So the critics like it, they really really like it.

Poor old Batman v Superman (RT Score 28%) is sitting in the corner sucking his thumb as Captain America does his victory jig and Iron Man shakes his buttocks in delight.

But at least BvS didn’t put me to sleep which is more than I can say for Captain America: Civil War. I spent the first hour of the movie fighting back the urge to take a nap and I almost never fall asleep while watching movies at the theater. Yet how are we to fathom this when the Grand Lodge has determined the vast superiority of Civil War (RT Score 94%)?

I think it’s fair to say that the only thing worse than a comics critic is a movie critic, at least as far as standards are concerned. At The New Republic, Will Leitch swoons over Joss Whedon and Jon Favreau as if they are demi-gods of celluloid, proclaiming them “terrific four-quadrant filmmakers.” In the very same breath, he suggests that Civil War can’t stand up to the two previous Avengers movies but is awesome nonetheless.

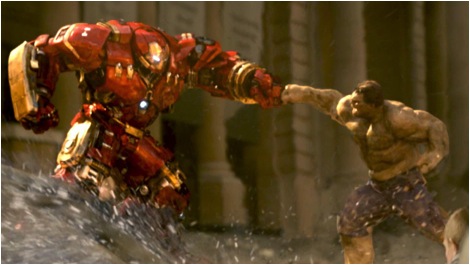

I’m sometimes seen as a harsh critic but saying that a movie is worse than Avengers: Age of Ultron is nothing short of farting pointblank into someone’s face. I cringe in horror whenever I think of Whedon’s farm house scene from Ultron especially when I remember how Whedon supposedly fought tooth and nail for its inclusion and considers it the epitome of his superhero aesthetic—in other words shallow, fannish, unnecessary, and dumb.

At the New Statesman, Ryan Gilbey gushes uncontrollably and announces that, “Civil War is the “antidote to Batman v Superman’s poison for comics fans.” Speaking as a comic fan, I think Marvel-Disney has done an exquisite job of poisoning comics and pissing on its grave but let’s not quibble over the finer points. Here’s the best part of Gilbey’s review:

“The plot is so satisfyingly worked out, and the foundations for the hostilities in the second half of the film so carefully prepared, that you want to take aside the makers of Batman v Superman (who thought it was motivation enough just to have one superhero mistakenly believe that the other was running amok) and say to them: See? This is how it’s done. It’s not so hard, is it?”

It helps also that there is nuance and colour here. The characters are multi-layered, crammed full of old allegiances and grudges and irritations. They have personalities. Remember those?”

I don’t know Mr. Gilbey, I agree that Batman v Superman isn’t made of the brainiest stuff (maybe it needs to be retained a year or two) but having two opposing superhero groups decide to wreak havoc across continents because Steve Rogers doesn’t want to sign a UN contract and just wants to protect his mass murdering pal (Bucky) does seem like rather poor motivation compared to seeing all your friends and colleagues killed by two superpowered Kryptonians.

And, no Mr. Gilbey, despite being the characters with the most lines in the movie, Captain America and Iron Man do not actually have “mutli-layered” personalities. They both speak in clichés, are one note cardboard caricatures, and barely have time to articulate a single serious idea; largely because they spend 50% of the movie beating people up, and a solid 25% of their waking hours cracking jokes while destroying public property.

But Gilbey is as nothing compared to the Uber Marvel fanboy, Justin Chang, writing in Variety:

“The shaming of Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice will continue apace — or better still, be forgotten entirely — in the wake of Captain America: Civil War, a decisively superior hero-vs.-hero extravaganza that also ranks as the most mature and substantive picture to have yet emerged from the Marvel Cinematic Universe.”

Now I’m happy for Batman v Superman to be buried and forgotten as long as its tentacles reach out from the deepest nether regions and pulls every single Marvel movie down with it as well. What a wonderful world that would be. No more Superhero Movies as the Scarlet Witch once said. Chang continues:

“And the sides-taking showdown between Team Captain America and Team Iron Man, far from numbing the viewer with still more callous acts of destruction, is likely to leave you admiring its creativity.”

So let me see, would this lack of numbing callous destruction also include the part where the Avengers destroy parts of Lagos, a Berlin airport, and some unimportant city where the Winter Soldier is camping out? I guess it’s all less “numbing” because only Marvel superheroes ravage foreign lands with a smile. Chang is so clearly invested in these idiotic characters that it’s pure comedy to see him turn the joyless lives of Tony Stark and Steve Rogers into Ingmar Bergman Spandex hour. But he continues:

“In assembling this Marvel male weepie, scribes Markus and McFeely show a rare talent for spinning cliches into artful motifs: The pain of deep, irrecoverable loss recurs throughout the narrative, and for both Iron Man and Captain America, the bonds of friendship are shown to run deeper than any commitment to the greater good.”

In other words, Civil War is 3-Kleenex movie: one for when you feel the bile emerging from your stomach, the second for when you spit on the ground in disgust and have to clean up after yourself, and the third for when you finally fall unconscious and someone needs to wipe the dribble from mouth. But let’s talk about that “deep, irrecoverable loss” shall we?

The most affectionate moment between Tony Stark and his parents (the great motivator of the movie’s final fist fight) occurs near the start of the movie where the audience is abused with some godawful CGI which turns Robert Downey into some pasty refugee from Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf. Seeing this in IMAX 3D did not help one bit. Tony then emotes to a lecture hall full of MIT students about his exquisite feelings of loss before handing out grant freebies to them all. Voila! Instant emotion and reason for knocking the crap out of Captain America. I guess when you’re shot up with the Marvel Super Critic serum, you don’t really need to see and hear the loss to feel the loss. You can just get it by telepathy, presumably from the rotting corpse of Walt Disney.

These are frightening people, folks. They want to convince us that the doggie doo in the apple pie is good for you. But there’s still some butter in the crust. I think it’s possible to see Civil War as a kind of Dr. Strangelove style satire without the bite; all hidden in plain sight with the umbral subtlety of a Dick Cheney.

The fact is, the protagonist of the show (Captain America for those not paying attention) encapsulates the true American Spirit of derring-do and humanitarian intervention. Chris Evans is dressed in primary colors unlike our bespectacled madman, Peter Sellers, but he’s a true psychopath of near Tom Cruise-ian Mission Impossible levels.

When someone tells Cap not to break things, he lets them know that he has to because it’s his Responsibility to Protect; he has to burn the village to save it. He has no interest in the judicial system since it’s run by military madmen just like himself. Like a true villain, his loyalty to Bucky overrides all moral and ethical responsibilities. Logic isn’t his strong suit, he just needs his freedom because his Democracy of One is indubitably best suited to the practice of ecstatic violence. The true heart of the movie is that Captain America wants to save a world that doesn’t need to be saved; a world that was never in any danger in the first place. The real hero of Civil War is Baron Zemo who has engineered a preposterous scheme to get Cap and Iron Man to fight each other and disassemble the Avengers (if they don’t kill each other first) so that the world will be saved from Marvel movies. He’s the Ozymandias of Civil War and, of course, he fails; doomed to watch reruns of Bambi in his jail cell for the rest of his days.

Even the Captain America of the comics turned himself in after a while and got himself killed, but this isn’t an option for the Steve Rogers of the movies since he’s probably all ready to do battle in Marvel’s upcoming Infinity War. Hopefully they’ll just kill him off when the Marvel movie universe starts tanking (just like the superhero pamphlets) some years down the road. Nothing lasts forever…I hope.