This first ran on Salon…and then Salon deleted it. Not sure why; I suspect a glitch. I tried to notify the editors, but they didn’t do anything…so what the hey, I figured I’d reprint it here, since they don’t seem to want it.

___________

Lately critics have piled on the chick flick “The Other Woman” for one specific reason: it doesn’t pass the Bechdel test— Alison Bechdel’s famous heuristic which asks whether a film has (a) two women who (b) talk to each other about (c) something other than a man. As Linda Holmes says in a particularly scathing review at NPR, “ “The Other Woman” is 109 minutes long, and at no time do any of these women—including Carly (Cameron Diaz) and her secretary (Nicki Minaj), who only know each other from work — pause for a discussion, even for a moment, of anything other than a series of dudes…” Vulture put a clever new spin on this argument by collecting all the lines Kate Upton says in the movie, which included: “I can’t believe he’d lie to me, I really thought we were soul mates” and “We could kick him in the balls!”

Having a film featuring three female protagonists who do nothing but talk about men is, the Bechdel Test suggests, unfeminist. Let it be known, though, that “The Other Woman” does technically pass the Bechdel Test: Kate (Leslie Mann) has a very brief conversation with Amber (Kate Upton) about how good Amber smells. Still, the films female friendships are all based on the women’s relationship with a single, caddish guy. Those applying the Bechdel Test say that this is a failure. But if a movie for women, with female stars, about female friendships and the evils of male infidelity can’t pass the test, maybe the problem isn’t with the film, but with Bechdel’s rubric.

The truth is that female genre fiction (whether movies or TV or books)— designed for and consumed mostly by women—not infrequently has difficulty passing the Bechdel Test, precisely because female genre fiction is often really interested in men. The Twilight films don’t do well. Neither do many romance novels, as romance novelists like Jillian Burns and Jenny Trout have acknowledged.

Tessa Dare’s 2012 Regency romance “A Week to Be Wicked,” for example, features as its heroine Minerva, a determined geologist who becomes a noted scientist in the teeth of contemporary mores while also showing an unexpected flair for passion and screwball comedy. There’s no doubt that the book is self-consciously feminist — the scientific community’s exclusion of female scientists is a major plot point, and one of the things that Minerva loves about the hero, Colin, is that he isn’t threatened by her accomplishments. But despite such support for female empowerment, “A Week to Be Wicked” doesn’t really pass the Bechdel Test. When Minerva talks to her beloved sister or to her mother, it’s about Colin. There are a few ensemble scenes in which Colin and Minerva fool a carriage full of women into thinking that they’re royalty on their way to a kingdom on the border of Spain and Italy — so that might technically count, if you were determined to make it. There’s probably another moment or two as well; books find the tests easier to pass just because they’re longer than films. But as with “The Other Woman” — or really even more than with “The Other Woman” — the story in “A Week To Be Wicked” is about the relationship between the female lead and the male lead. And that means that the female lead is generally either talking to the guy or talking about him. There’s not a ton of space for extraneous Bechdel-appeasing conversations.

A genre novel that fails the test even more spectacularly is Alex Beecroft’s “False Colors.” There are hardly any women in Beecroft’s romance novel at all. It’s M/M — a gay historical novel set mostly aboard ship with the British Navy. Despite the failure to pass the test, M/M novels in general are hardly anti-female. Beecroft is a woman, her readership (as with most M/M) is probably predominantly women, and the female characters we do see are treated with sympathy and surprising depth given how little screen-time they get. I particularly liked the fortiesh widow, Lavinia Deane, who flirts with one of the heroes and figures out (with no bitterness) why he won’t flirt back before he fully understands it himself (“Say you won’t try to be some sort of saint in the wilderness,” she says with earthy kindness, channeling the wishes of both author and readers. “I’d hate to think of you withering away untasted.”)

But such bright cameos can’t change the fact that, as far as the Bechdel Test goes, the novel fails big-time. I don’t think there’s a scene in which two women talk to each other, much less talk to each other about something other than men. As M/M writer Becky Black says about her own books and the Bechdel Test, “I personally usually structure the story so every scene will be from the Point of View of one or the other of the heroes. All of this means there isn’t much space for the female characters to have a chance!”

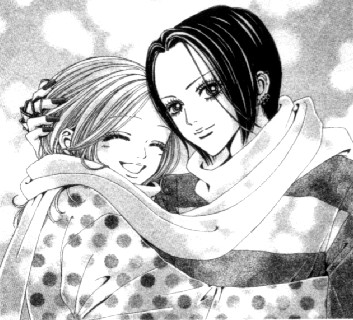

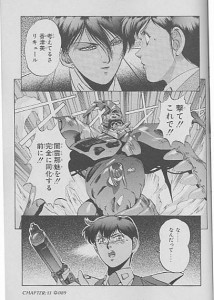

M/M romance, and associated genres like yaoi manga and slash fiction underline the limits of the Bechdel Test. It’s true that a book like “False Colors” doesn’t have many female characters — but that’s because the author fully expects the audience to identify, and fantasize, across genders. In “False Colors,” both leads play the role of damsel in distress, and both play the role of heroic rescuer. The Bechdel Test assumes that men are men and women are women. But questioning that assumption can be a feminist project in itself.

The point here is simply that — as many of the romance authors I’ve linked say — the Bechdel Test has some limits. Alison Bechdel has said she doesn’t use it as a “filter” for herself , as her character Mo did. The test can be a useful way to think about how gender works in films or books, but alone it can’t tell you whether something is good or bad, or feminist or unfeminist.

It’s also, though, worth thinking about the way that the Bechdel Test fits a bit too neatly into cultural and feminist prejudices against genre fiction. Mo is a lesbian, so it makes some sense that she wouldn’t be interested in the kind of stories where women are focused on heterosexual romance (even though there certainly are lesbians who enjoy het romance.) But should that really be turned into a general rule suggesting that women’s interest in heterosexual relationships is somehow unfeminist, or a sign of aesthetic failure?

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s sneer at “that damned mob of scribbling women” to Lisa Jervis’ assertion that chick lit is responsible for the “evacuation of feminist politics,” men and certain strands of feminism have long been united in seeing female genre fictions as weak, foolish, corrupt, and even corrupting. Using the Bechdel Test as a way to chastise women for enjoying the wrong, insufficiently highbrow, unfeminist thing — whether that be The Other Woman, or “Twilight,” or romance novels — seems like it fits into that unfortunate tradition of gendered scorn. The Bechdel Test remains a useful lens for looking at art. But it’s important to remember that Bechdel’s Rule is, itself, a cultural and aesthetic product. If Bechdel’s comic can be used to test romance, or chick flicks, then romance, or chick flicks, can be used to test Bechdel as well.