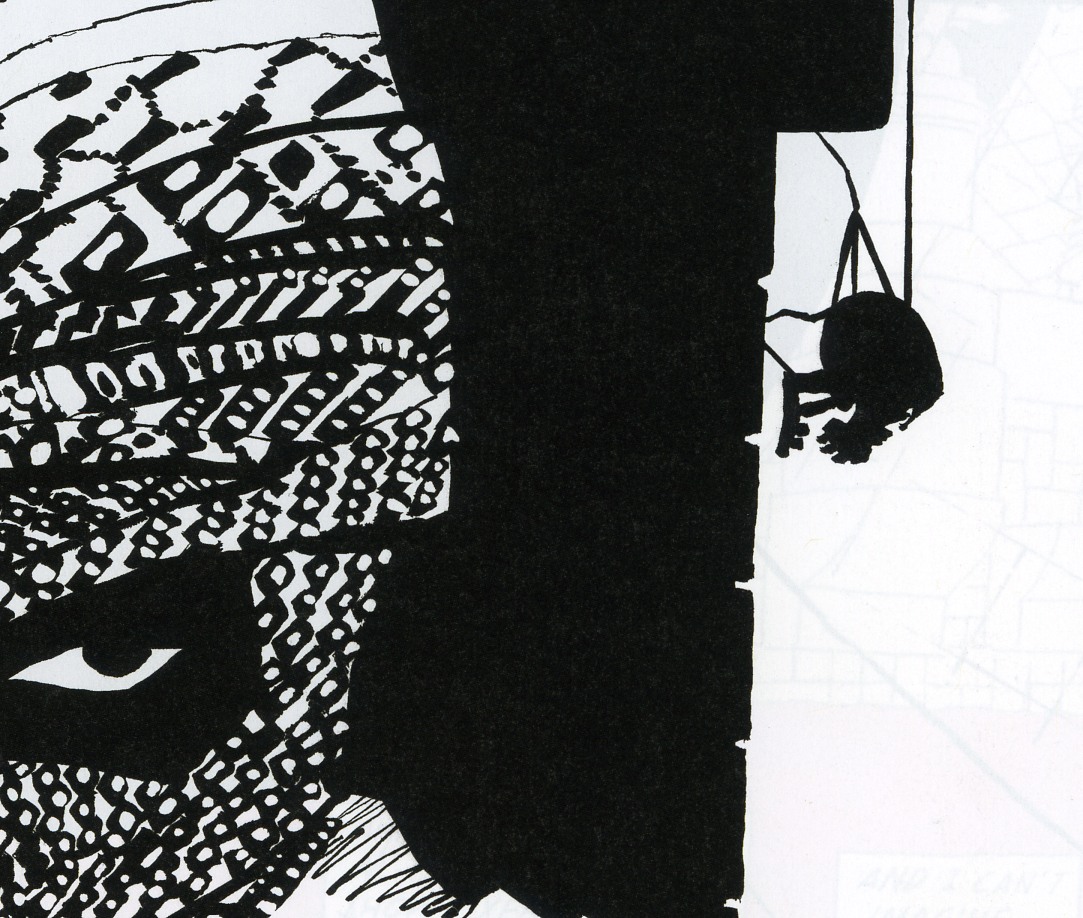

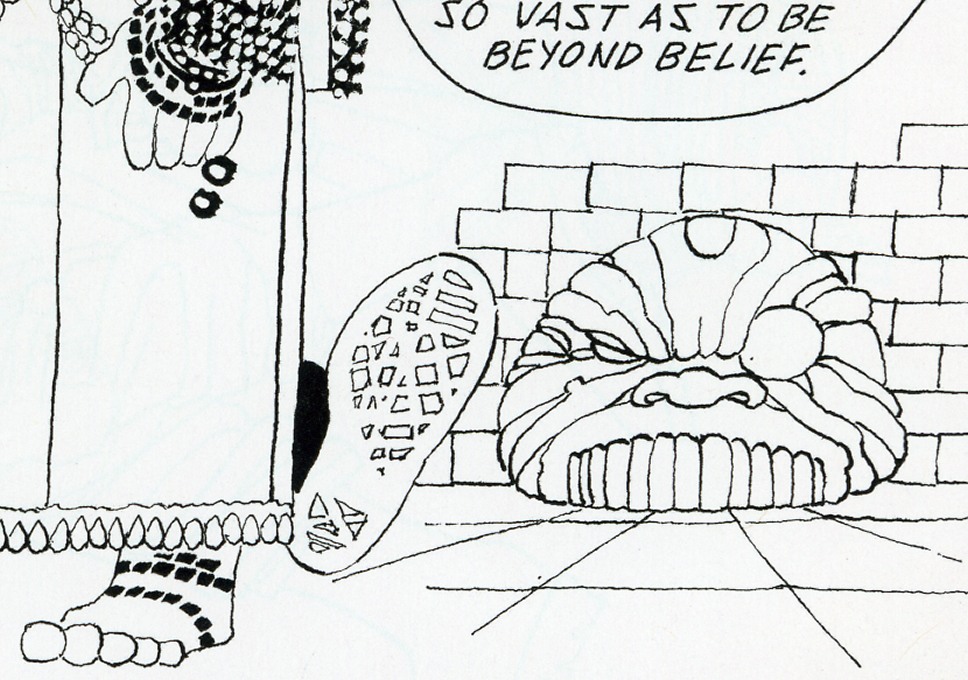

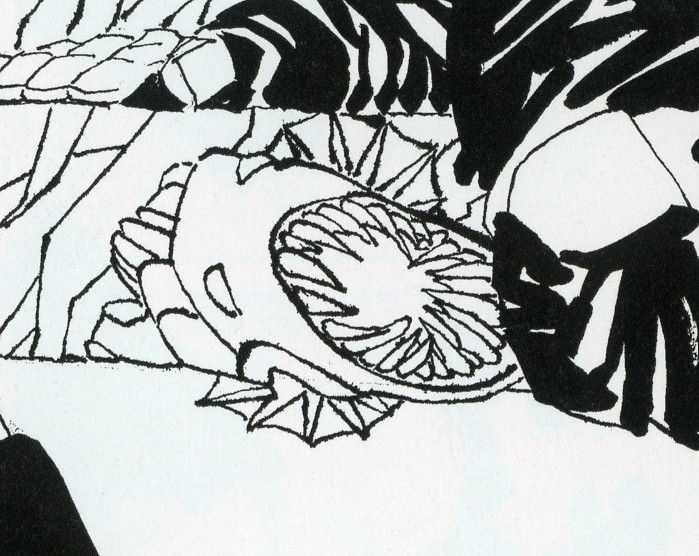

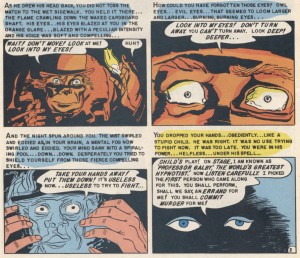

Other works also manipulate source material. Proprietor of the reliable MadInkBeard blog, Derik A. Badman’s Flying Chief is one of the more intriguing contributions to the anthology. He has redrawn panels from a 1950 Tarzan comic without the characters, words, speech balloons, or captions. More so than abstraction or entropy, this strategy of absenting is highly effective in frustrating the viewer’s desire for an organizing figure. Badman’s image of a world without human agency raises more pointed questions than other contributors’ protozoan land before time and scenes of cosmological chaos.

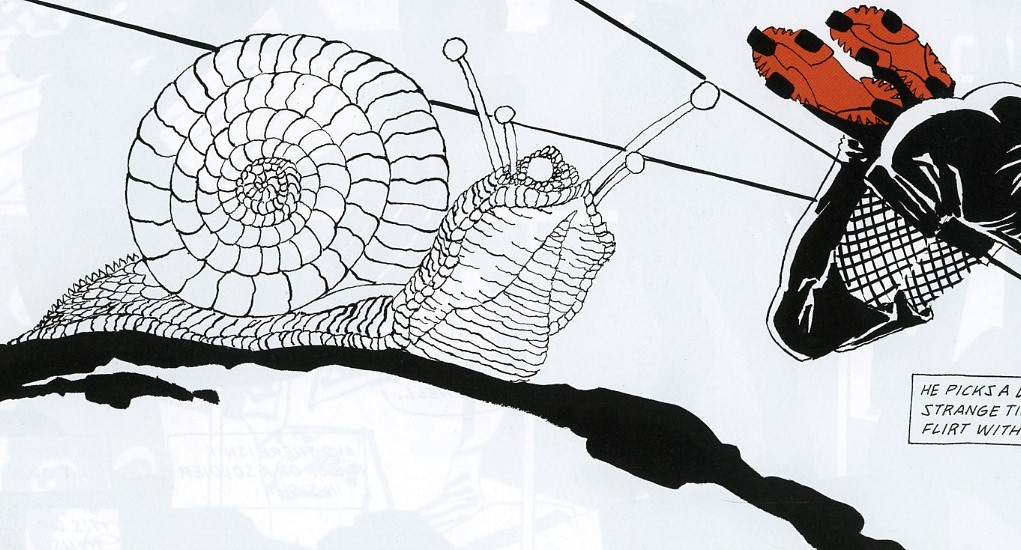

Derik Badman, “Flying Chief”

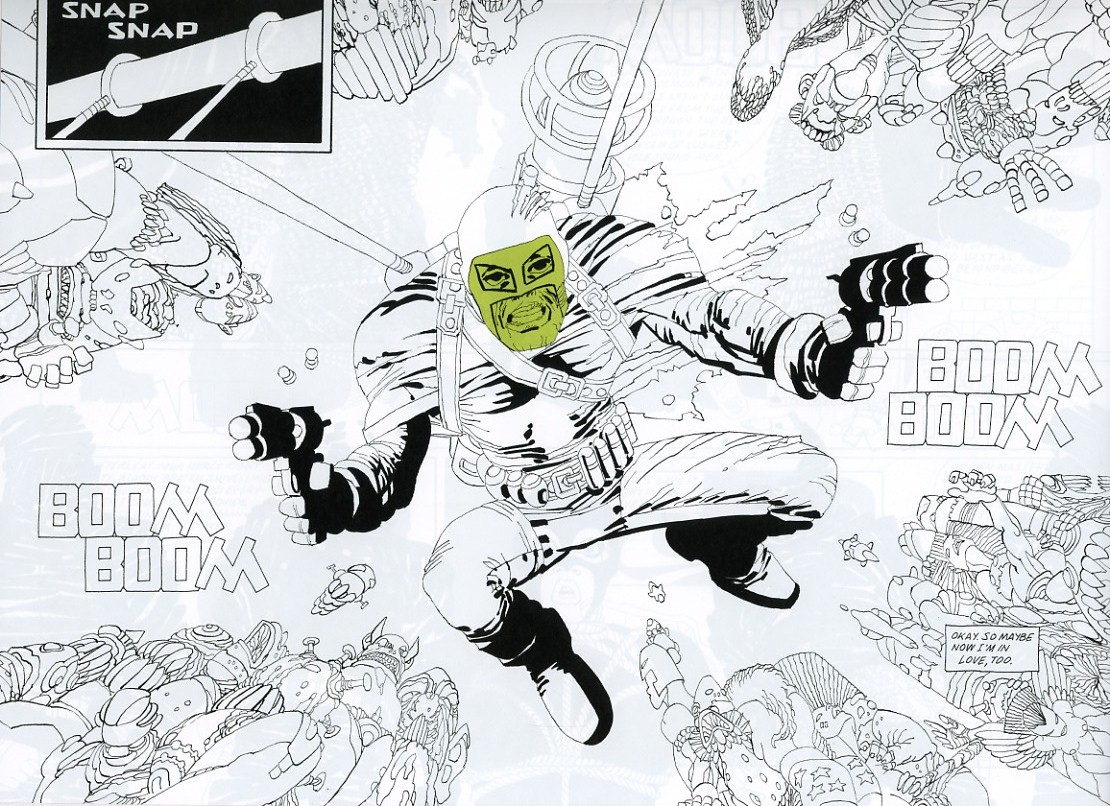

Noah Berlatsky also runs a comics blog, The Hooded Utilitarian. His two one-page works are also in this appropriationist vein. He has taken pages from Asterix and X-men and redrawn them in such a mutilated fashion that frames and figure-ground relationships are splayed and then refused into an abstract mesh. There is a strong bit of Kandinsky in the results, but it’s also important to perceive amputated bodies akin to those of early Dali or later Sue Williams.

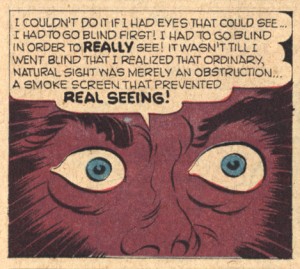

In these, as in a number of works in the anthology, there is an interest in what might be termed a logic of “vestigiality”: the organ divorced from its original function but still maintained, so that it oftentimes comes to impose upon the organism that had abandoned it. Might this principle also underlie the metamorphic comics? After all, their plasmatic substances have a striking resemblance to the spongy, pneumatic contours of the speech or thought balloon. If so, it seems that the abstraction of comics against the word and its supports is never total, but rather marked with traces of partial amputation. Abstract comics share this feature with many wordless comics, from pantomime works that gesticulate histrionically to make up for the ban on verbal expression, to indie comics around themes of melancholia, speechlessness, and pre-linguistic primitivism.

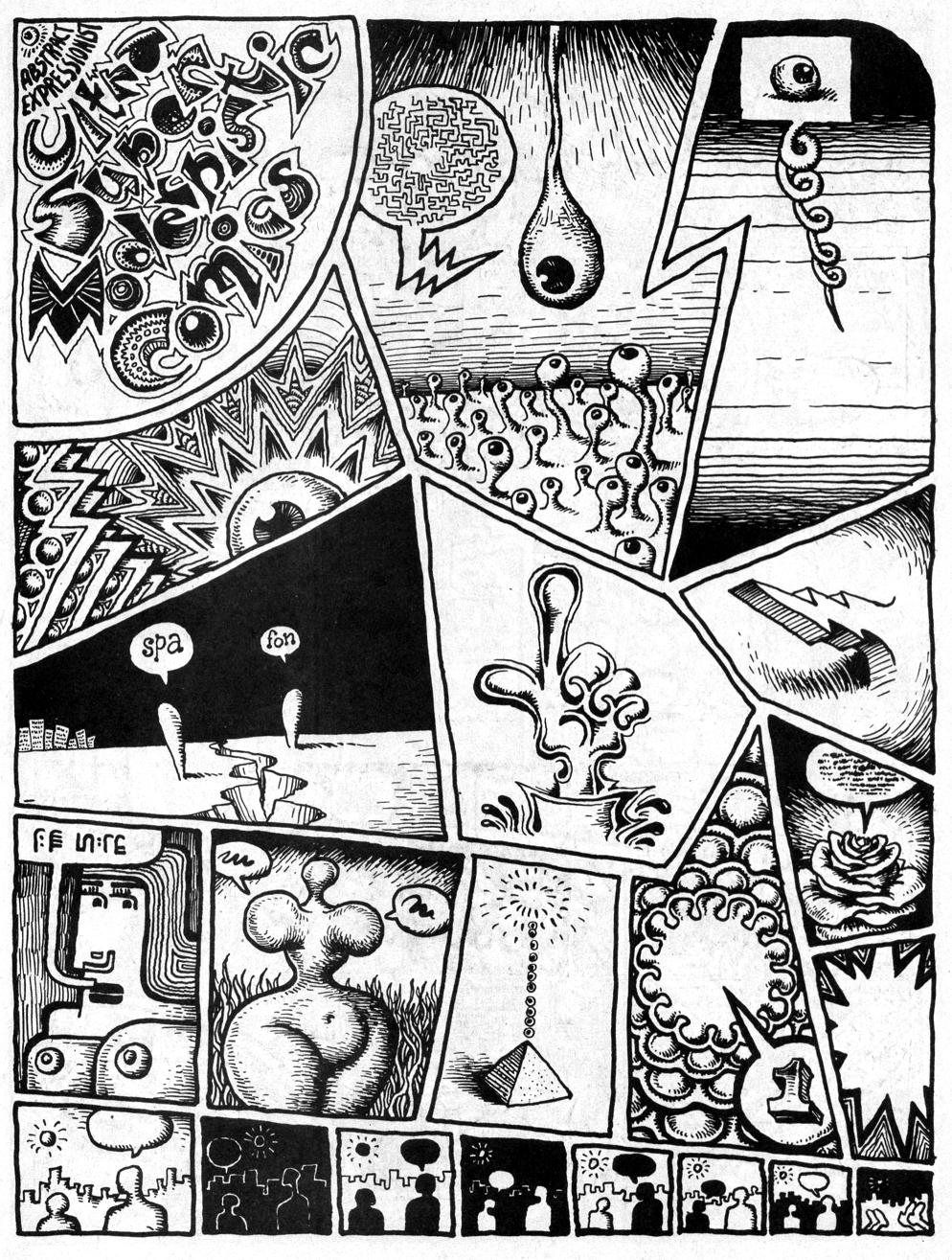

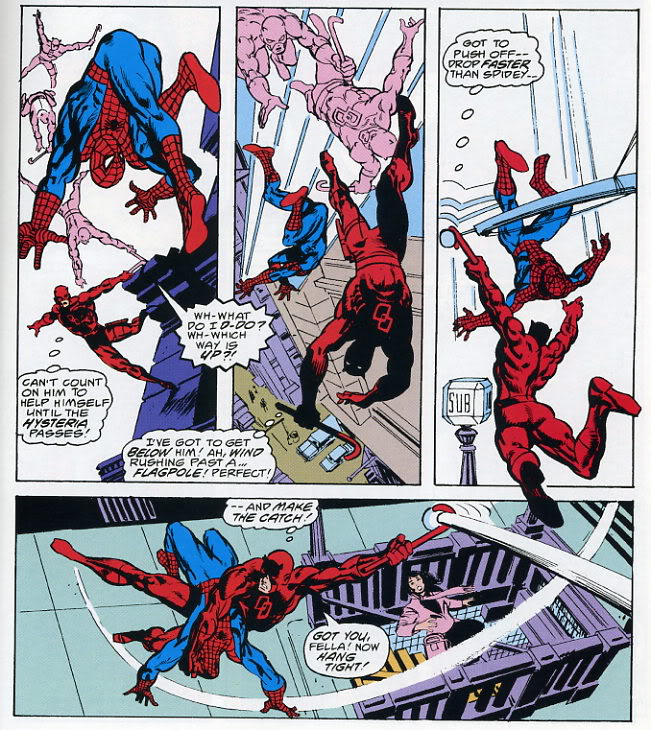

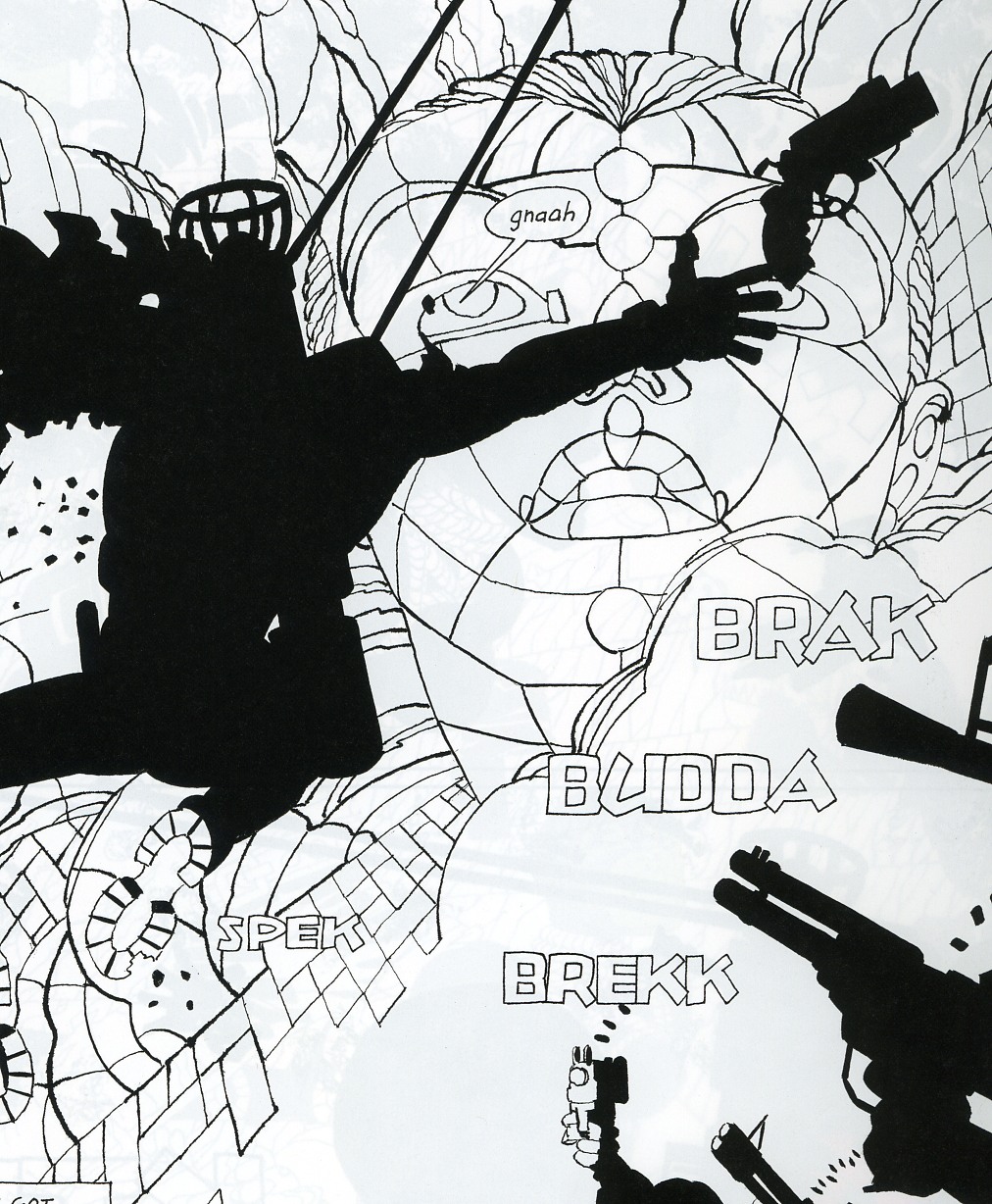

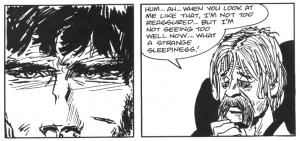

It is curious that Abstract Comics opens with R. Crumb’s “Abstract Expressionist Ultra Super Modernistic Comics,” first published in Zap Comix no. 1 (1968). First of all, its principle of non-sequitur juxtaposition is quite at odds with the smooth, linear sequentiality or serial modulation that characterizes most other works in the anthology. Secondly and more importantly, Crumb’s work was meant as a derisive parody precisely of the kind of genuflection to high modernism that Abstract Comics represents.

R. Crumb, “Abstract Expressionist Ultra Super Modernist Comics

Crumb is not alone. Burlesque has long served as a kind of prophylactic for comics artists against the perceived obscurantism and puffery of high art. A few years ago, designer Craig Yoe popularized an adequately lowbrow name for this mindset: “arf,” which is Popeye’s laugh, but comes off as a portmanteau of “art” and “barf.” At the very least, Abstract Comics represents a welcome willingness to look upon high art from the perspective of comics without such juvenile anxieties. One hopes that the future of the genre is towards aesthetic paradigms with greater contemporary relevance.