As somebody who didn’t get reacquainted with comics until six or seven years ago I came pretty late to Dave Sim’s Cerebus series. It might have been old news for everybody else by then but it was new to me.

The best part of twenty years previously, I had dismissed my once beloved Asterix albums (plus the illicit stash of Commando digests that I had so painstakingly acquired and smuggled past the watchful eye of my decidedly anti-militaristic mother) as the stuff of childhood and exiled them to the attic.

I hadn’t entirely lost touch with comics since then – I’d borrowed Maus and Watchmen at some point, I’d acquired a handful of old Gilbert Shelton undergrounds and a set of Ben Edlund’s The Tick somewhere along the way, and I was vaguely aware of a few of the alternative comics that were around – but they weren’t really something I thought about a lot or sought out. I had a whole bunch of other things to spend my time and money on.

At least, that is, until the fateful day came that, poking around in the dusty corners of a second hand bookshop for something different to read, I found a pile of cheap, old, graphic novels and decided to buy a few of them on a whim. The three books I picked up that day were an old Love & Rockets collection (Music For Mechanics), the first (and only) colourised volume of Akira that Mandarin published in the UK and the second of Sim’s Cerebus “phonebooks” – High Society. I was blown away by all three. In fact, I was so impressed that I’ve been reading comics and reading about comics and filling up my house with comics and boring other people to tears talking about comics ever since.

That copy of Music For Mechanics prompted me to throw myself into thirty years worth of Love & Rockets collections and that messed about with edition of Akira ensured I’d go on to pick up all of Otomo’s work in English and then lament that there wasn’t more of it to adore.

My love affair with Cerebus, on the other hand, was rather shorter in duration. I picked up a few more volumes – everything from High Society to Melmoth, I think – and it was still pretty good. I don’t think I enjoyed any of them as much as the first I read but I never stopped appreciating Sim’s technical abilities and I was set on working my way through the lot. Gradually, though, looking for info on the internet and perusing old mildewed copies of The Comics Journal and picking up on things on message boards and whatnot, I was confronted with, well, with Dave Sim. Intrigued, I investigated further.

Oh dear.

I didn’t really want to give Sim my money anymore. And I didn’t really want to read Cerebus any further – didn’t want to sully the memory of that first eye-opening, rainy weekend, curled up in front of the fire next to my precious stack of used bookshop finds with the knowledge of the misogyny and homophobia and religious obscurantism that I now knew followed those earlier volumes.

So I forgot about Cerebus and got on with trying (with varying degrees of success) to filter a century’s worth of comic book treasure from a century’s worth of comic book dross.

A few years later, however, I heard about Judenhass and decided to give Sim another chance. I wanted to see how Sim’s art had changed since midway through Cerebus and how it would work in a non-fiction context and I guessed its subject – anti-Semitism – was such that Sim’s more…outré…ideas wouldn’t be likely to get a chance to present themselves. Also, the nice man at the comic shop said it was awesome.

Sadly, the nice man at the comic shop was wrong and Judenhass turned out to be a well meant but bizarrely misconceived work that disappointed on pretty much every level.

Sim opens by telling us that many of the most important figures in the history of comics have been Jewish and that, consequently, it’s particularly incumbent upon creators in the comics field to remember and record the Holocaust.

He’s right, of course, that many of the great names in comics – or at least American comics, which I think, to Sim, are the only ones that matter – were Jewish and he emphasises the point with a page given over to portraits of Will Eisner, Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and various of their peers along with a reminder that “but for geographic happenstance and the grace of God”, those men could just have easily been the ones in the gas chambers.

There seem to me to be a couple of problems with this. The first is simply that by framing his work in such a way, Sim seems to be limiting the target demographic of his work to those mostly middle-aged superhero comic fans who are immersed in the history of the form. It’s hard to imagine Palestine or Persepolis, let alone Maus, reaching so wide an audience as they did if they had they set out to appeal specifically to the mylar and backing board brigade.

The second problem is that the idea that people involved in a field in which Jews have traditionally prospered are the ones who need to be particularly aware of anti-Semitism seems to me to be a little counter-intuitive. I’m not saying that comic creators shouldn’t cover the Holocaust, of course – and there are a number who have done so over the years – I’m just not quite sure why it should be more important that cartoonists do so as opposed to artists working in any other medium.

Moving on, Sim tells us that the victims of the Holocaust included non-Jews but that we must, nonetheless, not fall into the trap of seeing it as anything other than an exclusively Jewish issue.

Indeed, he writes that attempting to embrace the other groups that suffered in the death camps under the Holocaust banner “points to a central and malignant evasiveness on the part of non-Jews”.

Are the Third Reich’s other victims any less deserving of remembrance? And does remembering them make the horror of what happened to Europe’s Jews any the less shocking? Doesn’t what has happened since 1945 in Cambodia and Rwanda and Bosnia and, dare I say, Israeli-occupied Lebanon indicate that “never again” should not be a phrase exclusive to Jews?

Having laid down his condemnation of those who would embrace non-Jewish victims, Sim chooses not to answer any of these questions – one is merely left with the impression that anything other than absolute exclusivity in victimhood would, in and of itself, be anti-Semitic.

It doesn’t seem to occur to Sim that there are Jews who are more willing to reach out to those fellow sufferers than Sim himself is. Just as the anti-Semites damn the Jews en masse, Sim defends them en masse – there is never any indication that we are talking about a diverse group of individuals with divergent opinions, beliefs and attitudes, some of which may not line up with his own.

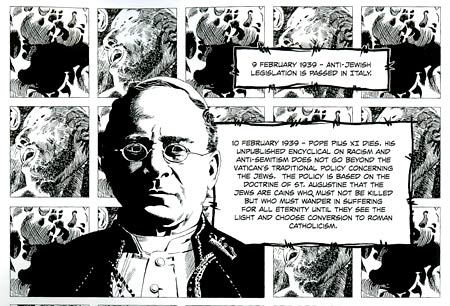

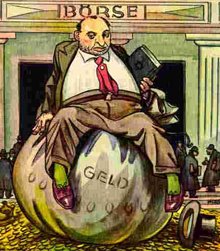

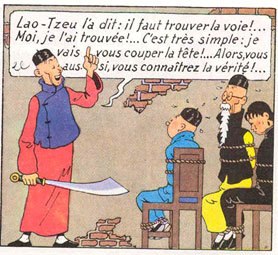

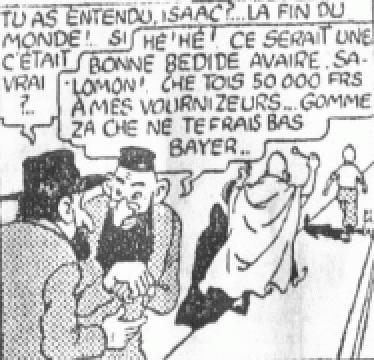

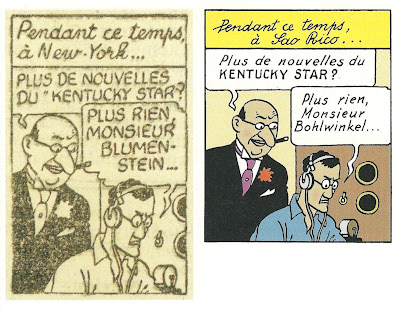

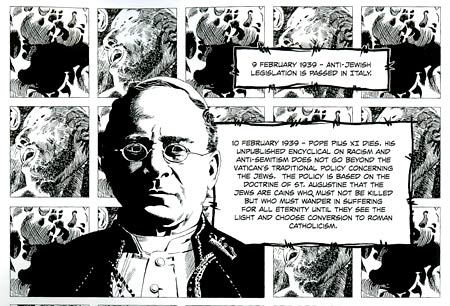

Following the introductory pages the bulk of the book consists of text boxes over backgrounds comprised of drawings painstakingly but counter-productively traced from Holocaust photographs (sometimes accompanied by rather stiff head and shoulders portraits from Sim’s rogue’s gallery of prominent anti-Semites).

I say “counter productively” because Sim’s drawings lack the impact of the photos they’re taken from. Those photographs never cease to draw a visceral response, no matter how many times you’ve seen them. They are truly horrifying, truly moving, each and every time. I didn’t get that reaction from this artist’s rendition. There’s some very well done composition, some effective use of repetition but the images themselves don’t provoke as they should. Rather than trusting to his considerable skills as a cartoonist Sim seems to be on a quest for absolute accuracy (“photo realism”, in his words) but that obsession has robbed his panels of life and the familiarity that most readers will have with Sim’s reference materials only emphasises the difference. The relentlessness of the imagery – the vast majority of the work is an endless succession of tangled piles of corpses and walking skeletons – goes some way towards compensating but ultimately it feels like Sim is trying desperately to pummel his own (obviously heartfelt) emotional response to the imagery into your skull. Repeatedly.

So, what of the contents of those text boxes accompanying the art? After a few pages of anti-Semitic phrases and sayings taken from various languages at various times, Sim devotes the rest of the work to a chronological series of quotes and historical events from around the world, ranging from 70BC to 2007. By this point, though, he’s only left himself 28 pages to work with (excluding the end notes) – this is a very slim volume for such a big subject – and there’s very little text per page. The result is that we get next to nothing in terms of context. There’s no explanation of the roots of anti-Semitism, no exploration of how it was harnessed and promoted by the Church, no information given on where insidious myths about Jews originated from or how they developed, nothing about how the treatment of Jews has compared and contrasted with that of other religious and ethnic minorities through history, nothing about the ups and downs of the pre-Israel relationship between Judaism and Islam. It’s all incredibly lightweight.

As with the art, the quotes resemble the drip-drip-drip approach of the Chinese water torturer and just as the art makes you think you’d be better off looking at photographs, the text makes you wish you were reading a prose book on the subject – something with a bit of heft to it, something with a bit of depth.

Uncomfortably (for me at least), as the quotations enter the 20th Century, Sim begins to sometimes conflate Zionism with Judaism (or, more particularly, anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism). I don’t think it ever occurred to him that there might be objections to the concept of Zionism, or to the state of Israel and its actions, that aren’t rooted in hatred of Jews (let alone that Jews themselves might hold those objections).

Indeed, one of the last quotations he offers up, entirely out of context, originates from an anti-racist campaigner and academic arguing not against Jews but rather in favour of an academic boycott of Israeli universities in protest over Israeli breaches of international law. How is that anti-Semitism?

Sim devotes about as large a portion of the text to President Truman’s procrastination over the establishment of Israel as he does to the Final Solution, which seems a strange weighting.

His position seems to be that Truman’s initial resistance to the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine was anti-Semitism pure and simple and that the eventual reversal of his position was him finally seeing the light. Sim himself seems unsure as to whether or not the words he puts in Truman’s mouth belong there or not, writing in the end notes that he found a key passage “suspect” but decided to use it anyway, the better to make his point.

In any case, the reader is left in little doubt that the foundation of Israel was right and proper and that any that argued otherwise – or protest its actions today – belong, incontestably, to the same line of thinking that gave us Auschwitz. Moreover, the impression given is that Israel was Truman’s to found or not found, as simple as turning a light switch on or off – nothing is said of the reservations of the British government then running the Palestinian protectorate, let alone of the Palestinians themselves.

In his end notes, Sim expresses his wish that Judenhass be used in schools as teaching material. Sadly, I don’t think it’s remotely fit for the purpose. Sim claims school children “in this age of diminishing attention spans” aren’t capable of concentrating for more than the 25 minutes he thinks it would take them to read his book. But what academic use is a scattergun assemblage of quotations without context or elaboration? What use in the modern world is a book for a general teenage audience that attempts to suck the reader in emotionally with the presumption that all kids not only read superhero comics but also know (and care) who created them 60 or 70 years ago?

Moreover, putting its other problems aside, speaking as somebody who lives and works in an inner city area where a substantial proportion of the population is made up of first and second generation Muslim immigrants, I really don’t think I could reasonably recommend this book to any of the local teachers or school librarians I come into contact with (despite the fact that some of the Muslim kids they teach are the only people I ever hear bandying about anti-Semitic remarks and so should, in theory, be just the people to benefit from it). In order to begin to tackle the prejudices so many of those kids were raised with, they need a book that teaches them that “Jew” and “Israeli” are not synonymous, not one that encourages them to think that they are.

I’m grateful to Sim – along with los bros Hernandez and Katsuhiro Otomo – for bringing comics back into my life. But if Judenhass and the brief preview of Glamourpuss I saw when it was first getting started are any indication, I’m rather afraid that the quality of his comics output has now descended to the same level as that of his philosophising.

So I’m afraid it’s a case of “so long, Dave – it was fun to begin with but now I think we should see other people”. And this time I mean it.