Bill Waterson’s Calvin and Hobbes is a strip about the wonders of imagination. And, as this famous Sunday shows, the wonder there, and the imagination as well, is insistently self-referential. The opening white space of the page is a nod to the white space of the page, so that the page represents the moment before creation just as the moment before creation turns around and represents the page. The calligraphy foregrounds the artist’s hand, even in the usually ignored realm of lettering, while the close-up of the eye-of-Calvin winks at Watterson’s own eye, gazing down upon the page. Calvin’s virtuoso acts of creation, the planets he sets spinning, are, at the same time, Watterson’s virtuoso acts of creation. That hand, from which a galaxy forms, points to Watterson’s actual hand, from which the galaxy forms. “He’s creating whole worlds over there!” Calvin’s dad enthuses, by which he means Calvin, but which could also, and does also apply to Waterson himself. The mom’s response, “I’ll bet he grows up to be an architect,” is ironic because Calvin’s imagined creation/destruction of the universe is figured as gleefully asocial rather than as a career path. But it’s also ironic simply because she’s got the wrong profession. Calvin is training to be an artist/cartoonist, not an architect; his future is, literally and figuratively, Watterson’s present. The comic can be read not as a winking laugh at the distance between child/adult perceptions, but as a kind of smug moment of gloating; Watterson/Calvin is cooler than his parents and cooler than architects. He’s a gloating god who gets paid not just for the creation, but for the gloating.

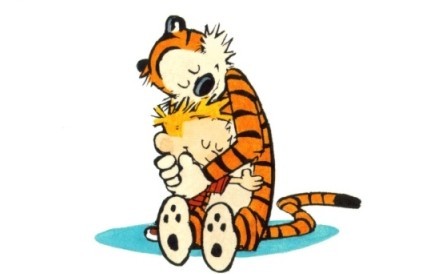

The strip’s celebration of imagination is predicated on the link between Calvin and Watterson. But that link is itself created through careful separations; to make Calvin and the cartoonist parallel, certain lines can’t meet. Thus, here, as throughout Calvin & Hobbes, the barrier between imagination and reality is carefully maintained. Calvin’s imagination is rendered in a more detailed, more expressionist style, again, even the text is written in calligraphy; reality, on the other hand, is drawn in Watterson’s standard cartoony format. The child’s-eye world and the parent’s eye world are visually and conceptually distinct. The wonder of Calvin’s imagination, and of Watterson’s, is figured specifically as a wonder by making clear that it is set off from the normal and everyday. Hobbes the tiger is a marvelous creation because the purity of the creation is underlined by Hobbes the stuffed animal. In order to celebrate childhood and (Calvin or Watterson’s) creativity, you need a nothing, a blank, to stick it in and compare it to.

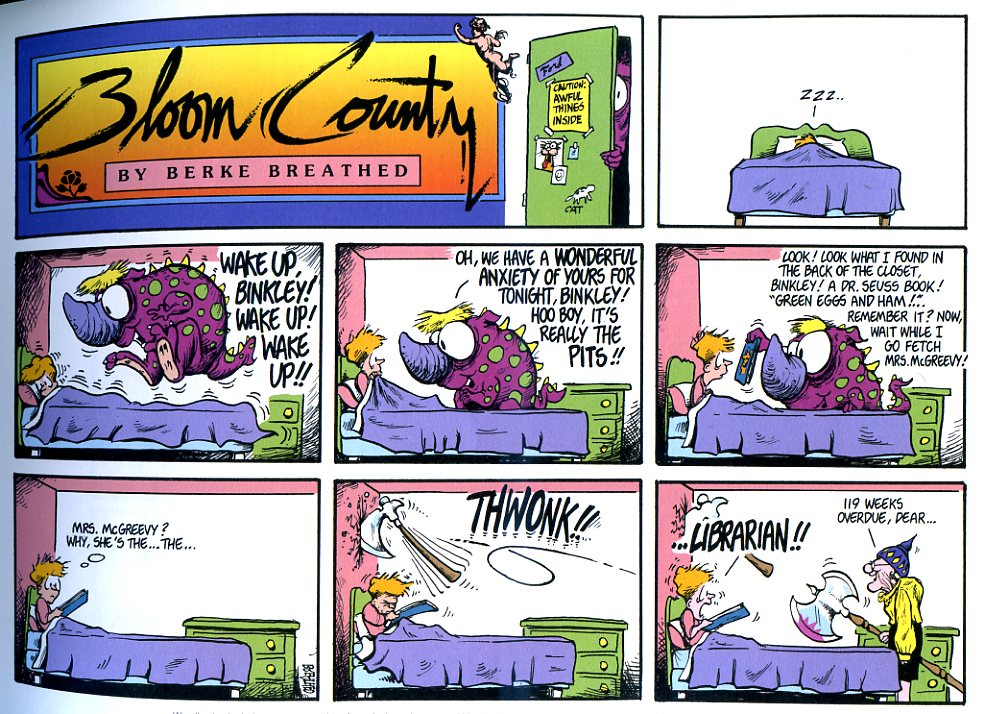

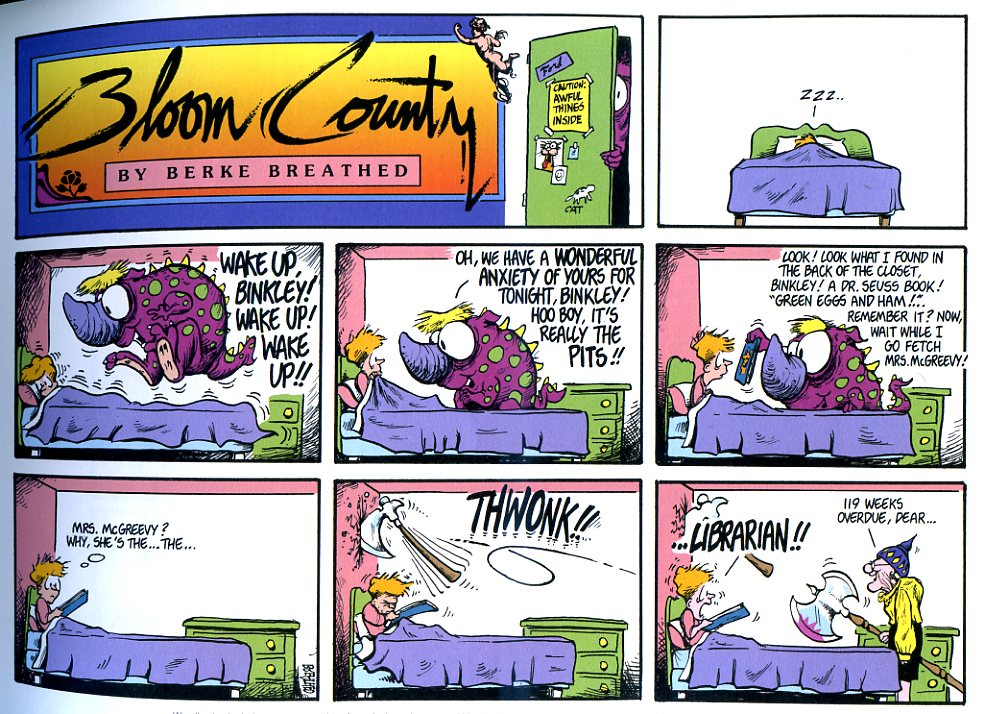

Bloom County’s treatment of imagination and of childhood works quite differently. This strip, for example, does not start with blank space, to be filled with creativity. Rather, it starts with Binkley being woken up by a Giant Purple Snorklewacker — you come out of dream to be in a dream. The one panel with no fantastic elements is not at the end — as ironic reassertion of the real — but in the middle, as a kind of pause or beat between absurdities. Nor is there a stylistic indication of what’s real and what isn’t. The Snorklewacker’s shock of unruly hair looks much like Binkley’s shock of unruly hair; Mrs. McGreevy looks like any other pleasantly dumpy Breathed old person except for that ax.

The imaginative content here is also less virtuoso riff than fuddy-duddy pratfall. In fact, the narrative seems designed to conflate the joy of childhood with the banal worries/fantasies of adults, so that “Green Eggs and Ham” becomes an occasion not for gleeful rhyming, but for worrying about due dates.

Nor is it just childhood fantasies that are punctured; in his notes to this cartoon in the Bloom County library reissue, Breathed notes that the strip was inspired by discovering his own out-of-date library book — a Frazetta art book. Mrs. McGreevy in Viking helmet can be seen, then, as a parody of Frazetta’s barbarians, and also as a kind of back-handed (back-axed?) comment on Breathed’s own imagination, or lack thereof. Give me a noble warrior, Breathed says, and I will turn it into a librarian and a neurosis. Breathed may be the Snorklewacker, gleefully leaping up and down in anticipation of tormenting his character, but he’s also that character, Binkley, who worries the way adults worry. The line between adult/child gets is smudged over, just like the line between fantasy and reality.

You could argue that these smudgings — the fact that the Snorklewacker occasionally escapes into the real world while Hobbes never does, or the fact that Calvin is always a six-year-old with a six-year-olds interests, while Binkley has anxious daydreams about economists — means that Calvin and Hobbes is the more true-to-life strip. I tend to agree with Bert Stabler, though, when he argues that Bloom County is in the mode of realism — especially when we use Ambrose Bierce’s definition of realism as “the art of depicting nature as it is seen by toads.” Calvin and Hobbes revels in creativity; Bloom County deflates it. Watterson creates a world from nothing; Berkeley Breathed insists that your flights of fancy will be fined.

Inevitably, Watterson’s self-vaunting optimism in the power of childhood and comics is the popular and critical darling, while Breathed’s dumpy skepticism is either ignored or forgotten. But for me, at least, I much prefer Breathed’s sly, exuberant pfft to Watterson’s rote magic. Certainly, I’d happily trade all of Watterson’s cosmic shenanigan’s for that single motion line Breathed uses to show the curlicue path of the ax, so you have to imagine the head flipping around before embedding itself in the wall. Or, for that matter, for that first picture of the happy Snorklewacker leaping up and down on the bed, a scrunched purple bundle filling the room almost up to the ceiling with jittery motion lines, imagination not as expansive power, but claustrophobic vibration.

Bloom County is realistic, I’d argue, not because it eschews fantasy, but because it doesn’t. In Breathed’s world, the real and the ridiculous crowd in on one another, elbowing each other for space in the same low-ceilinged room. Children are not proto-artists to be glorified, but just schlubs like the rest of us, beset in equal measure by the snorklewackers in their own brains and by the due dates in everyone else’s. The artist isn’t a god, but a horny toad, who provides, not wonder, but nagging, and an occasional ax.

_____

The entire Bloom County roundtable is here.