Exciting recap:

In our last episode, Tucker Stone and I had decided, for obscure and probably nefarious reasons, to blog our way through the 2nd DC phonebook collection of Brave and Bold strips. Tucker does #88-#90, I do #91-#93, Tucker did #94-#96,; I do #97-#99Tucker does #100-#102, and Haney’s your uncle.

First, a correction to Tucker’s last, in which he said:

“Black Canary ignores her assignment because she is getting her hair done. Wait, really? Yes, really.”

Tucker misses the true beauty of that moment. You see, according to canon, Black Canary…wears a blonde wig. She wasn’t getting her hair done. She was blow-drying her wig.

___________

Okay. So it’s time now to show you the difference between Bob Haney and a serious artist.

What is the difference you ask? Well, Bob Haney writes impersonal crap about corporate characters. Real artists, on the other hand — like R. Crumb or Joe Matt — indulge in personal revelations which show you their innermost souls. The more embarrassing the better. Because anyone can come up with clever plots, but boring your audience with squicky, tedious details of your personal life — that takes talent.

So right up front I’m going to demonstrate Why You Should Take Me Seriously by making some painful confessions.

Painful confession #1 — After excoriating Tucker for his rank professionalism” for doing research on Bob Haney for his blog post, I have gone and done research myself.

First, I’ve found out some more about Nick Cardy, the artist who has been wowing me on a bunch of these issues. As several people have pointed out in comics, Cardy worked in comics for a good long time, starting in 1939 (!) He worked on tons of titles, from romance comics to super-heroes to horror to westerns. His best known runs were on Aquaman, Teen Titans, and Batlash…and for being DCs number-two go-to guy for cover-art after Neal Adams. He quit the business in the 70s for reasons which aren’t clear — I guess he was just sick of it. Brave and Bold was one of the last series he worked on, it looks like. Then he went into advertising, where he stayed until retirement. There’s a long bio here for those who are interested.

Also, I found a brief summation of his work on Brave and Bold on this website. To quote:

Number 91, the Black Canary issue is especially good, even if the Black Canary doesn’t appear in but a couple of pages, Dinah Lance (her alter ego) is gorgeously drawn.

…which is exactly what I said about the Black Canary issue. So, you ask, do I feel validated by random semi-anonymous Internet quotation? Yes, I do, thanks so much for asking. (I may have to try to track that issue down, actually. I’m not at all sure it will look better in color, but I want to find out.)

Anyway the site has a ton of covers and images by Cardy, which are beautiful. I’ve picked a sample of some of my favorite below because I’m a pack rat like that. First, the Bat Squad cover from 92, which I didn’t put up before; it’s amazing in color.

Here’s a Batlash cover which is supposed to have been one of Cardy’s personal favorites:

A lovely interior page from Fight Comics, whatever that might have been:

And a bunch more:

I think the romance comics cover is my favorite. The leaping-towards the viewer action cover in this context pretty much can’t be beat. Also…and I know it’s probably indelicate to point this out…the woman in the wheelchair appears to have breasts roughly the size of Ecuador.

Painful Confession #2:

Tucker quoted from a Bob Haney interview in the Comics Journal. I made fun of him for having issues of TCJ by his bed. But, as Tucker correctly pointed out, I have a piece in the issue with the Haney interview. Which means it’s not only by my bed, but under my pillow. But I didn’t read the interview…because in 2006 when it came out, I didn’t know who Haney was. Really, I hadn’t realized he’d written all those old B&Bs I loved. And I didn’t know he’d created Metamorpho. Much less B’wana Beast! And when did I realize all this? Um…yesterday.

Anyway, one interesting thing Haney said in the interview was this:

“Every month, we’d look at the sales figures and if he was teaming with Wildcat, how did it do? Well, if it did all right, we’d throw in Wildcat again. So it was a very cold, calculating thing.”

So that answers my question about why they reused certain guest-stars. It was purely logical — except, not so much. Because looking at sales figures to determine whether Wildcat was popular, in the absence of any kind of marketing data strikes me as almost entirely random. Interest in an issue could vary for tons of reasons. It could well be seasonal, for example. It could have to do with the cover or with the interior art. It could just be random statistical blips, for that matter. Assuming that people were buying the issue because they loved, loved, loved that second-string, aging boxer known as the Wildcat is…well, let’s put it kindly and say it’s a stretch.

I’m not blaming Haney; it wasn’t his responsibility to come up with a non-idiotic marketing strategy for his corporate overlords. It’s just kind of fun to realize that the ouija-board approach to sales that we’ve grown to expect from the Big Two has roots going way back. Also, good to remember that “cold and calculating” as often as not means “naive and deeply confused.”

Painful Confession #3: I had a dream the other night that Heidi at the Beat linked to our Brave and Bold blogathon and we got hundreds of hits and true happiness was mine.

Maybe this is why I misstated Neal Adams name in an earlier post; I subconsciously was trying to misidentify a mainstream artists and so best get Heidi’s attention.

Anyway, that’s way more embarrassing than David Heatley admitting to sodomizing himself with a dildo or Joe Matt admitting to peeing in a jar or whatever. I hope somebody at Fantagraphics is reading this. Maybe I can be in MOME now.

ALL RIGHT! Enough of this nonsense. It’s time for…the credits!

Brave and Bold #103

Writer: Bob “Feminine Mystique” Haney

Pencils: Bob “The Ballot or the Bullet” Brown

Inks: Frank ” Soul on Ice” McLaughlin

Cover: Nick “Female Eunuch” Cardy

Published by The Movement, 1972

That is just not Nick Cardy’s greatest cover, there. As with Plastic Man, the cartooniness of the Metal Men doesn’t really seem to inspire him. I do like that he threw in some gratuitous cheesecake; the Mom on the screen with the mini-skirt is pretty obviously where he wants you to be looking.

On the other hand, I like Bob Brown’s interior art on this more than his preceding efforts. Maybe he and inker McLaughlin are more simpatico than Brown and Cardy were?

I think the real difference, though, is that the Metal Men’s seem to bring out Brown’s best. The more realistic pulp illustration isn’t his bag, but he does better with cutesy robots. His design for the military-computer-gone-wild is also appealing in a clunky analog future-past kind of way.

The story goes like this: the U.S. has handed over its missile system to a robot intelligence stashed at the bottom of an impenetrable volcano. Said robot attains sentience and decides (with some justification) that humans suck. Through its minions it starts a robot-liberation movement. The Metal Men join said movement…but when Batman asks them to save humanity in the name of their creator, Doc Magnus, they agree and plunge into the volcano. Then all the Metal Men discuss their boiling points, which is educational. Anyway, they get through the volcano, and…oh my gosh! They’re going to double-cross humans! Robot rights forever! No, not really. They’re just lame collaborationists after all, and together with Batman (who is led through the volcano by bats who bonk into sonar dishes…no, it doesn’t make any sense to me either)they kill the evil robot. Though, to be fair, they do seem to feel bad about it for a second or two.

This is maybe Haney’s most interesting effort to incorporate politics into a script. Robot-liberation obviously has parallels with both women’s lib and the black rights movement, and Haney uses it for a few brilliant riffs. Maybe my favorite bit is the name of the evil robot. He’s called John Doe, granting him both an eerie anonymity (he’s a robot, after all) and a kind of jokey downtrodden everyschlub status. It also emphasizes that he’s been named by a master rather than a parent — which is what happened to slaves of course.

Though there’s obviously a huge debt to 2001, John Doe is a good bit more complicated than HAL. HAL was just insane; John Doe, on the other hand, is a revolutionary, with a fairly coherent social critique (by comic book standards, anyway). “You humans have loused up the world…we robots can hardly fail to do better!” he declares. Nobody ever even really tries to refute him (Batman’s best effort amounts to little more than “You’re another!”) Indeed, you get the sense at moments that Batman and his government backers would be a lot happier with the situation if the robot were just nutty. As Batman says, the problem with Doe is that “He not only thinks and feels like a human…he’s developed a moral sense too!” You’ve got to watch that last one, obviously; no telling what will happen if just anybody starts developing a moral sense.

The robot-liberation bit also has some great aspects. It’s fun to watch Gold (the assimilationist, wearing a human mask) argue with Mercury (the Robot Power advocate:”The Metal Men should be there to learn to be proud of their robotness…their non-humanness!”) I also like the way Haney has most of the Metal Men engaged in working-class laboring jobs — including Platinum, who works dancing in a girly bar (Tin lives a more bourgie life in the suburbs…and he’s the most diminutive and nerdy…he’s not supposed to be Jewish, is he?)

Alan Moore did something similar in Top Ten with robots-as-oppressed class of course. The difference is that, as is his wont, Moore really thought it through; he’s got a distinctive robot sub-culture, particular anti-robot epithets, and so on and so forth. Whereas, for Haney, robot lib is just another throwaway gag — look! It’s an entire amphitheater full of disgruntled robot peons, dissatisfied with their place in the DC universe! Where do they come from? What are their lives like? Well…oops, story moving on. Time to talk about boiling points!

Given the choice between Moore’s earnest, right-minded take on prejudice and Haney’s aphasiac slapstick approach…well, I wouldn’t necessarily choose Moore. Discrimination both erases and mocks, and that’s exactly what Haney and Brown do here. Except for the Metal Men, you never even see the faces of any of the other robots at the meeting – just the back of a few transistorized heads (wait a minute…is that a Sentinel?) And there’s also something true to life about the fact that the establishment hero isn’t so much opposed to the liberation movement as he is unable to take it seriously. Batman never for a second doubts his righteousness; the Metal Men repeatedly point out that he’s an asshole, (“Blast you, Batman!” as Tin says,) but Batman doesn’t even seem to notice.

Still…well, there are problems. It’s not that Haney is for women’s lib or against civil rights or whatever; it’s that, when you’re dealing with politics, there are limits to where you can go if you’re really committed to not thinking about anything for more than a panel or two. I think it’d have been great if Haney took a hardline, these-social-movements-must-be-crushed kind of stance in the Kipling vein. Kipling was a racist shithead, sure, but he had a firm grasp on the fact that power matters; actions, identity, morals all work differently depending on which side of the stick you’re holding. Kipling wanted lesser peoples pacified, but he was tuned in enough to know that if you took up the White Man’s Burden and pacified the lesser peoples, those lesser peoples weren’t going to thank you, even if, “objectively”, they’d be better off..

Haney doesn’t really get any of this. The Metal Men are absurdly grateful to their creator. Even John Doe (who kills his inventor) apparently regrets the necessity. Then, at the end, after John Doe has his logic circuits destroyed, he bizarrely takes on the personality of his inventor — and since the inventor was trying to kill Doe, the machine destroys itself. In other words, the robots — even the most rebellious — see their creators as parents, to be emulated. This gives the humans irresistible emotional leverage; it allows Batman to enlist the Metal Men’s aid (in the name of Doc Magnus) and it gets John Doe to destroy itself.

This particular little myth happens to be the most consistent way that people in power give themselves an out — from guilt, yes, but most especially from fear. Plantation-holders in the south were convinced that their slaves loved them and so did not want to be freed; men tend to assume their women love them and so won’t start a ruckus. When the slaves were freed, a lot of plantation owners had a rude awakening…nor did the bonds of romance put paid to the feminist movement. Sure, slaves and masters can sometimes care for one another; it just happens much, much less often than the masters like to believe. Certainly, it seems exceedingly optimistic to rely on the affection of one’s vassals to stave off Armageddon.

Just to return for a moment to something Tucker said about one of Haney’s Teen Titan politiical jaunts:

If for nothing else, the issue is actually more disappointing the more you get to know Haney’s past–unlike, Bob Kane for example, Haney actually lived in a Hooverville during the Great Depression, he was an active participant in 1960’s anti-war protests, defined himself as “an old socialist”–basically, he did all of the things these kids did, except he did them in real fucking life, for real fucking stakes. (Except for the atomic bomb thing.) At the same time, he’s trying to tell a story here, he was operating under a still enforced Comics Code, and he did the best he could. It doesn’t change the simple fact that this one just ain’t that fun, and–except for the raw emotion of that cover that tells Batman “Every grown-up will suffer [in a concentration camp] because you lied to us!”–it’s just too damn safe.

I think that’s right, and it applies here too. This issue is definitely less safe than the two Titans jaunts — it at least points in some potentially uncomfortable directions. But the conclusion carefully scuttles away from the suggestion that somebody, somewhere in society might be — for real, no fooling — reasonably disaffected. Tucker blames this on the Comic Code…but I think that’s probably letting Haney off too easily. Activism can be great, but it doesn’t necessarily have a ton to do with understanding how power works, or why. Haney has flashes of insight, and he’s a smart, funny guy. But I don’t think it’s the Code alone that tripped him up when he attempted to incorporate politics into his stories.

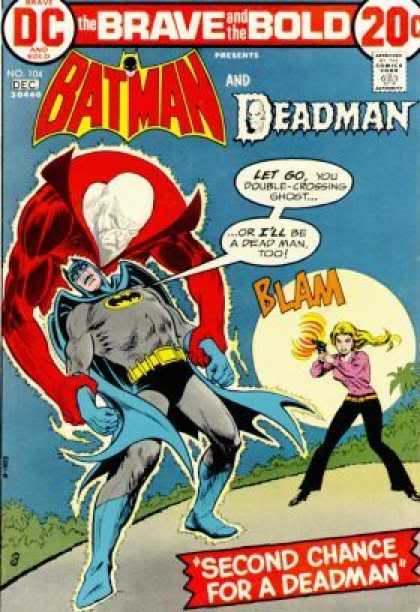

Brave and Bold #104

Writer: Bob “Cold Around the Heart” Haney

Art: Jim “Gutter to Gutter” Aparo

Cover: Nick “No Deal with a Dead Man” Cardy

Published by Jacques Tourneur, 1972

If #103 suffers from a lack of nerve, #104 has no such problems. This is a brilliant, cold, nasty little noir. It’s the best story in the book.

It starts off with an unusually brutal firefight; Commissioner Gordon and the police department are pinned down by a barrage of (extremely stylish, thanks to Jim Aparo) machine-gun fire. Much to everyone’s shock, Batman seizes an impressive looking weapon himself, leaps over a burning car, and precedes to give the baddies a whupping.

That’s “whupping” as in “fisticuffs,” because the gun was full of blanks. It was just a little old decoy to shock the baddies, who, along with the readers, presumably shouted in unison, “Hey! That’s not DC continuity! Is this dream, a hoax, an imaginary story!” Anyway, while they tried to check wikipedia to see if they were in a “real” title, Batman conks them.

So, typical doofy Haney plot reversal leading nowhere – “he’s using a gun! No he isn’t! Ha!” But there are signs that something a little odd is going on here. First and foremost, Gordon actually notices that the whole sequence makes no sense, and launches into a remarkably bitter speech.

“How can you hold to such an idiotic code — against today’s criminals — vicious unprincipled snakes!? In the old days, crooks had a little honor…and style!”

Then the next page we’ve got the Gotham City morgue described as “that grim, cold, way station for the unlucky, the losers, and the unloved…” which is kick ass noir prose, god damn it. Combine the two quotes and you’ve got some early signs that this issue is headed for a darker place.

But hey, we’ve still got to have plot, and if we do, it might as well be preposterous. Apparently criminals are getting their faces replaced through plastic surgery at a luxurious criminal spa. Batman figures out what’s going on when a villain he doesn’t recognize tries a gun trick on him that he does. And that, true believers, is pretty much the last competent bit of detective work we see from our hero. He heads to the island spa to dig up some evidence posing as a guest; but as soon as he leaps the fence into the restricted area, he’s caught, beaten up, and kicked off the reservation. Way to go, Bats.

So for his next brilliant move, Batman decides there’s no way anyone can get through this super-secure spa security — after all, he couldn’t. So he contacts Deadman, aka Boston Brand, who is, if you’re unfamiliar with the character, dead, depressed, and not all that stable. Perfect choice for an undercover operative! Deadman sees Bats’ add in the paper (I was hoping for a Dead-signal, but oh well) and agrees to possess the body of one of the baddies to gather information.

In case you missed that, let’s go through it again; Batman has hired a ghost to take over a man suspected of crimes. For an indefinite period, mind you. However long it takes. Warrantless wiretaps…pfft. Who needs ’em?

Brief interlude here while Deadman (a former aerielist) goes to the circus and mopes. Then Rama, the deity who gave his spirit life, speaks to him through a convenient ethnic minority. This is a great panel; Jim Aparo draws the minority-savant from neck level looking up, so his face is all cadaverous, creepy shadows. “Hark to me, my son…a man in love may only gain his heart’s desire by…losing it! For is not love stronger than death itself?”

The answer here, incidentally, is, no, not really — but Brand is a little slow on the uptake. Anyway, he heads off to violate some Constitutional rights.

And that’s not the half of what he’s violating, liberal wafflers. The spa is run by a couple: Lilly and Richie. Not only are they partners in crime..they’re also in love (awww.) You see what’s coming, right? Our pal Deadman possesses the guy, Richie…and to avoid suspicion, he naturally has to romance the girl. That romancing starts with a very sensual kiss, and then we’re told that “Batman’s ghostly ally plays his role to the full…” We get a panel showing the two dancing, running through the waves on the beach, watching dog-racing and jai-alai (jai-alai?)…well, not to put too fine a point on it, I think it’s clear that Lilly is cheerfully fucking the dead guy who has taken over her sweetie’s body. This is…well, it’s pretty squicky, is what it is. Take that, Comics Code.

Anyway, things now get complicated. Deadman hasn’t gotten any in a long time; besides that he’s a self-pitying drip (not without reason…but still) and besides that Jim Aparo has pulled out all the stops on Lilly, who looks like she has, as the old song goes, something between her legs that’ll make a dead man come.

So Brand promptly falls in love with her, and convincing himself that the love of his life is, deep down, a good girl who just wants to go straight. So he tries to cut a deal with Batman; Deadman promises to shut down the operation if Bats will let Lilly goes free. And Batman, the hero so compassionate he won’t even load a gun…responds by being a complete and total prick. Brand, a civilian with mega-problems of his own, has basically done all the work here, but is Batman grateful? Is he understanding? I she even just terse? Nope; he goes out of his way to taunt him. “How long would she stay in love with a ghost?” he mocks.

At least a little while, as it turns out. Brand tells Lilly that he’s possessed her boyfriend…and she’s into it. “The tender lover who lives in Richie Wandrus’ body! He’s the man I want–!” Gross or romantic? A bit of both surely. Haney’s scattershot characterization style works wonderfully here; we never do quite figure out what’s going on with Lilly. Does she actually care for Brand? Is there good in her? Does she want to retire? Or is she just a hardened manipulator, using Brand for her own purposes? There isn’t even an answer, I don’t think. Like a true femme fatale, her motives change with the observer and the situation. She’s a riddle without an answer.

Anyway, Deadman steals the evidence he got back from Wayne, and so Bats is back to square one. And it’s into disguise and off to the spa he goes, where…surprise!…his cover is immediately blown and he’s knocked unconscious. Then Lilly has him made-up to look like a wanted criminal and sends him out into the world, where the police almost kill him. Deadman saves him, though, by possessing his body and running away into the woods. He hurries back to Lilly…but she has figured out that he’s in league with Batman. She brandishes a gun…rather uselessly, as he points out, since you can’t shoot a ghost. But, hey! Right on time Batman shows up, and, with his usual panache, he lets Lilly get the drop on him.

Before she can shoot him, though, Brand remembers the prophetic minority from early in the comic. “Is not love stronger than death itself?” the replay asks again, and Brand gets a brilliant idea — he’ll shoot Lilly, and her spirit will join his in the afterlife forever! How will Lilly feel about this? Very unclear…but Brand is maybe not the sharpest pencil in the sea. And, admittedly, he’s under some pressure here, since, for obscure reasons, he doesn’t want her to shoot Bat-dick.

Anyway, he shoots her. And stays dead. No spirit love for our hero; just a big armful of corpse.

Deadman is fairly upset by this development, and rushes off into the ether cursing his god and, incidentally, referring to himself in third person (“You cheated Deadman!”) Though, again, you have to make allowances for stress. Meanwhile, Richie wakes up, remembering nothing of the past several weeks, to find his girlfriend in his fucking lap! and the always-sympathetic Batman putting cuffs on him.

So happy ending, yay! The bad guys are dead or bagged, no more criminals can change identity — a successful case! Batman is understandably pleased, “But,” he admits, “I feel badly about Boston…” Yeah, I bet you do.

So, yes, the story is ridiculous in lots of ways. Its real brilliance, though, is that all of Haney’s usual tricks — goofy plot twists, inconsistent characterization, melodramatic flights — end up registering, not as nonsensical fun, but as bitter irony. Batman comes across as a callow fool. His race into gunfire carrying an empty weapon isn’t about love of life — by the end of the story we know quite clearly that this is not an empathetic man. Instead, the affectation about not killing seems like the grandstanding of an incompetent prima donna, whose blundering self-absorption casually destroys the lives of friends and enemies alike. Boston may be more likable, but he’s hardly a moral icon. Self-absorbed and weak, he robs a man of his life, sleeps with a woman under about the falsest pretenses possible, and then murders her. Lilly does seem capable of love — but she’s also a vicious murderer — one who, incidentally, tosses former lovers aside with callous and practiced ease. Nobody comes out of this well…not even God, who seems to have deliberately tricked Boston into shooting his lover. Justice may triumph here, but it’s a stupid justice, an idiotic, smug, self-impressed justice, a justice whose compassion is indistinguishable from hypocrisy. The story’s denoument has the cold inevitability of bleak downbeat masterpieces like Out of the Past or Rififi. Jim Aparo’s dynamic, offbeat visual storytelling in the last pages is like a series of punches to the jaw; a shot of Boston’s gun; Lilly shot in silhouette, so small she looks like she’s at the end of a tunnel; falling into Boston’s arms, a three-quarter shot of Brand as he realizes he’s fucked up, and then Deadman racing out of Richie’s body, while Batman stands down below, looking all dark and menacing and useless.

Maybe I’m missing something…but how does this not kick the shit out of The Killing Joke? Or Arkham Asylum? Or Dark Knight Returns? Or the Dark Knight movie? Or the Morrison Batman run? All that bloated, Jungian, Batman-As-Ur-Hero crap which is supposed to be so dark and serious and impressive… I mean, I like all that stuff, pretty much, but when you get right down to it, underneath all the sophisticated posturing — it’s pretty dumb isn’t it? You show me a writer propounding Batman as archetype, and I’ll show you an author engaging in serious adolescent bloviating. Batman as clueless, dickhead cop, on the other hand — that’s a bleak vision. Or a farce. Or both.

*********

Just a final short thought; the issue of intentionality came up in one of the earlier comments threads, and it’s been on my mind as I wrote this post too. Was Haney really trying to say something about oppression in the Metal Men team-up? Did he really have a bleak vision in the Deadman team-up? Isn’t he just trying to tell a goofy Batman story? Why saddle him with all this heavy crap? Why make him something he’s not?

Intentionality is always hard to figure, especially for someone like Haney, a scattershot, seat-of-the-pants writer, working in a form and at a time where there was little emphasis on personal vision or auteurishness. Even in that TCJ interview, there’s little discussion of themes or story intention; it’s all about the business end and who worked with who when. The interviewer never asks, “Well, why were you so interested in amnesia?” Or “Bob, what was your take on Batman as a character? Was he a kind of moral center in your work, or did you feel he was sometimes in the wrong? Or even, “What did you like specifically about the comics you wrote?”

Obviously, Haney isn’t an especially self-conscious writer. But unselfconscious isn’t the same as stupid. Shakespeare wasn’t especially self-conscious either, I’d argue. He was mostly about goofy plots, and fights, and blood, and putting stuff in his characters’ mouths which sounded cool. Still, in his own unsystematic, pulpy way, he managed to use his plays to think about things that were worth thinking about, and to say some stuff that was worth saying.

I’m not saying Haney is as good as Shakespeare, because I don’t think that he is. But he is plenty good enough to come up with some interesting things to say about politics in the Metal Men issue (as well as a few dumb things). He’s good enough to realize that Batman-as-paragon is often less interesting than Batman-as-dick. And he’s good enough to have written at least one perfect, sad, oddly elegant noir.

________

…and after two remarkable issues, #105 is just…eh. Batman teams with Wonder Woman, who’s in that phase where she decided to actually wear clothes rather than underwear and in retaliation her Gods punish her by taking away her powers. She still has a guardian angel though, who saves her from being roadkill on one occasion…good guardian angel! Guardian biscuits for you! Batman is a cad to a damsel in distress, but then he comes to his senses and helps her brother ship arms to revolutionaries in South America. Wonder how that went over with all of Batman’s buddies at the Pentagon, huh? At least we throw a few more “Bat-Hombre”s on the fire. And there’s always Jim Aparo, who draws a mean aged duenna.

______________

And hey, we’re done! Sort of. We’ve still got three more issues, which Tucker and I will co-blog in some fashion after Thanksgiving. Hope to see you then.

Update: And the first part of our race-to-the-finish co-blogging is here

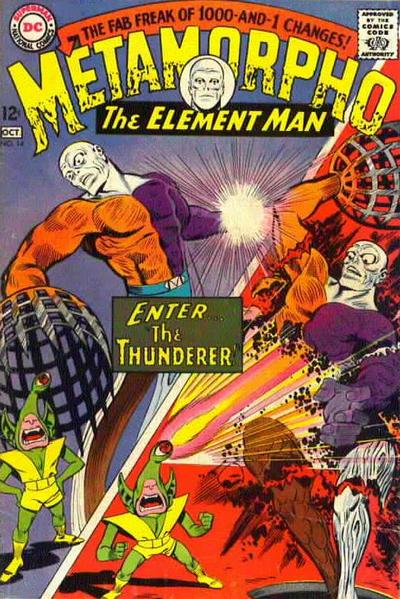

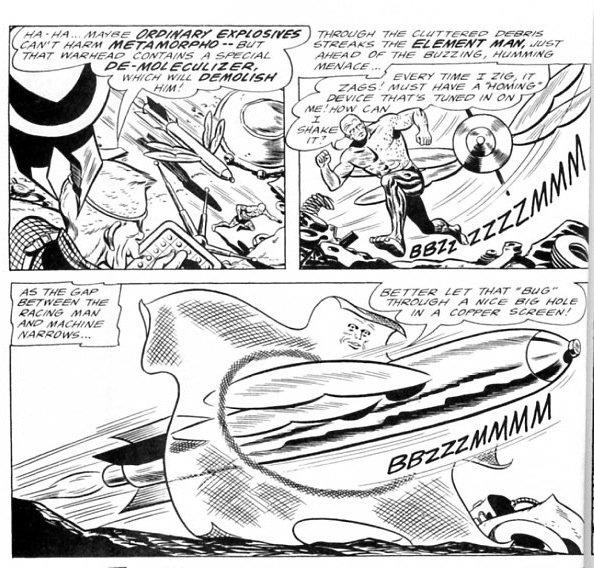

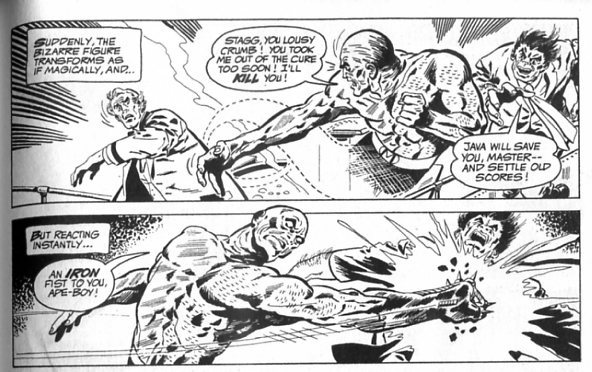

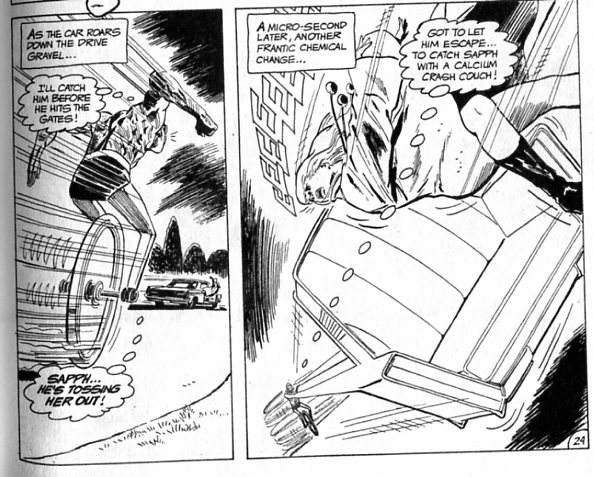

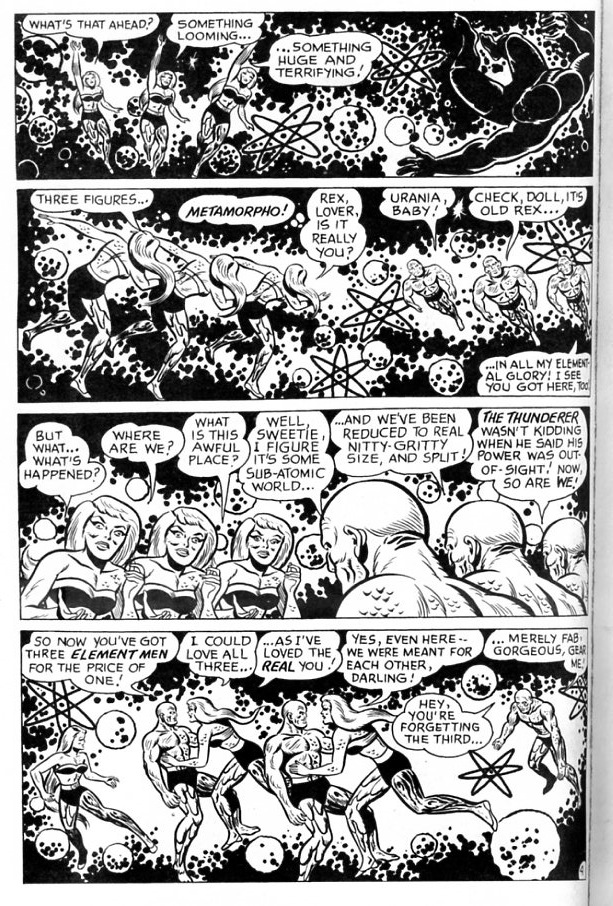

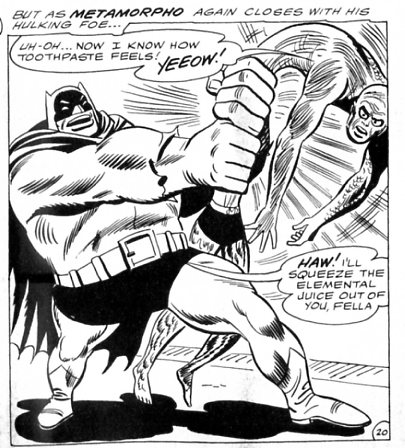

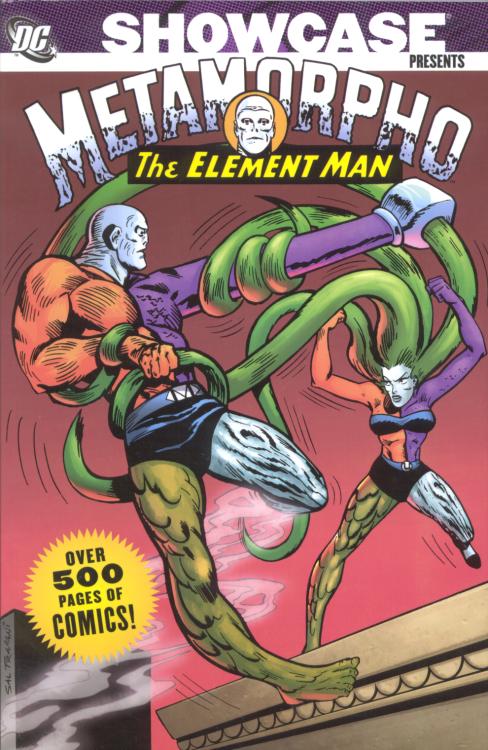

As I’ve said many a time before, I’m a big fan of the Bob Haney/Jim Aparo Brave and Bold. I’ve long been interested in reading Haney’s Metamorpho — it seemed like, if Haney was brilliant with other people’s characters, what would he do with his own? The hints I had seemed good; multi-colored shape shifting hero; bizarrely coiffed quasi-evil-scientist father-in-law; lovesick prehistoric frenemy; bombshell love interest. What’s not to like?

As I’ve said many a time before, I’m a big fan of the Bob Haney/Jim Aparo Brave and Bold. I’ve long been interested in reading Haney’s Metamorpho — it seemed like, if Haney was brilliant with other people’s characters, what would he do with his own? The hints I had seemed good; multi-colored shape shifting hero; bizarrely coiffed quasi-evil-scientist father-in-law; lovesick prehistoric frenemy; bombshell love interest. What’s not to like?