THANK YOU

First of all, thank you to everyone for taking the time to read, interpret, write about, and discuss Likewise. When I was writing Likewise (age 19, in a windowless basement in Brooklyn) I spent a lot of time fantasizing about people one day analyzing the book. That this is now happening is really exciting.

OVERALL

One issue with Likewise is that it works much better if you’ve read the previous three books in the series. I originally envisioned the series as one 737-page book titled Likewise, Potential for the Definition of Awkward: The High School Chronicles of Ariel Schrag. The series is about the evolution of one person – the developing art and writing over the course of the four books parallels the act of growing up. For this reason, much of Likewise references the other three books.

RESPONSE TO EACH POST

DICK TALK – NOAH

“Ariel thinks about penises the way constipated people think about their bowels. When your bowels are in good shape, they only draw your attention every so often, and otherwise you don’t need to worry about them. If your bowels are off though — well, you focus on them a lot.”

This is a pretty funny and for the most part accurate analogy for the role of penises in Likewise. As we all know, the penis is the focus of sex in society and considered the most important player in the sexual act – there are dildos for lesbians, but no fake vaginas for gay men. Many people (including Ms. Salt!) affirm that dildos are not “penises” – but even if it’s blue and shaped like the Virgin Mary, if you strap it on and fuck someone with it, it’s going to kind of seem like a penis. In Likewise, Ariel is obsessed with the idea that lesbian sex – even though she prefers it – is still missing something. She fears that lesbian sex can never reach the “ideal” that sex with a penis achieves. So yes, she thinks about penises a lot – but more as a frustration object, than a pleasure object.

This theme ties into ideas of masculinity and identity. If you want a penis, but don’t want to be a man, where does that leave you? As Noah writes:

“…That last panel, where she thinks “I’m not a woman” — that’s not a victory. Being taken for a man doesn’t make her a man; it unsexes her. When her phallus is most manifest is when she measures up least.”

Noah writes that more important than Ariel’s desire for “a penis” is her desire for “the phallus.” He equates this idea with the discussion of “It”:

“It, then, is cool; It’s ease with authority; It’s mastery. I think Freud would call it the phallus… Ariel in the comic declares, “My comic has It.”

Art is Ariel’s solution to the phallus problem – it’s her solution to every problem. Which becomes the problem itself. To some extent Art as Phallus works – it’s a place where you have total control and the goal is clear. It’s a way to show off how great you are.

“…far from being constitutionally inadequate, Likewise is, in the way of ambitious art, swaggering. If the book’s about wondering where your dick is, it’s also about pointing down and saying, “check this motherfucker!”…. She demonstrates she has the thing by the skill and humor with which she shows she doesn’t… Creativity, in short, is the biggest, most potent penis of all…”

But art is ultimately outside of yourself – no matter what, it’s still just you at the end of the day. As Likewise continues, the failure of depending on art to solve your life is revealed. As Noah writes:

“…is the distancing of meta; the constant drive to observe and record herself pushing authentic reality away? Or is it working through different ways of holding onto reality — and maybe finding that grasping it a little less firmly makes it easier to hold?

IN SEARCH OF “IT”: A RESPONSE TO A REVIEW OF POTENTIAL – SUAT

Suat begins this post with a summary of the plot of Potential:

“Ariel goes to high school, “discovers” that she is a lesbian, meets other girls and has occasional sex and alcohol.”

Once I read this summary, I couldn’t take much of what Suat had to say seriously, since he hadn’t really read the book.

Noah’s post BATTLE AT THE LIKEWISE ROUNDTABLE sums up my general response.

LIKEWISE DESIRE – CARO and HOW ALIKE IS LIKEWISE – NOAH

Caro: “So she failed at the impossible task of writing a graphic equivalent to Ulysses — but fucking hell she tried, and that’s much more ambition than most graphic novelists show.”

As was concluded in the comments to this post, I wasn’t trying to write the graphic novel equivalent to Ulysses. Ulysses plays a significant, but not overarching role in Likewise. It is both a talisman and an artistic influence. Caro does a great job of describing Ulysses’s role as talisman, noting that it represents both what Ariel finds so appealing about Sally – that Sally read this impressive book as a teen and Ariel’s desire to be like her – as well as Ariel’s relationship to her comic – her desire to create a Great Work of Art like Ulysses.

As an artistic influence, Ulysses inspired various techniques in Likewise: complex structure and order, significant use of certain words and numbers, stream-of-consciousness narration, employment of unique styles to represent different modes of reality, emphasis on graphic sexual and scatalogical content, and literary allusion.

Caro: “(Parts 2 and 3) prioritize grafting Schrag’s narrative onto the structure of Ulysses and are more Baudrillardian: she tries to follow the contours of Ulysses and ends up creating something that is not-quite-a-simulacrum but that certainly aims there.”

The use of different styles in Parts 2 and 3 of Likewise is inspired by Ulysses, but the goal was not to create a simulacrum. Similarly, while there are some allusions to other books and comics (Madame Bovary, The Brothers Karamazov and Maus, primarily), these references are not central to Likewise the way literary allusion is to Ulysses. Ulysses was an inspiration, and Likewise is in some ways an homage – but it is not a simulacrum. Rather, just as Ulysses is a simulacrum of The Odyssey, Parts 1, 2 and 3 of Likewise are simulacrums of Potential, Definition, and Awkward, respectively. Creating simulacrums of your own books is, I know, completely self-obsessed and claustrophobic – but that pretty much sums up being an 18-year-old.

As a high school senior, the creation of the comic series and the identity that had given me had taken over my life. Creating simulacrums of Awkward, Definition and Potential in Likewise, was one way of expressing that.

In the latter half of DICK TALK, Noah points out many of the ways in which Parts 2 and 3 of Likewise mirror Definition and Awkward. Jason Thompson does this as well in ARIEL SCHRAG, SUBJECT AND OBJECT.

In the Comments, Caro writes:

“But I do tend to think that’s not uncharacteristic of juvenalia: here you are, writing along, working on the autobiography you started when you were 15, and suddenly you have a Big Idea. So you crowbar it into the project you’re already working on, rather than recognizing that it’s its own thing. And then you end up with a single book that’s really two books, and the two books compete against each other. The autobiography part of this could have been much shorter and more focused on interesting episodes, and the Ulysses part could have been much more successful if it didn’t have to mesh with the life story.”

I disagree with this. The idea with Likewise was to mesh teenage autobiography with a book like Ulysses – that’s specifically what I found interesting and novel. I liked the idea of fusing highbrow and lowbrow – a modernism-inspired book confined to the content of one year in the life of a teenage girl. This fusing of highbrow and lowbrow, of mature and immature, is what appealed to me about comics to begin with. Comics were barely a respected art form when I started writing, and I loved the idea of taking a “for kids” medium to write adult (sexually graphic, complex emotions) content.

Noah writes:

“I actually like the way the book both fetishizes modernism and distances it through various techniques (the very lowbrow reliance on diary; the DIY art, parody.)”

The following from Noah in DICK TALK relates to this:

“In this sequence, Ariel’s reading Ulysses, and she comes to a section where Joyce describes a penis… The best bit here, though, is not the visionary penis, but rather the vision itself. The wobbly panel borders above are not just filligree; they’re there because Ariel’s stoned. Her paean to Joyce’s penis can partially be read as “Joyce — he is a genius, and I appreciate him.” But it can also be read as, “Wow—like— everything’s really meaningful when you’re stoned, dude.” Literary critics singing modernism’s hosannahs are deftly equated with gently tripping potheads.”

Likewise is about being aware that you’re a teenager – knowing there’s something ridiculous about yourself. The self-obsession, the sex obsession, the obsession with being cool… these things are with you your whole life – but never as strong as when you’re a teen. You know you’re taking yourself way too seriously, but you just can’t stop.

In the comments, Caro writes:

“Looking back, it’s striking to me that the “father of thousands” scene Noah referenced is almost exactly the half-way point in the book and really marks this shift from her interest in actually existing penises (and phalluses) to the more aesthetized “phallus” of her artistic ambitions. That’s what the different drawing meant to me there: “here is the moment where Art becomes a theme.””

This is true. Shortly after this scene is the first instance of Art usurping Life. On page 221 Ariel is having an emotional breakdown in the car with Sally when Ariel’s stream-of-consciousness narration transforms into a past-tense typed story on the computer. The visual cuts from Ariel and Sally in the car, to the future Ariel typing at the computer. Ariel is saved from this painful event by existing only in the artistic recreation of it. At this point in the book the different methods of recording start taking over the storytelling.

ON TEENAGE FETISHISM

Caro writes: “But by the time you’re 30, if you’re still fetishing teenage screams, you’ve got a problem (and there are a lot more ways in which this is a problem than actually destructive pedophilia). The problem isn’t the teenagers — they’re age-appropriate. The problem is middle-aged people who are still fascinated by adolescent things at the expense of grown-up things.”

I disagree with this. What I love about teenagers and literature or movies about teenagers, is that everything is so extreme. As adults we all still experience many of the same emotions, but because we’re not having them for the first time, they aren’t paid as much mind, or we’re more ashamed of them, or we deal with them in more responsible and practical and well… boring ways. No one should act like a teenager as an adult, but I don’t think it’s wrong to have a fascination – I think that fascination is with your inner self.

ARIEL SCHRAG, SUBJECT AND OBJECT – JASON THOMPSON

I really enjoyed Jason’s post on reading autobiography with an interest in the author as a person as well as a character. It’s how I read autobiography too, and the author is definitely asking for that on some level.

This post is especially important in how it relates to Ariel’s character in Likewise.

The fascination I experienced people having with me as a teenage autobiographical cartoonist strongly effected my sense of identity – and that is one of the primary themes in Likewise. The comics made people like me, pay attention to me, treat me as someone special – and that attention was addictive. The comics became the most important part of who I was – and it’s always dangerous to have one thing define you.

Jason also writes about comparing the different books in the series to each other:

“It’s the same reaction made by many people within Likewise itself, who are disappointed by the clinical nature of Potential… compared to the exuberance of Definition. To dismiss Likewise for not being Definition is to dismiss Schrag for growing up.”

I appreciate this comment. It always bothers me when I read a review that wishes Likewise was more like Potential, or Potential more like Definition. The books are about someone growing up and exploring all the different parts of being human. To me, Awkward is the most pure, Definition is the most funny, Potential is the most emotional and Likewise is the most intellectual. You may prefer one to the other, but they are all parts of yourself.

NOT JAMES: Y-FRONTS, DICKS, AND DYKES – VOM MARLOWE

“…when one is commenting on a persecuted group, especially when dealing with identity, it’s worth knowing how a person stands: with, against, or where. So I’m not straight and I’m female, and there you have it.”

Vom Marlowe’s decision to refer to herself as “not straight” rather than “gay” or “lesbian” or “bisexual” or “queer” is intriguing. Often (and this is not necessarily true of Vom Marlowe) when women define themselves as “not straight,” it means they at one point slept with women, but are now with a man. Personally, although the “lesbian identity” has had its benefits for me – getting lots of girls, getting to write on a hit TV show – I’m pretty anti-label. I think queerness should be visible and celebrated as part of human diversity, but I also think sexuality is, for everyone – albeit in different ways – ultimately fluid. And labels and fluidity just don’t match up.

“Except she has the same problem I do, ie, hips much bigger than the waist, which means that the damn jeans hang oddly. (This is why I am in love with certain hip-curvy jeans that came out after Likewise was released.)”

This cracked me up. The low-rise jeans made with 1% spandex that first made an appearance in the early 2000’s are a HUGE improvement on the hips/jeans problem. I often wonder if this section of Likewise won’t resonate with later audiences who take these new jeans for granted.

“…it’s not just Ariel’s sexual identity in question, but her sexual identity in relation with others, especially Sally.”

Much of the gender confusion in Likewise has to do with being in love with a (mostly) straight girl. It’s always fascinated me how a person’s gender representation changes depending on who they are dating. For me, I think there is an inherent “butchness” inside me – something that’s been there since I was a kid – but the degree of that butchness has varied drastically over the course of my life, and often depends on the particular chemistry I have with another person.

“When Ariel goes home, she looks in the mirror, popping zits, and is comfortable with what she sees there. The regular clothes, the regular face. It’s not a collection of stressed voices recorded from other people, but her own perspective, her own art, her own voice… I am arguing, that she tried being what Sally liked: played at being more of a man, played at comic-creating more like Joyce, but she decided instead to be who she is…”

Much of this analysis is true, but the last page of the book is more about Ariel’s freedom from the comic than anything else. After the batting back and forth between different recording styles in Part 3, the last page of Likewise ends with the style from Part 1 – the present day, stream-of-consciousness narration. Senior year is over and Ariel finally doesn’t have to keep recording her life for everyone to read. For the first time, in a long time, she experiences a private moment.

GENERAL QUESTIONS:

CARO QUESTION:

“You know — I really wanted to understand what was going on with the occasionally absent facial features and I haven’t gotten that worked out yet. Any tips?”

NOAH: I think it’s an attention thing in part; folks who Ariel’s not concentrating on tend to shift into anonymity.

This is right. I didn’t want to draw attention – although it often seems to draw more attention! I inked the expressions just as I had drawn them in my rough sketch, and if I didn’t draw the mouth or eyes in the rough, I didn’t consider them necessary.

DAVID QUESTION:

I’m especially curious to see what Schrag thinks she would do differently were she moved to recreate the story of her senior year now, a decade later.

I would not be moved to do this. For one thing, I’m not interested in autobiographical confession and exhibitionism in the same way anymore. The main reason I wouldn’t rewrite this book, though, is that it would go against the idea of the book itself. As I said earlier, the idea behind the high school comic chronicles is the evolution of a character. Many parts of Likewise make me cringe and the writing and drawing could certainly be better, but it needed to be written by a 19-year-old. I didn’t change anything as I inked it over the past decade, as much as I saw room for improvement. The purity of a “real-time” chronicle was the most important thing.

LIKEWISE TECHNIQUE BREAKDOWN

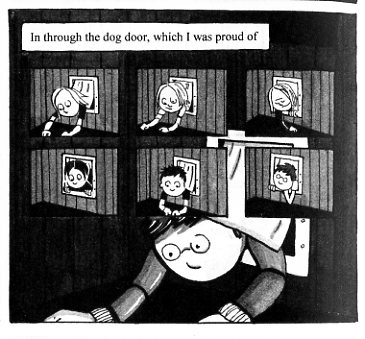

For those who are interested, here is a breakdown of the stylistic shifts in Likewise. While much in Likewise is subtle, these shifts were meant to be obvious, and I think it’s a failing of the book that from what I’ve gathered, most people don’t recognize them. So while I generally don’t believe in over-explaining one’s own book, here it is:

Stylistic shifts in Likewise:

Present Day:

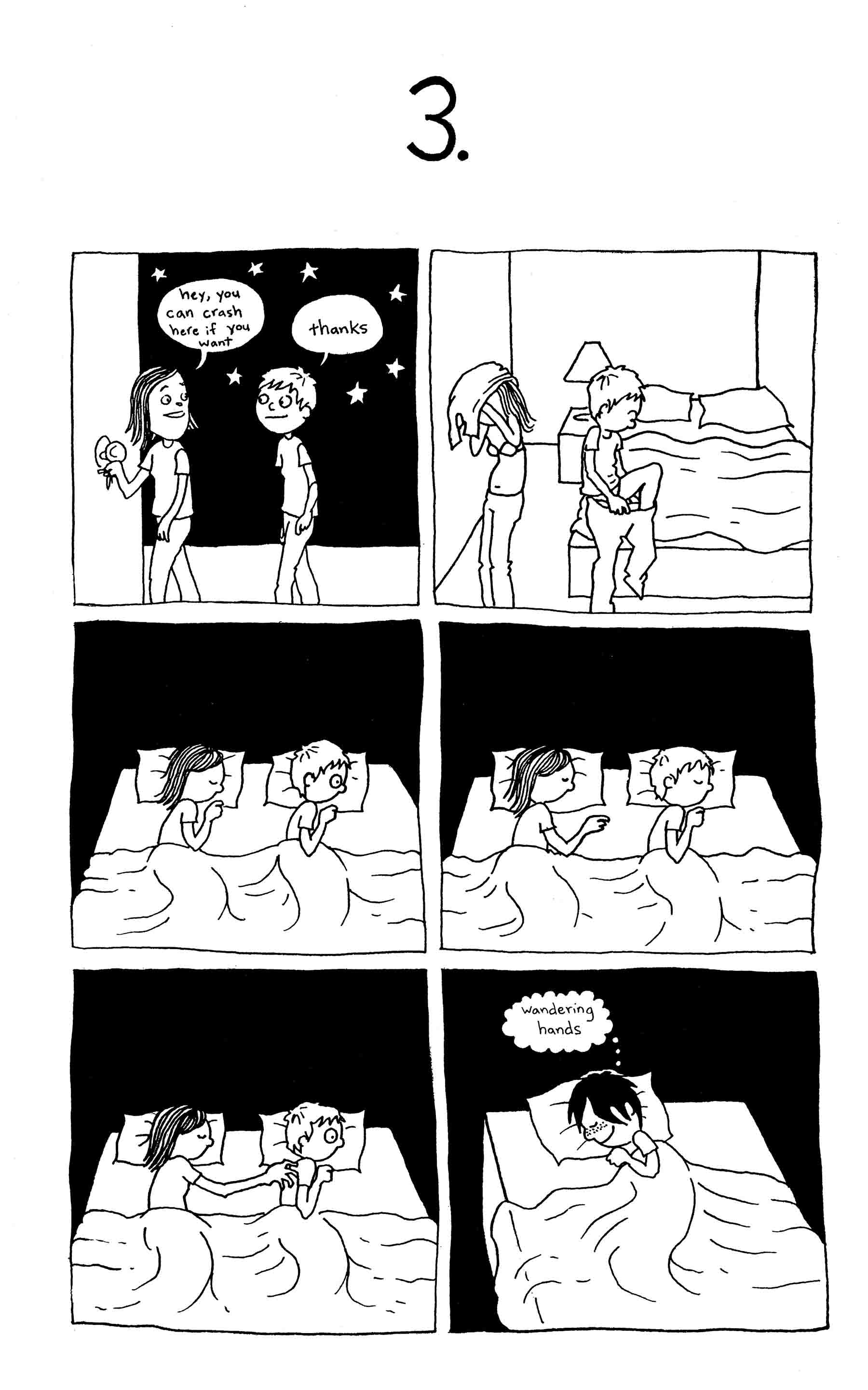

Drawing style: Black and white with cross-hatching.

Storytelling style: Present tense stream-of-consciousness narration. Dialogue.

Flashbacks (past events in which Ariel was present):

Drawing style: Computer gray tone. No solid black.

Storytelling style: Dialogue and Ariel’s thought bubbles.

Imagination (imaginary scenarios or past events in which Ariel was not present):

Drawing style: Hand drawn stippling. No solid black.

Storytelling style: Sparse Dialogue.

Present Day in which Sally is present

Drawing style: same as Present Day, except without panel borders.

Storytelling style: same as Present Day

Typed Computer records

Drawing style: Ink wash and solid black.

Storytelling style: Typed first-person present and past tense narration. Dialogue.

Handwritten Journal records

Drawing style: Unfinished sketches.

Storytelling style: Journal excerpts on notebook paper. Dialogue.

Tape-recorded Audio records

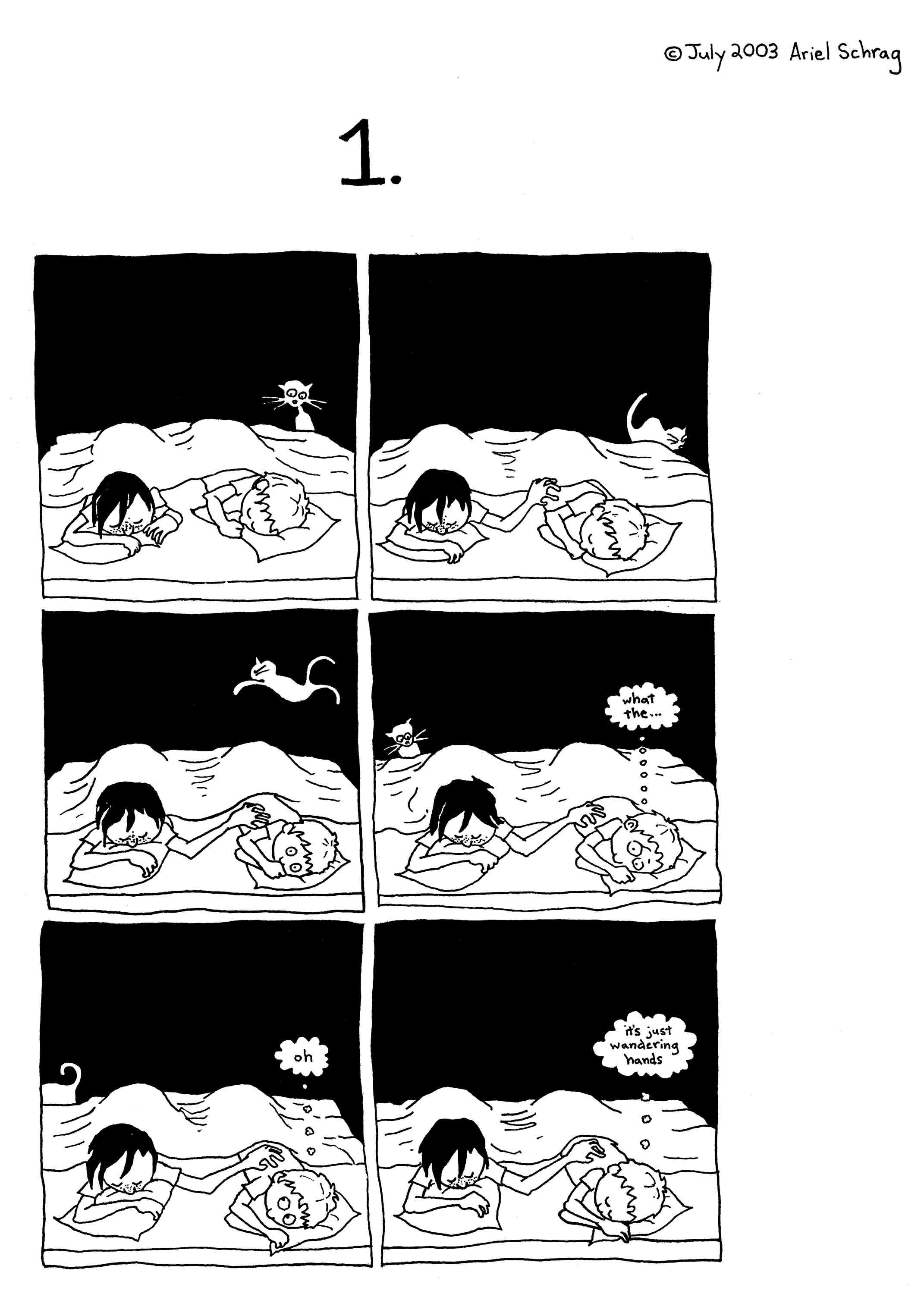

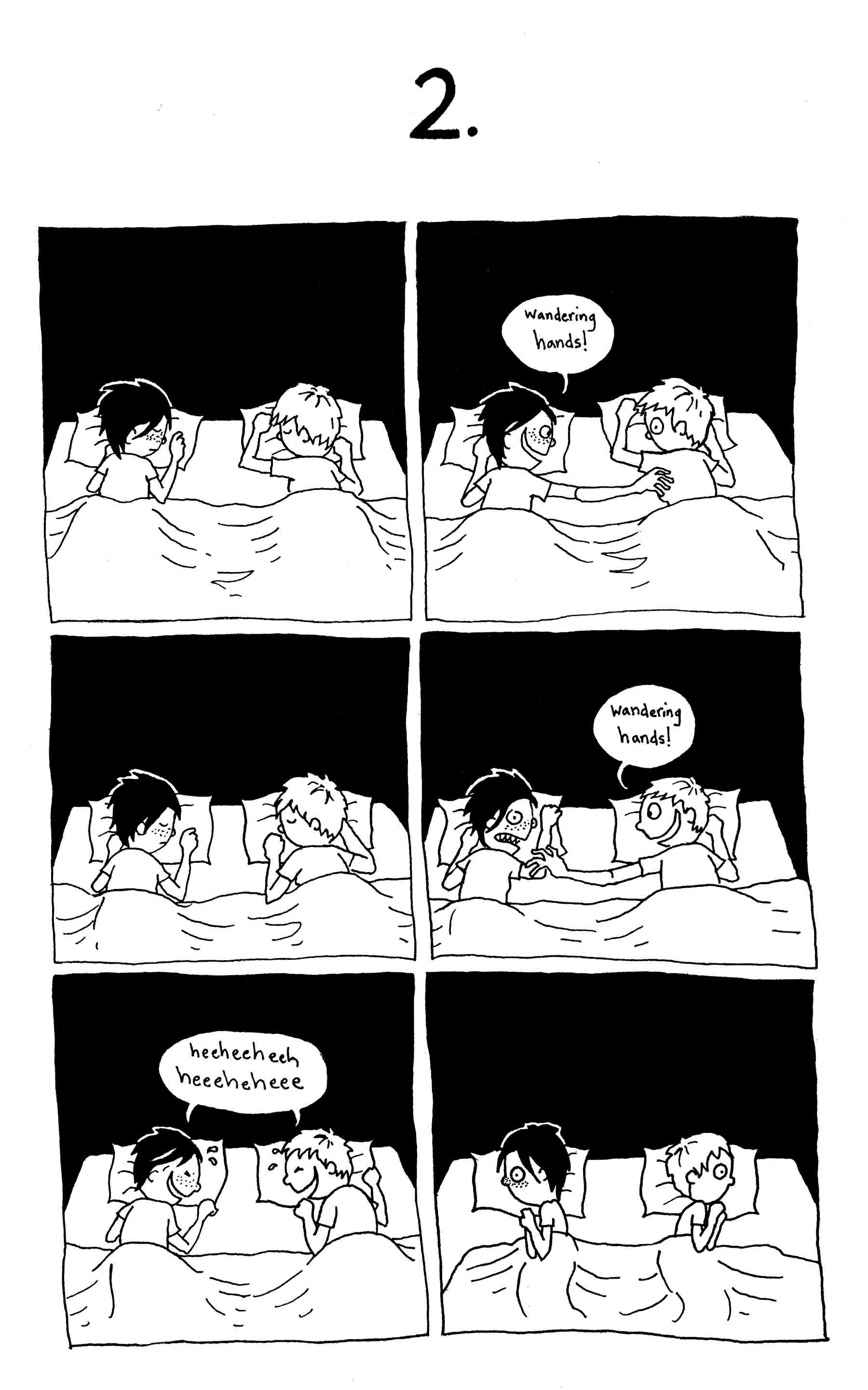

Drawing Style: Heavy black and white on a black background.

Storytelling style: Tape-recorded dialogue.

_______

Update by Noah: The whole Likewise roundtable is here.