I notice the air getting very thin when I’m in a discussion with cartoonist peers and the subject of furries is brought up (oftentimes by myself and my friend, the glass of wine), filling the vacant atmosphere like a silent fart. To the sub-culturally literate who know and love to hate us, we are mad, shallow tacky perverts; aesthetically handicapped loser-kin often more adept at creating elaborate webs of internet drama than art, stories or comics of any value to people outside of the fandom. This is a half-truth.

There are artists working within and at the margins of the furry subculture producing spectacularly daring, inventive, funny, hyper-aware fiction who nevertheless feel deeply insecure about associations with such a maliciously misunderstood subculture. There aren’t many works in the canon of respectable comics which feature anthropomorphism in furry style ™. Instead of majestic, inventive comics like Krazy Kat, furry style was initially shaped (as an offshoot of science-fiction fandom in the early 80s) by admiration for Disney cartoons (Robin Hood, woof!) and advertising mascots. Our foundational sensibility is gene-spliced super-soldier pulp paperbacks, Tex Avery and the naïve dom/sub sexuality of old Fox and Crow funnybook covers. And those comics suuuuuuuuuuuucked. Sucked the paint off a barn. The vicious aside about funny animal comics near the end of Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay stings all the more bitterly because woe, it is so so true.

So we furrs pounce when a sophisticated mass-market comic featuring talking animal-people gets a little, or a lot of love from readership and critics. The Blacksad series by the team of writer Juan Diaz Canales and illustrator Guarnido might be the holy grail of furry respectability within the world of comics. The stories utilize a cast of upright-walking humanoid animals that exist within a model of human behavior, yet their individual animal speciation informs their human-like character and personalities. These are conceits that furries can claim as their own, regardless of actual authorial involvement in the subculture. (This applies retroactively to previous iterations of pop-anthropomorphism as well —but let’s not get sidetracked.) Blacksad has cred, it’s popular, and it’s very furry. It’s also very troubling if it’s the type of material that we’re going to hold up as a standard of excellence for anthro comics with a broader market appeal than furaffinity.net.

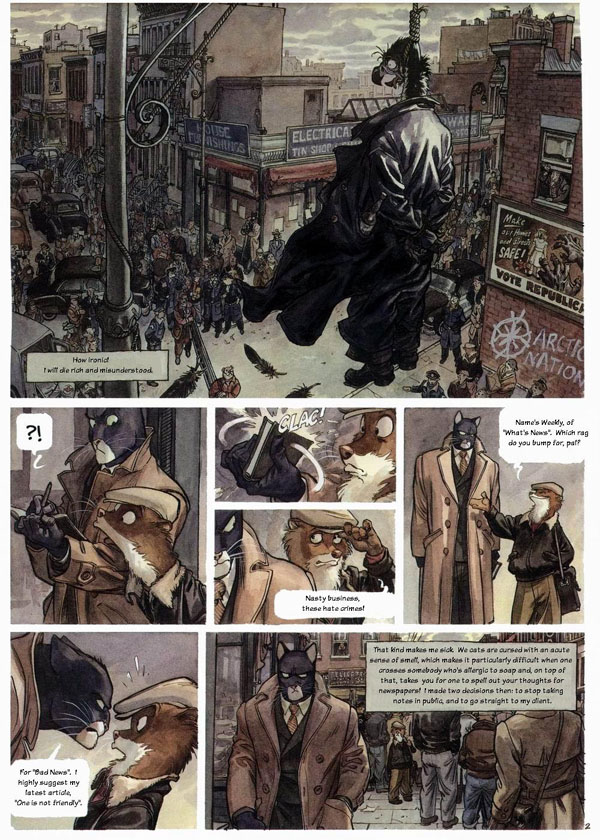

Blacksad has been recently reprinted in hardcover, bundled with the unreleased -en Anglaise- Ame Rouge, by Darkhorse as well as a second volume of new material which I have not yet read. The previously released second volume, Arctic Nation, won a Harvey award in 2005. It thrusts our hero, the titular John Blacksad, into an intrigue set against an atmosphere of mid-century racist tension and violence outside New York City. Rather than a sober European critique of American racism and class struggle (haha let’s not trouble ourselves with that thought), Arctic Nation is unfiltered, earnest pulp. It begins, subtle as an asteroid collision in your nana’s parlour, with a lynching. On page 2.

Backing up a bit. I can’t offer much in the way of relevent analysis or anything new to say about racism, or depictions of racism in comics per se. I don’t have a seat at that table. Furthermore, the Blacksad universe is very clearly meant to represent a pulped version of reality, and it’s up to discussion whether fiction in this vein should be judged according to its reflection on political reality or read on the terms of the self-contained universe of its creators’ imagining. But the animals Guarnido populates the world with are meant to suggest inferences about human traits, including racial ones. And I do feel, as a furry, like I have something to say about their use in Arctic Nation (or the use of various species to represent different ethnicities and nationalities of human beings in the first place. Hint: it’s a really bad idea!).

The second volume in the Blacksad story follows our hero John, the taciturn tom-chat noir private eye, on an assignment into a suburb called the Line, which is in a state of social upheaval following the decline of its post-war manufacturing boom. The world, entirely populated by a managerie of anthopomorphic animals, expands in complexity here. A coalition of animals of various species who share in common their white fur, many of whom occupy ossified posts of old social power has hardened into a hard-right group -a mixture of the Ku Klux Klan at the height of its influence and the American Nazi Party of the 60s and 70s- that overtly terrorizes everyone else. The only organized resistance, the “Black Claws” — an obvious parody of the Black Panthers — is cast as equivalent in their odiousness to the white hate group.

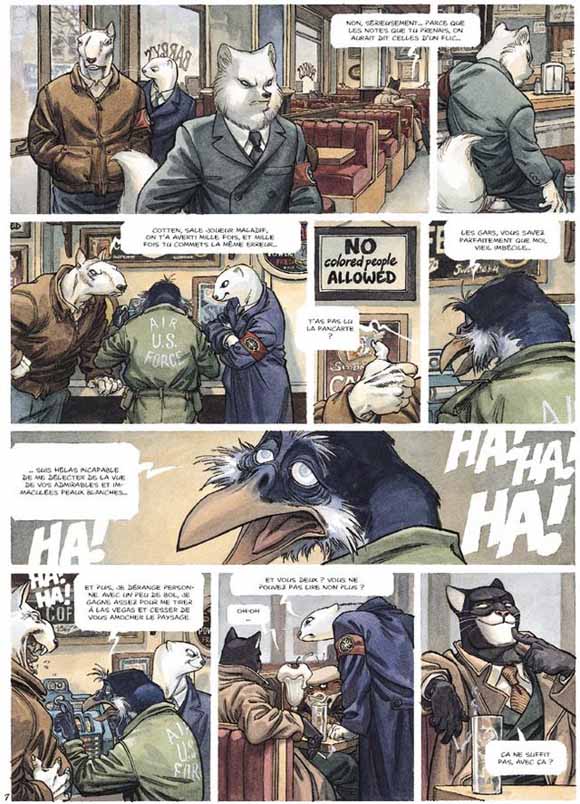

This brings up an interesting point that is not readily apparent in the first volume of Blacksad. John, a black-furred cat, is in terms of a human analog, a black man, and is treated as such — but with a caveat. He has a patch of white fur on his muzzle which affords him some access to interactions with the white-furred power brokers within the neighborhood. This concept of his “whiteness” is directly alluded to on page 9 of the iBooks paperback printing when he is hassled by Arctic Nation thugs in a diner that conspicuously displays a notice that reads “NO colored people ALLOWED.” He rolls his eyes and offers a deliciously smug, self-confident grin. “This here isn’t enough?” The initial victim of the AN goons’ attention, an old blind crow wearing a US Air Force Jacket, a possible nod to the Tuskegee Airmen, isn’t so lucky. He also has white facial markings but they are signs of age, and without John’s gift of brute strength (applied with gusto in the following page) he is an easier target.

One of the most interesting characters in the story, for many reasons, is Weekly, the sidekick and comic relief to John’s turgidly upright straight man act. An unctuous tawny-furred mustelid, Weekly reads as white but is unsympathetic to the Arctic Nation’s fanatical racial vision. He is a target of scorn by the white-furred citizens of the Line, though this could be attributed to his unsavory profession as a weasely tabloid reporter or his “European” approach to hygiene (his nickname stems from the supposed infrequency of his change of undergarments). His exclusion from the ivory racist clique also exempts him from the system of oppression against black-furred animals in the Line. He is familiar, actually chummy, with our hero from their first interaction. The only system of oppression in Blacksad’s universe is at the hands of a white nationalist extremist population which has the means to mobilize against a specifically black one. Red or brown or orange fur occupies a “neutral” territory.

John is on a case of a missing child whose mother is reticent to report her disappearance. John is working on behalf of the girl’s concerned teacher, Ms. Grey (symbolism!). The “plot” that transpires hurls him neck-deep into a preposterous, Oedipally-fraught revenge scenario whose architecture involves murder, incest, the previously-mentioned abduction and plenty of manipulation through the withholding and dispatching of gratuitous sex. In spite of all this spice, it’s not all that interesting. A polar bear named Karup (wordplay!) falls in love with and marries a deer, but their relationship is poisoned by his lust for power and inclusion in the white-furred elite of the Line. He abandons his pregnant bride to die in a snowstorm (symbolism!) and goes on to become chief of Police. She survives and gives birth to two fraternal “twin” daughters, a white-furred polar bear and a vampy, heavily caricatured black deer (more symbolism! nonsensical biology!), but separated from her husband’s love, she wastes away into alcoholism. (An aside: if the case were to be made for Arctic Nation being in fact a hideous racist publication, the panel where we are made to leer at the deer’s degradation and death while her daughters stoically look on would be exhibit A. It’s skillful cartooning at its most rotten, twisted, and cruel). Moving on!

Karup’s daughters, now adults, set their revenge against him in motion, Jezebel (a Madonna/Whore cliché, goddamn with the symbolism) marries him, though their relationship is icily chaste. She meanwhile uses her sexual wiles to foment a power struggle within the Arctic Nation. Dinah meanwhile orchestrates the kidnapping of her own daughter to exploit standing rumors of Karup’s perverted predilections and set up a coup for his ambitious subordinate Huk. Just about everyone dies gruesomely, leaving Jezebel with her thin victory to cloak her grief and Blacksad to righteously brood over the twisted nature of the world.

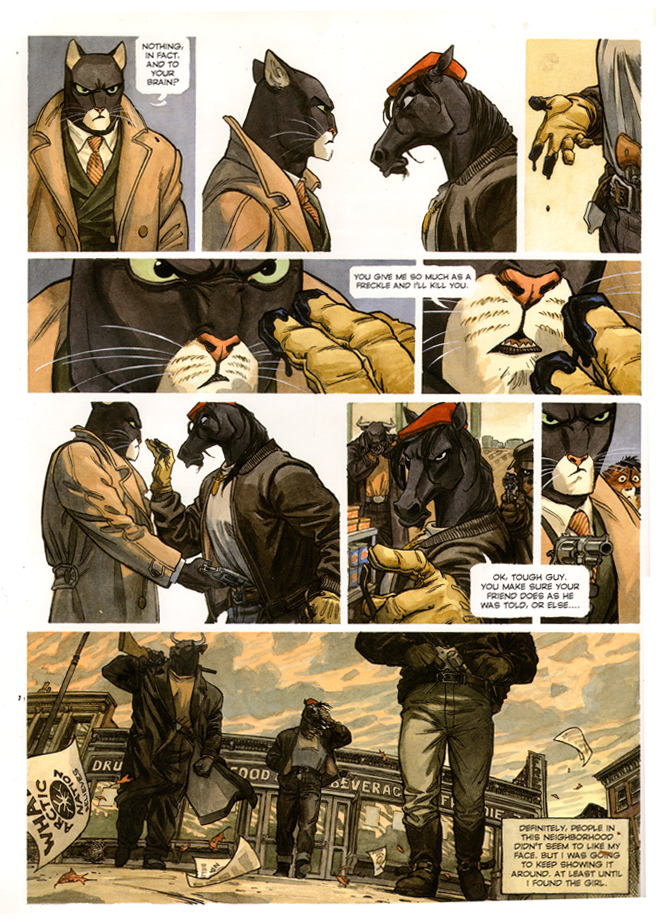

Throughout, John does little actual detecting. He slinks throughout cross-sections of the Line and throws a couple of well-placed elbows when things get hot while the sisters’ plan falls into place on its own. He sneers at the endogenous old blue-bloods, the white tiger Oldsmith and his mentally-handicapped Cheetah son whose only purpose is as a tidy avatar of rebuke. He tussles with a few representative members of the Black Claws, two beasts of burden and a Rottweiler. Acting as a typically crass reduction of black resistance movements, the lead black toothy horse first intimidates Weekly to publish some piece of propaganda and then taunts John for his whiteness. “What happened to your snout, brother?” he asks before attempting to smear the white patch on Blacksad’s muzzle with motor oil. John responds by plugging his revolver into the assailant’s waistline. It’s no accident that this Claw is a horse – what with their prodigious members. You emasculate me, and I’ll emasculate you! Either way, John will have none of your Black Consciousnes, sir. Whiteness unbesmirched, John fumes in the car outside after the claws disappear into the foreground and from the story altogether. “You’re not going to publish that crap, are you?”

I might wonder similarly at Blacksad’s editors. Guarnido employs honed caricature, meticulous detail and a sophisticated color palate in service to a crude and unsophisticated pulp rag that exploits images of American racial and class struggle for cheap moralizing while rendering nothing of any value. Anthropomorphism is a give and take, and often works better when we allow the animal traits (themselves human projections) to reveal character i.e. Sam the Clever Fox or whatnot. Shoehorning human society onto one or several unsuspecting ecosystems and tossing them together in a fantastical New York is simplistic and prone to breakdown. The relationship between the arctic fox and the snowshoe hair is warped beyond any sense within the boundaries of Arctic Nation’s universe. Are they bonded as brothers in attempted domination of the vampire bat, the grizzly bear, nay any creature not possessing white fur, an arbitrary gesture of humanity draped over animal cyphers? We can use funny animals to talk about funny peoples, but my god we can do so much better than this turd.