Prosecuting former administrations for crimes divides us from our friends, encourages our enemies, and distracts us from the pressing and difficult business of governance. As one high-ranking government official said of a liberal reformer bent on raking up the crimes of the past, “He’s just handing the sword to others, helping the tigers harm us.”

As the poetic idiom suggests, the high-ranking government official was not Dick Cheney — it was Chairman Mao. And the liberal reformer in question was not Glenn Greenwald; it was Khrushchev.

I recently read William Taubman’s massive biography Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, and the book was on my mind as I paged through Glenn Greenwald’s new volume With Liberty and Justice for Some: How the Law Is Used to Destroy Equality and Protect the Powerful. The parallels are fairly obvious. Greenwald argues that American elites have effectively and deliberately placed themselves above the law. Illegal activity by the wealthy or powerful — Nixon Watergate crimes; Reagan Iran-contra crimes; Bush-era illegal wiretapping and torture; Wall Street malfeasance which led to the financial collapse — is not so much ignored as deliberately sanctified. Democrats, Republicans, and the press corps all agree that prosecuting the powerful would be divisive and hurt America. Therefore, as Obama has often said, “we need to look forward as opposed to looking backwards.”

Mao, obviously, felt the same way about Stalin. So, for that matter, did many in the Soviet hierarchy. These people weren’t idiots; they had good reason not to want to expose the extent of Stalin’s crimes. Communism had many enemies, both internal and external. For those enemies open discussion of the hideous mass killings of the Stalin era would be a propaganda coup. Moreover, Stalin’s heirs were all implicated in his atrocities. Mao in China was, of course, wading through shoals of decaying bodies, and was using Stalin’s personality cult as a blueprint for his own. The Russian elite was more directly involved; all had, at Stalin’s behest, consigned innocent people to death; all had failed to speak out to protect the innocent. Khrushchev, who succeeded Stalin, had certainly signed death lists.

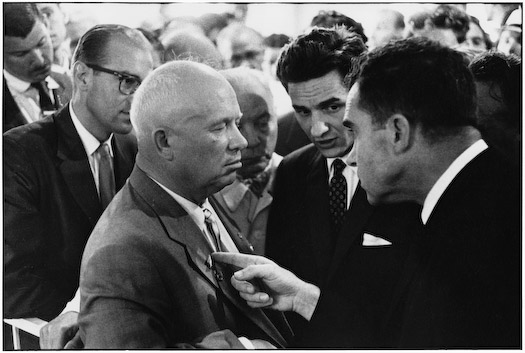

Yet, despite his own culpability, Khrushchev denounced his predecessor. Taubman in his biography calls this denunciation, delivered in a four hour speech, “the bravest and most reckless thing [Khrushchev] ever did.” It was certainly a braver thing, by many orders of magnitude, than any public act committed by Barack Obama, or by George W. Bush, or, for that matter by Clinton or even the sainted Reagan. We tend to think of Soviet rulers as absolute dictators who can govern with impunity, but the truth is that Khrushchev’s position at the top of the hierarchy was by no means entirely secure, and his decision to out Stalin’s crimes was a major political gamble. Taubman describes the reaction to Khrushchev’s speech, delivered in secret to the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in 1956.

Many in the audience were unreconstructed Stalinists; those who had denounced former colleagues and clambered over their corpses suddenly feared for their own heads. Others, who had secretly hated Stalin, couldn’t believe his successor was joining their ranks. As the KGB chief-to-be Vladimir Semichastny remembered it, the speech was at first met with “a deathly silence; you could hear a bug fly by.” When the noise started, it was a tense, muffled hum. Zakhar Glukhov, Khrushchev’s successor in Petrovo-Marinksky near Donetsk, felt “anxious and joyous at the same time” and marveled at how Khrushchev “could have brought himself to say such things before such an audience. ” Dimitri Goriunov, the chief editor of Komsomolskaya Pravda, took five nitroglycerin pills for a weak heart. “We didn’t look each other in the eye as we came down from the balcony,” recalled Aleksandr Yakovlev, then a minor functionary for the Central Committee Propaganda Department and later Gorbachev’s partner in perestroika, “whether from shame or shock or from the simple unexpectedness of it, I don’t know.” As the delegates left the hall, all Yakovlev heard them uttering was “Da-a, da-a, da-a” as if compressing all the intense, conflicting emotions they felt in the single, safe word, “yes.”

Of course, George W. Bush is not Stalin. Stalin caused the death of millions, and ordered I don’t know how many innocents tortured to death (thousands? tens of thousands?). Bush’s aggressive (and therefore, by international law, illegal) war in Iraq killed only in the low hundreds of thousands according to most estimates. Greenwald says the torture Bush authorized probably resulted in the deaths of at most 100 people. Similarly, the Obama administration and its Democratic allies have much less to lose by exposing their predecessors than did Stalin’s followers. As Greenwald points out, Democratic muckety-mucks like Nancy Pelosi and Jay Rockefeller were informed of Bush torture tactics and illegal wiretapping, which makes them complicit under the law. But they weren’t murderers like Khrushchev, and they haven’t just lived through a political bloodletting like the purges. If worse came to worse, they would only get jail time, not execution following a quick show trial.

These comparisons, though, do not necessarily redound to the credit of our political class. Khrushchev exposed Stalin-era crimes even though he had much more to lose by doing so than Obama has to lose in exposing Bush’s. Even in terms of national security, Khrushchev was in a significantly more precarious position. The U.S. has al-Qaeda to worry about; the Soviet Union had the U.S.— and, many, many other enemies, all much more credible as existential threats than Osama bin Laden could ever hope to be even in his most megalomaniacal wet dreams.

In fact, Khrushchev’s deStalinization damaged the Soviet Union in the short term, and arguably destroyed it in the long. The secret speech, which was at Khrushchev’s insistence duly publicized, sent shock waves through Soviet colonies in Eastern Europe. The Hungarian Revolution — which Khrushchev ruthlessly and bloodily crushed — was inspired in large part by the revelations of the true horror of Stalin’s reign. Khrushchev’s speech also alienated Mao, separating the USSR from one of its most important allies. Khrushchev’s anti-Stalinist rhetoric was used against him when he was forced from power in 1964, with one colleague declaring, “Instead of the Stalin cult, we have the cult of Khrushchev.” Even after Khrushchev himself was gone, his reforms continued to undermine the government and philosophy to which he had devoted his life. In the late 1980s, Khrushchev’s deStalinization became the blueprint for Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost, which ultimately caused the Soviet system itself to buckle.

So Obama and Mao aren’t wrong. Looking backwards can turn you into a pillar of salt. Exposing the crimes of the powerful really can delegitimize a government, and holding past rulers accountable really can have devastating consequences. To have faith in the rule of law, as Greenwald does and (vacillatingly, but nonetheless) as Khrushchev did, is to have faith in the system. It is to believe that democracy (or in Khrushchev’s case, socialism) is strong enough and vital enough to withstand the light of truth.

As it turned out, Soviet Communism wasn’t strong enough to withstand that light. Maybe our government isn’t either — in which case, the sooner we find that out, the better. Khrushchev’s deStalinization resulted in much misery for both himself and the country. But I don’t think anyone doubts it was the right thing to do.

Not that Khrushchev was a saint. On the contrary, he was a boorish, overbearing, often cruel man, with blood on his hands up to his elbows. But if we’re going to toss out the rule of law and model ourselves on tyrants, better him, by far, than Mao or Stalin.

__________________

This first ran on Splice Today.