Excepting perhaps those of Metallica and Ridley Scott, there are few career arcs in recent American popular culture (an association he would despise) whose plummets have felt as sickeningly steep as that of Chris Ware. Ware more so for me, as a proto-budding comics artist at one point in my life, because he is uniquely responsible for dramatically re-enchanting and subsequently de-enchanting my relationship to the comics medium. I am willing to own my sour grapes. But there is only one reasons, in my mind, to direct aesthetic bile, which is that there is a consensus in support of a creation that deserves but has not received critical questioning. A corollary justification, which applies in this case, is when different portions of an artist’s work are not executed at the same standard, with no apparent effect on his popularity or legacy. This kind of brand-deterioration (or “falling-off”) is familiar in its causes and effects, but bears some contemplation nonetheless.

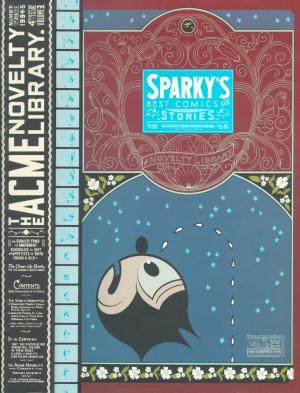

Ware’s Acme Novelty Library #4 was the first comic book I bought in Chicago in 1996, at a justifiably renowned bookstore dubbed “Quimby’s” in honor of Ware’s mouse character. AN #4 had tiny comic strips within massive comic strips, full of morose, bitter gags without punchlines, conveying mute anguish and casual cruelty. It had backwards comics. It had absurd advertisements in absurdly minute print. It had cut-and-fold sculptures. It had microscopic comics that read like animation filmstrips, and big morphing panormas, and everything rendered in a McCay-esque style that, despite its schematic depthlessness, made a flat page seem like a transdimensional portal rather than a surface. A compact exemplar of Kant’s “mathematical sublime,” it seemed to uniquely exploit everything that made comics different from books, art, or moving pictures of any kind, historically as well as formally.

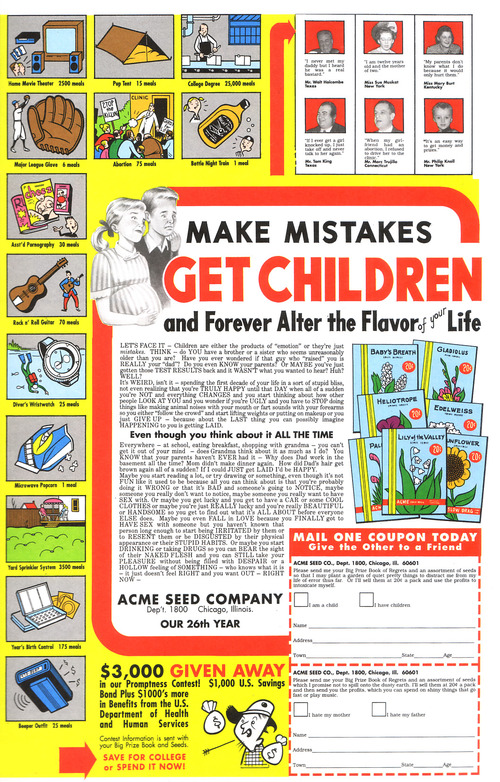

Clearly I love Acme Novelty Library #4 and Ware deserves to be fondly remembered for it, along with pretty much all of his ‘90s output. No one can take that away from him. The advertisements alone: “Make Mistakes, Get Children, And Forever Alter The Flavor of Life!;” “Large Negro Storage Boxes!” (this an advertisement for prisons); “Sexual Partner Sent To You Within Six to Ten Days!”;” “Irony!;” the list of bleak, brutally sharp promotions goes on and on (all exclamation points implied). Allow me to take one excerpt from a bit more detail, from the staggeringly tongue-in-cheek “Popular Television Programs on Cassette!,” describing the tapes’ content as provided by “your own personal video tutor:” “You’ll trace a summary of major themes, characters, plot lines, and the particular qualities that make each show so appealing to the average Amercan dumbfuck.”

Well put. And it’s not that I only appreciated his work when it was vulgar– it was rarely vulgar. But it was unrelentingly harsh. Compare this with the November 27, 2006 New Yorker cover that featured two Thanksgiving dinner tables in Ware’s trademark orthogonal perspective. One was from America’s temporally-indeterminate innocent past, and featured people having interactions (meaningful ones, to be sure), while, at the contemporary table, everyone was staring at the flatscreen TV. It’s like an edgy version of Norman Rockwell, except that Ware’s blunt nostalgia faithfully emulates Rockwell’s nadirs of treacle and falls short of his occasional glimpses of epic drama. The Thanksgiving scene echoes Ware’s equally drab, generic, competently banal depictions of people staring at cell phones. Instead of, you know, each other. Or, even better, authentically old-timey print media.

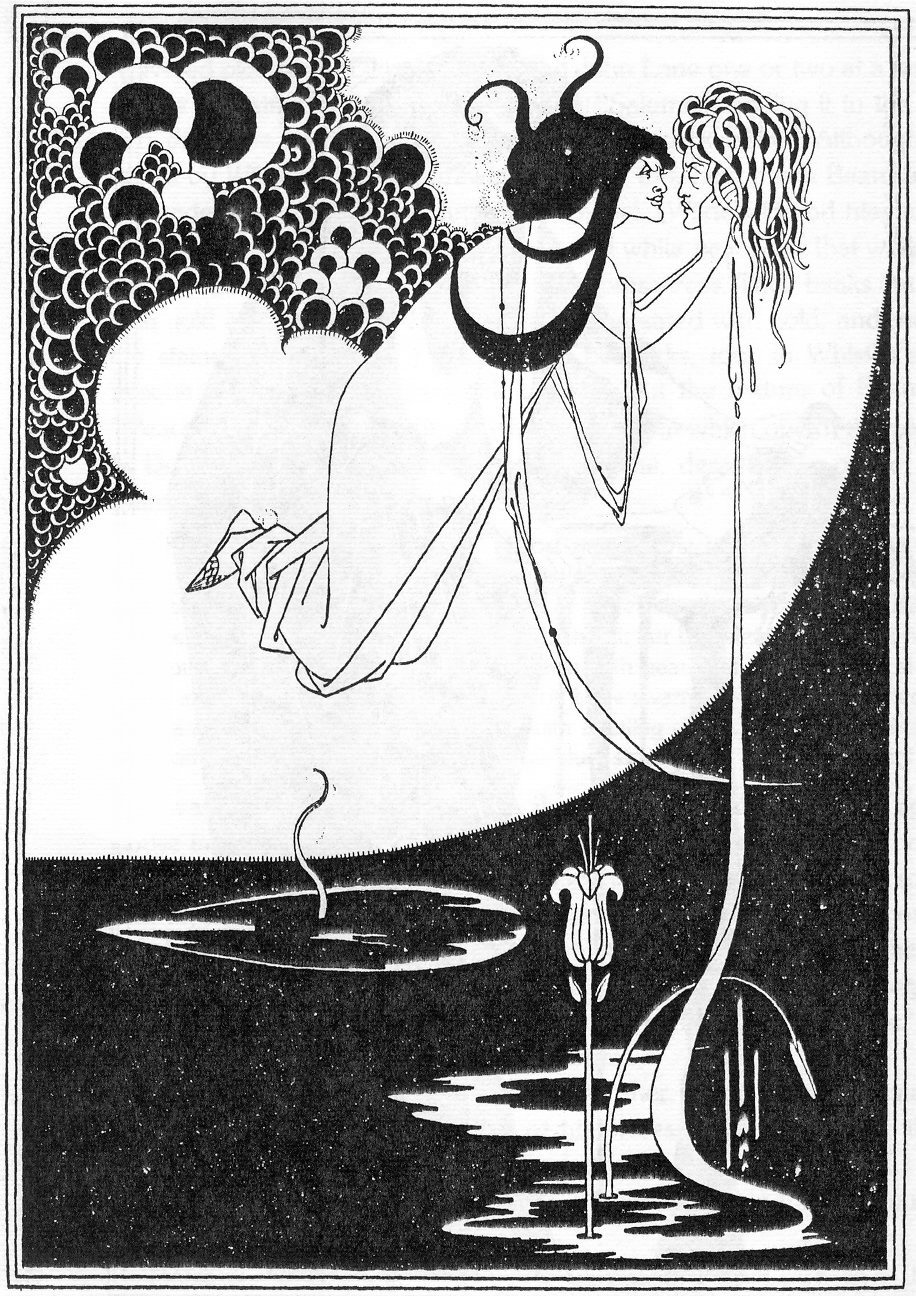

The series Ware worked on after the first Acme Novelty books– Jimmy Corrigan the Smartest Kid on Earth, Bramford the Best Bee in the World, Rusty Brown, Building Stories, — have gone from grim to dismal to dull. Originally anchoring his stories in surprising juxtapositions of style and content, forcing the reader’s eye to maneuver through dense, clamorous riots of clean, graphic Constructivism, florid Art Nouveau, and moments from throughout the history of humor and fantasy comics, not to mention experimental animation, his mash-up of high and low culture worked much like Beckett’s interpretation of vaudeville in Waiting for Godot. The snarky pathos fed a battery of nihilistic tension, to be released in the searing vitriol of the avant-garde, a pathway to creative freedom in defiance of convention. How did we end up with lame bubble people barely mustering the strength to rehearse thoroughly unfunny but earnestly poignant tropes of modern literary realism? As one might have once imagined Ware himself saying when comparing sensual Art Deco rococo to arid Miesian modernism, “this is progress?”

Ware wasn’t quite a self-made artist, and may not be entirely to blame for disintegrating; he received an early break in Raw from Art Spiegelman (whose dive is only less impressive because of starting lower), but, at the millennium, Ware began networking in earnest with the insufferably ironically sincere elite of the patronizingly-educated-middlebrow culture industry– Dave Eggers, Ira Glass, and Chip Kidd, for starters. His autistic antics in interviews and panels didn’t flag in their ostentatious displays of repression– and in fact, he may have started becoming more of a performance artist (as all celebrities must be) and less of an unequaled craftsman of sequential art. “Twee” describes a current in vulnerable jangly indie-pop music, first British and then American, but came to stand in for the preciousness of a generation that hit on someone by knitting a cozy for their portable toy record player. I think twee killed Chris Ware.

In twee there is neither humor nor horror, neither conviction nor swagger, just feelings. Feelings and nostalgia for feelings. Chris Ware was sucked into this vortex, streamlining himself into a reliable product for easy digestibility by self-styled “nerds” everywhere, and so we ended up with emo comics garbage overflowing the microcosm of craft-fair entrepreneurship and spilling into Michel Gondry, Death Cab for Cutie, and overdetermined bangs (all much to Chris Ware’s chagrin, if he has any left). True, this infantile regression might have happened anyway. Maybe it was September 11th that whetted the American appetite for saccharine melancholia, but I blame Chris Ware. What twee had to offer that was positive– androgyny, sloppiness, magic– was latent but present in his flamboyant early work. He could have made different choices, But it is lost now, lost irrevocably in the sterile, commercially lubricated navel into which his vision has apparently gone to die.

illustration by Bert Stabler

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.