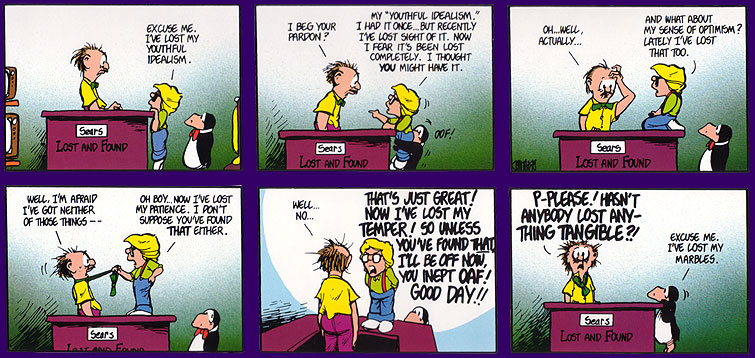

“This sort of thing–the mocking self-consciousness–confounded the poor newspaper editors. I thought everyone did it.”

—Berkeley Breathed

“I’d never read any comic besides Doonesbury,” Berkeley Breathed wrote, whenever people asked him about his influences. Reading early Bloom County and its predecessor, Breathed’s college strip The Academia Waltz, the dominant flavor is Trudeau: the sex & dating jokes, the political humor, the first faint touches of surrealism (talking animals aside) with Zonker descending, like Snoopy into his Doghouse, into the depths of two-foot-wide Walden Puddle. Though Breathed’s squash-and-stretchy, Chuck Jones artwork was always distinct from Trudeau’s thin lines, Trudeau was Breathed’s model for a comic strip: early on, he even unconsciously reused an entire punchline with Milo Bloom in the place of Mike Doonesbury. The two cartoonists later became friends, and by the late ’80s, the tables had turned: Bloom County influenced Doonesbury. After his 1984 hiatus, Trudeau followed Breathed’s lead, introducing more spot blacks, thicker linework, wilder camera angles, and surreal pop-culture parodies like Ron Headrest and Mr. Butts. (Trudeau was heavier-handed than Breathed; Trudeau’s parodies always had a point.)

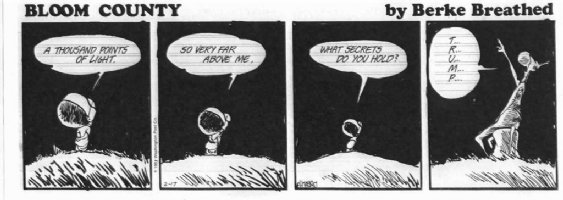

Bloom County reshaped the boundaries of American newspaper comics. Its appropriation of celebrity culture, politics and commercialism were the perfect expression of, and protest against, the booming ’80s. He used undisguised references to real people and things, real logos and real modified photographs; even Li’l Abner, the newspapers’ onetime satire king, had always hidden its pop-culture references and product titles under cheesy disguises (i.e. TIME+LIFE=LIME magazine), and when it featured celebrities (like Frank Sinatra) they were fawned-over guest stars, not subjects of mockery. In Breathed’s case his only restraint—the mellow heart of the strip—was a Shel Silverstein-like mix of whimsy and perversity, and an unwillingness to talk down to children.

But he was uninfluenced by comics apart from Trudeau; to hear Breathed tell the tale, he created Bloom County in a vacuum from the comics world, isolated after moving to Iowa City with his then-girlfriend. The over-the-top, Hunter S. Thompson-esque persona Breathed displayed on his dust-jacket bios was half true: apparently he really did prefer kayaking and flying airplanes to sitting at his desk reading comics and drawing them (though I suspect he watched a lot of daytime TV). Bloom County was not an exercise in nostalgia for comics past (like this article), or a self-conscious work of art burdened by the History of the Medium (like Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts). Nor did Breathed have any particular interest in his own fans, let alone the kind of “fan dialogue” and “community-building” that is a requirement for being an artist in the 2014 world of social media; although I’ve never heard of him being rude to a fan, he confessed in the catalog to the 2011 Cartoon Art Museum Berkeley Breathed exhibit that he didn’t really understand their enthusiasm at the time (he came to appreciate it later) and he was always nonplussed at things like book signings. Breathed’s lack of interest in comic strips allowed him to become one of their last true originals.

******

As an upper-middle-class child in coastal Northern California in the ’80s, I was a Democrat by default, although not from any deep political awareness: my issues were mostly fear of nuclear war (and thus of Reagan), and a kind of Al Gore “don’t build your houses near my house” environmentalism. I started reading Bloom County sometime in elementary school, probably because my friends brought the collections to school, and soon afterwards it started in the local newspaper.

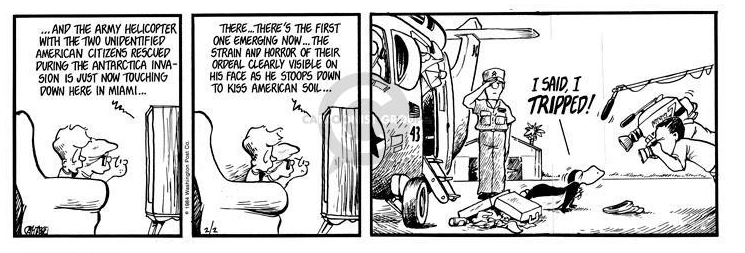

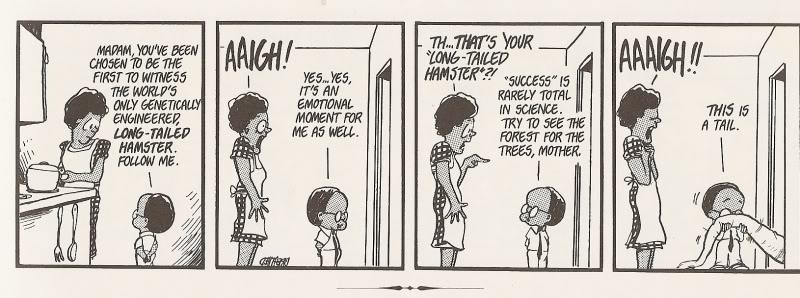

I was 10, the same age as the strip’s ostensible main characters Milo and Binkley, and Bloom County fascinated me. It had content I’d never seen in comics before: atomic mutants, plastic surgery, nuclear spills, cocaine, and scenes of the U.S. Marines invading Antarctica (“Operation Antarctic Fury”), running around chasing penguins and firing guns. It introduced me to people I’d never seen on the comics page, and some I wasn’t familiar with at all: of course I knew about Brooke Shields and Michael Jackson, but Geraldo Rivera, Mike Wallace, James Watt and Mick Jagger, to name a few, all came to my attention through Bloom County first. Lastly, it introduced me to words I’d never seen in comics: “hijackers,” “war mongers,” “imperialist pig.” In one early strip radical schoolteacher Ms. Harlow leads her students in a protest, ending with the gag of a little girl wearing a gas mask, “In case the fishes tear-gas me.” Harlow corrects her: “Fascists, dear.” I learned the words “liberal” and “left-wing” from Bloom County, although I wasn’t sure what they meant at first, since my only context were Breathed’s strips about “the vanishing American Liberal! Once they thundered across the American scene in great herds, but now they have been hunted to near extinction!”

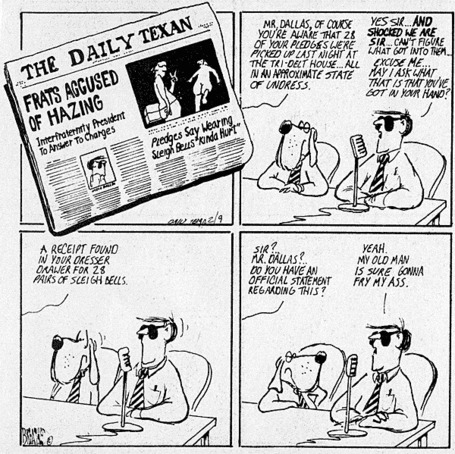

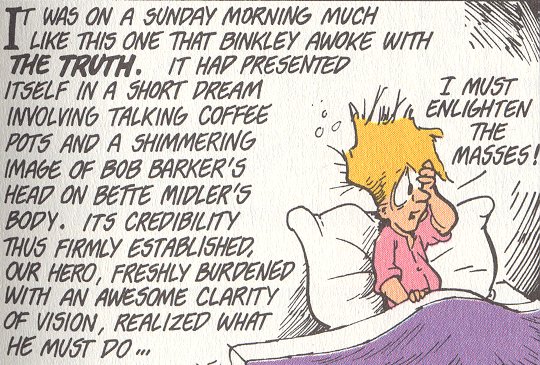

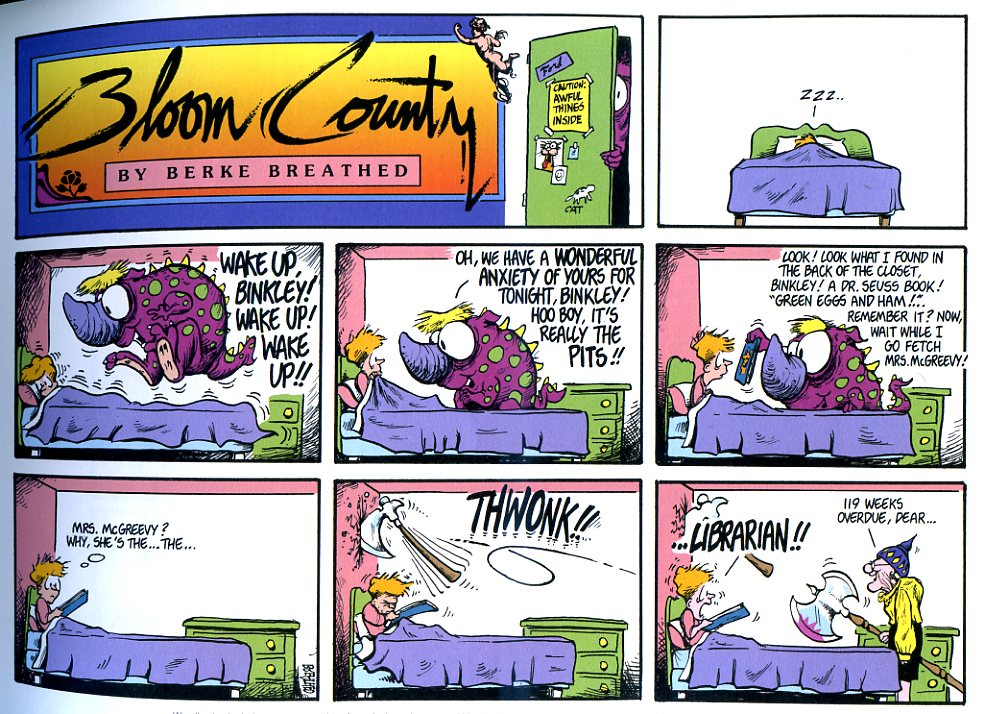

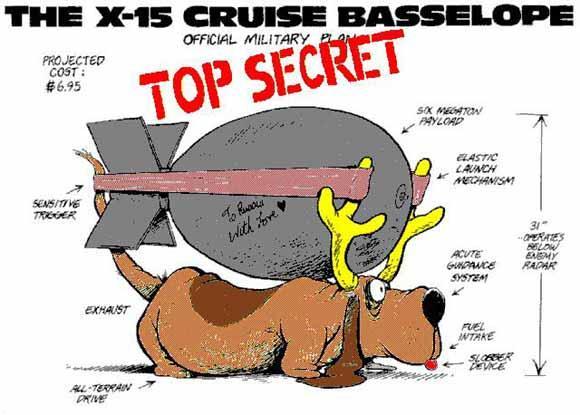

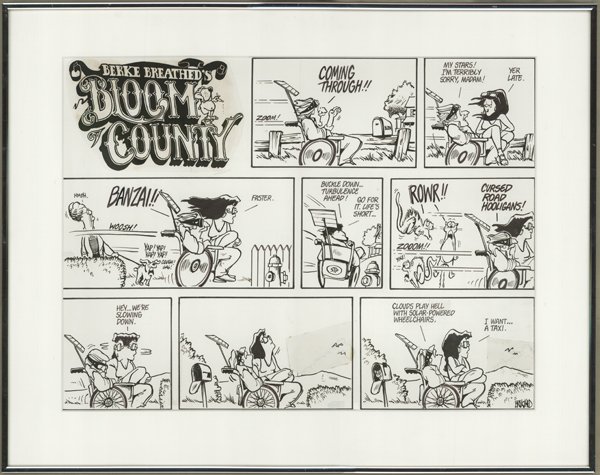

With underdog stubbornness and absurdist self-mockery, throughout the Reagan years, Breathed kept the liberal/leftist torch burning on the comics page. My mother, who started reading the strip shortly after I did, certainly got references that I didn’t; but even to me Bloom County was, as Li’l Abner might have put it, eddycayshunal. Although it’s not annotated by IDW, I remember exactly what scandal Breathed was parodying in the December 3, 1983 strip (when lousy politician Limekiller announces proudly of his campaign team “We’ve got every kind of weird mix you can imagine…a black, a woman, two dips and a cripple!”), because our elementary school teacher had used it as an inroad to talk about prejudice and affirmative action. Even to the most politically apathetic kid or adult, Bloom County’s other hook was that it was visually unpredictable, a break from the 1960s flat aesthetic popularized by Peanuts and enforced by the size of the comics page (and later, by Flash animation). Bloom County used camera tricks, fake advertisements and newspaper articles and other meta-play with the comics medium, and starred a variety of grotesques, hallucinations, dream sequences and monsters, the latter usually but not always birthed from Binkley’s Anxiety Closet. (Calvin and Hobbes, which came later, also had cool aliens and monsters, but was sadly lacking in machine guns and chainsaw murderers.)

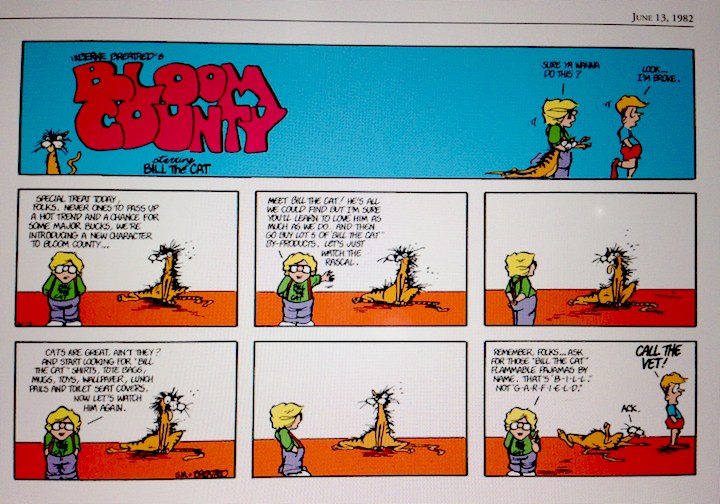

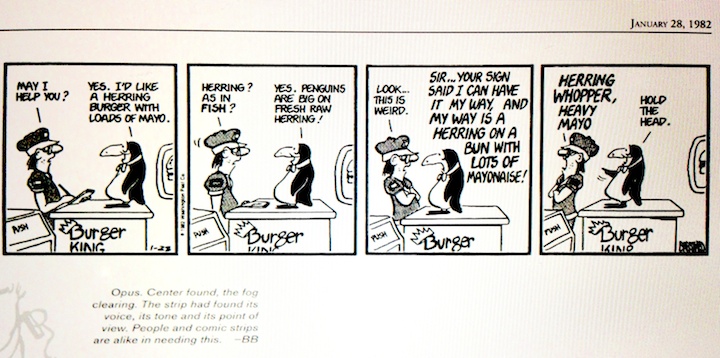

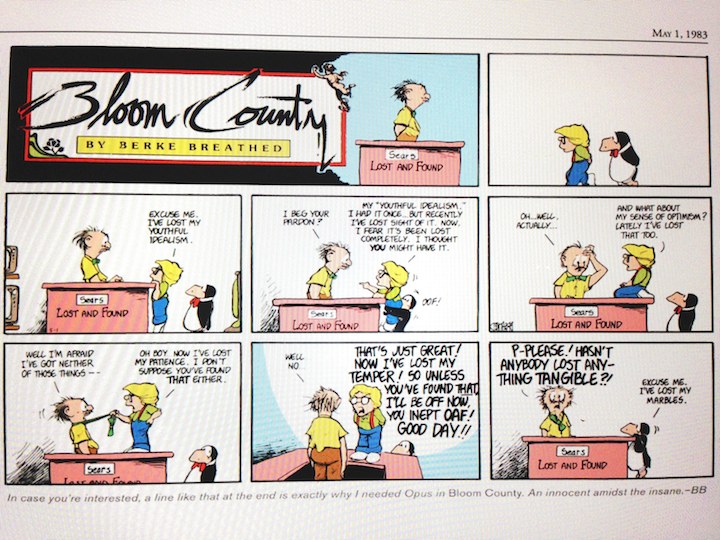

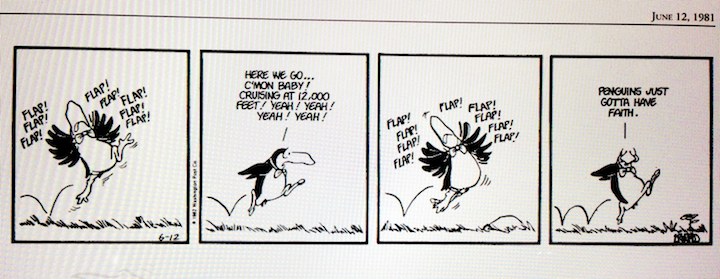

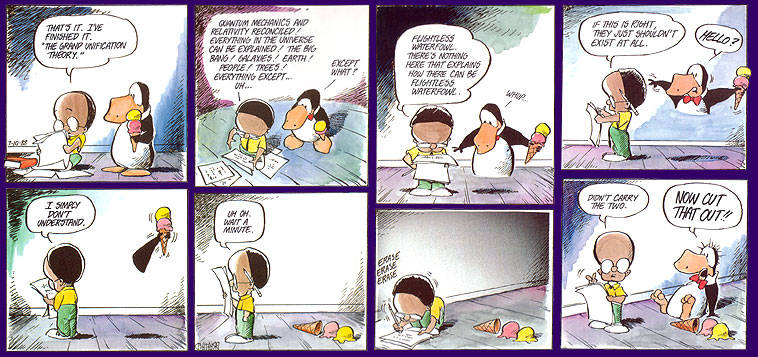

Like most comic strips, Bloom County took awhile to find its voice. The first collection from Little, Brown & Company didn’t come out ’till 1983, three years after the launch, and eliminated tons of material only reprinted in the complete collection from IDW. Apart from the then-undifferentiated funny animals, the strip started as a dialogue between Milo Bloom—young, liberal, cynical, an author-insertion character—and old Major Bloom, the gun-toting, Commie-hating, Patton-imitating right-winger. Major Bloom was joined, from then till the end of the strip, by a variety of other parodies of conservatives and rotten political types: Moral Majoritarian Otis Oracle; merely drunk and corrupt Senator Bedfellow; drunk, corrupt and poor Limekiller; and Republican fratboy lawyer Steve Dallas. Gradually the early characters departed, leaving their useful qualities to be distributed among the survivors. Major Bloom faded away, and his conservative politics were absorbed by Steve Dallas and the lesser animals (Hodge-Podge the rabbit and Portnoy the gopher). Milo never entirely left, but he became more of a coldly calculating newspaperman and politico; his functions as a romantic lead were ceded to two more sensitive characters, first hapless, Linus-like Binkley—introduced as a wimpy young dreamer who’s a perpetual disappointment to his macho Archie Bunker-like father—and then even more hapless, and thus more sympathetic, Opus the penguin. In 1982 Opus began to take center stage, writing his poetry, dreaming of flight, becoming the center of innocence in a chaotic world. With the introduction (and, in 1983, first death) of Bill the Cat, the drooling, brain-dead, bulging-eyed, cocaine-addicted parody of every celebrity imaginable (including Garfield, E.T., Little Orphan Annie, etc.), Opus had his partner and the strip had its core.

*************

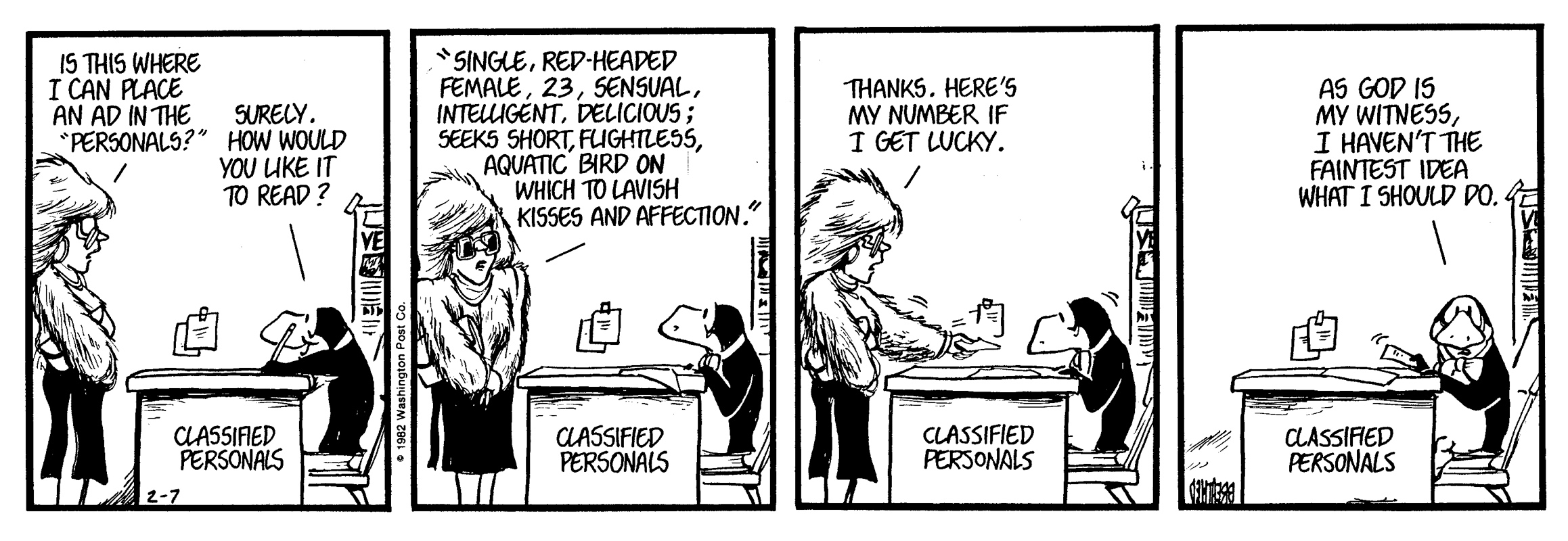

“Single, red-headed female, 23, sensual, intelligent, delicious; seeks short, flightless aquatic bird on which to lavish kisses and affection…”

Much of the later strip featured around long, tabloid-like melodramas about these characters—Opus & Bill’s 1983 presidential run, Opus switching places with Michael Jackson, Opus, Bill and Steve’s stint in the heavy metal band Deathtöngue—and this was another thing about Bloom County: it was the last of the great story strips. It wasn’t the only one of course, but for me in 1984, Doonesbury and For Better or Worse were too adult and boring (also, someone had drawn erect penises on all the characters in the Doonesbury book at the local library) and even back then, the oldtimers like Little Orphan Annie and Alley Oop were obviously preserved corpses, propped up and hideously embalmed. But my mother and I eagerly looked forward to the daily newspaper to see what was happening with Opus’ latest crush, or Oliver Wendell Jones hacking the Pentagon and going to jail, or Bill the Cat’s affair with Jeane Kirkpatrick. Other humor strips rarely kept continuity longer than a predictable week-long arc, but Bloom County had the cliffhangers and emotional tug of a soap-opera continuity (with Breathed’s typical snark: when Steve Dallas is kidnapped and then zapped back to Earth by aliens, the final caption for that day’s strip reads “To be continued! Or maybe it won’t! Ya never know, do ya?”). I had to read Bloom County every day because it always seemed like the next day Opus might wake up in bed with someone, or our heroes might be lost on their balloon flight over the Atlantic, or Bill the Cat might die (again). Towards the end of Bloom County‘s 9-year run the stories started to repeat themselves, and perhaps Breathed needed a break; but when he relaunched the comic as Outland (and later, Opus) and switched from a continuity-focused daily to Sundays-only, he removed one of the strip’s great appeals.

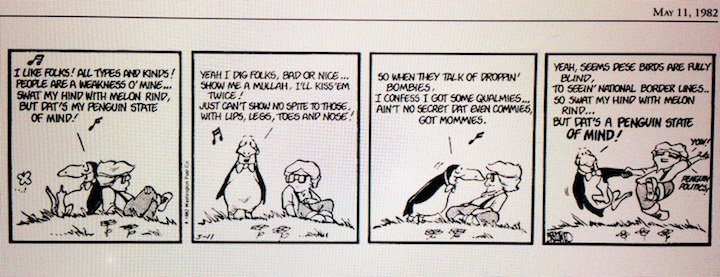

Bloom County bears some resemblance, apparently unintentional, to Pogo, another strip about politics and talking animals. Though more vicious in his satire, Berkeley Breathed shared Walt Kelly’s love of silliness and rhyme, as well as an innocent hero surrounded by incompetence and guile, and there is a similar charmingly rinky-dink feel to their respective storylines when the meadow/swamp animals ineptly attempt to run businesses and political campaigns. They also share another theme: love. Pogo Possum and the other male animals were always circling the star of the skunk Mam’zelle Hepzibah (the Love Goddess Ishtar of furry fandom), and Opus’ unrequited romances are the center of many plotlines; when not involved romantically, he’s pursuing another unattainable female presence, his long-lost mother, whom he first sought in 1984. Bloom County was exceptionally frank about love and sex, not to mention bestiality, as in the Greystoke parody with a half-disrobed Andie MacDowell wooing an as always half-comatose Bill the Cat (“Oo, Lord Orangestoke…it must have been so…so…terribly lonely…in that big…lush…steamy…sweaty jungle…”).

This was mind-blowing stuff to me at age 10. Unlike most newspaper strips which, if not about school or workplace, focus on families (typified today by Zits and Baby Blues—grandparents drawing comics for grandparents about their nostalgic memories of parenthood), Bloom County‘s emotional fixation was always dating and single life. Breathed was a young man. One of the early continuing characters was Bobbi Harlow, the schoolteacher whose defining traits were that she was an (attractive) leftist feminist in a hick town surrounded by chauvinist jerks; Breathed resurrected sexist fratboy Steve Dallas from his college strip as her antagonist and stalker. (Whether a difference of artists’ personalities and/or of late ’60s culture vs. late ’70s, the women in Breathed’s college strips generally come off better than in Trudeau’s, where they are more often just conquests or fanservice.) Through Dallas, Breathed mocked male machismo with a few Portlandia-ish detours to mock New Agey feminism (“There’s no need to be threatened by my womanhood…You turned your rear towards me, obviously an effort to deny a strong feminine presence nearby”). But Harlow started dating wheelchair-bound Cutter John (basically a Breathed self-insertion character) and slipped out of the comic.

Breathed introduced some other female characters, usually temporary, like shy, long-suffering teenager Yaz Pistachio (a sort of female Binkley), and Lola Granola, the free-spirited hippie artist who ends up fairly well-fleshed-out as a person who might consider marrying a penguin (over or because of her mother’s objections). But the strip mostly looks, mockingly or sympathetically, at the insecurities of men. Binkley’s Anxiety Closet, normally known for disgorging giant snakes and other monsters, surprises him one night with a beautiful woman demanding “Kiss me, Binkley! Kiss me like only a real man can kiss! I want fireworks, Binkley…I expect nothing less from the men of today!” Prepubescent Binkley ducks and hides under the covers. Though Breathed never degenerated into pin-up fanservice and “guy humor” (and even worse, “nice guy” humor) like Frank Cho’s blatant Bloom County imitation Liberty Meadows, Bloom County falls into the long cartoon tradition of a world where women are humans and men are (mostly) talking animals and monsters. And children.

****

“I will probably go out on my sword one day, insisting on a particular strip running despite the furor. One day.”

—Berkeley Breathed, May 2007

Al Capp, whose Li’l Abner was considered liberal in the ’40s but which changed by the ’60s into a vehicle for Capp’s grumpy and increasingly vehement right-wing politics, claimed in the foreword to his career-retrospective anthology The Best of Li’l Abner that it was liberalism, not he, who had changed: “I turned around and let the other side have it.” Berkeley Breathed never got conservative, but he did get grumpy (or grumpier, considering his always-slightly-ornery public persona).

<"There are no sacred cows (although perhaps penguins) in Bloom County,” reads the back cover text on the 2009 IDW edition Volume 1, suggesting that it was infamous in its time as some major boat-shaker. But although its groundbreaking nature is undeniable, I don’t remember Bloom County being particularly controversial in the ’80s: not like, say, Dungeons & Dragons (ignored by Breathed), heavy metal (affectionately parodied), Stephen King novels or video games (mocked scornfully). A google search for 20th-century Bloom County controversies and censorship doesn’t turn up much, except for grumbling from frequent targets like Mary Kay Cosmetics and Donald Trump, and newspapers changing “Reagan sucks” to “Reagan stinks” in a November 1987 strip. (Breathed responded “Today’s youth have long since legitimized the word.”) Breathed never charged suicidally into the windmill like, say, Bobby London; Bloom County was, like any newspaper strip had to be, a strip a 10-year-old boy could read at breakfast with his mother. In the annotations to the IDW edition, however, Breathed repeatedly points out strips he “couldn’t get away with nowadays.” In a 1981 strip poking fun at victimization and censorship (ending with the censors’ horrified realization “My gosh…LIFE is offensive!!”) he digs in the point with the 2009 annotation “It must feel very empowering to be offended all the time.”

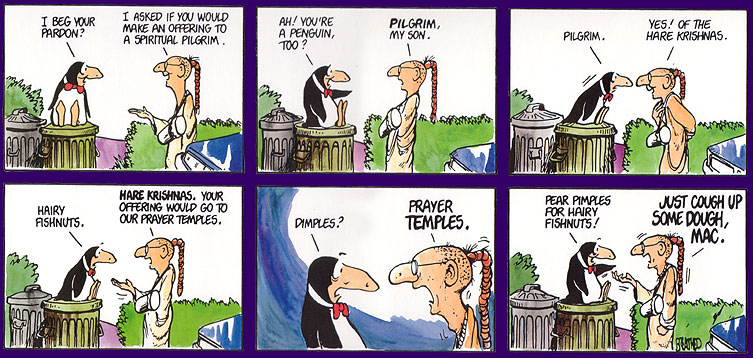

The rebranding, however slight, of Bloom County as a firestorm of political incorrectness presumably comes from Breathed’s own experiences at the end of his newspaper-strip career. In late summer 2007 two Opus strips jumped into the headlines when the Washington Post, Breathed’s home syndicate newspaper, refused to print them due to their satire of Islam (specifically through a white American convert, presumably an attempt to decouple religion from race). Breathed had mocked religion before, such as the Hare Krishnas in 1982, the “Bhagwan Rajneesh Cult Center” in 1984, and Christian fundamentalists, always. Although Breathed did not retire Opus until a year later, to hear him describe it in later interviews, listening to his publisher at the Washington Post relay concerns from a Muslim staffer about how much hair should stick out of Lola’s hijab convinced him that it was impossible to write the strip the way he wanted anymore. (“I thought that I saw it coming and approached it with probably more sensitivity than I am known for. I was not mocking anything about the Muslim dress—I was mocking the reaction to it,” Breathed said later.) Opus became a punching bag of the grotesquely partisan media landscape of 2007-2008, when Sony Computer Entertainment could recall the video game Little Big Planet for fear of offending Muslims with Quranic verses in the music (in a soundtrack created by an African Muslim musician), while right-wing news channels unapologetically stoked fear stories of American mosques and Obama’s “closet Muslim” religion.

To my eye, looking back over the old strips, Breathed does a good job of walking a delicate tightrope: creating a true Gonzo comedy, a broad satire of humanity, without veering into sexism, racism and stereotypes. At least not nonselfconscious ones. Throughout the strip Breathed made a strong effort to include African-American characters in a noncaricatural way, both in jokes about racism (mocking Diff’rent Strokes, the “Michael Jackson Caucasian Kit,” etc.) and race-neutral contexts. Oliver Wendell Jones, the 10-year-old genius computer scientist, was the Schroeder of the strip and one of the core cast. On December 11, 1983 Breathed reused an old daily strip joke as a Sunday strip with Oliver Wendell Jones and his grandfather in what had been Milo and the Major’s roles. Later, less successfully, Breathed introduced Ronald-Ann Smith, a poor black girl from the inner city, who was intended to be the main character of Outland; but in this case Breathed seemingly found it too difficult to make her a character rather than just a symbol, and she faded out of the strip (like all of the new Outland characters, for that matter). (The true fusion of Bloom County with African-American issues ended up being Aaron MacGruder’s The Boondocks, openly influenced by Breathed.)

Breathed wasn’t above using stereotypes to tell an essentially anti-stereotypical message, as in a late Academia Waltz strip when an Iranian-American calls his brother in Iran to beg him to stop burning American flags on TV, so he himself won’t be beaten up by bigots like Steve Dallas. (“Allah help me…it is fratboy!”) Garry Trudeau had introduced the first (openly -_- ) gay character in mainstream newspaper strips in 1976, but it was still very unusual in the early ’80s when Bloom County made fun of homophobia, in the recurring storylines in which TV preachers torment Opus with crusades against “penguin lust.” (“The biggest moral threat to the very moral fiber of our immoral society…penguin lust!!! Nothing but urges from hell!“) In elementary school I didn’t get this joke, although neither did I get the joke when the heroes go to San Francisco for a political convention and stay at a hotel run by a pair of bondage-loving leather daddies. In Bloom County one finds the occasional one-panel of a wacky Asian chef with Ginsu knives, or Milo disguised as an oil sheik to entrap a politician (“Want some dough, O fat one?”). But Breathed didn’t merely parrot the default American stereotypes, as demonstrated in a 2006 Opus strip in which he included a threatening, bazooka-wielding IDF soldier among a bevy of turbaned terrorists springing out of Opus’ Anxiety Closet of Modern Fears. Outnumbered five to one by turbans, but still enough to anger conservative bloggers, like the 2009 Doonesbury Old Testament joke that provoked a disapproving letter from the ADL.

When Breathed quit newspaper comics in 2008, he cited frustration with things like the 2007 Islam controversy, and another incident he mentions in the IDW annotations, when the Washington Post “shut down my gentle mockery of Scientology in 2008” (apparently completely shut it down, since no mentions of Scientology appear in Opus strips in that year as far as I can tell). He blamed the partisan political climate and the timidity of newspaper editors. It’s difficult not to wonder how long Opus would have kept going in any case, since Breathed, like many aging newspaper strip artists, had long expressed frustration about the dwindling relevance of newspapers, and had twice before canceled his strips in an attempt to switch over to children’s books and other media. Like the other major comic strip artists who arose in the ’80s, Bill Watterson and Gary Larson, Breathed had a completely different attitude towards his art than the strippers of earlier generations: i.e., it’s better to stop while you’re ahead than to beat the horse ’till death and beyond.

Tim Keck, co-founder of The Onion, recently said in a lecture that the changing relationship between media and audience makes it harder to use edgy humor with a mass audience: the same hyperconnected social media that makes it possible to, say, fund Kickstarter projects also makes public outrage/disapproval much faster, stronger and harder to ignore. In the 2010s, artists are assumed to be in constant communication with their fans, and the kind of outsider distance that artists like Watterson or Breathed had in the 1980s—Breathed once said he wasn’t aware when Bloom County had become popular until many months later—whether a disadvantage or an advantage, seems quaint. Similarly, the things Breathed pioneered on the comics page—the combined mockery of pop culture and politics, the intermedia visual play with altered photographs, hoax headlines and ads—are now commonplace (if not as well done as Breathed did them), easy to make with Photoshop and fast to upload into memes. (And as a result of their instancy, sadly, they’re rarely strung together into the hilarious narratives and recurring characters Breathed did so well.) Like much about Bloom County, it’s easy to look at these things and think, “ahh, how ’80s!”; but Breathed himself would probably resist casting the book as a mere piece of ’80s nostalgia. Breathed’s Bloom County was a work of genius, but it was never nostalgic; as long as it is controversial, it is current. Old comic strips, like all old comedies, have power when they are humor, not humored.

_____

The entire Bloom County roundtable is here.