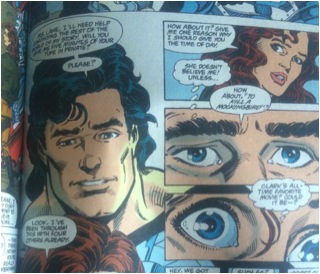

This scene from Superman vol.2 #81 takes place near the end of the “Reign of the Supermen” storyline, which was the final third of the “Death and Return of Superman” saga from 1993. In it, the real Superman has returned and convinces Lois Lane of his identity by quoting the last thing he said to her before rushing off to his death at the hands of the villain Doomsday. First, though, he references his favorite film. While this serves as a piece of trivia for the character, it also reaffirms the intrinsic nature of Superman, and what he values most as a “Champion of the Oppressed”.

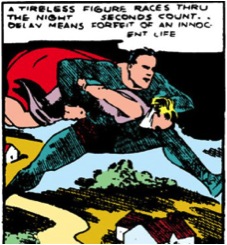

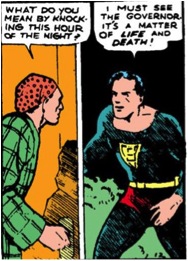

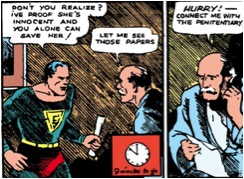

Superman’s status as a defender of the little people was immediately established in his first appearance in Actions Comics #1. The opening scene has Superman using his extraordinary powers to save a woman wrongly convicted of murder, and to put the real killer behind bars.

At every moment of opposition, Superman refuses to let anything stand in his way and barrels through the likes of an armed butler and steel doors in order to set things right, spouting one-liners like “It was your idea!” after meeting the butler’s dare to knock down a steel wall.

This adventure, the first of three in the title’s premiere issue, serves as the perfect debut for the Siegel and Shuster Superman. Righter of wrongs, defender of democracy, this Superman fought everything from drunk drivers to the Ku Klux Klan to Adolf Hitler himself, in one form or another. It’s interesting to me that the very first superhero, the one whom all others would take inspiration from, was in his origins almost totally divorced from the confines of the superhero genre as it’s come to be known. Bring up a costumed crime fighter to an average person who doesn’t read comics, and they’ll imagine someone in a goofy suit with powers stopping a bank robber with an equally goofy suit and powers, with a silly name to go along with it. Hardly ever does a comic hero’s adventures address social injustice, and when they do it’s always presented ostentatiously. In this context, Superman’s roots as a fighter for social justice have been obscured, though not lost entirely.

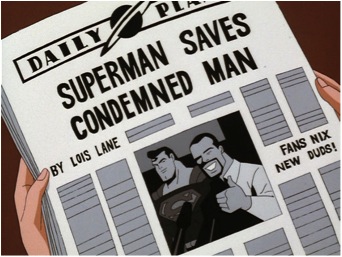

One story that focused on Superman pursuing social justice is the best episode of the 1996 Superman animated series. “The Late Mr. Kent”. In this story, Clark Kent is presumed dead after a car bomb goes off while he’s in the process of clearing a wrongly convicted man days before his execution.

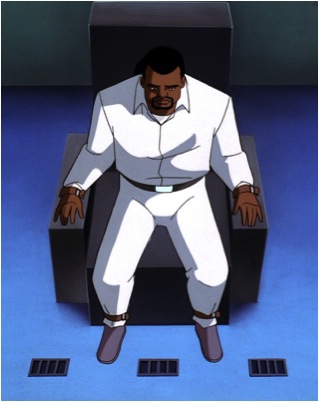

While this episode is rightly lauded for its taut direction, film noir atmosphere and insight into the mind of Clark Kent as opposed to Superman (to reference an age-old debate), one thing that never gets brought up is the racial themes that are implicitly addressed. The man, Earnest Walker, is a low-level thief who has been on death row for five years for murdering a woman and is now scheduled for the gas chamber. He claims to the interviewing reporter, Clark Kent, that he’s never hurt anyone in his life, and found the victim’s necklace outside his door and fenced it, concluding that he was framed. Right away Clark senses a calm heartbeat and figures he’s telling the truth. When Clark begins to investigate, everyone from the police detective to Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen maintain Walker’s guilt. Later when Clark researches Walker’s alibi of eating pizza at home, he learns that this went uninspected by his public defender.

Clark finds Walker’s alibi on the Pizza Delivery company’s record disk and drives to the governor’s mansion, at which point his car explodes. With a witness seeing his car fly into the ocean, the dilemma of exposing his identity to save Walker’s life comes into play. After flying by his adoptive parents’ home and secretly attending his own funeral as Superman, Clark decides to explain the situation to the governor, secret identity be damned.

Of course that doesn’t happen, and the revelation of who’s behind the conspiracy soon arrives. At the end of the episode however, Superman is too late to stop the governor from attending Walker’s execution, so he bursts through the chamber and sucks the gas out into the sky where it disperses. The attending crowd is initially horrified at Superman’s sudden act of random destruction.

This takes the Siegel and Shuster story one step further, proving Superman wrong when he said that only the governor could save the condemned woman. This Superman doesn’t loudly boast threats or crack jokes at his opponent’s expense. He maintains a quiet resolve. Earlier in the episode he admits to himself that he wanted the exoneration of Walker to be a victory for Clark Kent and not Superman, yet he came to his decision to reveal his identity on his own.

In this, Superman is Atticus Finch in animated form. Nowhere do we see any sort of vaudeville comedy act with the Clark Kent persona differentiating the Superman persona. Like Miss Maudie says of Atticus, Superman is the “same in his house as he is on the streets”. The same quiet dignity that is often ascribed to Atticus can be found in Clark’s patient inquiries to Detective Bowman and the Pizza worker. He seeks justice to the best of his ability, first through his job as a reporter, then as Superman with the knowledge that his double life will come to an end should he further pursue Walker’s freedom. Whereas Atticus at his best failed to win Tom Robinson his freedom and ultimately save his life, Superman at his best brought the slain woman’s killer to justice and cleared Walker’s name.

Ultimately the episode ends with nowhere near as substantial a statement on race as To Kill a Mockingbird did. As I said before, virtually no one has commented online or on the series DVDs about the fairly visible comment on wrongful arrests and executions. To have it addressed in a Superman cartoon couldn’t have been a complete accident however. Although I highly doubt it was done as a roundabout way to tie in to the reference of Superman’s favorite film in the comics at the time, the social justice angle of the episode is too explicit to ignore. While the character would see a return to his roots as a “Champion of the Oppressed” in the pages of Action Comics vol.2 written by Grant Morrison, I like the more measured approach taken here. It feels more resonant and important to have Superman saving wrongly convicted black guys rather than kicking rich businessmen into street lamps. It teaches us, however obliquely, to oppose racial bias and always try to help the less fortunate. It’s a way to have us learn from Superman’s example, in the same way that Atticus Finch had us, and Superman, learn from his example.