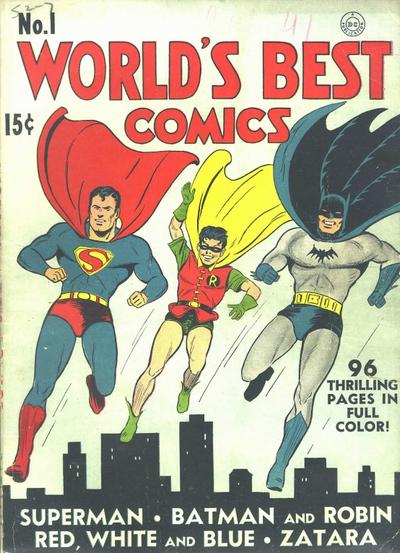

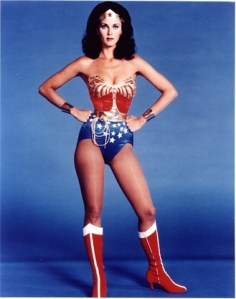

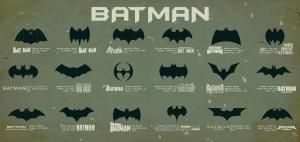

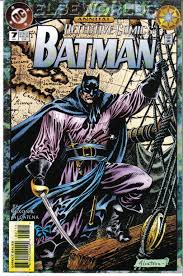

The return of Arrow and The Flash from their midseason break continues the love-fest each program has enjoyed with fans. The CW’s dynamic duo (sorry) has sparked hopes of a DC cinematic universe by bridging the gap between diehard fans and casual viewers. Nothing illustrates this point more than this season’s semi-crossover event. Skillfully executed and action packed, each character visited the other’s show. Oliver Queen’s darker persona coming into contact with the “brighter” world inhabited by Barry Allen (and vice versa) reminded fans of World Best Comics #1 (Later World Finest Comics) that featured Batman and Superman in 1941. This comic hinted that Batman and Superman lived in the same world. Ironically, it was only the covers that placed the heroes together; they did not actually appear in the same story until 1952. Embellishing episodes that are already deeply informed by decades of stories and developed and produced by the same creative team, Arrow and The Flash deliver a better experience.

World Best Comics Vol. 1 #1 (March 1941)

The shared universe idea that developed from the 1940s onward grew more complex drawing in fans and accommodating new characters and worlds. Creators hope this legacy means fan engagement with these cinematic adaptations will impact engagement on other platforms. Yet, as recent research about the transmedia idea explains whatever the technological tools and industrial alignments shaping storytelling, these products cannot escape the sociocultural context informing the audience experience.[1] While Arrow and The Flash are satisfying action adventure serials, this season’s crossover also highlight the historical burden linked to the superhero genre.

DC Comics characters inform the popular imagination about the superhero. For years adaptations of DC characters have served as vehicles for generational discourses. Batman’s 1960s television series and Superman’s 1970s film highlight this tradition. The Batman television series leveraged the Pop Art Movement to create an “exaggerated cliché” that delighted children and amused adults.[2] At the same moment, Roy Lichtenstein blurred the boundary between high culture and commercialism using comic book panels in his images.[3] Derided at the time, his work, like TV series, resonated with the public reflecting societal tension with the postwar conformist message in America. By the time Richard Donner’s Superman graced the silver screen in 1978 the United States had been disabused of its global preeminence by failures abroad and domestic politics splintered by protests from the left and the right. Americans were uncertain and as Jimmy Carter famously explained, a crisis of confidence casted a “…growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives” and the “unity of purpose for our nation.”[4] Donner’s Superman offered an affirmation of American ideas. Not surprisingly, Carter lost his re-election campaign and adjusted for inflation Superman remains the highest gross adaptation of the Man of Steel on film.[5]

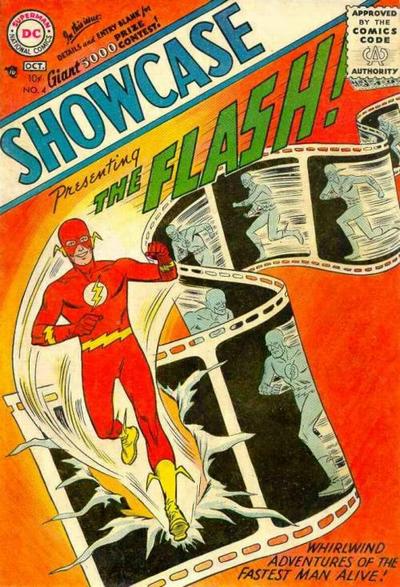

Showcase Vol 1. #4

The circumstances that shaped the pro-social mission in the original Superman and Batman reflected depression struggles and wartime triumphs. In a similar manner, the superhero comic book revival associated with Barry Allen’s debut as The Flash reflected the postwar experience. Created by Robert Kanigher, John Broome, and Carmine Infantino in 1956, Allen was the second Flash and sparked a superhero renaissance that re-imagined 1940s characters for the atomic age. Allen’s earnest commitment to family and community along with his civilian identity as a “police scientist” affirmed the moral standard established by The Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA). The CMAA’s regulatory arm, the Comic Code Authority worked to eliminate corrupting images and ideas critics linked to comic books. Famously articulated by Dr. Fredric Wertham, comic books became seen as central cause of juvenile delinquency in the early 1950s. The resulting hysteria led to Congressional hearings investigating comic publishers in 1954.[6] Recent work by Amy Kiste Nyberg does an excellent job of demonstrating how Wertham was as much a symptom as a cause of Americans’ suspicions. The confluence of Cold War tension, postwar affluence, and youth culture provided ample opportunities for parents to worry and children to rebel. Those kids endangered by comics would embrace the disruptive rhythm of rock ‘n’ roll music and go off to college and protest…everything.

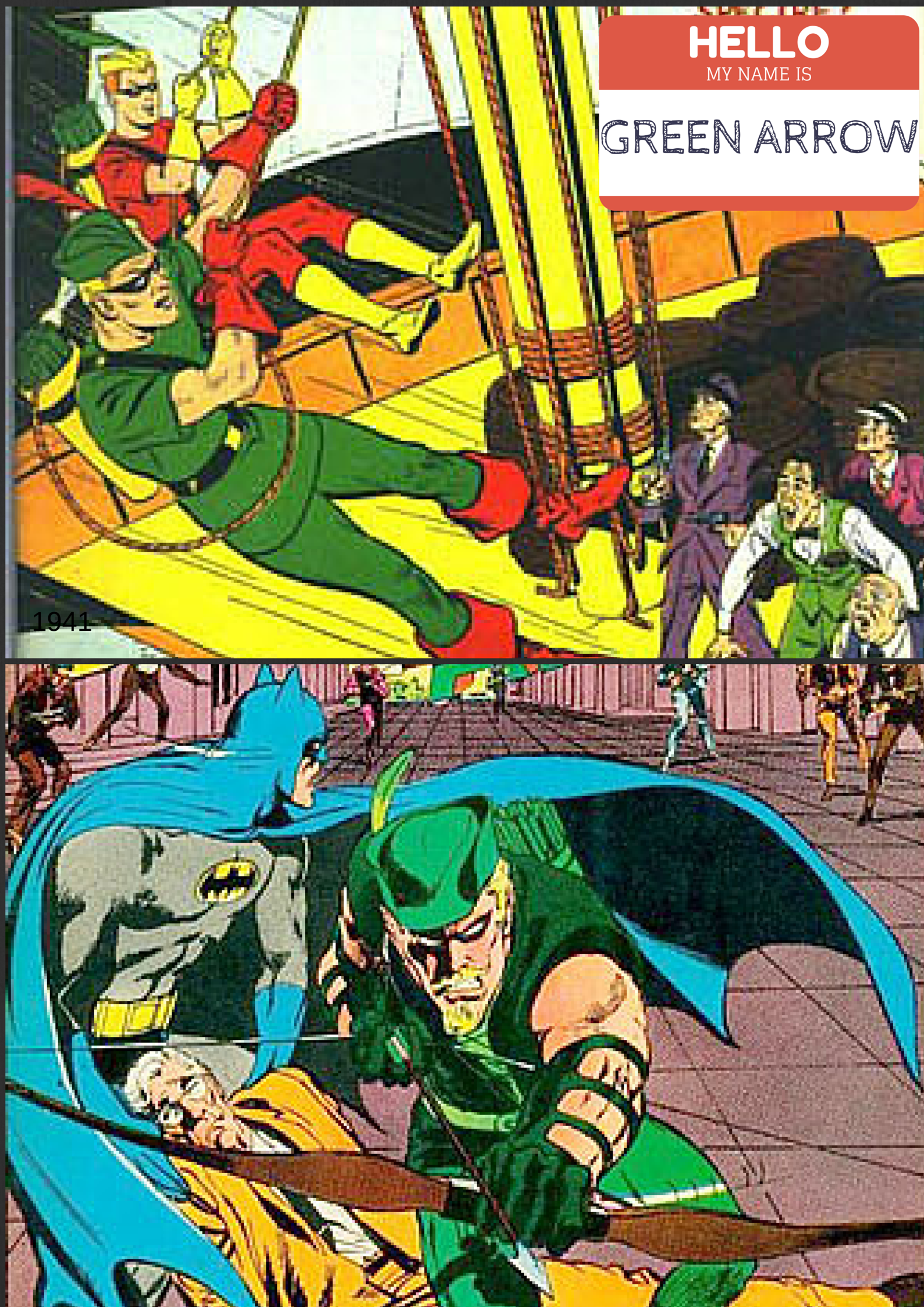

As comic book publishers strove to keep this dynamic youth engaged, they continued to revamp their characters to reflect changing time. Green Arrow, created in 1941, was more “Batman-lite” than an iconic character until Neal Adams and Dennis “Denny” O’Neil re-designed him in 1969. Oliver Queen had been a rich man with a teenage sidekick who employed trick arrows and worked from secret headquarters called the Arrow Cave (with an Arrow Car of course). The “new” Green Arrow lost his fortune, discovered his ward was a drug addict, and in the classic series paired with Green Lantern travelled the country in the early 1970s confronting crimes rooted in “real world” concerns like racism and environmental damage.[7] The link to ‘relevance’ in superhero comics has never left Green Arrow, but arguably his frustration with authority has shifted in recent years from the ardent liberalism of the 1960s to a disillusioned libertarianism today.

In Arrow and The Flash this history informs the narrative world we see on the screen and shapes the shared universe they inhabit. Allen’s Flash and Queen’s Arrow approach their mission differently, a point made clear when each hero applies their methods in the other’s city. Allen retains the expectations and aspiration associated with postwar America, but slightly modernized. Despite the tragic circumstances he has faced, he is committed to making his world better. Arrow has taken Green Arrow’s social justice narrative and re-oriented it with a criminal justice lens. Like the country as a whole, his grievance with “the system” has grown at once more and less complex. He struggles with morally questionable actions in his past as he pursues a heroic future. Informed by contemporary culture, both adaptations are a prism on values inscribed in each character. As Arrow and The Flash continue to create a richer world, the evolution of their narrative legacy provides a roadmap of how the contemporary audience’s concerns about security and community contend with changing millennial realities. The popularity of the shows makes sense as a catharsis exercise. That the superheroes will triumph is not the question. Instead, how they win and remain heroic becomes the key. Queen’s Arrow doesn’t want to be a killer that relies on torture to protect those things he loves and Allen’s Flash doesn’t want to be so afraid he is unable to act. For all the fantastic excesses linked to superheroes, the broader questions they are in dialogue with matter to us all.

______________________

[1] Carlos Scolari, Paolo Bertetti, and Matthew Freeman, Transmedia Archaeology: Storytelling in the Borderlines of Science Fiction, Comics and Pulp Magazines (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), viii–viii, http://www.palgrave.com/page/detail/transmedia-archaeology-carlos-scolari.

[2] Judy Stone, “Caped Crusader of Camp,” New York Times, January 9, 1966.

[3] Peter Sanderson, “Spiegelman Goes to College,” PublishersWeekly.com, April 23, 2007, http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/1-legacy/24-comic-book-reviews/article/14675-spiegelman-goes-to-college.html.

[4] “WGBH American Experience. Jimmy Carter | PBS,” American Experience, accessed December 26, 2014, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/carter-crisis/.

[5] “Superman Moviesat the Box Office – Box Office Mojo,” accessed December 26, 2014, http://boxofficemojo.com/franchises/chart/?id=superman.htm.

[6] “1954 Senate Subcommittee Hearings into Juvenile Delinquency (Comic Books),” accessed October 26, 2013, http://www.thecomicbooks.com/1954senatetranscripts.html.

[7] Jesse T. Moore, “The Education of Green Lantern: Culture and Ideology,” The Journal of American Culture 26, no. 2 (2003): 263–78.