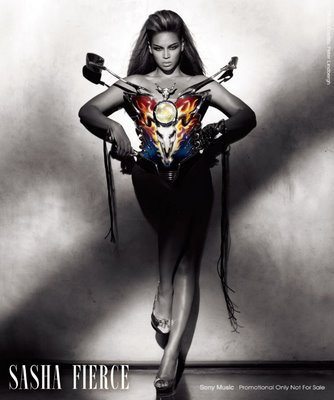

“I just might be a black Bill Gates in the making,” Beyoncé declares in her new video “Formation.” It’s an unapologetic, swaggering declaration that she is a businesswoman and a power to be reckoned with. That’s not an unusual boast for the singer—her 2013 video for “Partition” opens with her languidly ordering about a (notably white) servant. But it does clash a little with “Hymn to the Weekend“, the video she released only a few weeks before in collaboration with Coldplay.

As I discussed last week, “Hymn to the Weekend” is set up as an Orientalist tourist video. Coldplay singer Chris Martin drives around in a cab, staring out at Mumbai, and relishing exotic displays of street art and the high spirits of street kids. India is figured as exotic and exciting. But it’s also presented as poor, earthy, real, visceral. For the video, the people of India are fun to stare at because they are not Bill Gates, and because they are outside the logic of the capitalist west. Here, the video proclaims, as Martin moans on about feeling drunk and high, is an ecstasy that isn’t about money and fame. It’s an experience you cannot purchase, even with your tourist dollars. It must be lived.

Though Beyoncé is dressed up as a glamorous Bollywood singer, she doesn’t change that narrative. She’s certainly opulent—but that’s figured as a mystic, distant opulence, set against spiritual landscapes, not as a wealth obtained through sweat and smarts. She exploits Orientalist tropes to make herself exotic and exicting, but those tropes end up defining and limiting her. In joining with Coldplay to make herself a Orientalist mystical totem, she gives up her role as entrepreneur.

She takes it back in “Formation,” though. In her own video, Beyoncé isn’t stuck in any one role. Instead, the video, set in New Orleans, puts her in a range of identities, from upscale buttoned up gentlewoman to street-level twerker, from historical to present-day. “Through this reckless country blackness, she becomes every black southern woman possible for her to reasonably inhabit, moving through time, class, and space,” Zandria Felice Robinson writes. Beyoncé is both marginal and empowered, both looker and spectacle.

It’s important that that the culture that inspires the video is treated with much more respect than in the Coldplay collaboration, in no small part because the community in question is one that Beyoncé identifies with. This isn’t just a matter of presenting herself as part of Southern black culture; it’s also about knowledge and respect. “Hymn to the Weekend” could have gotten a Bollywood star to appear alongside Beyoncé, but no one cared enough to bother making that happen. As a result, the video feels like something done to, rather than in collaboration with, Mumbai and its culture. In contrast, “Formation” includes New Orleans bounce performers Messy Mya and Big Freedia. It honors queer dancers and rappers whose style has been much imitated in the mainstream, but whose personal artistry is rarely acknowledged there.

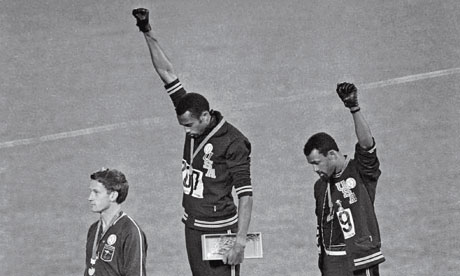

“Formation” also differs from “Hymn to the Weekend” in that it presents marginalization not as exotic spectacle, but as struggle. The most instantaneously famous images from the video are of a black child dancing in front of an ominous line of police, and of Beyoncé lying on a sinking patrol car as the video’s close. The New Orleans presented in the video is not a tourist destination. It’s a city under siege, both by neglect in the wake of Katrina, and by state violence. There is joy there, but there’s also an insistence that the joy is not meant to be comfortably viewed from a cab. It’s an act of defiance.

And part of that defiance is the video’s deliberate, amused consumerism. “I’m so reckless when I rock my Givenchy dress/I’m so possessive so I rock his rock necklaces.” Beyoncé is Bill Gates; she wants, or already has, power, wealth, glamour, respect, and brains. She’s a businesswoman, which means she’s the entrepreneur making the video, not just the person the video is about.

Beyoncé’s been criticized at times for embracing capitalism and the iconography of wealth. But the “Hymn to the Weekend” video is a reminder that capitalism isn’t just about money. It’s about inequities of power, about who is owned, and about who gets to be the one who does the owning. The children Coldplay watches in Mumbai don’t get to say, with Beyoncé in “Formation”, “I’m so possessive,” because they aren’t seen as having their own desires. They are treated as the things to be consumed, not the consumers.

“Earned all this money, but they never take the country out me,” Beyoncé declares. Through double consciousness, she can be Bill Gates and herself at the same time. Poverty isn’t natural or fun. The people who don’t have power, want power, and are justified in wanting it. To tell them they should be different in kind from the capitalists is just what capitalism, and capitalism’s police force, always tells them. Beyoncé, at least in “Formation,” isn’t buying it.