Yesterday, Osvaldo Oyala posted an essay about the DC character Black Lightning, focusing particularly on how the characters’ two series (written by Tony Isabella) failed to address issues of race. Along these lines, Osvaldo wondered how race was handled when Black Lightning appeared in the team book, Batman and the Outsiders, during the 1980s.

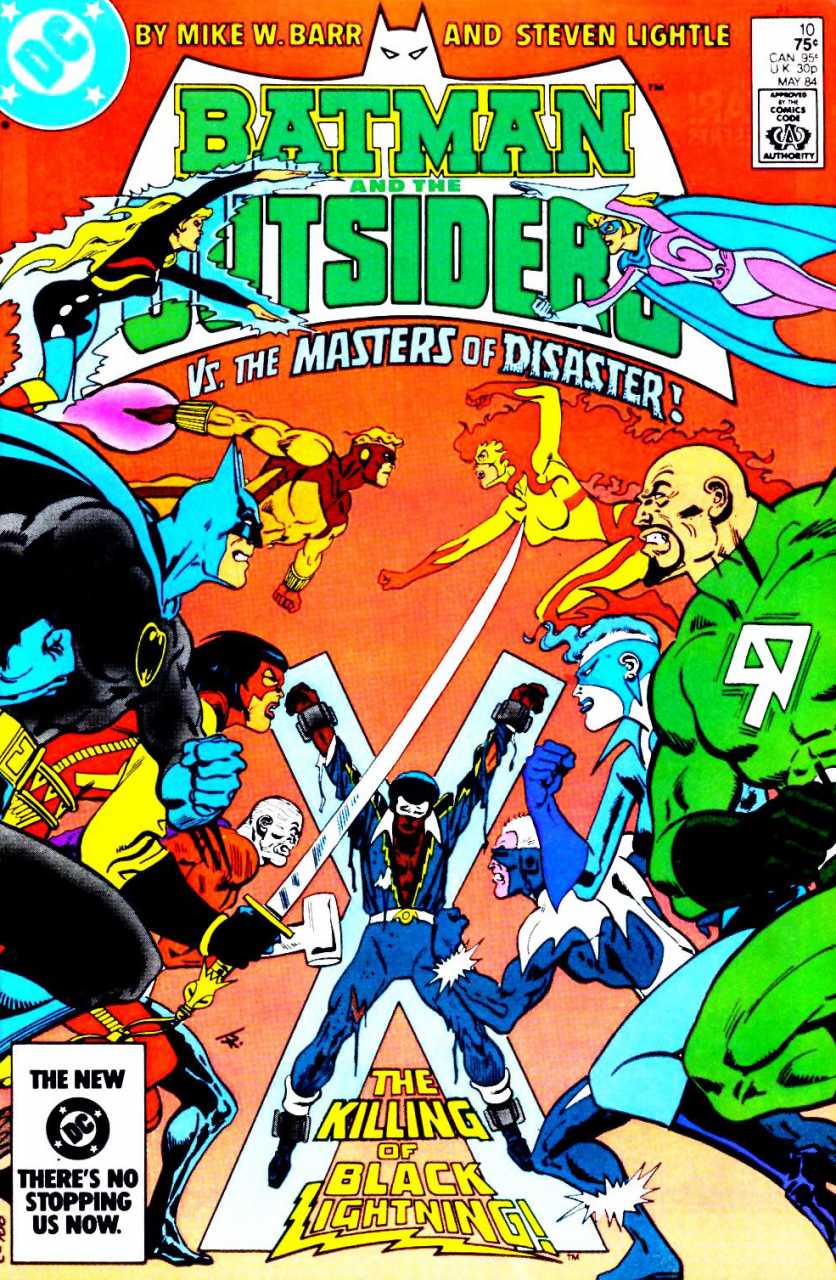

I read those comics when they came out, and my memory was that race was barely mentioned, much less dealt with. I thought I’d double-check, though, and so I went ahead and reread Batman and the Outsiders #10, by Mike W. Barr and Steven Lightle titled…The Execution of Black Lightning!

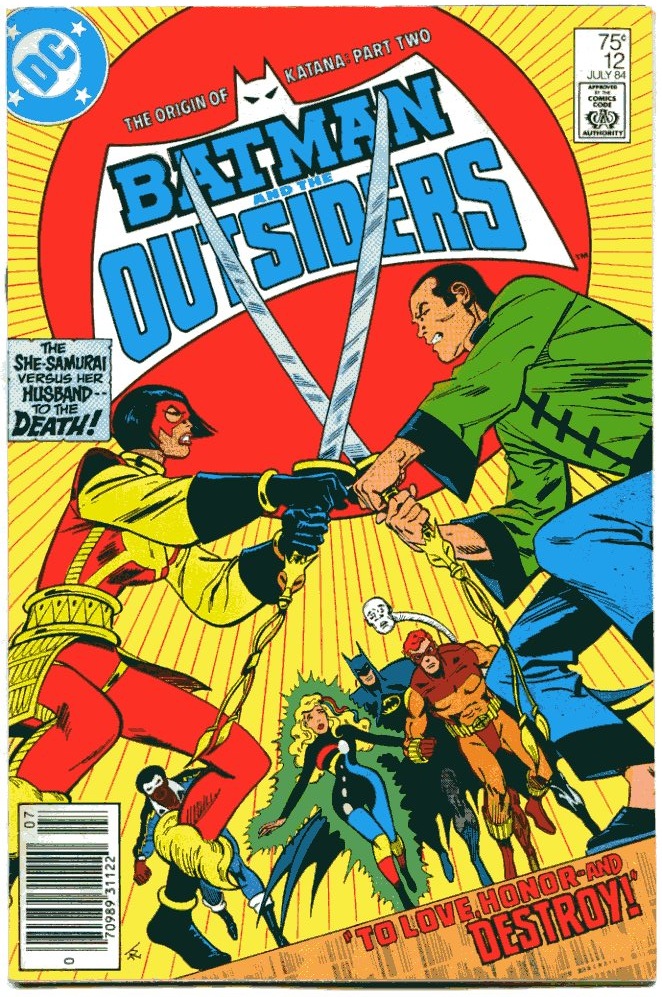

There’s black lightning, dead center, manacled to a structure which evokes a cross, clothes torn. It’s hard to avoid the evocation of slavery, and the link between African-American suffering and Christ. And yet, all those other characters on the cover do manage, somehow, to avoid it; the charged history of blackness in America hangs there suspended, while various costumed clowns square off for their tiresome Manichean good white guys vs. bad white guys battle, burying trauma under the high-pitched shuffle of silly costumes.

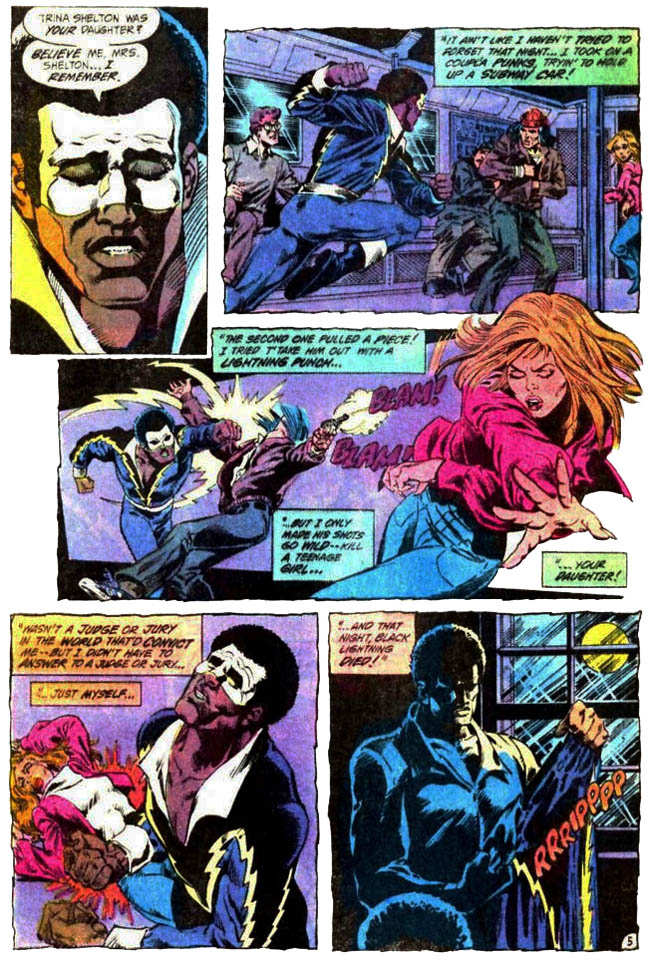

That’s fairly typical of how the comic as a whole works. Black Lightning’s blackness functions as an almost but not conscious theme, instantly and insistently deferred and repressed. The plot of the comic (such as it is) involves Lightning’s own traumatic tragic backstory — while he was fighting soem robbers on a subway car, a bullet went astray and killed a teenage girl named Trina nearby. Lightning blamed himself, and the trauma caused him to have trouble with his lightning powers, and to quite superheroing, until Batman convinced him to join the Outsiders (and helped him recover his lightning abilities). Trina’s mom, though, remained embittered, and so (as you will) she hired a team of supervillains to kill BL.

Again, race here flutters about, shooed away before it can quite settle. This was the 1980s, before the crack epidemic, but still, I think death by stray gunshot would be legible as a problem that particularly plagued gang-ridden minority communities. You have a black superhero, then, dealing with a violence and a trauma that is particularly associated with black communities.

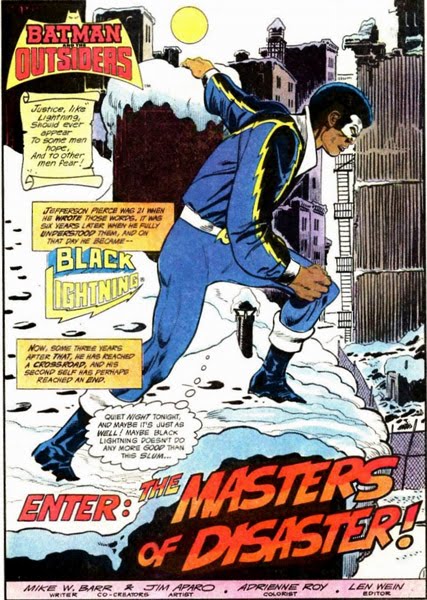

And yet, the racial, and for that matter the class, connotations of the storyline are insistently disavowed. The girl killed by the thugs is white; her parents are presented as thoroughly middle class (with enough money to hire assassins, even.) Although BL was, as Osvaldo notes, originally presented as a hero particularly committed to inner-city and poor neighborhoods, he never appears to connect his particular, individual trauma to the trauma of those communities. Or, when he does, as in a couple page sequence in the previous issue, it seems designed specifically to replace the community with some guy in tights who can be taken out of them.

“Maybe Black Lightning doesn’t do any more good than this slum.” And that’s as much of a meditation as we get on race; inner-cities as throwaway metaphor for Black Lightning’s inner angst.

Similarly, the plot arc — a black man accused by middle-class white folks, chained and (almost) executed without trial — has pretty obvious parallels with African-American historical experiences of lynching. But neither creators nor characters seem to notice. The iconography (as on the cover) just sits there, as if daring the reader to make a connection. Black Lightning functions here not to present black characters or black experiences, but to studiously deny both. History and iconography are accessed simply to be denied; it’s an object lesson in how tokenism can be used not to grant visibility, but to more completely erase. The comic is almost a dare; how much African-American history can we pretend has nothing to do with African-Americans? The answer being, essentially, all of it.

In that sense the bulk of the Outsiders comics that don’t focus on BL are actually something of a relief. For the most part, he’s just another one in the crowd of superfolk, disinguishable by his costume and powers but not by anything else. In the black and white reprint volume I’ve got, even his skin color doesn’t set him apart. There’s only that Afro and the occasional more or less random lurch into dialect to remind you that the race-blindness here isn’t egalitarian, but simple, determined ignorance. They may claim they’re saving him, but none of those heroes on the cover is willing to look over at the black guy on the cross.