This piece contains spoilers, although I do not reveal the ending of the movie.

Some stories seem too smart to be symptomatic. Rather than try to suppress or exorcise the fraught, irrational elements that inevitably bubble up through the floorboards, some stories court the absurd directly. This instinct is the one truly smart thing about the movie Snowpiercer, the summer’s critical dark horse, recently released to a very positive reception on Netflix. The world’s audiences and film critics can be forgiven for projecting this intelligence upon the rest of the film, which doesn’t deserve it.

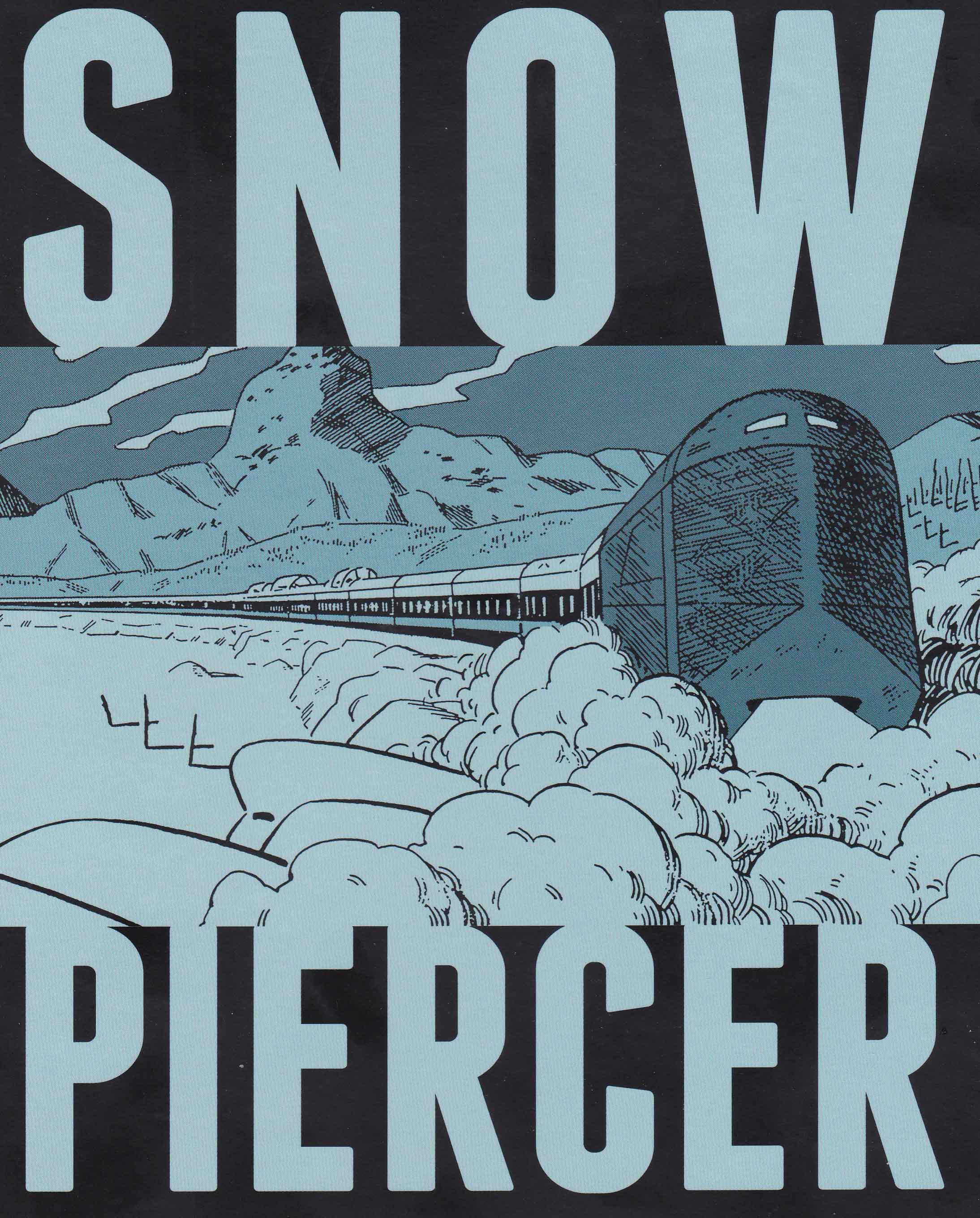

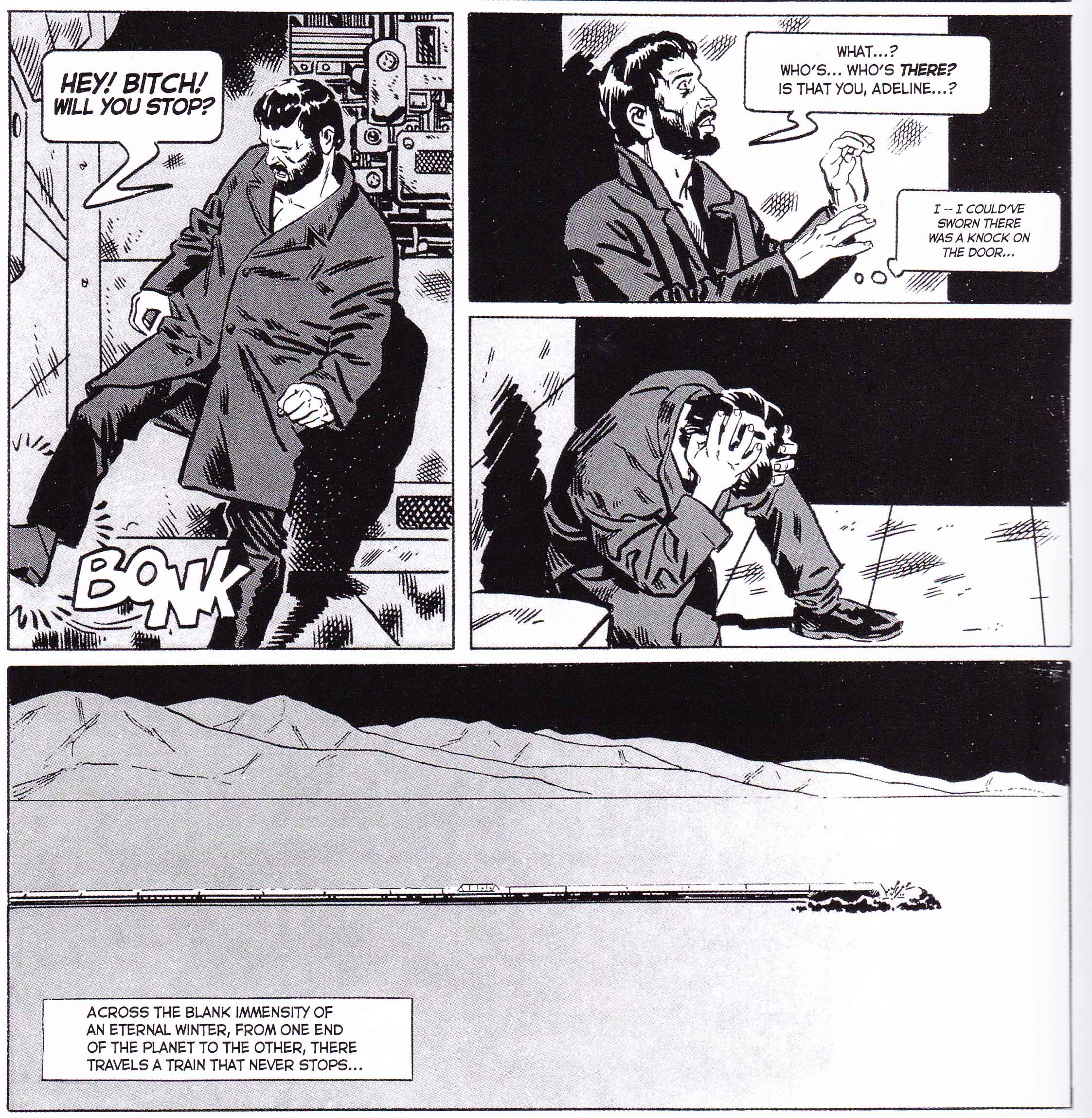

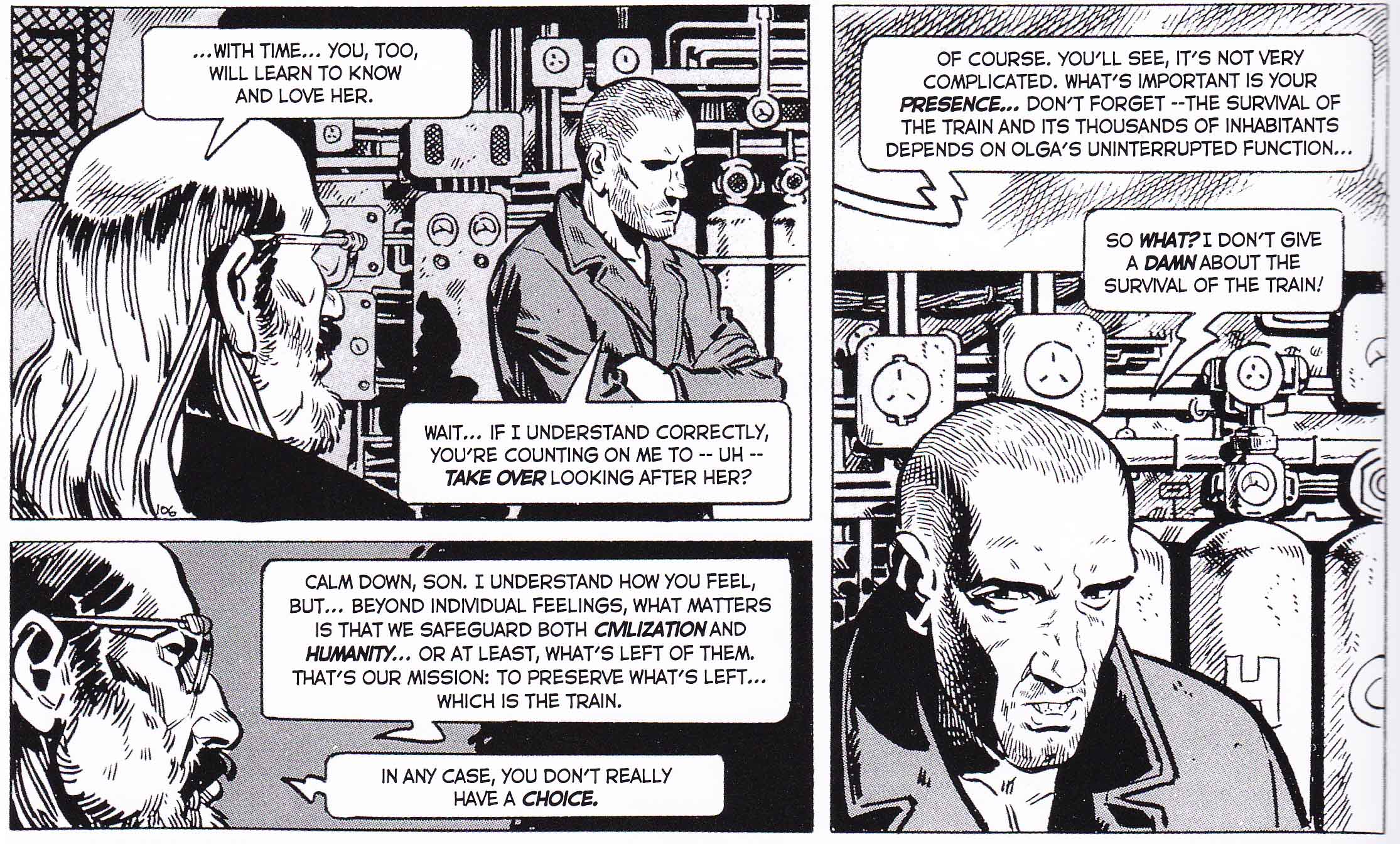

In Snowpiercer, the world’s governments attempt an easy-fix to climate change, releasing a cooling agent into the atmosphere. While this addresses an overly simplistic understanding of ‘global warming,’ (adding particles would enhance the greenhouse effect, if anything,) in the world of Snowpiercer, the cooling agents actually work. In fact, they completely freeze the Earth. The final survivors of humanity exist on a train, reputedly the only shelter designed to withstand the freezing temperatures outside. The train runs nonstop on a track that spans all of the Earth’s continents. Over the course of eighteen years, the original passenger assignments– first class, economy class and stowaways– become abstracted into a brutal caste system. The first class passengers live in a steampunk wonderland of galleria cars, beauty salons, mini mall arcades, swimming pools, greenhouses and aquariums. They worship the train’s inventor and unseen tyrant, Wilford, and the ‘immortal engine’ he tends. The economy passengers are barely seen (perhaps they’ve become the soldier class that oppresses the residents of the tail section?) The tail enders live in a windowless slum in the back, abused and barely subsisting on grotesque, gelatinous protein blocks. People are harvested for mysterious uses by the first class passengers, never to be seen in the tail again. The story follows the uprising of these passengers, who break through to the front of the train, witnessing the extravaganza car by car. Their forward movement mirrors a reel of film itself, the protagonists jumping from cell to cell, from set-piece to set-piece. Snowpiercer gets to have its cake and eat it too, decrying the excesses of the wealthy while relishing them. Along these lines, its allegories sound smart on paper, yet bamboozle more than they enlighten.

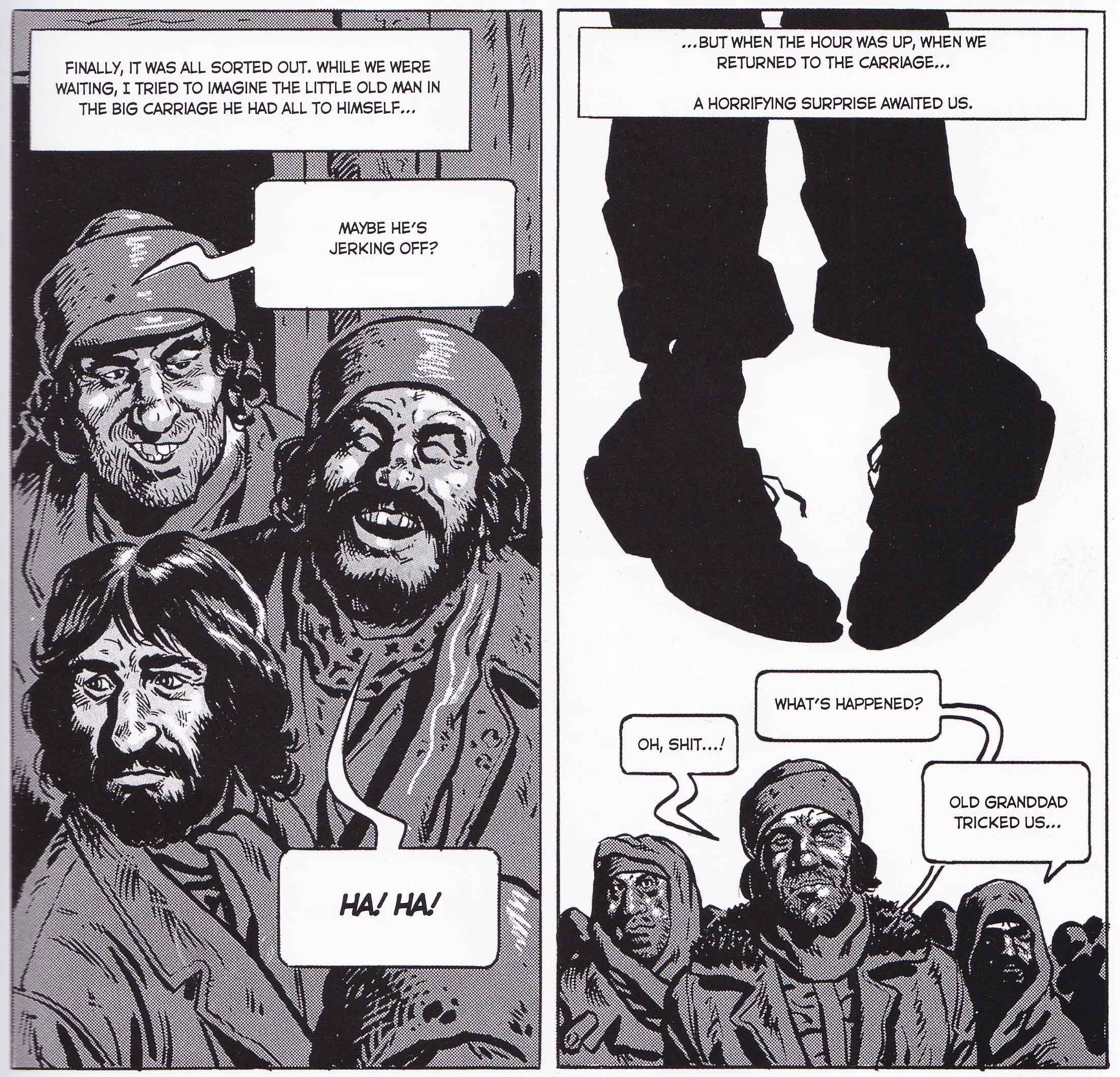

The fun of the film lies in its rigorous application of the rules of the childhood ‘hot lava’ game, where the threat of ‘instant death’ confines pretend-play to a bed or jungle gym, which can then be re-imagined into a self-sufficient world. It also borrows from the nightmarish joys of Juan José Arreola’s The Switchman, an absurdist satire of the Mexican rail system from 1952. The Switchman smartly excuses itself of having a plot, and revels in its own bizarro world-building. Snowpiercer would have been a better film if it had done the same, perhaps witnessing the train through the eyes of the kidnapped children or violinist, spirited away into the forbidden first-class cars, than from the vantage of the ambitious revolutionary who forces his way into them. Snowpiercer-the-film stems from Snowpiercer-the-comic, yes, but as Ng Suat Tong shows in his earlier essay, Curtis’ rebellion dramatically diverges from Proloff’s misanthropic death-drive, and the film’s uprising is a invention of the director, Bong Joon Ho. Bong follows the accepted Hollywood wisdom that an epic setting deserves an epic storyline, yet to prioritize the absurdity and delicious visuals, this storyline must be kept as a barebones as possible. In the words of Jones of the Jones boys, commenting on Suat’s piece, “The script’s role in an action movie is to get the hell out of the way, and stay there.” I’d argue that Snowpiercer is a rather sloppy, if inventive, action movie: the choreography is unclear, the chain of action and reactions extremely garbled. Its not the action that pushes the script out of the way, but the insistence on dreamlike spectacle. The point is not the axe-fight, but that everyone pauses to celebrate New Years in the middle of it.

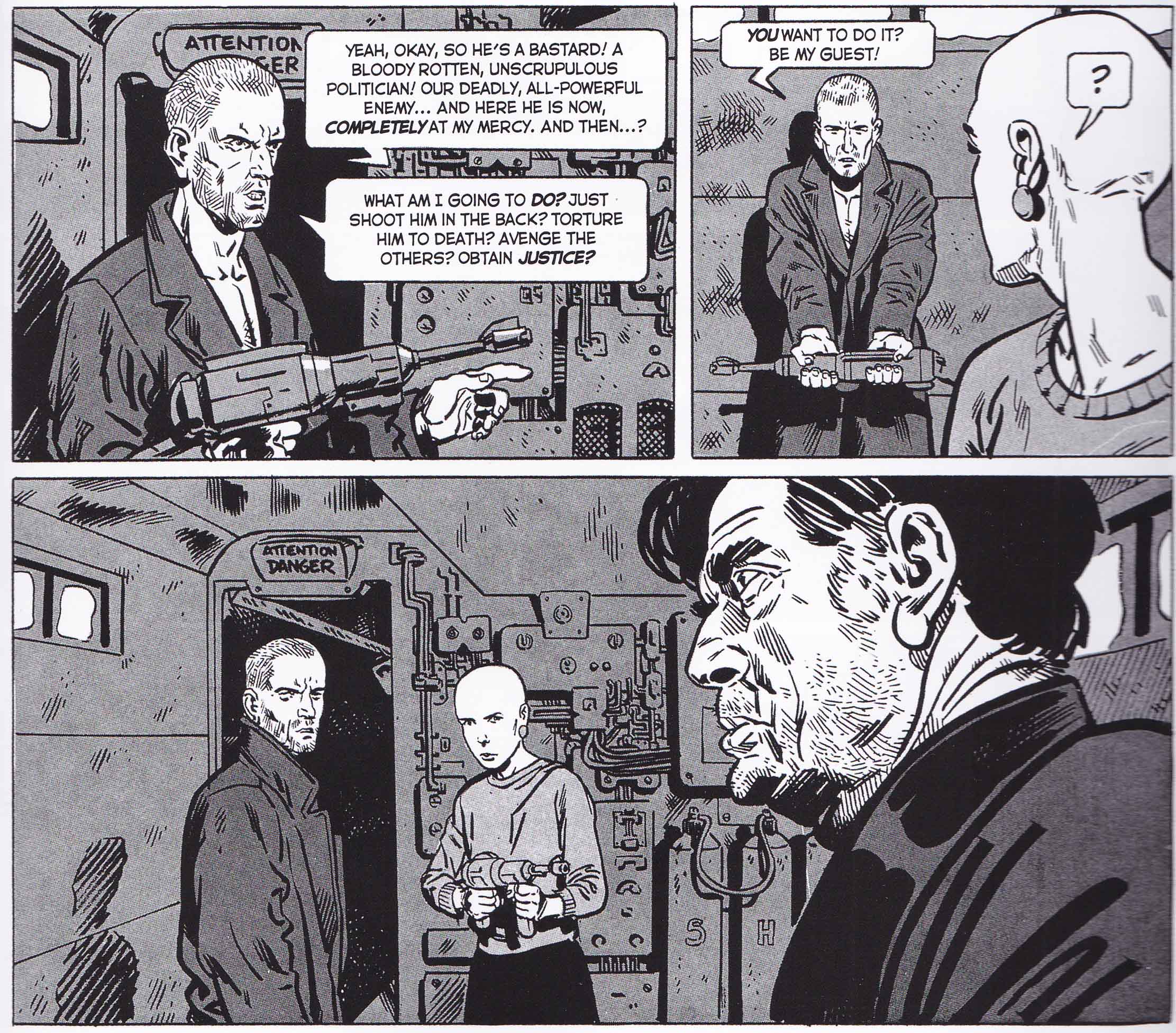

The characters rehash the most generic ‘motley band of heroes’ tropes. A bland, angst ridden woodsman named Curtis leads the revolt. Curtis is guided by Gilliam, aka Gandalf/Trotsky, the aged leader of the tail section, and followed around by an eager younger-brother figure, Edgar, who chiefly serves to open up giant plot holes. (He has an Irish accent and misses eating steak, yet is an orphan raised in the tail section from infancy.) Curtis’ plan relies on a enigmatic, manic Korean engineer, long imprisoned in a jail car, who tows along his doll-like and inexplicably psychic daughter, Yona, (essentially River from Firefly.)* The engineer knows how to open the doors between cars, but must be bribed with drugs. We’ve got a gutsy black mother, and a mute, ethnic, martial arts kid. Bong likely suspected that these empty shells couldn’t generate much emotional investment on their own, so he falls back on trite parent-and-child melodrama. Cue the wistful soliloquys of grown-up orphans, and the desperate plight of the parents of the kidnapped children.

When Curtis finally reaches Wilford in the final car, the inventor breaks and tempts him with a bland, 50s caricature of fatherhood, calling Curtis “My boy,” and promising to make Curtis heir to his hallowed position. This exchange contains the pessimistic, political twist so critically beloved. Gilliam and Wilford turn out to be co-conspirators, encouraging tail-end rebellions so as to ‘decrease the surplus population.’ This twist, and its corresponding political allegory, seems to be the one time where Bong really cares about the storyline, (it is his invention, after all.) Bong even leads the audience away from this suspicion early on, when Gilliam requests Wilford’s minister to relay the message that he and Wilford “need to talk.” Wilford’s sneering, flippant report of his and Gilliam’s intimacy, especially considering the inhumane conditions Gilliam suffered as part of the tail class, undermines the reveal. Wilford must still be lying on some level, as Bong never connects why Gilliam would endure what he did, and care for the tail enders as he did, under such false pretenses. It’s a twist alright, crossed off the list of what a good action movie plot should accomplish, but one that’s hardly believable. It counts as political allegory, but one deeply out of touch with its own humanity.

The character’s motivations and the political allegory must be dropped whenever they threaten to overshadow the dream-logic and dream-visuals themselves. For example, the tail-section people talk a lot about food, a basic necessity of which they are almost deprived. The revelation that their protein blocks are made of bugs is mined for horror, and ‘steak’ becomes a running symbol. When they first make it into the vacated economy class cars, a rebel protests that the residents had abandoned their food “on the table.” Most horrifically, Curtis confesses that in the first month onboard the Snowpiercer, the stowaways came so close to starving that they resorted to predatorily cannibalism– not just eating deceased humans, but hunting each other for food. Hunger, and outrage over hunger, is a useful and efficient way to flesh out these characters as oppressed and desperate people. Yet, this essential motivation must be dropped where it distracts from the film’s absurdist agenda. After sustaining massive losses of their people in battle, a small group of rebels finally makes it into the first-class section, and into a marvelous aquarium. At the end of the aquarium sits a sushi bar. The rebels sit down and begin to have sushi, which is prepared by a man in African dress. There’s no griping about the elitist luxury, the wait, the small portions. Tanya, the black woman, makes a quick jibe about their not being enough fish to have sushi all the time, but there’s no urgency in their hunger, or even to keep moving ahead. This is one of the strongest sequences of the film, where the dream logic completely dominates the action, and the disposability of the storytelling becomes most transparent. Its easy to miss Minister Mason’s explanation of the aquarium as a closed ecosystem, “where the number of individual units must be closely, precisely, controlled,” later reprised by Wilford in half-explaining why certain amounts of tail end people must be periodically slaughtered.

Deliberate absurdity, particularly in high budget films, communicates a kind of intelligence. The director and crew are “in” on the artificiality, the fictionality, the letter-box. They enjoy interrupting the audience members, who are busy putting together the pieces to understand what’s going on. Audiences enjoy these interruptions because they are surprising, and because it connects the audience and author, who can “secretly” recognize each other. (As long as the audience privileges aesthetic distance over emotional absorption in a film, something that is statistically more prevalent with the wealthy, and consciously resisted in working class audiences. Pierre Bourdieu covers this phenomena in his book, Distinction.) While absurdity, irrationality, and surreality are present in popular culture, they debuted as high brow developments in art and literature, and still carry a kind of ‘legitimizing’ earmark. “This action movie is smart, because it is so dream-like,” for example.

Frank Kermode, a scholar devoted to reading between the lines of popular and religious texts, finds high-brow literature to be less rife for analysis because of its intentional irrationality. ‘Weirdness’ arrives in the strictly popular text by accident, seeping through routine hackwork and cliché, and exposing period or authorial concerns. This weirdness often comes in the form of repetition and/or fetishization of inessential details or descriptions, or of strange sequences that have nothing to do with the plot, (called BLAMs on TV Tropes.) High-brow authors deliberately insert weirdness, largely to avert or disrupt literary formulas. Kermode writes that in high-brow literature, “there is much more material that is less manifestly under the control of authority, less easily subordinated to ‘clearness and effect’ more palpably the enemy of order, of interpretative consensus, of message.”

Bong repeatedly prioritizes surreality and effect over message and order in Snowpiercer, positioning it in Kermode’s reasoning as a high-brow text intended to be appreciated from a critical distance, (but still enjoyed for its tittilating battle scenes.) Yet Snowpiercer is not without its symptomatic fixations. Notably, it betrays a fascination with amputation. Just before Curtis meets Wilford, he confesses that the tail-enders initially cannibalized each other to survive, and he hates himself because he knows “that babies taste best.” Curtis killed a woman for a baby, but before he could eat it, he was stopped by Gilliam, who cut off his arm for Curtis to eat instead. “And then one by one, other people in the tail section started cutting off arms and legs and offering them. It was like a miracle. And I wanted to. I tried, it’s… A month later, Wilford’s soldiers brought those protein blocks. We’ve been eatin’ that shit ever since.”

Snowpiercer purports that the tail section became a kind of dystopic utopia, a situation so horrible it brought out ultimate selflessness. Gilliam’s response is the Eucharist made real, and was not only presumably repeated with his leg, but by a whole assembly of amputated elders, who limp notably in the film’s present on crutches. When Gilliam appoints Curtis as his successor, Curtis struggles, replying, “How can I lead if I have two good arms?” Gilliam then reveals the scar from when Curtis ‘tried.’ Curtis’ character arc isn’t completed until he loses his arm between the gears of the engine, in order to rescue a kidnapped child. As if released from his earthly limitations, he then instinctively sacrifices themselves to save Yona and the child from a fiery explosion.

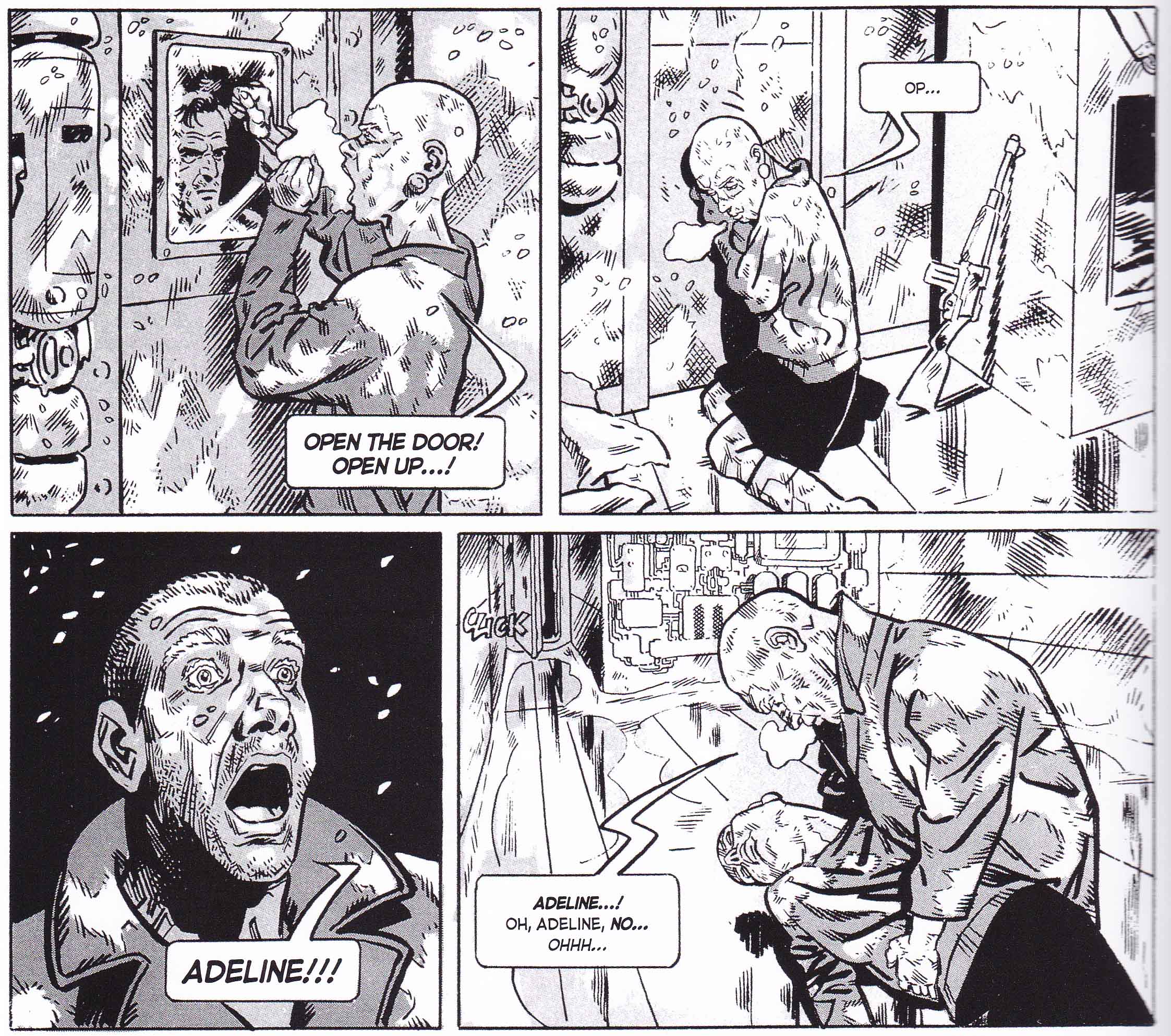

The obsession with amputation is not limited to Curtis’ realization. When two children are kidnapped at the outset, a father lurches out in rage and throws his shoe at an elite. In punishment, his arm is shoved outside of the train for seven minutes, and then pulverized by a sledgehammer. In the opening scenes of the film, an old man is also abducted by soldiers to play violin for the first class. At first he volunteers, thinking that he and his wife, another violinist, will both be able to go. A soldier demands, “Show me your hands… you follow me. Leave your belongings. We just need your hands.” The man, realizing he must go without his wife, asks, “Not both?” The soldier sneers, “Yes, both hands.” When the man resists, the soldiers respond by knocking the woman unconscious, and crushing her exposed hand underfoot.

The lower classes have long been equated with their hands and manual labor. Its worth noting that the children are kidnapped because they are small enough to fit inside the train engine and remove grease by hand. According to Bourdieu’s ethnography of France in the 1960s, Distinction, this symbolism is understood at all levels of society, but, “At higher levels in the social hierarchy, the remarks become increasingly abstract, with (other people’s) hands, labour and old age functioning as allegories or symbols which serve as pretexts for general reflections on general problems.” When shown a picture of an old woman’s gnarled hands, working class respondents tended to respond to the picture intimately albeit conventionally, considering and personifying the photographed person, and the work she did. The middle class respondents are the first to routinely overlay ethical virtues and aesthetic comparisons onto this, and the highest classes tend to ‘amputate’ the woman entirely, with responses like “‘These two hands unquestionable evoke a poor and unhappy old age.’ (teacher, provinces.)” The upper classes also have a tendency to make highly aestheticizing references, such as in this representative remark from an engineer in Paris: “I find this a very beautiful photograph. Its the very symbol of toil. It puts me in mind of Flaubert’s old servant-woman… That woman’s gesture, at once very humble… It’s terrible that work and poverty are so deforming.” Its worth noting that Bourdieu’s class system is based more on educational level and inherited capital than earned capital, as these are not tendencies based as much on wealth as on the ability (both learned and afforded) to live abstractly.

Conflating the labor class with hands is so established that it can be found within Wikipedia’s basic definition of ‘synecdoche.’ This synecdoche also consists of the message and opening epigram of Metropolis, perhaps the most canonical caste-system dystopic film, when it says, “There can be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator.” Snowpiercer reiterates this in a baser, more pessimistic form, in the Minister’s speech during a torture demonstration:

“Would you wear a shoe on your head? Of course you wouldn’t wear a shoe on your head. A shoe doesn’t belong on your head. A shoe belongs on your foot. A hat belongs on your head. I am a hat, you are a shoe. I belong on the head, you belong on the foot. Yes? So it is. In the beginning, order was prescribed by your ticket. First class, economy, and free-loaders, like you … Each in its own particular, preordained position. So it is. Now, as in the beginning, I belong to the front. You belong to the tail. When the foot seeks the place of the head, a sacred line is crossed. Know your place. Be your place. Be a shoe.”

If Bong were simply interested in amputations, visually or conceptually, they might appear more frequently in the graphic battle scenes. Instead, they are explicitly connected to anxieties about the tail end people, particularly in their functioning either as leaders or workers. Also, while the amputations discussed or shown on-screen almost exclusively pertain to arms and hands, Snowpiercer alters the standard synecdoche, assigning the base class to feet. More than that, the relationship of the elite and lower classes is further abstracted to clothing from anatomy, as if the parts of humanity no longer constituted the body of humankind, but served a greater reality that could exist without them. In Snowpiercer, a train’s engine is abstracted into a god, and the caste system into a holy order. Perhaps the greater reality is the train, which people serve but do not constitute. Perhaps it is abstracted Order itself.

In Snowpiercer, the lowest class is no longer a labor class. That may provide one answer to these questions. Hands work. Unlike Metropolis, or the grand body of film dystopias that followed, the tail enders are not shown toiling in factories or industrial wastelands. They are explicitly a welfare class. Only the kidnapped children have jobs maintaining the train, but they are slaves, and the one mentioned janitor died seventeen years ago. The tail enders did not have a fare when they boarded, and by the accepted logic of train travel, can be kicked off at any time. The fact that they aren’t is then an act of charity. The fact that the elites manufacture and provide them with food and water becomes an act of charity.

The tail enders can decry the insanity of prejudice and poverty in a post apocalyptic world, but the problem is, reality has been replaced with an insane, man-made system where economic class is not arbitrary. The rebels rarely appeal to concepts of ‘justice,’ or ‘human rights.’ They know their treatment is despicable, but their ability to express why, or imagine an alternative social order, has shrunk with their horizons. The tail enders never ask a question that Bong never has to answer– what more is demanded of Wilford and the elite passengers, who have ‘legitimate’ passage on this train? As long as they keep the tail-enders alive, they could be said to do more than enough. The protection of ‘a closed ecosystem’ where the stowaways are essentially parasites, make horrific, horrible sense. By avoiding the consequences of this logic, Bong made a movie that only falsely champions the human spirit. In truth, Snowpiercer participates in the same conservative media effort to reconfigure the ‘labor class’ into a ‘welfare class,’ and redefining social services into ‘entitlements.’

On a gut level, Bong may be uneasy with the severing of labor from the ‘labor class,’ although I won’t try to assume the level of his involvement or awareness of American politics or journalism. Amputation is a violent and disturbing image, and Bong does not shy away from its horror. It’s a fitting symbol, especially considering that conservative pundits sever labor from the labor class to drum up support and engagement from their political base, at the expense of real lives. Propoganda is entertainment. When Wilford discusses his perspective of the uprisings, he judges them based on their entertainment value, and the value of entertainment in quieting the masses. He says to Curtis, “We need to maintain a proper balance of anxiety and fear, chaos and horror, in order to keep life going. And if we don’t have that, we need to invent it. In that sense, the Great Curtis Revolution you invented was truly a masterpiece.” A military class seems like an unnecessary expense, unless it’s to give the paying passengers a living video game. All the first class passengers do is entertain themselves. The satire isn’t toothless, and the victimized tail-end have real-life counterparts in the working class. Still, the question stands– the logic that the tail-enders are parasites is never confronted, and thus never rebutted. The film envisions social service as dehumanizing, and the idleness of the base class as a given in an entertainment-based society. A labor-less lower class is the one great absurdity left unexplored. Violent entertainment may be an opiate, but the film itself is complicit in it. Which is fitting for a high-brow treatment of an indulgent action premise, which sidelines the struggles of oppressed people for frivolous absurdities.