“…all beings have a twofold face, a face of light and a black face. The luminous face, the face of day, is the only one that the common run of men perceive. Their black face, the one the mystic perceives, is their poverty The totality of their being is their daylight face and their night face”

-Henry Corbin

If, in the realm of human endeavour, there is one single activity which closely parallels or even mirrors the workings of identity, it has to be art. Art and the experiencing of art can define, describe, delimit, and categorize the personal in much the same way that identity does.

It should be no cause for wonder, then, that art and identity get conflated more often than not, with artist and spectator both viewing the engagement with art as integral to their personality.

Where this identification of art or culture with identity is a common occurence in the 21st century Occident, it has almost completely occluded a relationship that was previously of

immense significance- that between art and religion.

These days, inasmuch as identity, or the experience of the personal, is a prerequisite for the production of art, it should be unsurprising that much of contemporary spiritual or religious art lacks character. It is a risk of all art that genuinely and honestly seeks to express any sort of mystical experience; for the apex of the religious experience is a transpersonal one. It is exactly the direct transcendance of the limitations of selfhood which incapacitates the mystic to express that experience, for he lacks the personality to express it with. Like the captive shaman in Borges’ ‘La Escritura del Dios’ who discovers the secret name of God and the infinite power it would grant him, but who declines to use that power to escape his prison because the newly acquired infinite, cosmic vantage point makes him see the futility of his human desire to be free.

Perhaps art’s function has always been to express what is no longer there, to fix what moves onward in constant flux, to capture ghosts; thus to be, in a sense, non-being.

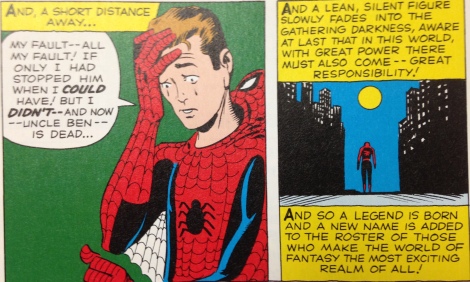

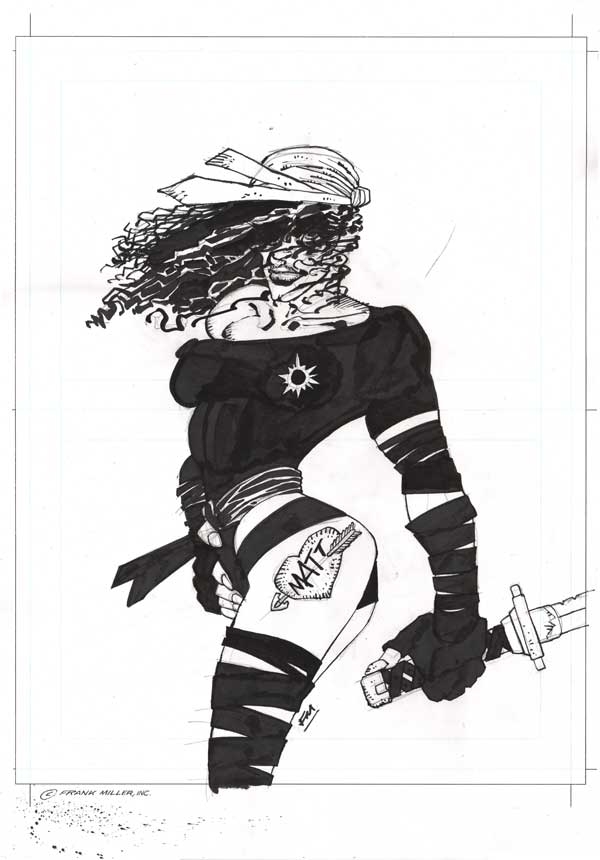

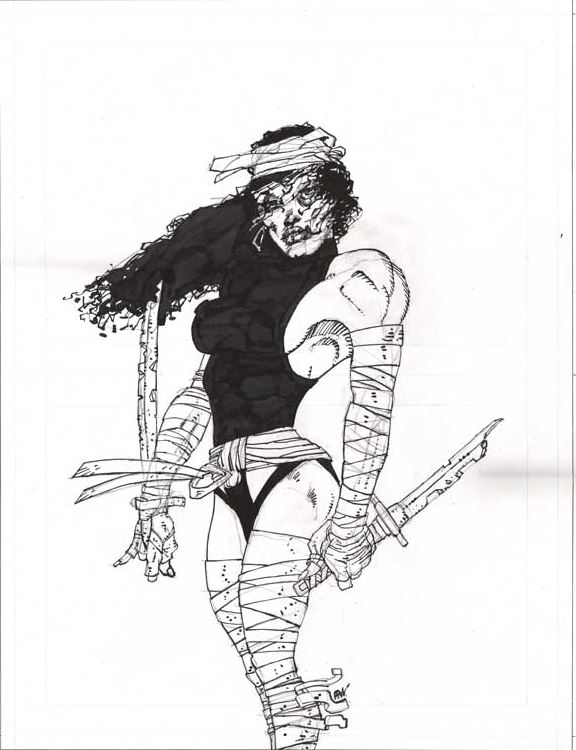

In that spirit, to propose how art can move beyond its (and our) own identity, i will offer an exegesis of the following panel from the comic-book The Dark Knight Returns by Miller,

Janson & Varley (DC Comics, 1986).

It is a Batman comic, with all the connotations about ‘secret identities’ that are apposite to our subject. Like most comic-book periodicals promoting the corporate-owned product of superhero characters, this book moves a fixed set of characters along a chessboard grid. That this particular version acquired a modicum of mainstream fame in its time, due to the introduction of certain radical elements into the Batman mythos, is of little significance.

Its central achievement is that it understands the medium; constrained by its nature as corporate product and juvenile entertainment, it finds freedom in the technical aspects of

storytelling, in the dance of the draughtsman’s hand.

A tale of an aged Batman coming out of retirement to fight crime one last time, it metes out, on the narrative level, heavy-handed symbolism and clunky metaphors in an attempt to instill the juvenile concept with a measure of adult validity. There is the Joker, whose face-paint reveals rather than masks his identity; Two-Face, one side of his visage horribly disfigured, mirroring the Batman’s dual nature, Superman portrayed as a spineless slave

to political power. The mask, the masked, nature and morality, with these themes and more, the book plays a pleasing aesthetic game, but for all its visual rhyme and striking juxtapositions, as a narrative it does not delve very deep.

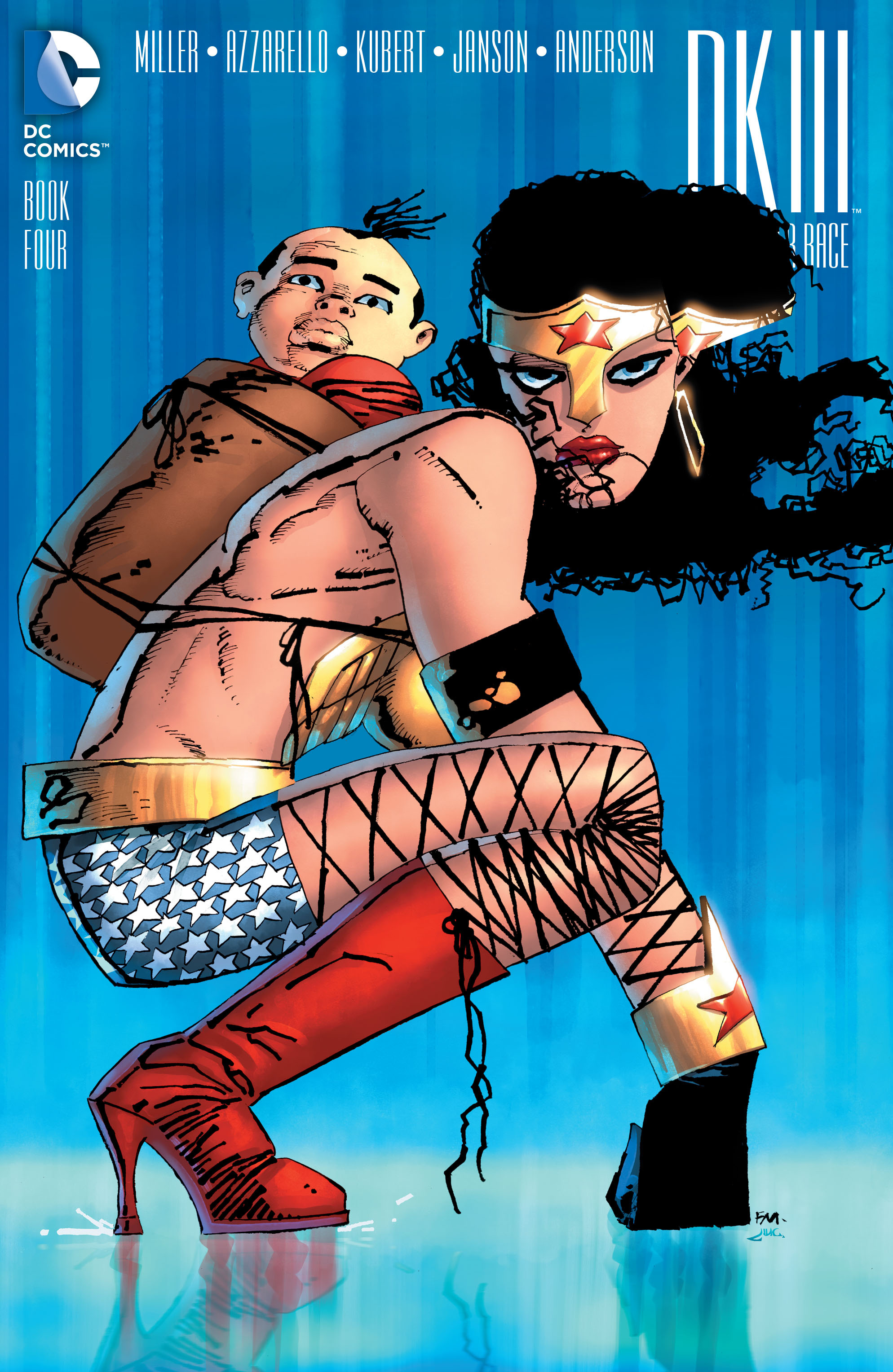

Yet despite this narrative superficiality, there are statements which only the comic-book image-maker is capable of making, and the comic-book storyteller through his technique must push the image-maker to the point where meaning (relevance to the plot’s progression, or symbolism pertinent to the story’s subject) becomes subsumed in the textures of the drawings – where the ink, as it were, is allowed to speak its own language; to comment, in blackness, on the proceedings in the narrative, creating a counter-narrative, the majestic current of a subterranean river traversing chthonic realms of obscure meaning.

There are statements which only the image-maker has the authority to make, and I hope to unearth some of these statements, and by this reversal of the artistic process, the extrication not just of meaning but of meaningfulness, the being-full-of-meaning, to show that the making of art is a ritual burial, a negation which leaves the disinterment , or resurrection, even, to the reader or spectator. It is a dying of the Self into the Other.

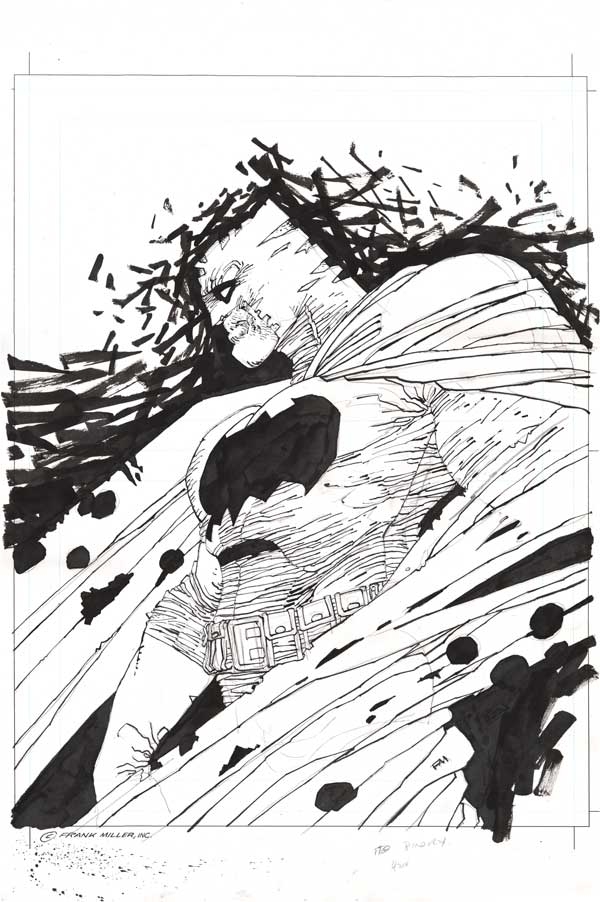

Taking as context the surrounding images, the panel reads as a face emerging over the rim of a circular mirror which has just confronted the face with the result of cosmetic surgery restoring its disfigured left side. But this reading does not take into account the key to interpretation we are offered when reading on. There, we find what is in every sense a key moment to the book; a flashback scene showing the pivotal moment that (however shallowly) motivated multimillionaire Bruce Wayne to ‘fight crime’ as the Batman: the death of his parents at the hands of a street robber. The flashback, designed as a rigid four-by-four panel grid imbuing the scene with the staccato inevitability of fate or nightmare, stretches and stretches until coming to a slow halt in the relentless close-up focus on the robber’s gun getting tangled in Mrs. Wayne’s pearl necklace, showing the gunshot against her neck only through the increasing distance between the pearls of the necklace as it tears; a constellation of white orbs against a black background, which becomes the blackness of outer space, unmooring the young Bruce Wayne from all notions of home and safety. Suddenly this boy is cast into a deep interplanetary coldness; his universe stretches like the necklace; the gaps widen as the pearls scatter, the planets fall; time stops; and the void yawns wide.

On the narrative level that scene is simply the key to the Batman’s pathology. On the visual level, we have been presented a manual instructing us how to read these images. Time has stopped; the pearls are no longer connected; it is Judgement Day, and each picture must stand on its own.

Thus, we come to the panel at hand, with all sense of human scale utterly blasted. An image of apocalyptic implications, with its opaque black globe encroaching upon a human face, leaving only one amazed, or frightened eye visible. A vast face peeking over the curving horizon of a blackened planet, like a sunrise witnessed from space.

And the word balloon says ‘oh, my god,’ -but who or what is it, that speaks?

The face has no mouth, no visible mouth at least, and the balloon’s tail points towards the black globe- black as the theatre of Lord Chamberlain’s men ( Shakespeare’s troupe),The Globe, after it had been reduced to ashes by fire- a blackened Globe, a full stop, an end to masks and costumes and assumed identities.

The blackness, unmasked, speaks. Let us pause to examine how this blackness manifests itself in a few other instances, to help give direction to our reading.

Batman’s costume is traditionally depicted as having a blue colour, we can assume to suggest night or darkness while still keeping the figure legible when drawn against a night sky or in darkness. But throughout The Dark Knight Returns, the night sky is painted in subtle hues of dark metallic blues and greys, with Batman outlined starkly against its gradients in pure black silhouette. Like the familiar trick of the picture that represents at once two faces and a vase, foreground and background here shift their significance between them:the sky becomes illustration, painted backdrop behind the iconic shape of Batman’s absolute blackness, but it might also be perceived that the perfect night sky has been pierced, revealing a more profound darkness behind it. An image not to look at, but through.

Let us return with this idea, the suggestion that there is a darkness underlying all surfaces,to our original picture, and examine it anew.

It is, of course, a hole. A hole in a picture of a face. Or rather, it is the face of nothingness of that face, the individuality punctured, and it is this face of nothingness which exclaims, with the last vestiges of personality: ‘oh, my god.’

As Shaykh Lahiji writes in his commentary on Mahmud Shabestari´s Golshan-e Raz (the Rose Garden of Mystery): “Suddenly i saw that the black light was invading the entire universe. Heaven and earth and everything that was there had wholly become black light and, behold, I was totally absorbed in this light, losing consciousness.”

This black light (nur aswad), which in some traditions is seen as the hair of God invisibly permeating the universe (predating by several centuries the concept of Anti-matter of contemporary physics) is not to be mistaken for mere darkness, a simple absence of light.

It is very precisely not a matter of negativity, of emptiness or absence. In fact, in the light of what we have previously established, it is the Ink that speaks, that articulates the blackness. And this Ink, because it holds the promise of all forms, as writing, or drawing, can be said to represent an incomparable plenitude.

There are two curious and little known sayings of the prophet Muhammad: “All that is in the revealed books is in the Qur’an and all that is in the Qur’an is in the Fatihah [the Qur’an’s opening verse], and all that is in the Fatihah is in Bismi’ Llahi ‘r Rahmani ‘r-Rahim [the Fatihah’s opening line or Basmalah].” and “All that is in Bismi’ Llahi ‘r Rahmani ‘r-Rahim is in the letter Ba, which itself is contained in the point that is beneath it.”

Shayhk Ahmad Al-‘Alawi, who lived in Algeria at the beginning of the previous century, wrote a treatise on this subject, titled ‘The Book of The Uniqe Archetype which signalleth the way unto the full realization of Oneness in considering what is meant by the envelopment of the Heavenly Scriptures in the point of the Basmalah,’ and therein, to illustrate his point (and The Point), he quotes at length Abd al-Ghani an-Nabulusi, from the Diwan al Haqa’iq, about Ink:

“For it was before the letters, when no letter was;

And it remaineth, when no letter at all shall be.

Look well at each letter:thou seest it hath already perished

But for the face of the ink, that is, for the Face of His Essence,

Unto Whom All Glory and Majesty and Exaltation!”

It is a commonplace of the comic-book craft that a picture must not describe what the text is saying and vice-versa, but the obverse of that coin is that a text which means the same as the picture but describes it in a different way is a felicitous convergence and divergence at once; the two aspects of the medium maximizing each other’s potential.

Of our picture and text- our picture as text-both instances are true. Without exclamation mark, the phrase by itself is a quiet expression of baffled incredulity, a sigh perhaps, although its subtlety is undermined by the italicized emphasis of “god,” while the open-endedness of the sentence as indicated by the three dots articulates a bridge to the surrounding image.

But the words, too,form a picture, the ‘oh’ being both the sound and the form of the silent black void encroaching upon the face.”O” is the circumference of the Basmalah’s Point; the outward manifestation of the all-encompassing blackness of the Ink representing the Incomparable Plenitude of the Divine. The “O” therefore signifies the same as the italicized “god.”

The third word in the balloon(“My”) is there to act as a bridge between these two manifestations of the Divine, if only it can allow itself to surrender to the engulfing Black Light spreading over its image. Like a mirror, it is the conduit through which the Divine passes on Its way to Itself. In Its path, It completely obliterates “my” and “I” and all notions of Selfhood, for once the Self has seen the True Reality of its Absorption into the totality of the Ink, it ceases to be anything other than the Ink; It can only recognize, from then on, the Ink-ness as it were, of its existence. As the “my” falls away from the text, and the face is obliterated in the picture, God as text and God as meaning cross the divide of Selfhood to become the One which the illusion of “my” tried to oppose. Identity perishes. Blackness surrenders to the meaning of blackness. And that is the Face which ever remains.