To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman.

The above must be one of the niftiest opening sentences in pop literature. It begins the first Holmes short story, ‘A Scandal in Bohemia,’ which appeared in the June 1891 edition of The Strand, promising readers a fitting sequel to the two Holmes novels. “A Scandal in Bohemia” continues, in the voice of Holmes’ friend Dr Watson:

I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler.

Aha! So the temptress is named.

All emotions, and that one in particular, were abhorrent to his cold, precise but admirably balanced mind. He was, I take it, the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen, but as a lover he would have placed himself in a false position. He never spoke of the softer passions, save with a gibe and a sneer. They were admirable things for the observer — excellent for drawing the veil from men’s motives and actions. But for the trained reasoner to admit such intrusions into his own delicate and finely adjusted temperament was to introduce a distracting factor which might throw a doubt upon all his mental results. Grit in a sensitive instrument, or a crack in one of his own high-power lenses, would not be more disturbing than a strong emotion such as his.

The reader is invited to share such lofty anti-emotional rationalism, but the invitation, we sense, is ironic.

And yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.

At this point we could write the rest of the story with ease, couldn’t we? A tale of how this flinty, sentiment-hating, frozen character was brought to emotional life, awakened by the warmth of a passionate woman…

Well, no.

But before we continue, let’s look at the place of women in the adventures of Holmes, and in the life and mind of the great detective’s creator, Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930).

A.C.Doyle

Feminists might well snort with exasperation at the depiction of the average woman in the Holmes canon of stories. Most are victims, frail vessels in need of succor and rescue; even the rare crooks among them tend to be under the domination of a strong-willed male villain (cf. ‘The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet’).

And yet, and yet…

Doyle’s attitude to women was typical of a middle-class British man born and raised in Victorian times: one of patriarchal and patronising chivalry. Women were to be protected and provided for, but men were the leaders, almost surrogate parents.

This view, however, was tempered by Doyle’s admiration for strong women. The source of this can be inferred from the case of his own parents. While his father, Charles, was an alcoholic depressive and possible schizophrenic who effectively dropped out of the household and remained a burden on his family, Doyle’s mother, Mary, was the proverbial tower of strength. She provided for the family and despite poverty managed to send Doyle to study medecine at Edinburgh University.

So Doyle was conflicted about women. He opposed suffrage for them, but made exceptions for tax-paying property owners and unmarried professionals. He championed the cause of woman doctors and solicitors. He militated for a reform of the Divorce Laws, which were at the time cruelly stacked against women. A lapsed Catholic himself, he was angrily opposed to young Catholic women being buried in convents.

And if we look at the stories again, we find they show more than a few figures of strong women: the determined American runaway bride, Hatty Doran, in ‘The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor’; the chillingly lethal villainess Maria Gibson in ‘The Problem of Thor Bridge’; or even the quiet Mary Sutherland in ‘A Case of Identity’ who, though she has a comfortable private income, insists on working for a living as a typist.

And then there is Irene Adler.

Back to the story (beware spoilers):

A visitor arrives at Holmes’ rooms, introducing himself as Count Von Kramm, an agent for a wealthy client. Holmes quickly deduces his true identity:

“If your Majesty would condescend to state your case,”

he remarked, “I should be better able to advise you.”

The man sprang from his chair and paced up and down the room in uncontrollable agitation. Then, with a gesture of desperation, he tore the mask from his face and hurled it upon the ground. “You are right,” he cried; “I am the King. Why should I attempt to conceal it?”

“Why, indeed?” murmured Holmes. “Your Majesty had not spoken before I was aware that I was addressing Wilhelm Gottsreich Sigismond von Ormstein, Grand Duke of Cassel-Felstein, and hereditary King of Bohemia.”

The King is engaged to a young Scandinavian princess. However, five years before he’d had a liaison with an American opera singer, Irene Adler, who has since then retired to London. Fearful that should the family of his fiancée learn of this the marriage would be called off, he had sought to regain letters and a photograph of Adler and himself together. The King’s agents have tried to recover the photograph through sometimes forceful means, burglary, stealing her luggage, and waylaying her. An offer to pay for the photograph and letters was also refused. With Adler threatening to send them to his future in-laws, which Von Ormstein presumes is to prevent him marrying, he makes the incognito visit to Holmes to request his help in locating and obtaining the photograph.

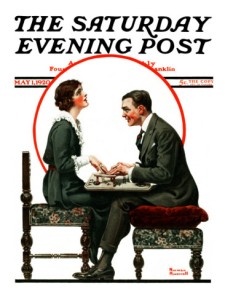

The next morning, Holmes goes out to Adler’s house, disguised as an out-of-work groom. He learns that Adler has a gentleman friend, the lawyer Godfrey Norton, who calls at least once a day. On this particular day, Norton comes to visit Adler, and soon afterwards the two go to a church. Holmes follows, and finds himself dragged into the church to be a witness to Norton and Adler’s wedding.

Holmes changes into another disguise as an old clergyman; he and Watson go once more to Adler’s house.

When Adler’s coach pulls up, a fight breaks out between men (hired by Holmes) on the street over who gets to help her down. Holmes rushes into the fight to “protect” her, and is seemingly struck and injured. Adler takes him into her sitting room, where Holmes motions for her to have the window opened. Watson tosses in a smoke bomb and shouts “FIRE!”

Adler rushes to get her most precious possession at the cry of “fire”—the photograph of herself and the King. It was kept in a recess behind a sliding panel. He explains all this to Watson in the street before being bid good-night by a familiar-sounding youth.

Illustration by Sidney Paget

We had reached Baker-street, and had stopped at the door. He was searching his pockets for the key, when someone passing said:—

“Good-night, Mister Sherlock Holmes.”

There were several people on the pavement at the time, but the greeting appeared to come from a slim youth in an ulster who had hurried by.

“I’ve heard that voice before,” said Holmes, staring down the dimly lit street. “Now, I wonder who the deuce that could have been.”<

When Holmes, Watson, and the King arrive the next morning at Adler’s house, her elderly maidservant informs them that she has hastily departed for the Charing Cross railway station. Holmes quickly goes to the photograph’s hiding spot, finding a photo of Irene Adler in an evening dress and a letter dated midnight and addressed to him:

“My Dear Mr. Sherlock Holmes,

—You really did it very well. You took me in completely. Until after the alarm of fire, I had not a suspicion. But then, when I found how I had betrayed myself, I began to think. I had been warned against you months ago. I had been told that, if the King employed an agent, it would certainly be you. And your address had been given me. Yet, with all this, you made me reveal what you wanted to know. Even after I became suspicious, I found it hard to think evil of such a dear, kind old clergyman. But, you know, I have been trained as an actress myself. Male costume is nothing new to me. I often take advantage of the freedom which it gives. I sent John, the coachman, to watch you, ran up stairs, got into my walking clothes, as I call them, and came down just as you departed.

“Well, I followed you to your door, and so made sure that I was really an object of interest to the celebrated Mr. Sherlock Holmes. Then I, rather imprudently, wished you good night, and started for the Temple to see my husband.

“We both thought the best resource was flight, when pursued by so formidable an antagonist; so you will find the nest empty when you call to-morrow. As to the photograph, your client may rest in peace. I love and am loved by a better man than he. The King may do what he will without hindrance from one whom he has cruelly wronged. I keep it only to safeguard myself, and to preserve a weapon which will always secure me from any steps which he might take in the future. I leave a photograph which he might care to possess; and I remain, dear Mr. Sherlock Holmes, very truly yours,

“Irene Norton, née Adler.”

The King practically swoons with admiration.

“What a woman—oh, what a woman!” cried the King of Bohemia, when we had all three read this epistle. “Did I not tell you how quick and resolute she was? Would she not have made an admirable queen? Is it not a pity that she was not on my level?”

“From what I have seen of the lady, she seems, indeed, to be on a very different level to your Majesty,” said Holmes, coldly. “I am sorry that I have not been able to bring your Majesty’s business to a more successful conclusion.”

“On the contrary, my dear sir,” cried the King. “Nothing could be more successful. I know that her word is inviolate. The photograph is now as safe as if it were in the fire.”

“I am glad to hear your Majesty say so.”

“I am immensely indebted to you. Pray tell me in what way I can reward you. This ring—.” He slipped an emerald snake ring from his finger, and held it out upon the palm of his hand.

“Your Majesty has something which I should value even more highly,” said Holmes.

“You have but to name it.”

“This photograph!”

The King stared at him in amazement.

“Irene’s photograph!” he cried. “Certainly, if you wish it.”

“I thank your Majesty. Then there is no more to be done in the matter. I have the honour to wish you a very good morning.” He bowed, and, turning away without observing the hand which the King had stretched out to him, he set off in my company for his chambers.

(One enjoys Holmes’ barely concealed contempt for the King. Indeed, throughout the tales Holmes is singularly unimpressed by titles. Consider how quickly he swats down a fat-headed aristocratic twit in ‘The Noble Bachelor’:

“Good-day, Lord St. Simon,” said Holmes, rising and bowing. “Pray take the basket-chair. This is my friend and colleague, Dr. Watson. Draw up a little to the fire, and we will talk this matter over.”

“A most painful matter to me, as you can most readily imagine, Mr. Holmes. I have been cut to the quick. I understand that you have already managed several delicate cases of this sort sir, though I presume that they were hardly from the same class of society.”

“No, I am descending.”

“I beg pardon.”

“My last client of the sort was a king.”

“Oh, really! I had no idea. And which king?”

“The King of Scandinavia.”

Snap! This disdain reflects that of Doyle, who grew up a Catholic outsider and was a self-made man; when offered a knighthood, the author only, reluctantly, accepted because of his mother’s insistence.)

So we come to the real understanding of Holmes’ admiration of Irene Adler. It has indeed nothing to do with emotion. Holmes feels the high regard a chess master feels for one who has bested him at the game; he acknowledges an intelligence at least equal to his, if not greater. From a narrative point of view, the turnabout at story’s end was a great surprise to the reader expecting a scheming hussy to get her just deserts from the great detective.

Nonetheless, one can discern in Irene Adler a type of woman who, at the end of the 19th century, was a source equally of admiration and of unease. Stars of the opera — Prima Donnas — and of the theatre, such as the legendarily wealthy and independent Sarah Bernhardt or her rival Eleanor Duse, held society enthralled even as they scorned its strictures, openly taking serial lovers. It was also the time of such famed courtesans as Cora Pearl and La Belle Otero. Irene Adler embodied these “adventuresses”, as they were called, and we can understand Dr Watson’s stuffy disapproval of her — ”the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.” (Note the “late”– Adler must be punished, if only offstage, with death.)

Taken even further, this dismay at free and sexually powerful women brought about the flowering of the image of the femme fatale, a deadly seductress all too ready to entice and vanquish men — consider the painting The Vampire by Munch, or Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé — originally written for Bernhardt, and published in 1893, the same year as ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ was. (Doyle knew and much admired Wilde.)

Yet, as noted, Doyle admired strong women like those who were then entering the masculine fortresses of the professions. In sum, ‘Scandal’ reflects the attitudes of an intelligent but conflicted man of his times.

(In the modern-day update of Holmes, the TV series Sherlock, the sexuality of Irene Adler is unfortunately much heightened, with shocking scenes of nudity. I apologise to the reader for the image of deplorable filth below, and assure you that I only post it with the greatest reluctance in order to illustrate the current age’s depravity.)

Brazen actress Lara Pulvar as Irene Adler in ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’.

The full text of ‘A Scandal in Bohemia can be found here.

‘Scandal’ isn’t the only case in the Holmesian canon to find a woman besting him intellectually. Consider ‘The Adventure of the Yellow Face’. (More spoilers ahead.)

Mr Grant Munro, of Norbury, consults Holmes on his wife Effie’s strange behavior. She surprises him with a request for a hundred pounds; she seems to keep visiting a mysterious nearby cottage, at the window of which Munro spies a grotesque face of a ghastly yellow hue. Despite his entreaties and her promises he cannot keep Effie away from the cottage, nor will she explain the mystery. At wit’s end he has come up to London to consult Holmes, who interprets the story thus:

“The facts, as I read them, are something like this: This woman was married in America. Her husband developed some hateful qualities; or shall we say that he contracted some loathsome disease, and became a leper or an imbecile? She flies from him at last, returns to England, changes her name, and starts her life, as she thinks, afresh. She has been married three years, and believes that her position is quite secure, having shown her husband the death certificate of some man whose name she has assumed, when suddenly her whereabouts is discovered by her first husband; or, we may suppose, by some unscrupulous woman who has attached herself to the invalid. They write to the wife, and threaten to come and expose her. She asks for a hundred pounds, and endeavours to buy them off. They come in spite of it, and when the husband mentions casually to the wife that there are new-comers in the cottage, she knows in some way that they are her pursuers.[…]”

Homes, Watson and Munro go down to Norbury, where they bully their way into the cottage, and find Effie in the company of a dwarfish figure with a hideous yellow face:

An instant later the mystery was explained. Holmes, with a laugh, passed his hand behind the child’s ear, a mask peeled off from her countenance, and there was a little coal black negress, with all her white teeth flashing in amusement at our amazed faces.

Effie produces a locket, and shows them the portrait inside of a light-skinned African-American:

“That is John Hebron, of Atlanta,” said the lady, “and a nobler man never walked the earth. I cut myself off from my race in order to wed him, but never once while he lived did I for an instant regret it. It was our misfortune that our only child took after his people rather than mine. It is often so in such matches, and little Lucy is darker far than ever her father was. But dark or fair, she is my own dear little girlie, and her mother’s pet.[…] And now to-night you at last know all, and I ask you what is to become of us, my child and me?” She clasped her hands and waited for an answer.

Art by Sidney Paget

It was a long two minutes before Grant Munro broke the silence, and when his answer came it was one of which I love to think. He lifted the little child, kissed her, and then, still carrying her, he held his other hand out to his wife and turned towards the door.

“We can talk it over more comfortably at home,” said he. “I am not a very good man, Effie, but I think that I am a better one than you have given me credit for being.”

A sweet conclusion indeed; one that shows the mighty detective’s intellect once more outsmarted by a woman, as Holmes himself ruefully ackowledges in the tale’s final lines:

“Watson,” said he, “if it should ever strike you that I am getting a little over-confident in my powers, or giving less pains to a case than it deserves, kindly whisper ‘Norbury’ in my ear, and I shall be infinitely obliged to you.”

The full text of ‘The Yellow Face’ can be found here.

The attitude towards a racially mixed marriage was astonishingly progressive for 1893. Doyle was an anti-racist, the result of a voyage he made to West Africa in 1881 as ship’s doctor on the steamer Mayumba. At first he evinced the depressingly normal Imperialist bigotry of the age against “savages”. But the more he came in contact with the local natives, and with the riff-raff whites who lorded over them, the more he was convinced that the British and other colonisers should leave the Africans alone. Doyle also struck a friendship that seems to have definitely turned his views on race: for three days the Mayumba carried as a passenger the American Consul to Liberia, a Black man named Highland Garnet. Garnet had been born into slavery in 1815. He was a militant abolitionist, an author and educator and public servant of great culture. Those three days of conversations were a revelation to Doyle, and shaped his views of race for a long time.

Not, alas, for all his life. Like many people, Doyle seems to have become more reactionary with old age. ‘The Yellow Face’ dates from 1893; ‘The Adventure of the Three Gables’ from 1927, and how great the fall from the first to the second. It features a repugnant caricature of a Black thug…

The door had flown open and a huge negro had burst into the room. He would have been a comic figure if he had not been terrific, for he was dressed in a very loud gray check suit with a flowing salmon-coloured tie. His broad face and flattened nose were thrust forward, as his sullen dark eyes, with a smouldering gleam of malice in them, turned from one of us to the other.

…who speaks in blackface:

“Which of you gen’l’men is Masser Holmes?” he asked.

…makes brutish threats:

He swung a huge knotted lump of a fist under my friend’s nose. Holmes examined it closely with an air of great interest.

“Were you born so?” he asked. “Or did it come by degrees?”

Holmes wastes no time insulting the insolent darkie in the vilest terms:

“I’ve wanted to meet you for some time,” said Holmes. “I won’t ask you to sit down, for I don’t like the smell of you, but aren’t you Steve Dixie, the bruiser?”

“That’s my name, Masser Holmes, and you’ll get put through it for sure if you give me any lip.”

“It is certainly the last thing you need,” said Holmes, staring at our visitor’s hideous mouth. “

Holmes easily browbeats Dixie into cringing submission.

“So help me the Lord! Masser Holmes –”

“That’s enough. Get out of it. I’ll pick you up when I want you.”

“Good-mornin’, Masser Holmes. I hope there ain’t no hard feelin’s about this ‘ere visit?”

When Dixie scurries out, Holmes enjoys a good racist chuckle with Watson.

“I am glad you were not forced to break his woolly head, Watson. I observed your manoeuvres with the poker. But he is really rather a harmless fellow, a great muscular, foolish, blustering baby, and easily cowed, as you have seen.[…]”

The full text of ‘The Adventure of the Three Gables’ can be found here. I don’t recommend it; even apart from the naked bigotry, it is a weak story.

In order not to end this article on a sour note, let us return to ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ and its last lines:

And that was how a great scandal threatened to affect the kingdom of Bohemia, and how the best plans of Mr. Sherlock Holmes were beaten by a woman’s wit. He used to make merry over the cleverness of women, but I have not heard him do it of late. And when he speaks of Irene Adler, or when he refers to her photograph, it is always under the honourable title of the woman.