Seconding other contributors that I don’t go out of my way to read comics I don’t like, so for this roundtable I had to reach back – way back – to when I’d read anything.

You know how it is: you read comics with your friends, and you’re all willing to spend more time on the things you don’t like – maybe because you haven’t worked out how to tell yet, within the first couple chapters, when a series is going to the dogs. Or maybe because you’re students or underemployed, with more time to spend on stuff that’s bad (in an interesting way) as well as on stuff that’s good. Or maybe because your friends are like me and mine, a bunch of fanfiction writers who are drawn to flawed art like wolves to wounded prey.

Not this kind of wolf, obviously

In any case, I don’t hate these flawed comics (or manga). Rather, I am fond of them: because they were good enough at the time, because even the bad ones were entertaining, and because I read them as a part of a community that didn’t expect perfection – and actually, probably, preferred some flaws in the first place.

So why read something you hate – I mean really, truly hate? Because you didn’t know you would hate it? Because other people – the in-crowd, the public – love it? Because the people who matter – your friends, critics you respect – love it? Or maybe because in another lifetime, you might have loved it too?

Though there are exceptions, it seems to me that very often, to hate something you also have to love it. A series you “hate” in this way is a series you would have loved, if it wasn’t for this one, specific, terrible thing that you hate. That’s the kind of hate I’ll be talking about in my article about Bakuman.

Bakuman is the second manga series by writer-artist pair Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata, who previously worked on Death Note together. Death Note was a mess by the end – and morally challenged from the beginning – but I have fond memories of it since it was the first manga series I got really into with other people on the internet.

There was so much bad faith moralizing in that series. A single sociopath high school student was going to make the world a better place by killing already-apprehended criminals, who were waiting in jail for their sentences to be decided, using a magic notebook. This would deter other criminals from committing crimes, leading to a better, crime-free world. Because it’s the countries that have a transparent, (semi-)functioning justice systems and active, (semi-)free cultures of journalism, that report on crime and imprison criminals according to the rules of law, that are the worst off, am I right?

The thing is, while Death Note did a pretty good job of painting Light, the megalomaniacal serial killer high school honors student who lucks into the possession of an instrument of mass murder, in a negative light (because power corrupts and only the corrupt seek power), it didn’t really have many characters who were much better – who were morally upright and competent. When a character with brains and morals did show up, s/he was first brought down below even Light’s level (supporting torture, for instance), or else shown up by Light, and then killed. And more importantly, Death Note never really questioned whether Light’s “plan” to become “God” of the “new world” would work. If you are smart, you are better than the system, but when you exercise that superiority, you become a monster, the series suggests. The System eventually catches up with you and kills you, justice is served, the end.

It’s not a spoiler because the series had to end this way.

But I don’t hate Death Note. In its own way, it’s an interesting morality story, or at least an interesting look into Ohba’s twisted mental landscape. It’s also a work of the zeitgeist, tackling – among other themes – Japan’s 2004 shift from trial by judge to trial by jury (see below) and whether torture can ever be justified. You can also, if you squint, see some questions about memory and identity, as Light becomes a very different person during the brief period when his memories of the Death Note are removed.

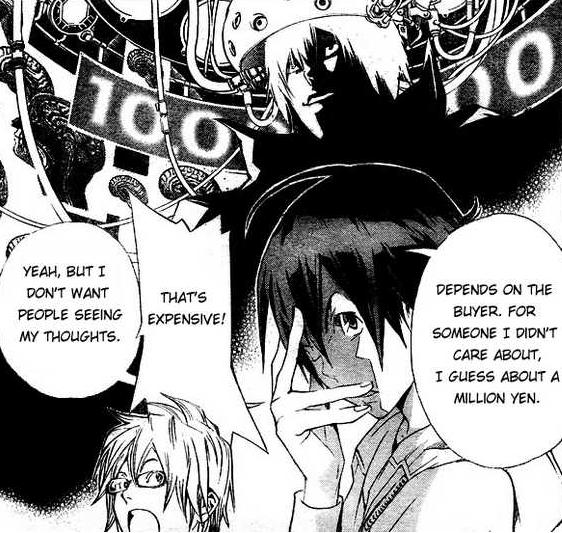

Japan’s shift to a lay jury system was also tackled by absurdist Nintendo DS series Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney, now a live action movie directed by Takahashi Miike

We don’t know very much about Death Note author Ohba, other than that he – or she – is a bit OCD, draws him/herself as a woman on the album sleeves, and is rumored to be a well-known novelist when not moonlighting as a rookie manga author. Obata, meanwhile, is a very well-known artist, having previously illustrated Yumi Hotta’s critically acclaimed manga Hikaru no Go and worked as an assistant under Nobuhiro Watsuki on fan-favorite Rurouni Kenshin. Death Note’s success, as a comic and not a vehicle for Ohba’s wacky ideas or convoluted plots, is no doubt down to Obata, who reportedly handled most of the character designs and, especially in later volumes, the page layouts. In a comic where everyone either agrees with the hero or is hopelessly naïve – or is pursuing a private agenda – Obata’s distinctive character designs help to make every character unique and identifiable.

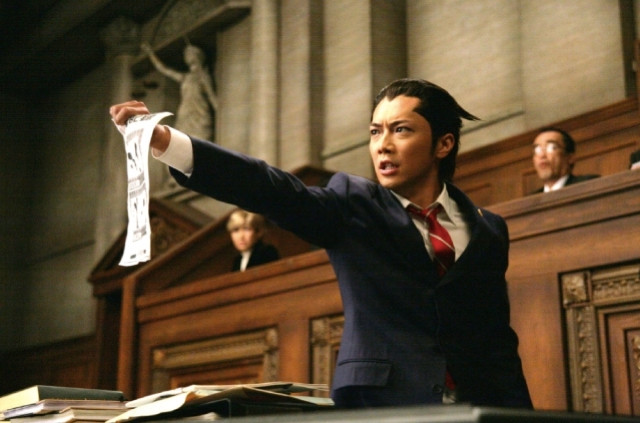

And he has great fashion sense, too

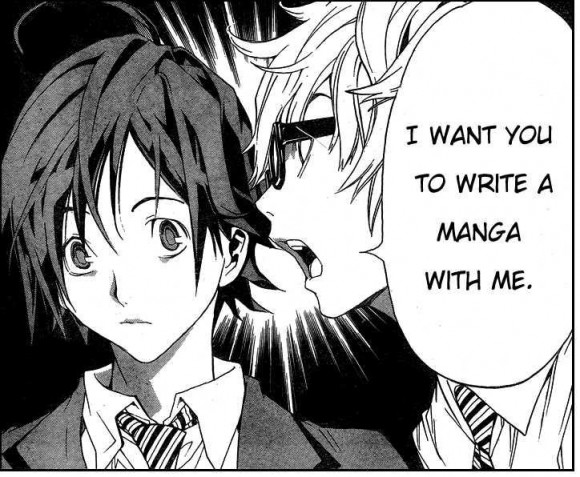

Flash forward to Bakuman. In an Ouroboros-like plot, this is a manga about making manga. The protagonists, childhood friends Moritaka Mashiro and Akito Takagi, are an artist-writer pair just like Obata and Ohba. They share a dream, of being published in Shonen Jump (the magazine that serialized Death Note and Bakuman), coming in #1 in the reader popularity polls, and having their comic adapted into an anime, at which point Moritaka’s childhood crush will be cast in the title role and they can finally be together.

Moritaka and his future wife have a pure love. There are no Freudian implications here at all.

It’s exactly the kind of thing I really like. As in a lot of other exaggerated, but ultimately (mostly) non-fantastical shonen manga, you can learn something by reading Bakuman. In this case, you are not learning about bread, or wine, or shougi, or go, or American football; rather, you are learning how to become a famous mangaka for Shounen Jump. There’s a lot of actually very good behind the scenes analysis in Bakuman, covering topics like: how the popularity poll results are counted, how to submit work to a contest, what kind of work sells for what reasons, how to work with an incompetent editor, and how to hire and work with assistants. Just like in Hikaru no Go, you don’t get the sense that the protagonists are “ordinary” or that their rise to the top is easy. In Bakuman, Moritaka and Akito live and breathe manga. At one point Moritaka – still in middle school – is hospitalized for overwork, proving he is off to a good start in his professional career.

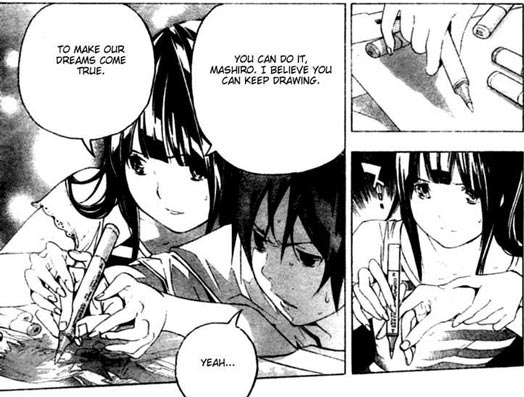

Adhering to the friendship! hard work! loyalty! Jump formula, with a few notable twists: two middle school boys in pursuit of their dreams

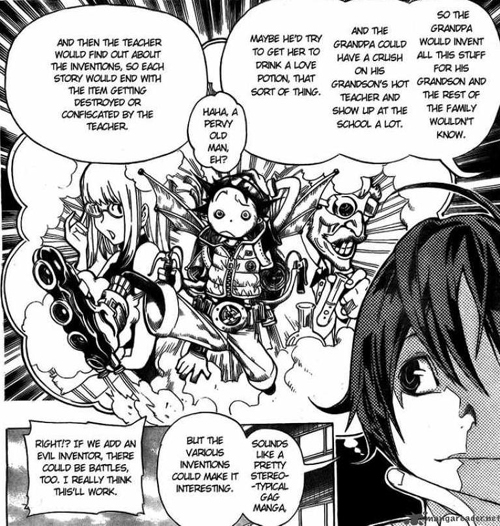

Just like in Death Note, the plot is fast-paced, with the first three volumes already covering three years. Ideas come fast and thick and in this case, have a natural outlet, as Moritaka-Akito work on countless series and toss out countless ideas that mostly all sound like they could be pretty good B-titles or short films. Other mangaka come on the scene, each with a separate and plausibly developed title. It’s a good showcase for Obata, who uses a different art style for each series-within-the-series, with his signature, realistic style reserved for the pair’s main series about an eccentric inventor, a hapless child, and a punishing female authority figure. There’s a bit of the “Theory of Mind” that was on display in Death Note – characters either agree with and support the main pair, or are irrational – but again, as in Death Note, the character designs are distinct and memorable, leading to an interesting and entertaining main cast.

Obata uses his signature realistic style the most when drawing the protagonists’ own manga

It’s not Shakespeare, but it’s a perfectly serviceable diversion, especially if you like inside-baseball comics about the business of making comics. The main pair are also immensely appealing as a pair, the kind of BFFs who have each other’s backs in business as well as in romance, and can finish each other’s sentences. Who doesn’t want a partner like that?

Then there’s the thing I hate: and that’s that Bakuman is really, really sexist.

You can sense the hand of an editor, somehow, in the introduction of the martial-arts-loving writer’s girlfriend, who karate-kicks him whenever he does or says something particularly outrageous. Subtle, no! But effective, yes! Women are, after all, 30% of Shounen Jump’s readership, so it wouldn’t make good business sense to insult them too much.

This is a panel from early on before, I suspect, an editor intervened to stem the damage. Or alternately, here’s Jog’s excellent analysis, including speculation that the sexism in this series is somewhat knowing.

It’s something, but it’s not enough. A partial list of Bakuman’s sexist and misogynist plot points might include:

–Marrying your girlfriend so she will shut up about the other girl who likes you (and whom you might like a little bit, too)

–Training a female mangaka in the art of catering to men: only in this way can her work be validated/successful

–General insistence that girls’ opinions don’t count, that only pretty girls matter, but that smart and pretty girls who don’t cater to men are actually “dumb” and unattractive

–To even out the balance, there is a plot arc involving the repulsiveness of a fat, slovenly, otaku male mangaka, who ignores his cute geek girl assistant to focus on a woman who is way out of his league. He gets what he deserves when both women reject him.

And on and on. While really bottom of the barrel guys have their characters dragged through the mud, too, there’s a clear, obvious line between the basic decency and grooming required of men, and the flawless beauty and sainthood required of women.

I’m just gonna like… leave this here.

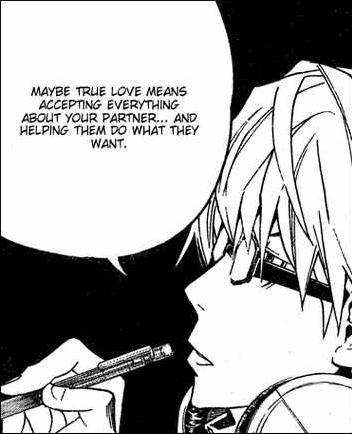

The funny thing about this is, while a lot of shonen manga series are passively sexist, in that they don’t have any strong or interesting female characters, Bakuman, because it is actively sexist and misogynist, paradoxically includes a lot more strong female characters – very beautiful, very smart women we are supposed to dislike for their “bad personalities” unless and until they prove they are willing to abase themselves to men. Thus, Akito’s karate-loving girlfriend is eventually tamed, and puts Akito first in everything. Once he is engaged to her, she can’t question his feelings for other women, and she can’t have goals beyond the promotion of his career.

Perhaps true love means accepting me even when I am a jerk to you?

Or there is Moritaka’s future wife, a pure and distant paragon of virtue, who proves her goodness when she turns down an offer to undress to further her acting career. Or Aoki Ko, the female author of a respected shoujo series, who for some inexplicable reason submits herself to the boys’ club at Jump. She’s smart, pretty, and humble, but she can’t be any good until she learns how to pander to the male readers.

Although OTOH, the idea of being “trained” in the manly art of drawing panty shots is admittedly pretty funny.

The thing is, a bunch of these issues are real issues for women. When’s the last time you saw a boys’ comic address rampant sexism within the industry (and within the voice-acting industry, as well)? Or the struggles of women in a sexist society?

These issues are addressed in Bakuman, but not from a place of love and understanding. More from a place of contempt and loathing. I haven’t read until the end of the comic, so it’s possible that the series does turn itself around. But I doubt it! There are just too many clues that Ohba and/or Obata really mean it.

In the final analysis, Bakuman is one of those series I would really love, if it wasn’t for this one specific thing that I hate. I think that makes it a pretty good candidate for this week’s roundtable.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.