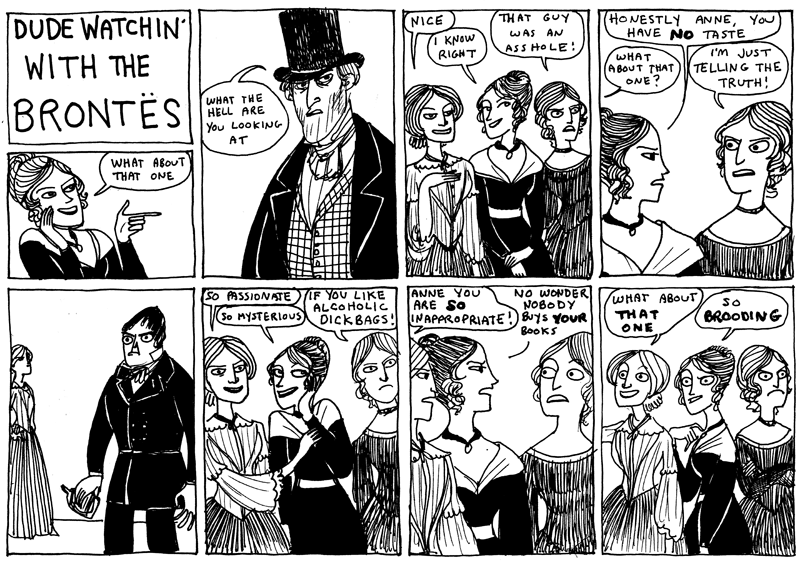

I think the above cartoon by Kate Beaton is the first piece of Anne Bronte criticism I ever saw. At the time, I hadn’t read any of Anne’s novels, but the cartoon certainly made me think I should.

Well, I finally have…and as it turns out, I’m not sure I entirely agree with Beaton. The cartoon is obviously focused on The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, which is centered around the abusive marriage of Helen and Arthur Huntingdon.

Certainly, in comparison to the brutish protagonists of Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights, Arthur is much less romanticized — or really not romanticized at all. He is not brooding or exciting, but (as Anne says in the cartoon) an asshole dickbag, whose good looks and charm conceal wells of selfishness and cruelty. He’s a drunkard, a cad, and an adulterer, who treats his wife with indifference and contempt (leaving her alone for months at a time so he can carouse in London) and then terrorizing her when she protests. He deliberately tries to get his young child to drink and curse to amuse himself and his friends. His low point comes when he discovers that Helen is planning to leave him and support herself by painting; he storms into her room, takes all her money, and destroys her painting materials.

Much of the novel, then, is a harrowing description of a domestic tyrant, and an unflinching portrait of the powerlessness of married women at the time. Helen has no rights to divorce her husband, even though he is basically parading his mistresses in front of her; she can’t take the child away from him, though he is deliberately, and basically out of spite, attempting to corrupt him. Moreover, her early attempts to reform her husband founder precisely on the disproportion of their power; she has no means under law or custom to influence him; she can’t even make him stay in the same house with her, or make decent efforts to conceal his adultery. The romantic notion that a good woman can save a bad man (very much in play in Jane Eyre, for example) is shown to be not so much spiritually as logistically impossible given the status of women at the time.

So far as Arthur Huntingdon is concerned, then, so good. But, unfortunately, the book feels compelled to present us with another suitor for Helen. And so we get Gilbert Markham, the epistolary narrator of much of the novel. Markham is a gentleman farmer, and the most eligible young bachelor in the neighborhood into which Helen moves after escaping from her husband. She and Gilbert quickly strike up a relationship, which eventually ends in married bliss after Huntingdon obligingly drinks himself to death.

And again, this is unfortunate because, contra Beaton, Gilbert is kind of an asshole. Oh, he’s vastly superior to Huntingdon; he’s not a drunkard or a monster. But that’s a pretty low bar. Without Huntingdon for comparison…well, he doesn’t come off so well. He’s conceited, petulant, and selfish; he toys with the affection of a neighboring clergyman’s daughter, and then tosses her aside when he decides that Helen is more interesting — and when said clergyman’s daughter is upset and resentful, he blames it on the failings in her character and essentially accuses her of being a shallow designing flirt.

Nor is his treatment of Helen much better. He sneaks onto her property and oversees her embracing another man, Frederick Lawrence. Rather than asking her to explain the situation, he rushes off and refuses to speak to her. He also loses his temper and a few days later assaults Lawrence, seriously injuring him and confining him to his bed for several days.

So, to sum up, Gilbert is a jilt, a sneak, and a thug, petulant, cruel, and thoughtless. And yet, he’s supposed to be the good guy!

Of course, Gilbert’s courtship of an sympathy with Helen, and his discovery that Lawrence is Helen’s brother and that in assaulting him he behaved like a total poltroon — all those things are supposed to make him a better, less impulsive, more caring person, and a fit husband for Helen. But that’s not a contradiction to the assholes-are-cool-so-marry-one narrative. Rather, it’s the same narrative over again. You’ve got your infantile ass with anger management issues, and instead of saying, you know, I don’t really want to marry an infantile ass with anger management issues, you end up saying, hey! It’s a fixer upper! Awesome!

There’s at least one other fixer uppers in the book too — one of Huntingdon’s carousing buddies ends up being transformed into a doting husband through the power of his wife’s love (with a little nudge from Helen.) One might be an accident, but two starts to look like carelessness. It’s great that there are some levels of brutality and drunkenness that Anne is willing to be repulsed by…but I think Beaton goes a little too far when she ask rhetorically:

Anne why are you writing books about how alcoholic losers ruin people’s lives? Don’t you see that romanticizing douchey behavior is the proper literary convention in this family! Honestly.

Anne’s perfectly capable of romanticizing douchey behavior. She’s perhaps tweaking the family literary convention, but she’s not rejecting them. If you want a guy who treats women with respect, you need to read Jane Austen or E.M. Forster or maybe watch Say Anything. With the Bronte’s, the best you can hope for is a slightly smaller asshole.