“Now take that frequency and see if you can amplify it,” Jiaying says.

Skye wants to obey her new mentor but is frightened of her own powers. “The last time I did something like this a lot of people got hurt.”

“You can’t hurt the mountain. And you’re not going to hurt me. Don’t be afraid.”

Skye braces herself, turns toward the snow-banked mountain range, and raises her hand in standard superhero style. Soon an orchestra of emotion-signifying strings rises from the soundtrack, and then a CGI avalanche tumbles scenically down the mountain side.

Skye gives a shocked smile. “I moved a mountain.”

“Remember that feeling. It’s not something to be afraid of.”

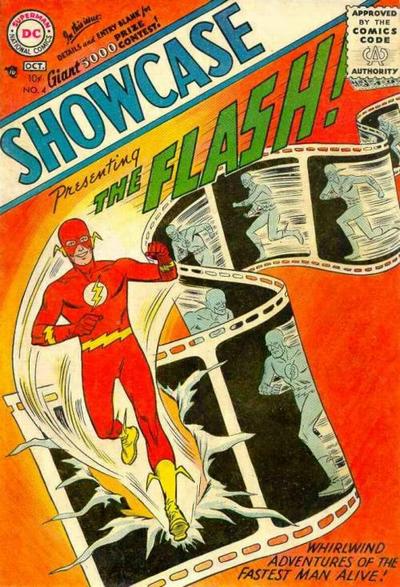

This is episode 2.17 of Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., which aired April 14, eleven days before the Nepal earthquake. In Marvel Comics, Skye goes by the codename “Quake.” In the TV show, she’s just acquired her superpowers and has been whisked away to a secret mountain sanctuary to be trained by its semi-immortal leader. Jiaying never names the Himalayas, but that’s the main location of the Inhumans’ secret city in the comics, and in the show Skye was found as an infant in China. During the same episode, she discovers that Jiaying is her mother—played by Dichen Lachman, an actress of German, Australian, and Tibetan background. Lachman was born in Kathmandu, miles from the earthquake’ epicenter, which triggered an avalanche on Mount Everest, killing 19 people. The total death toll is over 7,000.

The coincidences are hard to comprehend. My wife and I watch S.H.I.E.L.D. with our son, and I remember her protesting from the other end of the couch that Skye’s avalanche could have hurt plenty of people. We’re usually a day or two behind streaming episodes, so this was still at least a week before the actual earthquake. We teach at Washington & Lee University, where a spring term roster of students was flying to Nepal for an interdisciplinary Economics and Religion course. I bumped into a wife of one of the professors in Kroger, and she said news of the quake broke just hours before their flight was to take off. She had been going too.

That’s as close as I get to the disaster.

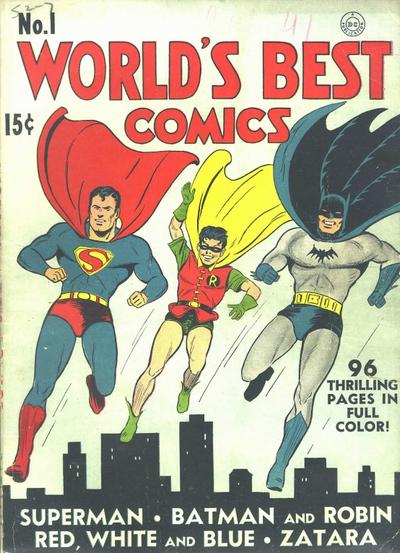

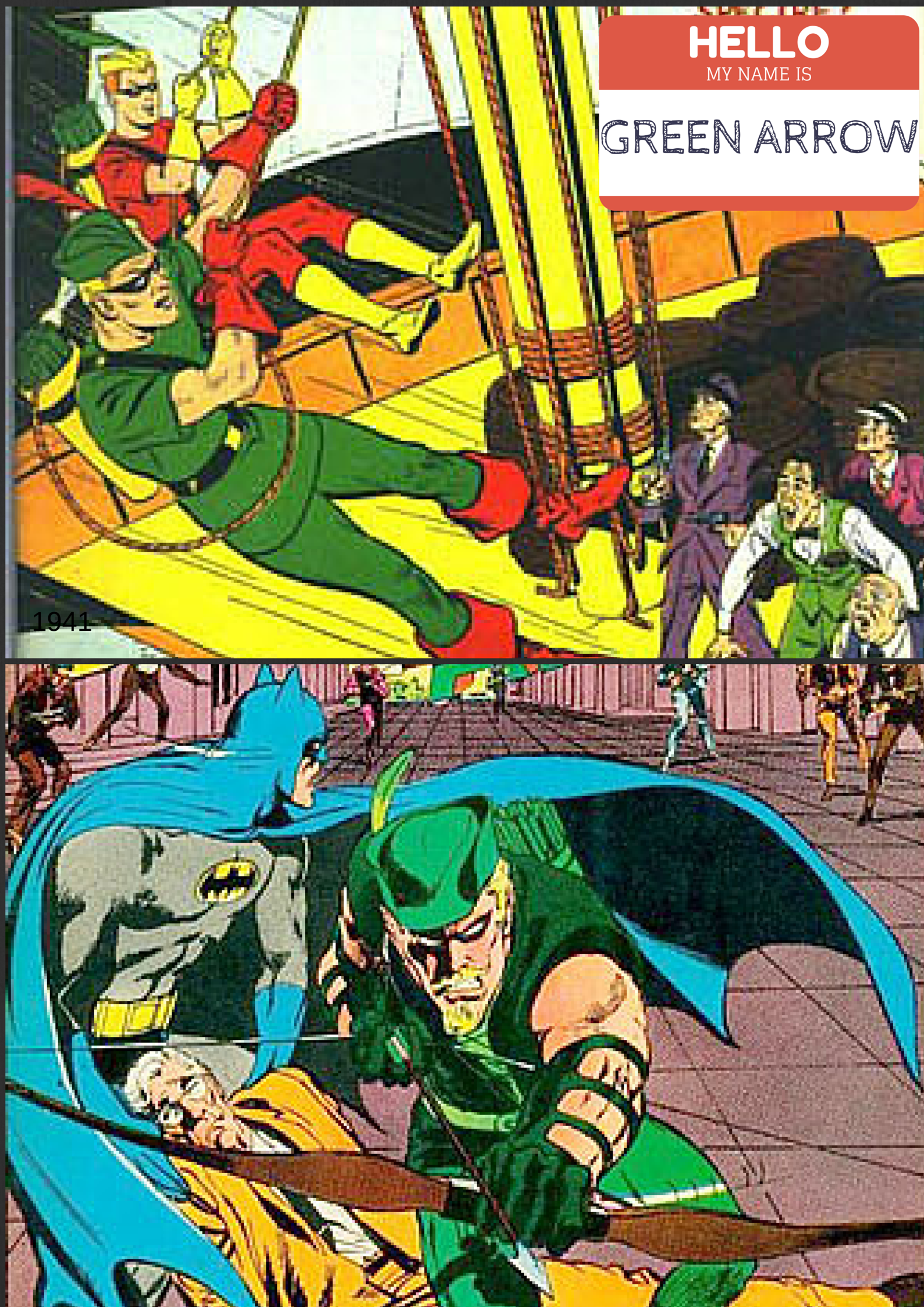

This time last year, I was teaching my “Superheroes” course, and gave a guest lecture on colonialism and Orientalism in the superhero genre for Professor Melissa Kerin’s “Imaging Tibet” course. I showed image after racist image of European Americans visiting the magical realm, acquiring superhuman powers, and then returning home to battle evil. Batman Begins opens with Bruce Wayne scaling a Himalayan mountain side to arrive at Nanda Parbat, home of the League of Assassins, where Bruce would train with the semi-immortal Ra’s al Ghul to become Batman.

It wasn’t airing yet, but the current season of the Arrow TV show is centered around Nanda Parbat too. The TV Ra’s is played by a former Australian rugby player, and the equally European-looking actress playing his daughter speaks with what I think is supposed to be a British accent. Only the Ninja-like underlings look Asian. Nanda Parbat is a variation on Nanga Parbat, the western-most mountain of the Himalayas in Pakistan.

My wife, son and I sat on the same couch, watching Oliver Queen (“Green Arrow” in DC Comics) agree to become Ra’s al Ghul’s heir in exchange for Ra’s saving Oliver’s mortally wounded sister by dunking her in his magic fountain of semi-immortality.

The ceremony involves a virginal white dress and antiquated pulley system of wood and rope. After vanishing under the bubbles, she catapults twelve feet through the air to land cat-like on the fountain ledge.

“Tibet is one wacky place,” I said, and my wife laughed.

That’s episode 3.20, which aired on Wednesday April 22nd, three days before the Saturday earthquake. In the week after, Oliver would be brainwashed into a heartless mass-murderer plotting the destruction of his own city, and Skye would use her newly controllable powers to rescue a fellow Inhuman and a cyborg S.H.E.I.L.D. agent from Hydra’s Antarctic prison laboratory.

On April 29, NPR reported on the flood of people trying to leave Kathmandu, and The Guardian described the rise of tensions over the slow pace of aid. The same day actor Ryan Phillippe told Howard Stern that he had an upcoming meeting with Marvel, hinting that he may be cast as Iron Fist in the new Netflix superhero show about another European American traveling to the Himalayas and gaining superpowers.

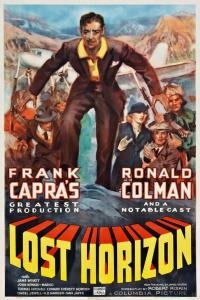

The collective origin point for all the superhero exoticism is Shangri-La, the magical Himalayan city of the 1937 film and 1933 novel Lost Horizon. It features a semi-immortal High Lama who recruits a European American to be his heir and rule the secret mountain paradise.

Edward Said asks: “How does Orientalism transmit or reproduce itself from one epoch to another?”I answered last year in a PS: Political Science & Politics essay: “In the case of superheroes, it is through the unexamined repetition of fossilized conventions that encode the colonialist attitudes that helped to create the original character type and continue to define it in relation to imperial practices.” I continued the thought in the book manuscript of On the Origin of Superheroes I sent to my press for copyediting last month: “The 1930s is an Orientalist pit superheroes may never climb out of.”

My claims are already outdated. These TV shows aren’t just continuing superhero Orientalism—they’re digging the pit deeper. And they’ve been digging it while actual Nepalese rescue workers have been digging earthquake victims from actual pits.