This review of America Gone Wild ran in The Comics Journal a while back.

America Gone Wditpsh

In his preface to America Gone Wild,” Steve Bell links Ted Rall to the illustrious tradition of American cartooning that began with Thomas Nast. It’s an odd comparison. Nast was a highly skilled illustrator with a knack for dramatic composition and striking images. His cartoons were instantly understandable, by literate and illiterate alike. As Nast’s nemesis, the corrupt machine politician Boss Tweed moaned, “My constituents can’t read. But, damn it, they can see pictures!”

Ted Rall, on the other hand, is a shockingly bad draftsman — one TCJ message board poster correctly noted that Rall’s drawings look as if he holds his pen with his sphincter. Moreover, his strips are wordy and unimaginative, often featuring little more than panel after panel of talking heads. In the introduction to this book, Rall claims that his visual drabness is a sign of iconoclasm. “Back when I first began taking cartooning seriously in the ‘80s, I had promised myself to throw out all the old rules,” he intones sententiously. “Gone would be Democratic donkeys and Republican elephants…the conceit that political cartoons should be single-panel, and the big head-little body school of caricature.” All of which would be a lot more convincing if (a) there were any sign that Rall could draw an actual caricature if his life depended on it, and (b) Gary Trudeau had never existed.

Personally, I sometimes wish Gary Trudeau had never existed — his half-assed graphics and smug whimsy have had a horrible effect on comics in general and on editorial cartooning in particular. And while he has inspired some great strips — like Bloom County — I can’t help feeling they would have been even better if it weren’t for his influence. Be that as it may, given the extremely confining limits of Trudeaudom, Rall’s drawings aren’t so awful. In fact, compared to Tom Tomorrow’s clunky collages, or David Rees’ lame clip art, or Trudeau’s stylistic nullity, Rall’s cock-eyed, snarling, anatomically unhinged characters start to look pretty good. It’s true that when Rall draws Ronald Reagan in Hell, it doesn’t look like Reagan, it doesn’t look much like Hell, and it’s not evocative in any usual sense. But at least the illustration is genuinely ugly rather than just bland. I can appreciate that.

Similarly, Rall’s jokes rely on boilerplate liberal outrage and are massively overwritten. But that goes with the territory, and, within those limits, Rall can be fairly funny. For instance, the gag in the Reagan-in-Hell panel is that Reagan’s in heaven — which now looks like the Pit because of budget cuts and privatization. “Funding Good Deeds to Cancel Evildoing”, in which Rall suggests that the U.S. should get the right to torture an inmate at home every time it frees a political prisoner abroad, is great gallows humor. Rall’s vicious portrayal of “Generalissimo El Busho” as a drooling, toothy coup leader is nicely done too, if that’s the way your politics swing. And the non-partisan Fantabulaman comics are entertaining, especially the one in which our invincible hero destroys a giant robot by mentally calling into existence 1000 barrels of acid rain. I like super-hero satires — so sue me.

If this were all there were to Rall, he’d be just another competent career gadfly, cheered by the lefty choir and ignored by most everybody else. But instead, and improbably, Rall is one of the most polarizing cartoonists in the country, extravagantly loathed by the whole spectrum of right-wing indignation-peddlers (Limbaugh, Colter, O’Reilly, etc.) and by a good portion of the comics industry as well. I mean, it would be one thing if Rall were a Marxist advocating violent revolution, or a Klansman spouting racial genocide. But he’s just a liberal. How does a moderately talented cartoonist with solidly mainstream views manage to cause such a ruckus?

His detractors would argue that he does it by being an enormous flaming asshole. His supporters — and Rall himself — maintain that Rall is a target because he’s a fearless, articulate opponent of the establishment, one of the few people with guts enough to point out that the emperor has no clothes. There’s probably something to both of these views. To me, though, they both ignore the most essential facet of Ted Rall’s art: its incoherence.

As I mentioned, there are some strips in this collection that are pretty funny. But there are also an embarrassing number that simply don’t make sense. For example, a cartoon called “Everything That’s Wrong: Case Study: The 1/13/05 New York Times” is a series of black blocks with arrows and captions, topped by a super-imposed, blurred-out newspaper article that is almost impossible to read. I had no idea what the hell was going on until I read the explanatory text added for this book, in which Rall informed me that he was attacking the NYT for burying a news item about the discovery of WMDs in Iraq. Rim shot, I guess.

Fumbling one punchline could be an accident; fumbling a series of them, as Rall does, starts to look like carelessness. A strip called “Inappropriate Emphasis Comics” makes little sense — and even less when Rall explains it’s supposed to be a blistering attack on cartoonists who bold the wrong words in their strips. Another cartoon shows Bush as the medieval king Henry IV asking penance from Jaques Chirac; Rall comments, somewhat bemusedly, that “No one understood this obscure historical reference.” In a strip called “Do You Know Where Your Children Are?” a character named Barbara has her baby snatched from the hospital nursery, then a series of children kidnapped by her ex-husband, then a child taken by alien abduction, and finally her last kid is stolen from her well-defended island fortress by a child welfare agency. And that’s the joke. Get it? (In his explanatory text, Rall notes — not all that helpfully — that “A spate of child kidnappings increased parents’ paranoia.”)

This last example illuminates Rall’s standing as a controversialist. As far as I can tell, the strip is meant to use absurd, exaggerated humor to poke fun at a widely touted cultural phenomenon — the equivalent of a humorist suggesting that people are relying on their Blackberrys to schedule their bowel movements. The problem is that the phenomenon Rall is caricaturing — child-kidnapping — isn’t a transitory news item, but a problem that’s been around for years, even decades (unless Rall’s talking about a particular, localized series of kidnappings, in which case, why doesn’t he say so?) Furthermore, the target of the humor is unclear and confused — is Rall making fun of the media for sensationalizing these stories? Is he mocking the paranoia of parents who are overly concerned about their kids being nabbed? Or is he mocking people who have actually had their kids stolen? You could certainly read it the last way — and if you did, you might well be extremely pissed off.

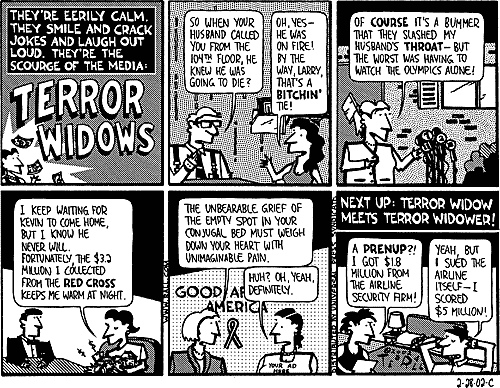

This particular cartoon didn’t get Rall any bad press, but those that did — most of which Rall discusses in his introduction — work in much the same way. For example, in his famous “Terror Widows” cartoon, Rall tried to call attention to the apparent hypocrisy of particular women, like Lisa Beamer, who parleyed the death of her spouse on 9/11 into lucrative media exposure. This is certainly explosive material, and Rall might have gotten flack for it anyway. The clincher, though, was that he never mentioned Beamer, or anyone else, by name. Instead, the cartoon reads as a vicious and arbitrary attack on anyone who lost a loved one on 9/11. In his introduction to this book, Rall acknowledges that he “should have referenced the original media whoring that had inspired the cartoon more carefully.” But he refuses to apologize, on the probably true but nonetheless irrelevant grounds that while “’Terror Widows wasn’t my best work…it was far from my worst.”

Rall’s refusal to back down here lends validity to the “asshole” interpretation of his career. But the fact remains that in almost every case where his cartoons have caused a brouhaha, it’s because of his incompetence, not his malice. “New York City Fire Department 2011” was meant to be a light-hearted goof about the number of donations New Yorker’s made to the firefighters after 9/11. Thanks to Rall’s ham-fisted writing style, though, it is possible to see it as an attack on the firefighters’ morals — and many readers did. Even more telling is Rall’s bizarre cartoon comparing the U.S. to a school run by a mentally-handicapped student. The strip ran after the 2004 election, and Rall intended the handicapped student to be a stand-in for Bush — I think. But the allegory is tenuous. Instead, what really comes across is the image of the barfing, drooling retard, and Rall’s suggestion that the mentally handicapped should be locked away so the rest of us don’t have to see them.

Rall got lots of angry letters from parents of special needs kids, and this time he did apologize. “Looking back on it now, I probably wasn’t in the best frame of mind to work my high-wire act on a piece of Bristol board,” he muses. Check. But the real problem here isn’t that he made one mistake, or two mistakes. The real problem is that, with apologies to Mark Twain, Rall sees as through a glass eye, darkly. Aesthetically, I’m not automatically put off by confusion, opacity, or offensiveness for its own sake and, from that perspective, I can enjoy Rall as a kind of aphasiac dada experiment. But even if some art doesn’t need to be clear or pointed, surely editorial cartoons should be. That’s why Thomas Nast, who could communicate without words, is one of the masters of the genre. Ted Rall, on the other hand, often seems unable to communicate at all.