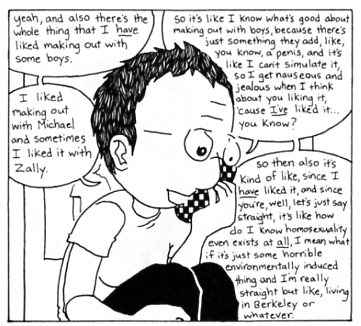

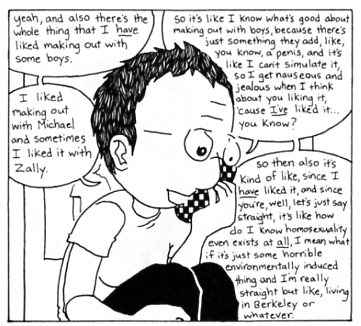

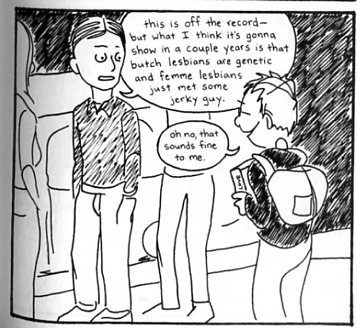

For a memoir about a lesbian coming of age, Likewise is absolutely full to bursting with penises. There are Schrodinger’s penises attached to various possible boys who may or may not be fucking Ariel’s not-nearly-gay-enough ex Sally. There’s a much touted artificial penis which Ariel purchases on her eighteenth birthday. There are daydream penises, which keep intruding, somewhat queasily, into Ariel’s masturbatory fantasies. And there are even some real live honest to goodness actual penises attached to guys with whom Ariel does assorted non-lesbian type things.

In short, to get all alliterative, the penis-to-panel proportion is patently preposterous. Even the most drooling male sybarite fueled by the most unforgiving mid-life crisis (Kingsley Amis, say, or Dan Clowes) couldn’t have conceived that teen lesbians were this obsessed with male genitalia. I mean, really, it’s difficult to imagine that straight women think about it that much.

Which is sort of the point. Ariel thinks about penises the way constipated people think about their bowels. When your bowels are in good shape, they only draw your attention every so often, and otherwise you don’t need to worry about them. If your bowels are off though — well, you focus on them a lot.

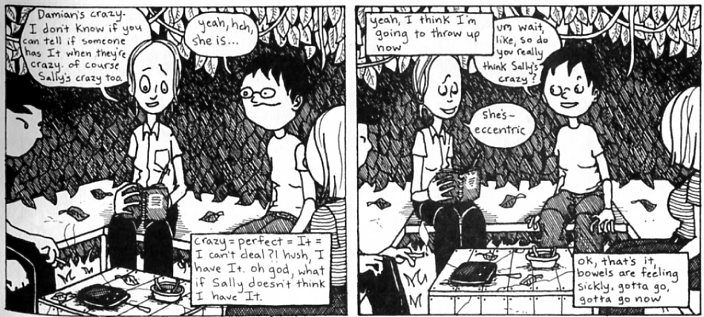

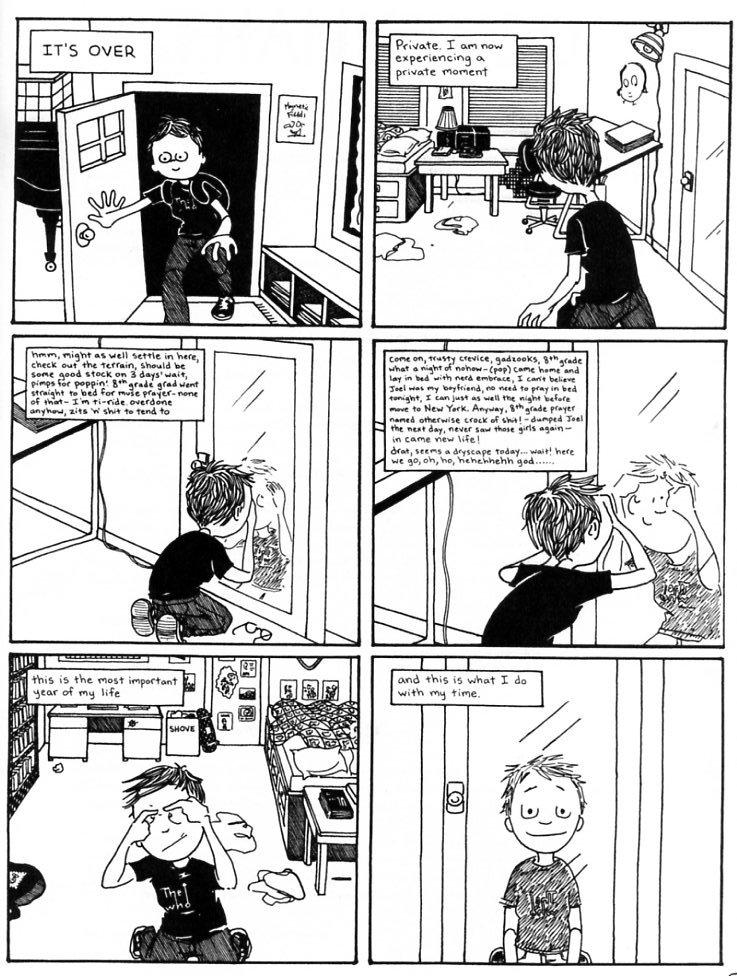

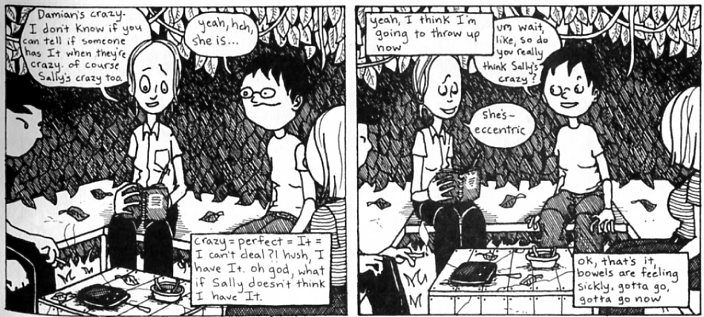

As it happens, in one of the rare interludes when Likewise is not focusing on penises, it turns instead lightly to thoughts of…bowels.

That bit above occurs during what is possibly the most searingly embarrassing sequence in the book; a 30+ page marathon gab session in which Ariel and several friends try with all the earnest might of high school seniors to define It — that elusive virtue which casts a glamor on the doings of some, and the absence of which turns others, despite their best efforts, into lame assholes. Ariel is, in the manner of these things, fairly certain that she has It, even though her asshole is, alas, exceedingly lame, and keeps dragging her off to the bathroom.

So what is It? Ariel defines It as “sort of like an appreciation of certain things in the world…that like not very many people have, but you can tell if someone or something has it.” She also says, “you either have It or you don’t and it has to do with like getting to the root of things? like when you talk about something you talk about what it essentially is.” It, then, is cool; It’s ease with authority; It’s mastery. I think Freud would call it the phallus.

Which makes Ariel’s thoughts about Sally elsewhere in the conversation very a propos:

“crazy=perfect=It=I can’t deal?! hush, I have It. oh god, what if Sally doesn’t think I have It….Yeah, I think I’m going to throw up.”

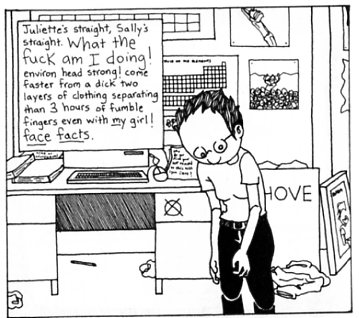

Thinking about Sally makes Ariel worry that she doesn’t have It — which makes sense since, during their relationship, the thing that Ariel always worried was lacking, the thing she feared that maybe-not-so-gay Sally wanted, was the very thing, a penis.

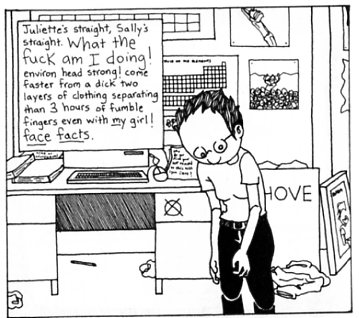

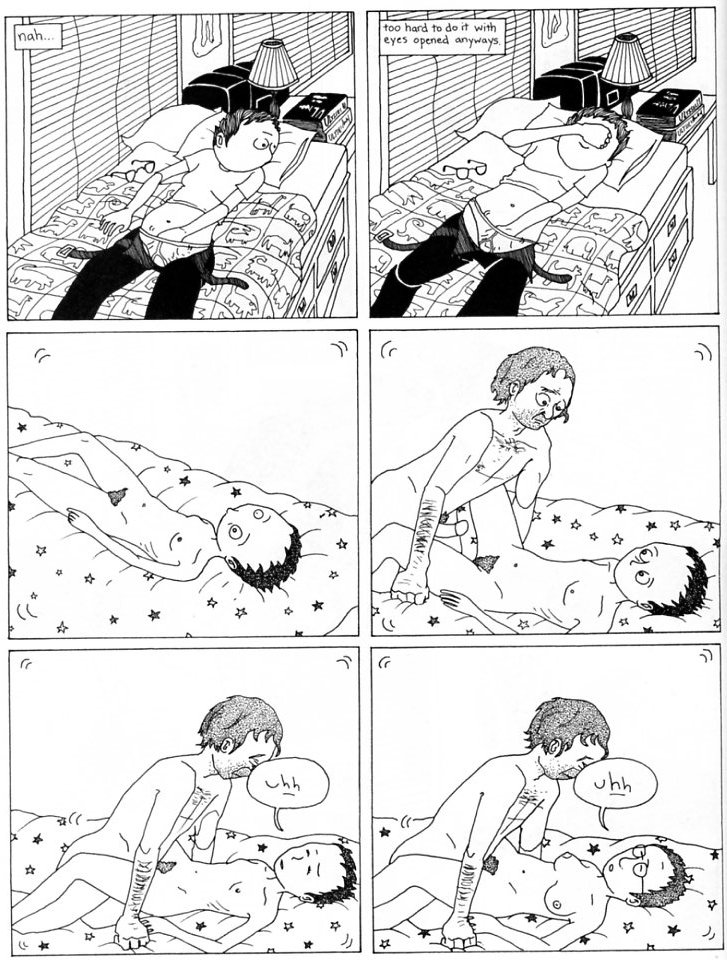

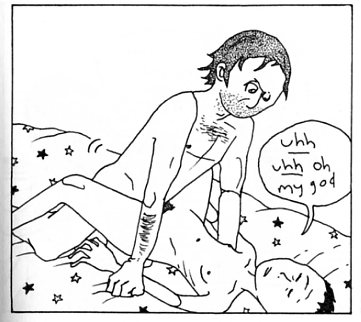

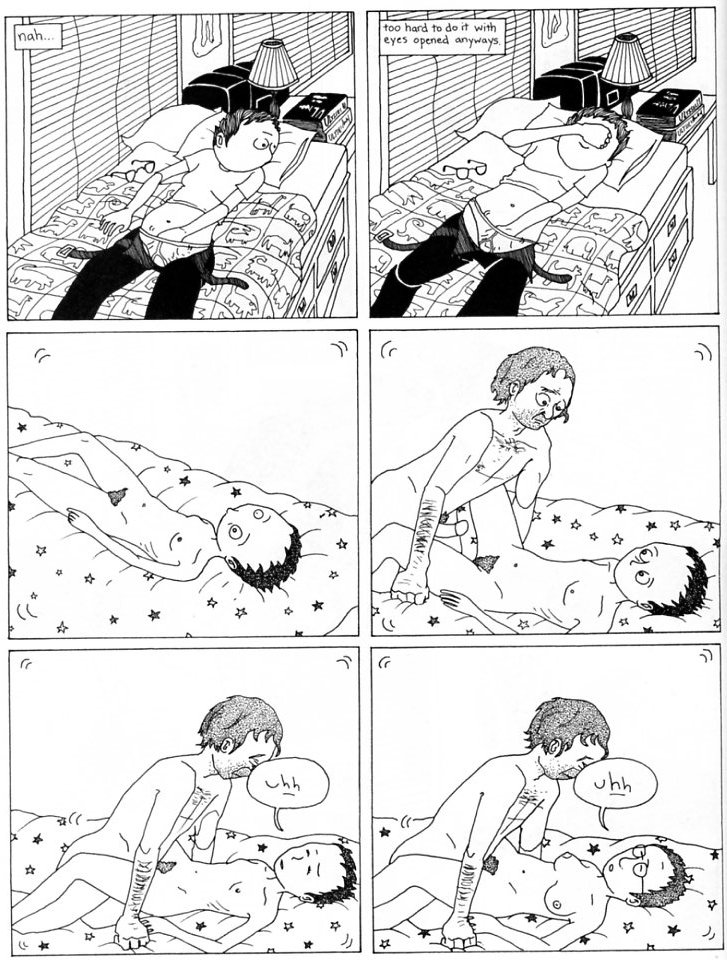

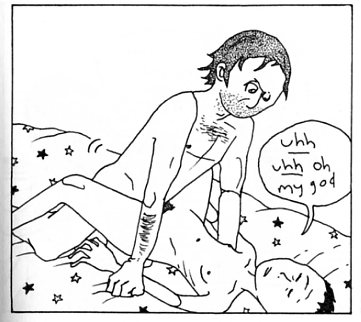

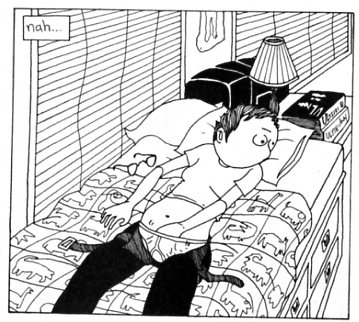

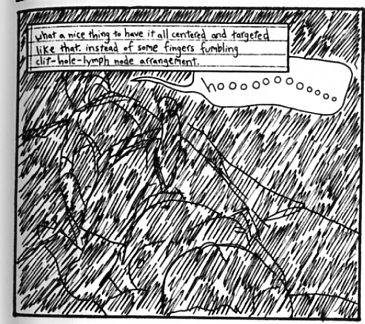

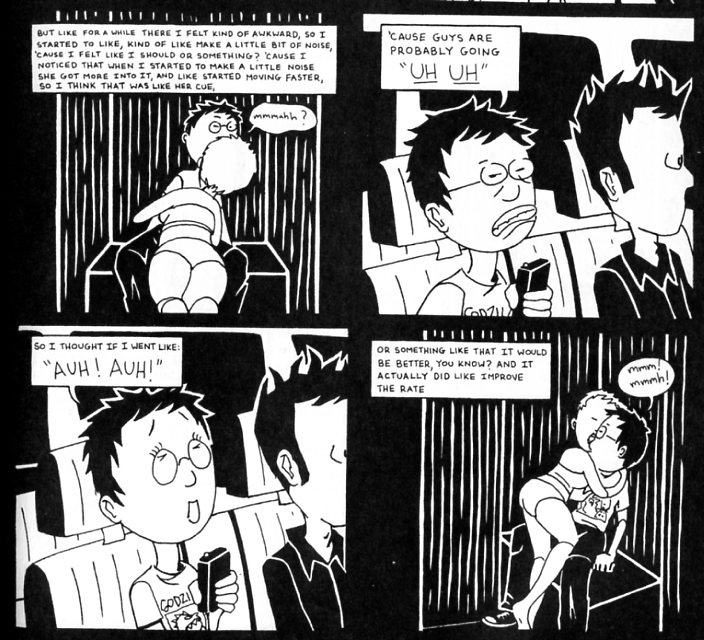

Anxiety about Sally, then, leads to thoughts of penises, and to efforts to grasp and wield them. As in this scene:

Ariel’s fantasy here starts with Sally naked…and then spins off in somewhat unexpected directions. The person fucking Sally is not Ariel, but a man — and the way Ariel seems to be sliding off her slanting bed in the top right panel and onto the similarly slanting guy in the panel below suggests that she may be fantasizing herself as the man. Then, in the last panel, the person being fucked isn’t Sally but someone who, with the glasses and the larger chest, seems like it might be Ariel herself, or perhaps Ariel combined with Sally. Schrag uses the repetitive panel compositions (the starred bed cover across the bottom of the panel, the white space) to emphasize the substitution of identities and desires; the phallus-as-fetish seems to move about the empty half-dream world, looking for the perfect place to attach and center. Wanting Sally leads to chasing the phallus around and around, or in and out, until mastery is finally both achieved and not-so-much:

for the climax we shift back to Sally on the bed…but the guy who is, presumably, climaxing has lost his mouth, which makes him look more than a little ridiculous. He looks, in fact, surprised — and quite a bit like Ariel in the top left of the last facing page, who has also misplaced an orifice, and is also looking at Sally (Ariel is looking at her and Sally’s prom picture):

The man and Ariel both look at Sally the same way; with both desire and alienation. You try to grasp the phallus but the phallus escapes, leaving you nonplussed, gaping, and forced to try to grasp the phallus again. Or just wondering where it is:

I kind of want to get that put on a T-shirt.

As a man, it’s easy to relate to Ariel’s worries about measuring up — worries about measuring up being pretty much what masculinity is about. Ariel’s struggles are especially fraught, though, because it’s not clear what victory would look like. Guys know they want to be Superman, more or less. But Ariel? Succeeding in being a man is, from her perspective, even worse than failing.

That last panel, where she thinks “I’m not a woman” — that’s not a victory. Being taken for a man doesn’t make her a man; it unsexes her. When her phallus is most manifest is when she measures up least.

So the book is a self-hating tale of how a young lesbian wants to be a man, but can’t quite measure up? Well, no. Ariel, like lots of queer high school students, does have got a certain amount of internalized homophobia to work through, as she’d be the first to acknowledge. But that’s not the only thing that’s going on. On the contrary, far from being constitutionally inadequate, Likewise is, in the way of ambitious art, swaggering. If the book’s about wondering where your dick is, it’s also about pointing down and saying, “check this motherfucker!” The long discussion of “It”, for example, contains some of Schrag’s most detailed, obsessive drawing, with carefully delineated leaf placed next to carefully delineated leaf, until the virtuoso craft of the background almost overwhelms the vacuous teen discussion of virtuoso It in the foreground. When Ariel in the comic decares “my comic has It,” it’s both wishful thinking and, in the care and beauty of the drawing, actually true. The very way in which Ariel’s bowel problems undercut her hold on the phallus are in fact a laugh-out-loud delight in playing with It. She demonstrates she has the thing by the skill and humor with which she shows she doesn’t.

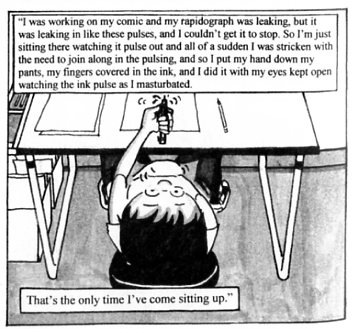

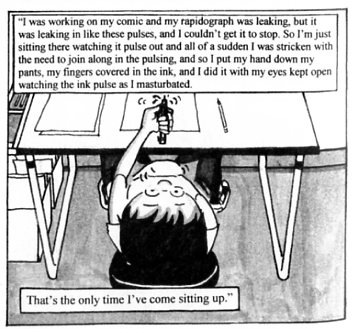

Creativity, in short, is the biggest, most potent penis of all — which is why Ariel comes while holding her pen.

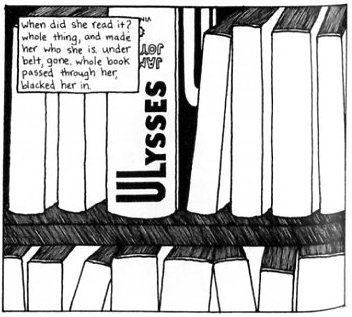

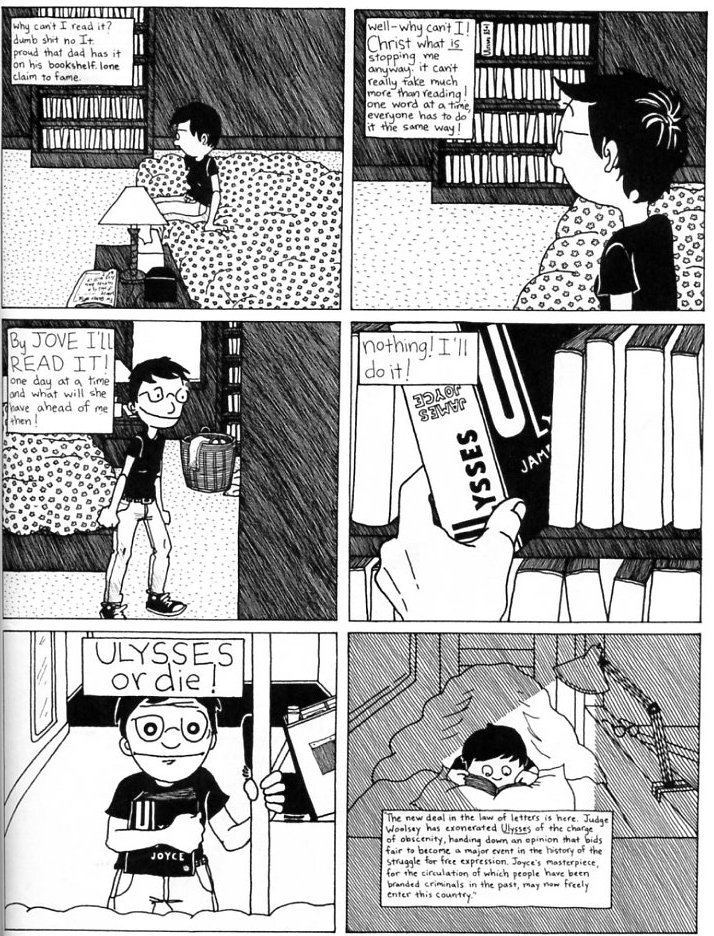

It’s also why Ulysses is so important to this book. My sense is that many readers (like Kristian Williams) see the Joyce influence in Likewise as a more or less insufferable late adolescent affectation. I think this rather misses the point, which is that Joyce in Likewise is thematically presented, not as random anonymous affectation, but as deliberate, specific, lifeline. Ariel is drawn to Ulysses because Sally suggested it. In part, she picks the book up to be like Sally — but in part she picks it up to be to Sally what Joyce has been:

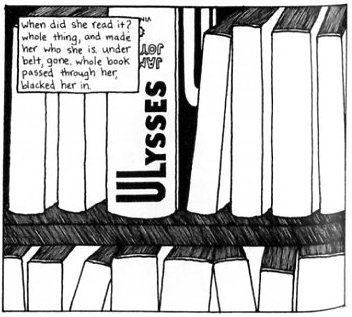

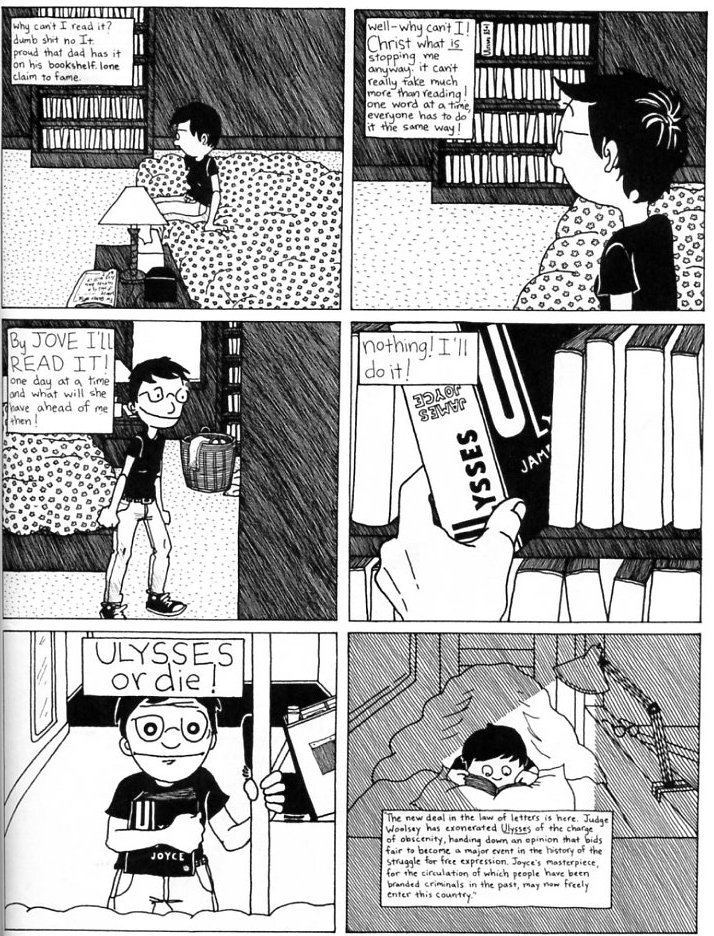

There’s Ulysses standing straight up, a huge tower on the bookshelf, while Ariel thinks “when did she [Sally] read it? whole thing, and made her who she is. under belt, gone. whole book passed through her, blacked her in”. The vision of Ulysses as phallus entering Sally couldn’t be much more clear…and we then move from that, to the next page, where Ariel starts contemplating her own lack of Itness and inadequacy in relation to Sally.

Ariel’s sudden realization that she can have the book is accompanied by grasping It and clutching it to her chest while holding onto that suggestively shaped bedpole. Then she curls under the covers…and starts reading, not Joyce, but the frontmatter account of the obscenity trial. The book is pornography, both because it’s about sex and because it’s instrumental — Ariel is using it to get It up. The page is both triumphant and self-mocking; there’s a recognition I think that metaphor can remake gender, and also a recognition that it can’t. Reading Joyce can turn Ariel into Joyce, and it also really can’t. I find that last panel heartbreakingly funny; big-eyed Ariel clutching the little sliver of light that’s going to keep all that darkness back, so certain she’s found the secret formula that she’s even going to read the boring damn introduction.

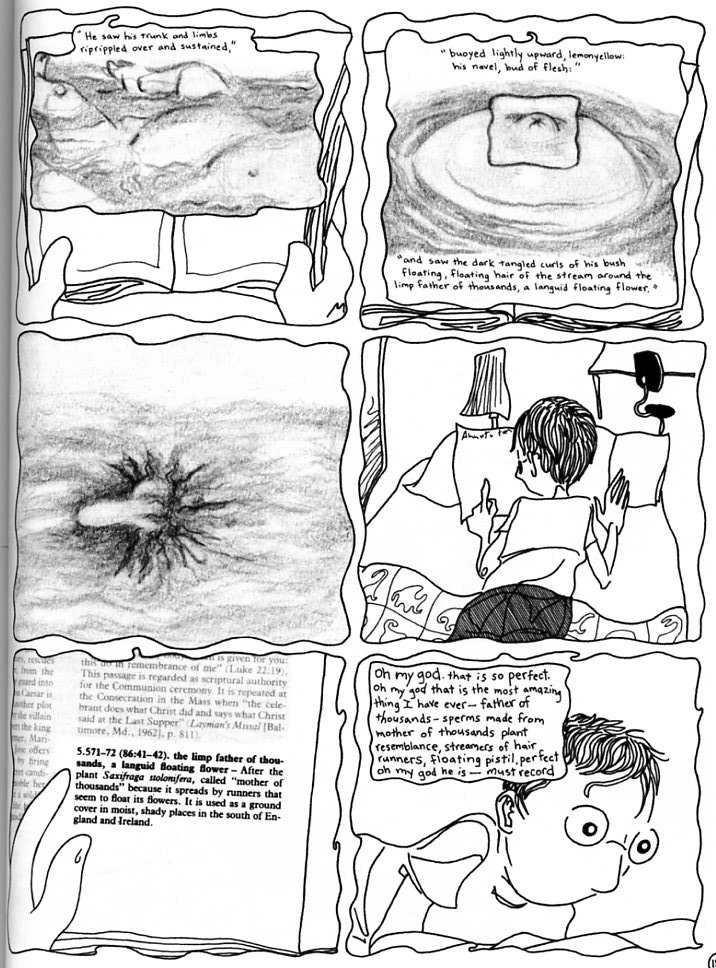

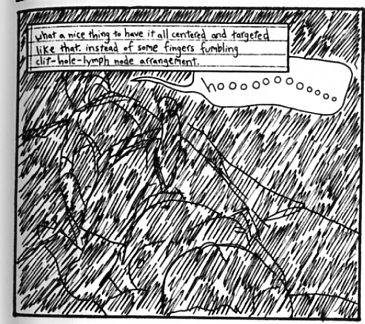

The Joyce-as-penis analogy is made even more explicitly later in the book:

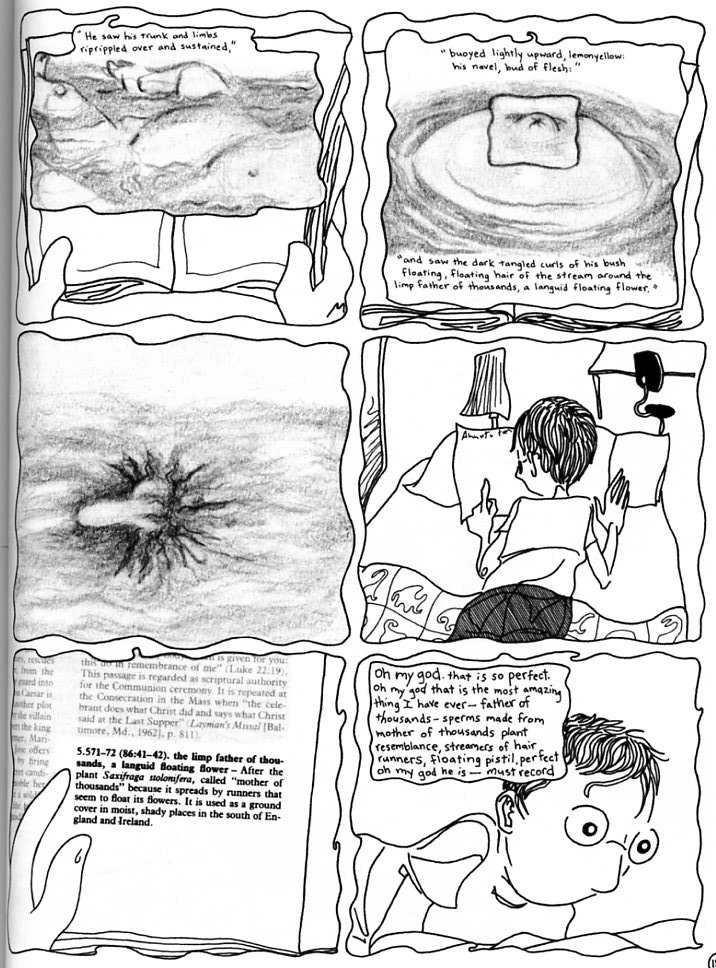

In this sequence, Ariel’s reading Ulysses, and she comes to a section where Joyce describes a penis. He calls it “father of thousands” comparing it to Saxifragia stolonifera, a plant that “spreads by runners that seem to float its flowers” according to the reference book she’s using.

Ariel is wowed: “Oh my god, that is so perfect,” she thinks. This is supposed to refer to Joyce’s genius. But I think it also refers to his penis, especially given the way Schrag draws it — as a sensuously expressive charcoal illustration, perhaps the most beautiful image in the comic.

The best bit here, though, is not the visionary penis, but rather the vision itself. The wobbly panel borders above are not just filligree; they’re there because Ariel’s stoned. Her paean to Joyce’s penis can partially be read as “Joyce — he is a genius, and I appreciate him.” But it can also be read as, “Wow—like— everything’s really meaningful when you’re stoned, dude.” Literary critics singing modernism’s hosannahs are deftly equated with gently tripping potheads.

Joyce’s penis in this passage is, then, lovely, ridiculous — and also feminine. The “father of thousands” is based on the mother of thousands; woman by metaphor, becomes man. Ariel, as creator and character, attempts something similar; taking Joyce’s rhetoric makes her him. She is no longer just a high school journal keeper. She’s an artist, with exactly the kind of It that Sally likes.

Of course, Ariel isn’t actually Joyce. The Inkwell Bookstore blog notes that Schrag’s stream-of-consciousness reads at moments “like a slam poetry parody of Ulysses.” But surely that’s intentional — or, at least, self-aware and thematized. Being Joyce isn’t a realistic option any more than being a man is a realistic option — which is to say, it is and it isn’t. Ariel can buy a dildo and enjoy aspects of her butchness

And she can enjoy Joyce and adopt bits of his language and mojo. But none of that magically give her a phallus.

Or perhaps the real problem is that it does. The phallus is basically a magic totem anyway. If Alan Moore can worship an imaginary snake deity and derive real power from it, then Ariel Schrag can surely get the same effect by worshiping an actual historical Joyce. But precisely because they have power, metaphors have consequences. If you’re going to use Joyce as your phallus, then you’re committed to rotating round that center. Ariel picks up Ulysses in order to possess Sally — and as long as she’s holding Ulysses, she can’t let Sally go.

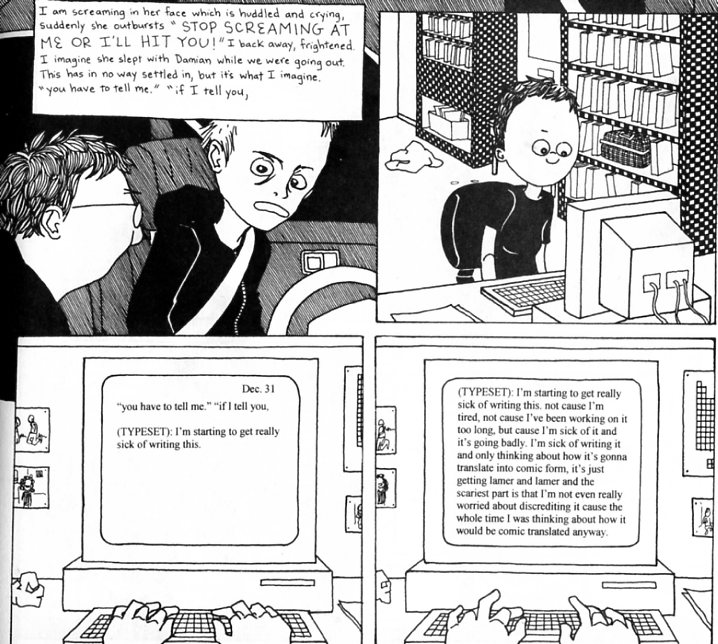

Ulysses is, for Schrag, a metaphor for run-on sexual obsession. Which is why, Ariel’s decision to move on with her live has to be accompanied by a decision to stop talking like (a slam poetry version of) Joyce.

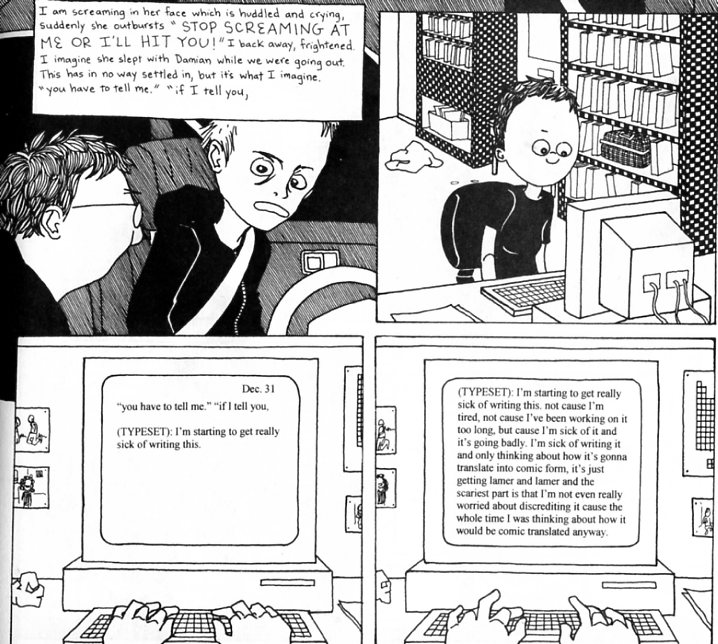

Up to this moment, about two-thirds of the way through the book, Schrag has mostly been using stream of consciousness, and mostly writing about Sally. In this scene, though, she pulls back to a meta-moment; we see her typing on the computer…and what she’s typing is that she’s sick of writing about Sally.

In my interview with Schrag she explained the stylistic shift in the book following this scene as follows:

what happened in the senior year, the ways I was recording everything became more important than what was happening…I was totally removed from my surroundings. So the way in which I recorded the present ended up dominating everything. So halfway through the book, the stream of consciousness narration sort of recedes and the story is only told through these three different methods: what’s typed on a computer, what’s handwritten in a journal, and what’s recorded on a handheld tape recorder. So halfway through the book the methods are…I mean the methods are introduced as recording methods in the beginning, but the narration is just her stream of consciousness, but later in the book the narration changes so it’s the actual typed words or the actual words in the notebook, or the actual tape recording. Things that are typed on the computer, the text box is actual computer type and the drawing is done with an ink wash; things that are hand-written in a journal, the text is scrawled and the drawings are very loose and rough; things that are tape recorded, there’s no narration, and the dialogue appears in square boxes, and it’s done all in black and white. I wanted to shift between those modes of recording and have which mode was being used be more obvious.

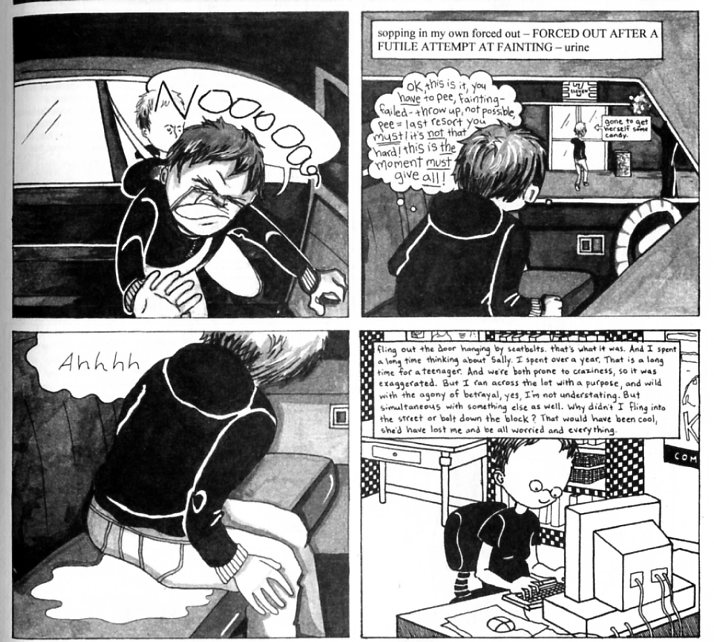

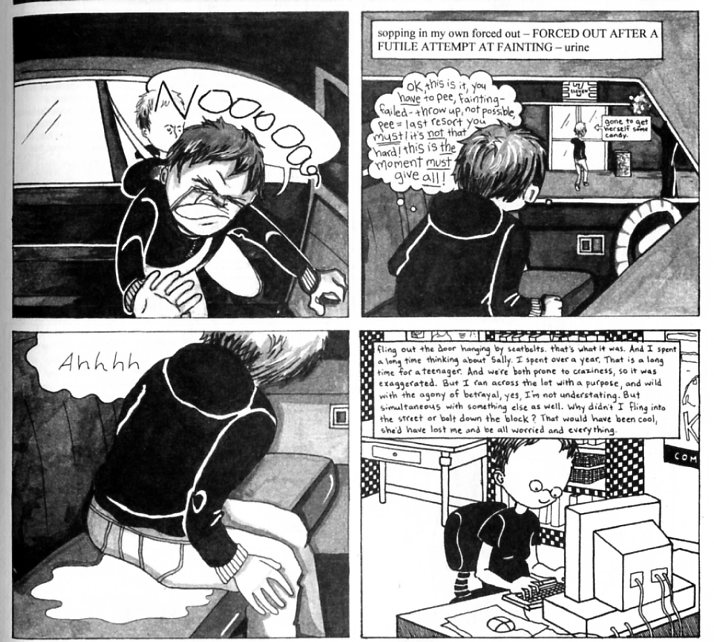

Here Schrag sees the stylistic change in the book as a meta-pocalypse; a swallowing of reality by recording. I think it’s also possible to see it, though, as about rejection of both Sally and the Joycean penis that Ariel has been carrying for her. Almost immediately following the stylistic change, Ariel deliberately pees in Sally’s car:

Peeing your pants pretty much defines infantilizing — it’s not, in any case, very masterful, and certainly not It. And yet, at the same time, Ariel obviously sees it as a kind of triumph — “fainting failed – throw up not possible, pee= last resort you must!” Peeing here is a calculated tantrum; a rejection of one of the earliest-learned social conventions, which is also a rejection of the law, or phallus.

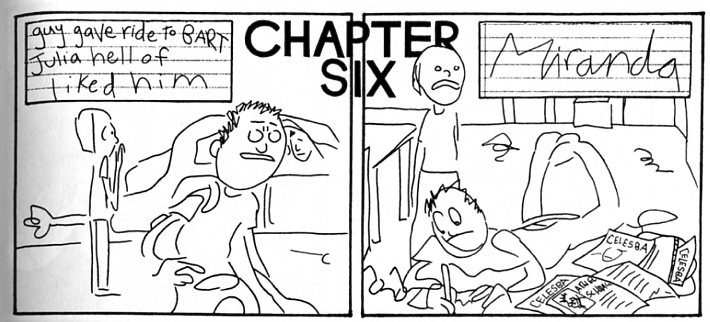

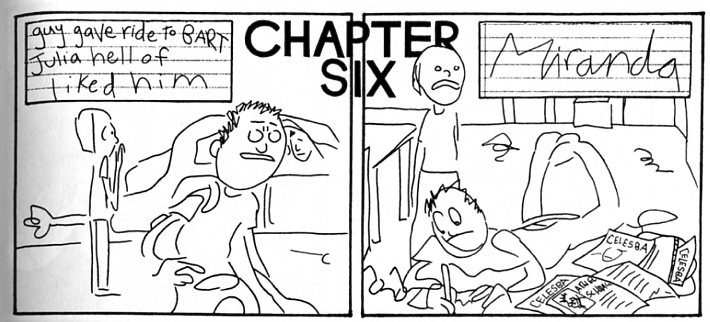

The rest of the book follows from there, as the obsessively controlled Schrag goes about, just as obsessively, releasing control. The focus on the means of recording becomes (in a proud avant-garde tradition) a way of introducing randomness into the creative process, of finessing authorial intent. Long passages of the comic are direct transcriptions of tape recordings, complete with tape hiss and scenes ending whenever someone happens to turn the machine off. Other sections are taken directly from Ariel’s journal notes, with the drawings done as uncompleted sketches.

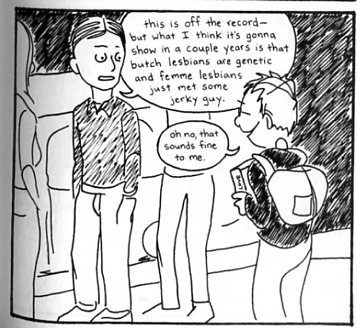

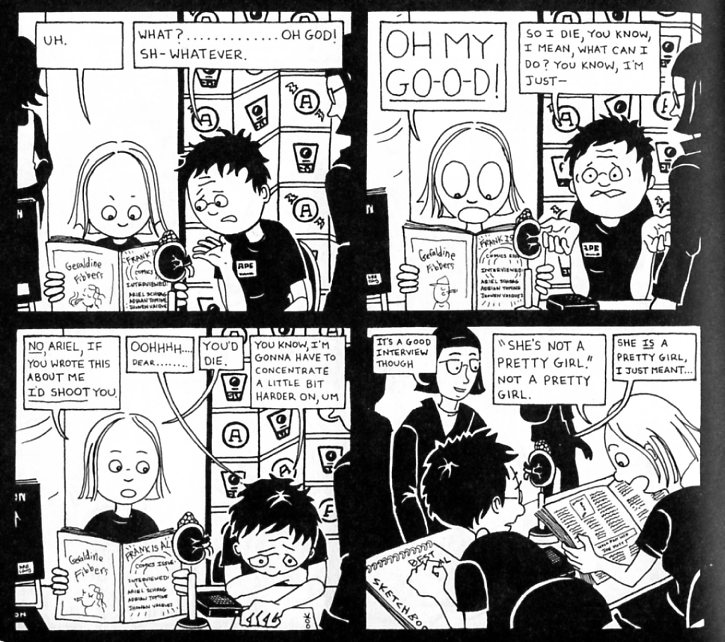

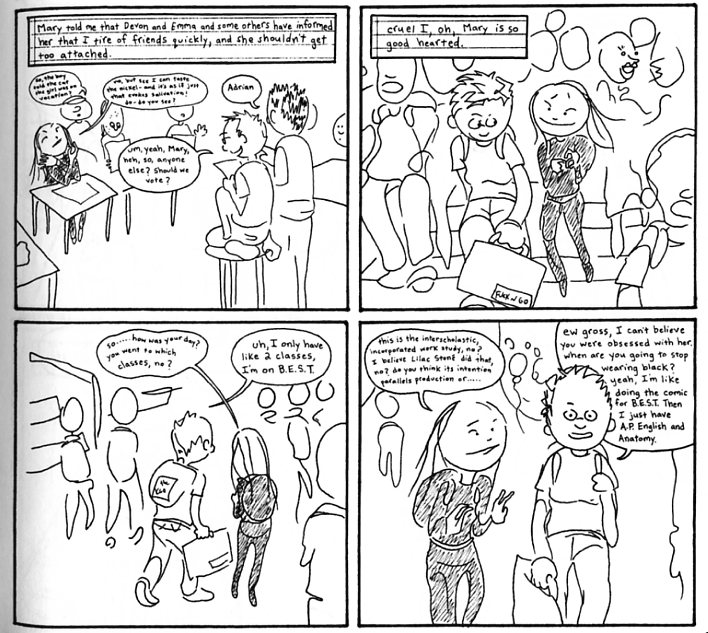

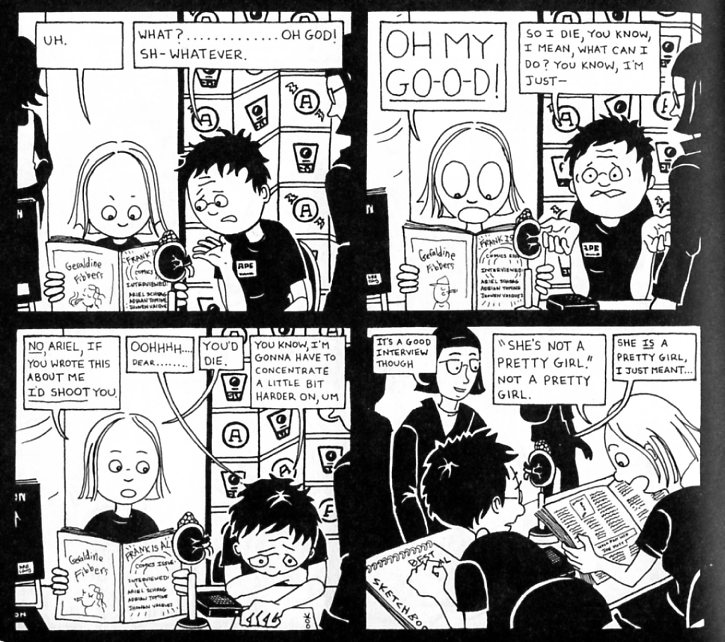

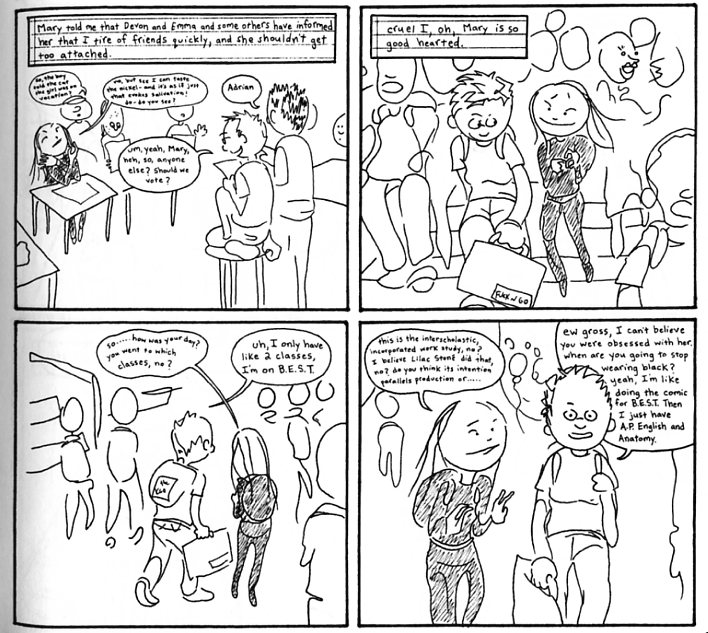

The effect of both of these choices is to create narratives that are closer, in some ways, to Schrag’s earlier comics than to the first part of Likewise. A sequence taken from recordings made by Ariel and her friend Julia at a comic convention is built around laugh-out-loud dialogue, acid observation, and gossip, and has the episodic structure of much of Awkward and Definition.

Analogously, Schrag’s sketchy pencil drawings evoke the cruder style of Awkward, her first comic done when she was a sophomore.

There’s also a long section in which Ariel and her friend Zally go to a strip club to see if Ariel can get off, which is very reminiscent of the long episode in Potential when Ariel and Zally planned and executed Ariel’s loss of virginity (complete with anticlimactic, though ultimately satisfying, ending). And, perhaps most obviously, as the book moves towards its conclusion, Ariel starts messing around with a guy, pointing back to her freshman and sophomore years, when she identified as straight or bi.

As this suggests, though Joyce and It are in some sense shelved, penises still pop up throughout the last portion of the book.

Ariel isn’t really, after all, going back to her older work (which, in any case, featured a certain number of penises itself.) She’s not so much laying down her desire to measure up as she is looking around for different modes, shifting away from Joyce’s style in order to experiment with different modes and ideas — in a way which is also (as she mentioned in our interview) inspired by Ulysses. She’s not returning to an unconscious childhood, but rather reworking her past into something she can use now. Her sketches look like Awkward, and may be inspired by Awkward, but they’re definitely not Awkward, either in their origin or their execution. The drawings in Awkward were cute but restrained — they looked like cartoons. The sketches here, on the other hand, look like artist’s sketches; the lines are quick, with a messy, expressive brio, and the shading (when there is any) has a delightful, scribbly energy. Purely as art, they may be my favorite of her drawings,and they can convey remarkable subtlety. In the sequence below, for example, there’s a sensuality in the way Mary’s shaded form bends back and forth towards Ariel as they walk, while all the figures around them dissolve into background blobs.

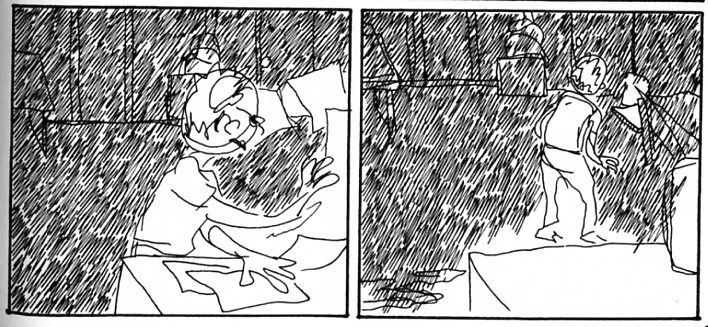

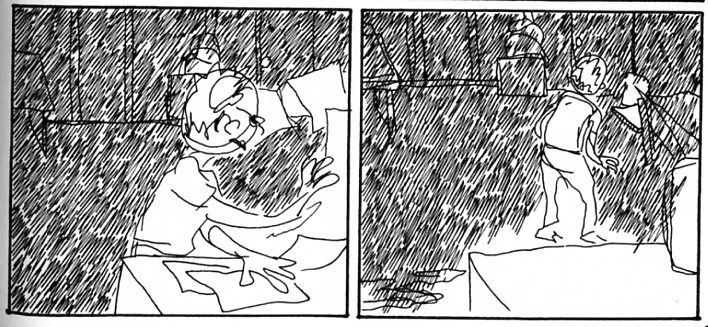

I also love the panicked violence in the panels below, as Ariel’s distorted arms sweep across her desk looking for her protractor, and then the clumsy heaviness of her body in the second panel, contrasting with the vibrating scribbles of the dark.

If this is Awkward, it’s Awkward that’s gotten older and wiser and cockier; Awkward with a swagger.

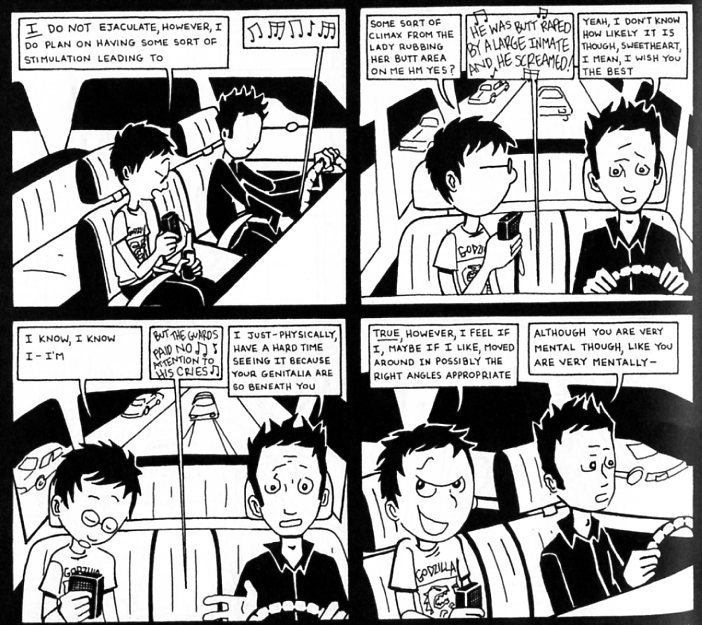

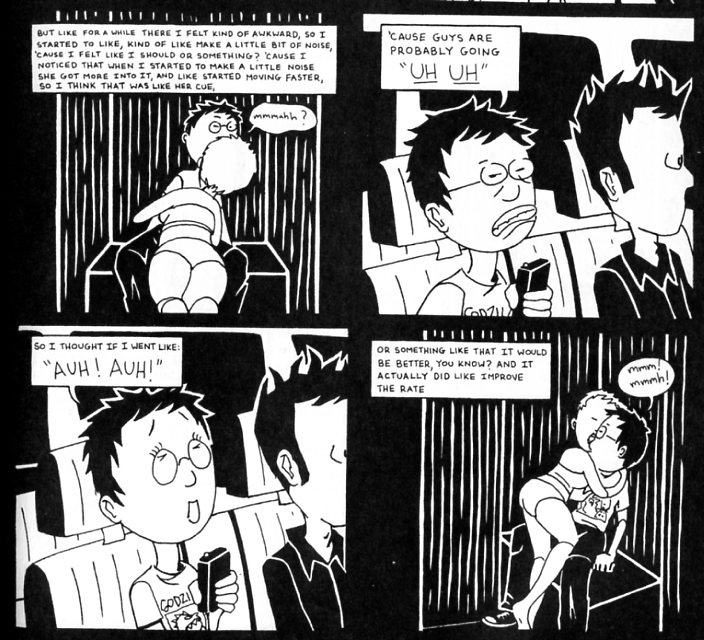

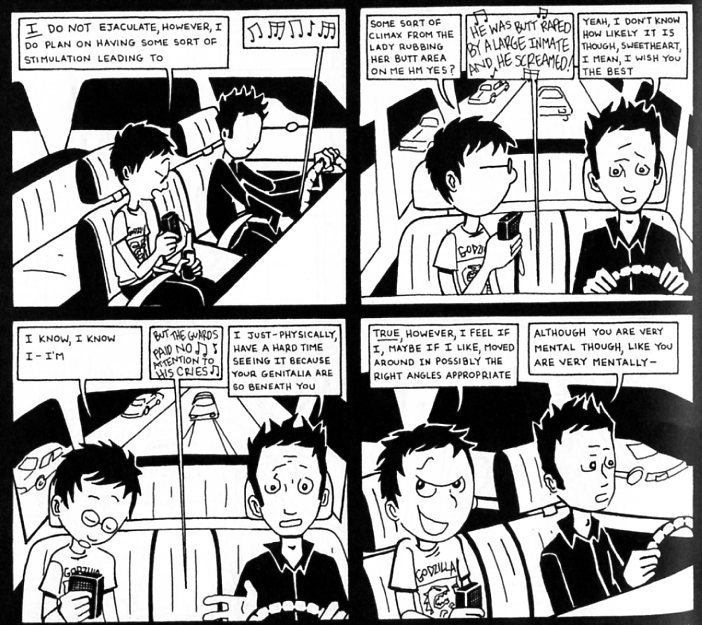

Perhaps the best account of where Ariel’s phallus seems to have gone and why is in the strip club scene with Zally. Here’s the back and forth about that section from the interview I did with her:

That’s interesting. Because there’s also the scene where you go to the strip club with Zally, and you seem to be really trying to approach it in a guy way — a kind of swaggering, I’m going to get off on this approach.

The thing I thought about was funny in the whole scene…Zally went to the strip club and the girl rubbed on him and came, and I’m thinking, so that’s what I’m going to do…a five-minute ordeal. And then my experience is this long ordeal and I’m intellectualizing and over-thinking and it’s like the opposite. What I wanted was the macho posturing, but instead there’s this twenty minute ramble about every minute detail.

It seems to me that that’s kind of reflected in your comics as well though. That is, part of the reason that you have trouble getting off is that you are thinking about what the woman is thinking, or you’re interested in that. In your comics in general, even though they’re autobiography, you’re really interested in other people.

I don’t really understand comics that don’t have more about other people. I mean if I’m writing in my diary I’m going to write down the quotes that other people said, I’m not going to write down what I said to other people.

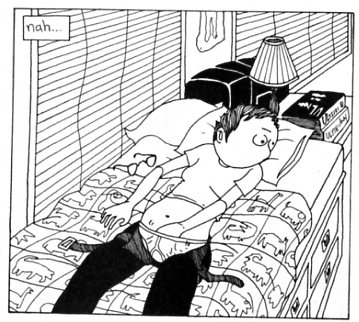

What happens at the strip club is that Ariel doesn’t get off…essentially because she doesn’t have a penis.

And yet, if she doesn’t have a penis, she does have a phallus:

The tape-recorder itself functions through the last part of the book as a violent stick; Ariel’s always shoving it into people’s faces and trying to get them to talk about sex. She uses it to control the other people’s responses, and to control the narrative (by trying to record what’s going on, sometimes even surreptitiously.)

But if it’s a phallus, it’s a phallus that’s about conversation and connection, rather than about the more self-contained drives in Ariel’s Joycean stream-of-consciousness. The fun here is about back and forth; about figuring out what the girl is thinking and then analyzing the experience by talking it over with a friend rather than by internalized obsession.

In the interview, I characterized Schrag’s take on the strip club as gendered female, in comparison to some male autobio writers. I think that’s defensible — but I also think that one thing that happens in Ariel’s experience in the strip club is that the exact gender implications become hard to pin down. Is talking sex over with your friends really gendered feminine? That’s an awfully guy thing to do. Similarly, jerking off with a friend in a club seems definition male homosocial.

In this narrative mode, though, the sliding back and forth and around the phallus, or lack thereof, doesn’t seem nearly as fraught; if the lap dance was kind of uncomfortable, it was also funny, and if she didn’t cum from that, she can always cum later with a buddy. Similarly, her sexual encounters with various friends, and even her interactions with Sally (with whom she finally, finally breaks up), become less emotionally overwhelming. Is that the distancing of meta; the constant drive to observe and record herself pushing authentic reality away? Or is it working through different ways of holding onto reality — and maybe finding that grasping it a little less firmly makes it easier to hold?

“man cannot be happy: happiness is the longing for repetition…modern man’s plight is choice” That’s a gendered statement; we’re talking about man, and, indeed, about the way Ariel relates to Joyce and to It in the beginning of the book. She wants to repeat her experience with Sally; she wants the mastery of choosing and control.

In the second part of the book, though, she escapes both these things, at least provisionally. She finds a way to create which to some extent undercuts choice, and in so doing ceases to try quite so hard for repetition.

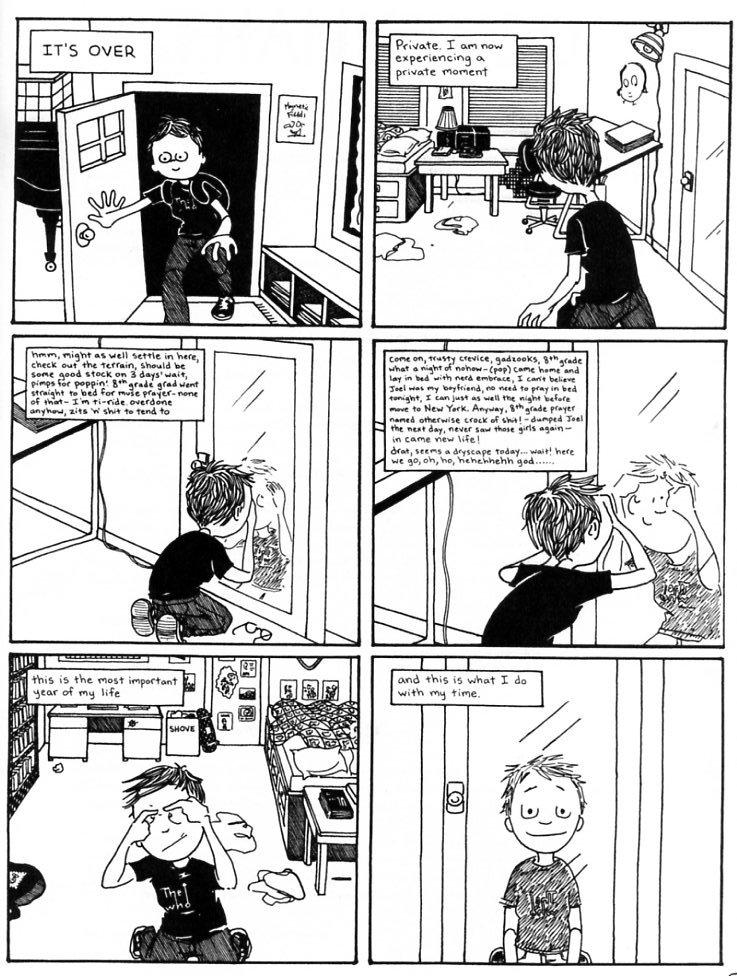

The last page of the book returns to the Joycean stream-of-consciousness, but not to any penises that I can find. Instead, the sequence is about Ariel popping her zits, and she seems contented enough. The stream-of-consciousness seems not like a self-circling outlet for obsession, nor a way to wow and possess, but just another style she can use. “This is the most important year of my life, and this is what I do with my time,” she concludes, staring into the mirror with the last pimple popped.

The “this” she’s doing with her time is in part finishing her book— a massive, ambitious work of art which she can pull out and brandish to awe and stun the neighbors. But “this” is also the everyday task of popping pimples. To finally have capital-It is to know you don’t need It after all. Which leaves your hands free for all sorts of things, both trivial and otherwise.

___________________

This is the second post in the Likewise Roundtable. The first post surveying reviews of Likewise is here.

You can read the entire LIkewise Roundtable here.