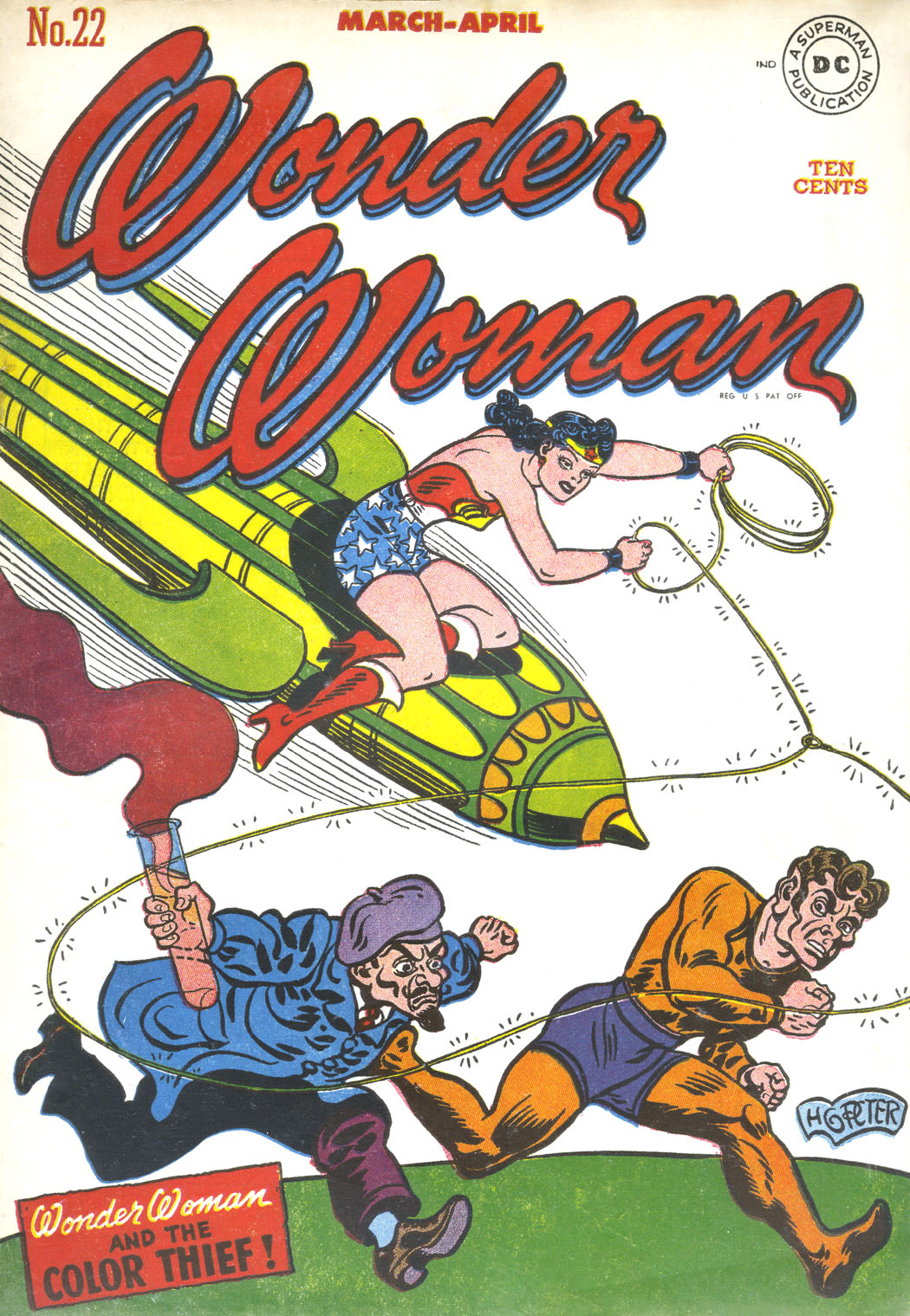

Wonder Woman #22 was probably the worst one of Marston/Peter’s run…so bad, in fact, that I wondered whether significant parts of it might not have been ghosted.

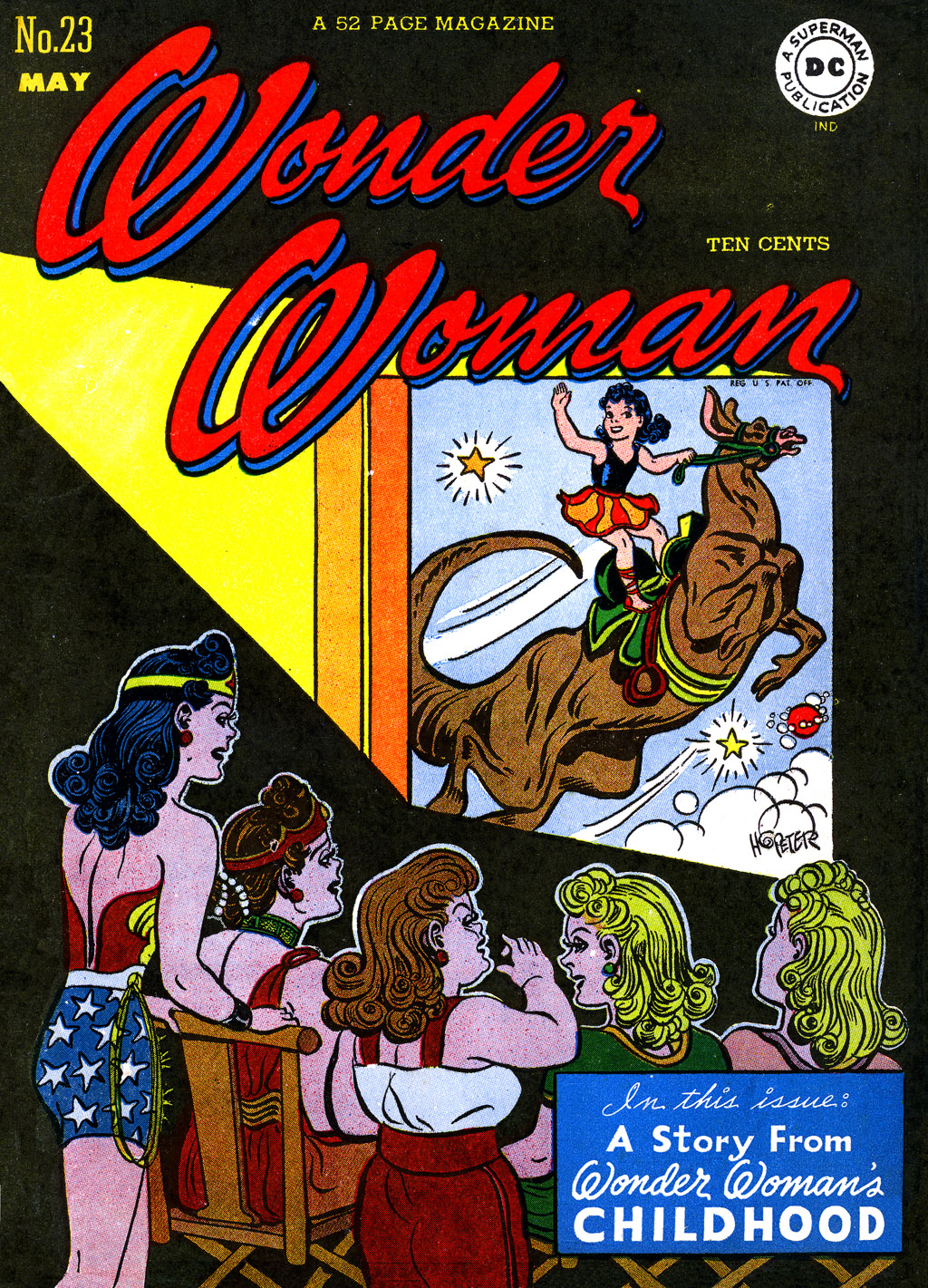

Issue #23 is much better. It’s not one of the series high points — and notably, like 22, it has three short stories rather than one long epic, a change which I presume must be related to Marston’s sickness (he actually died of cancer in May 1947, which is this issue’s cover date.) Still, whether Marston was writing shorter stories on his death bed, or whether these are leftover scripts that he had lying about unpublished (and they can’t be too old, because they’re post-war) the result is perfectly acceptable, if not great.

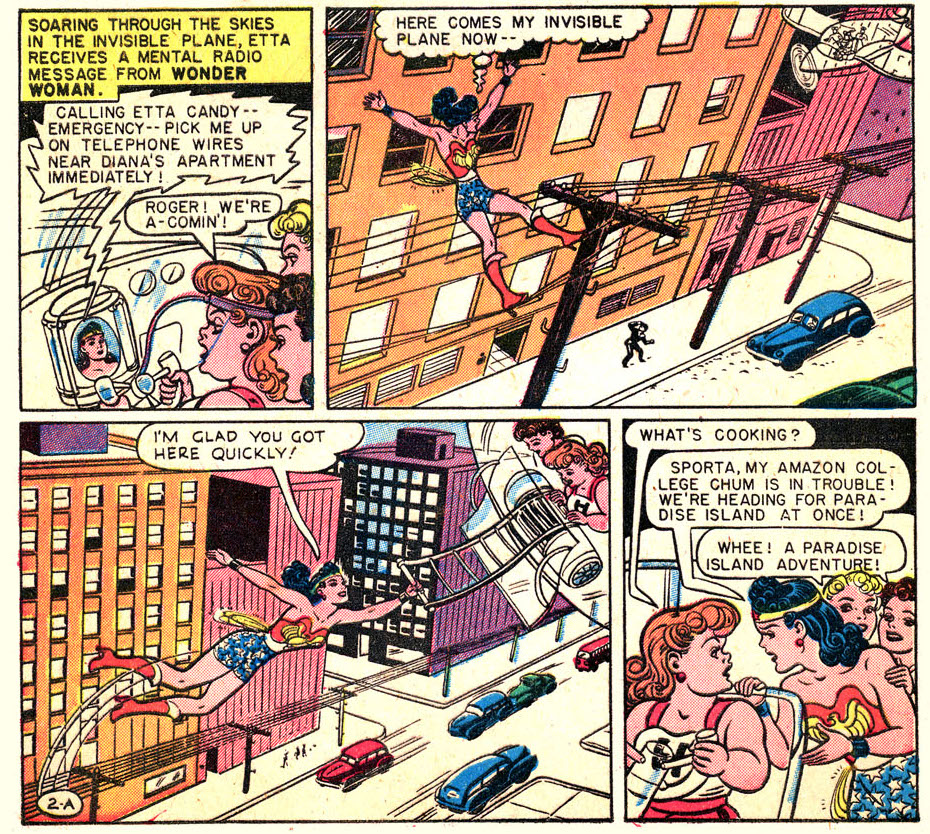

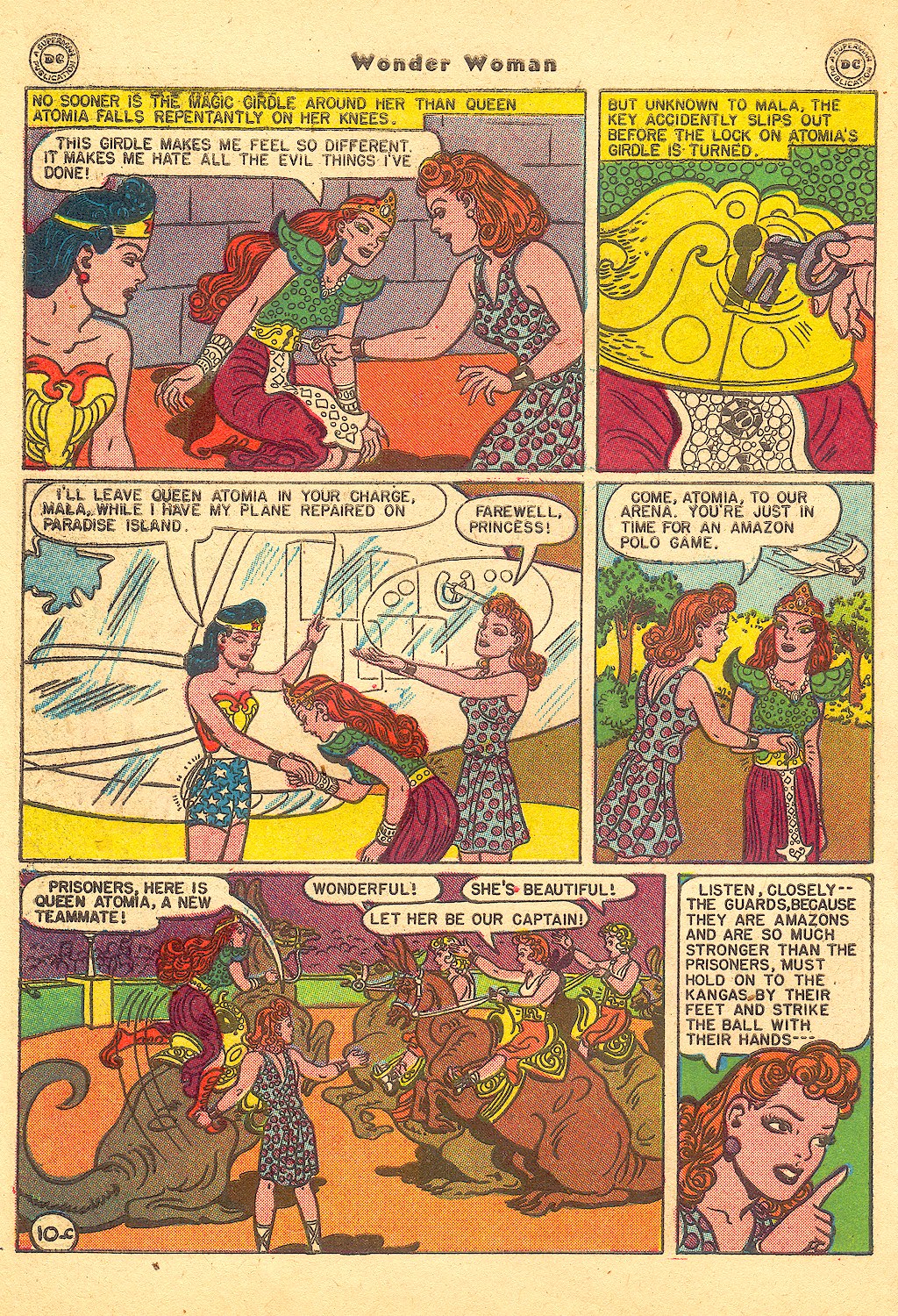

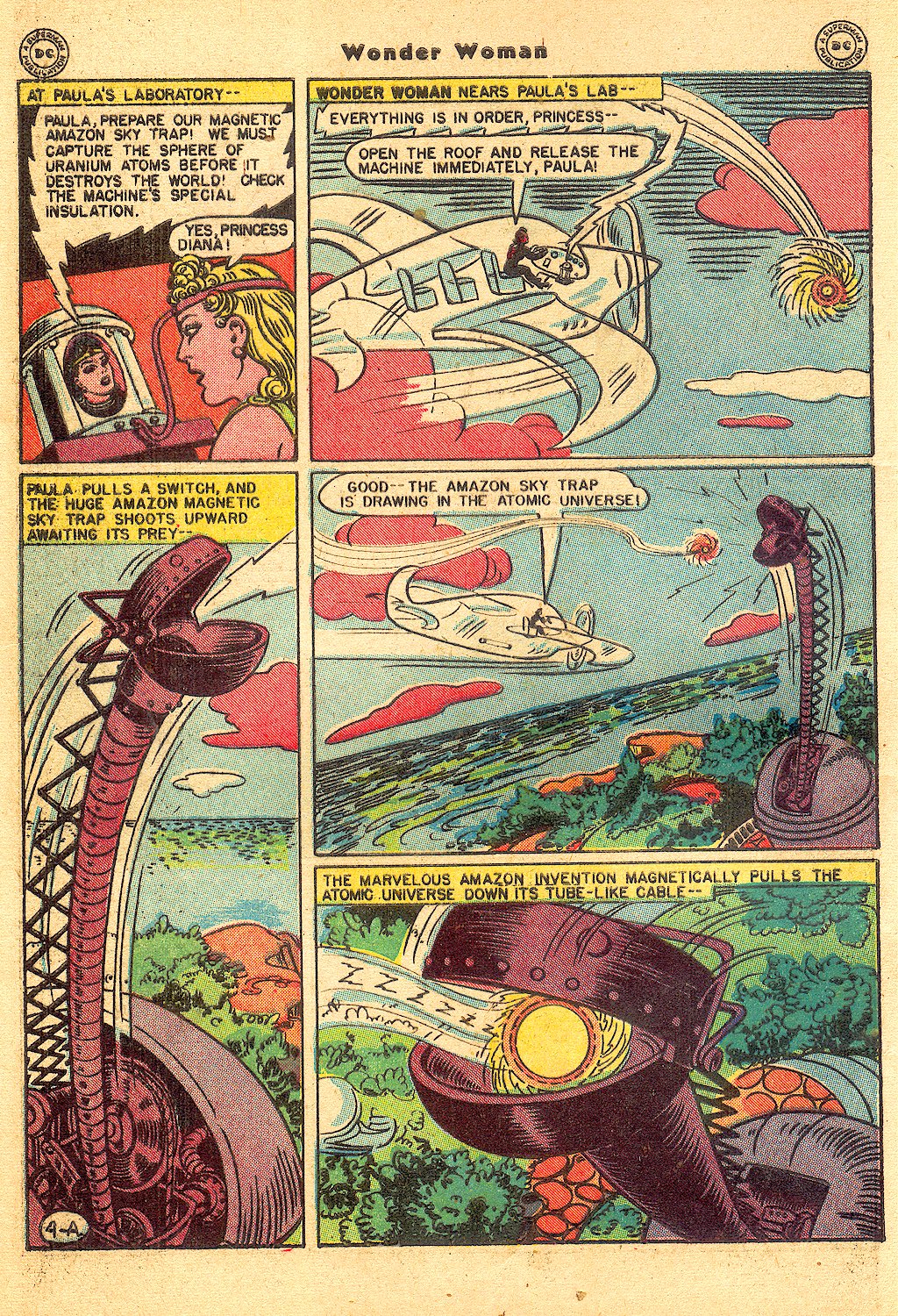

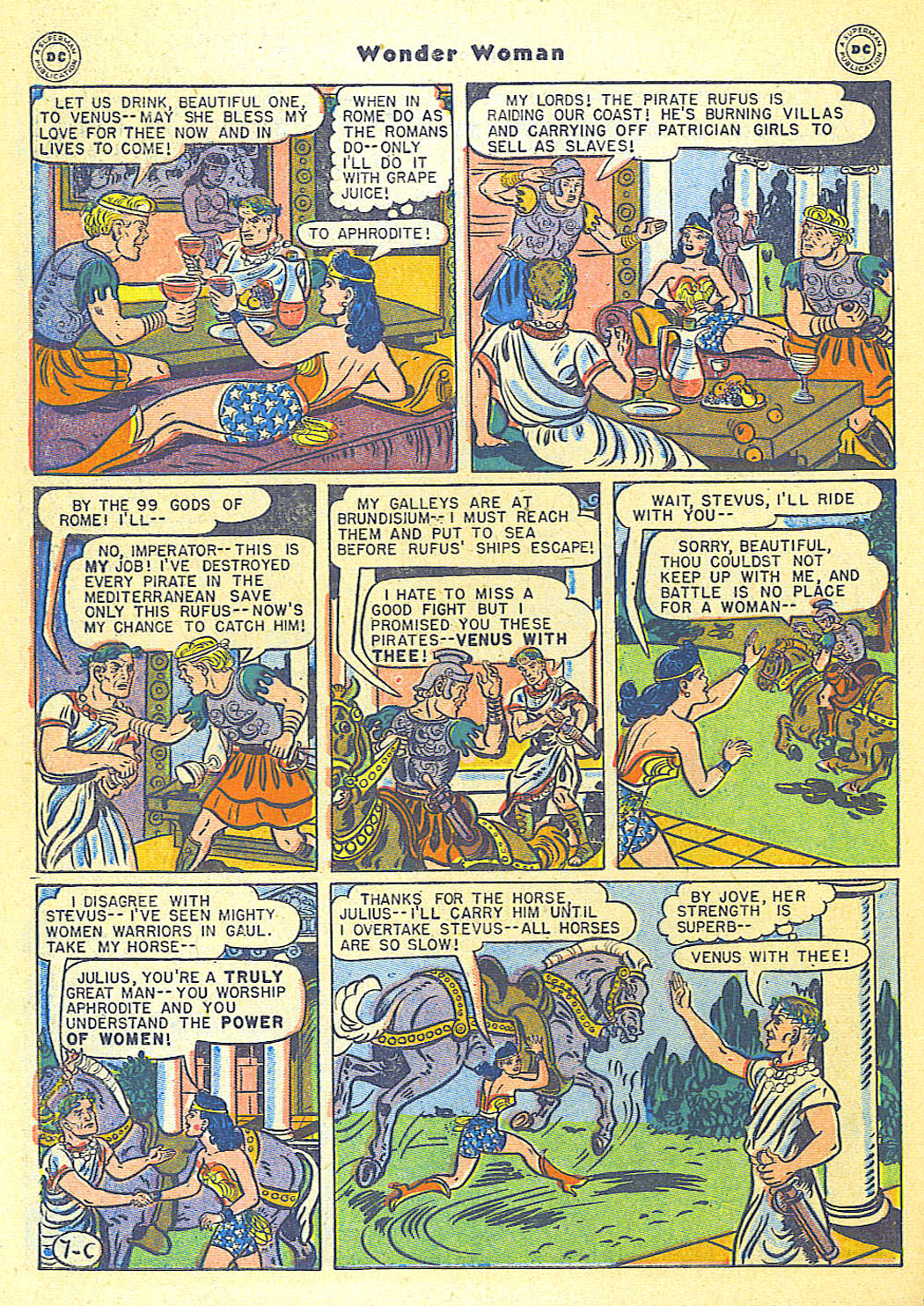

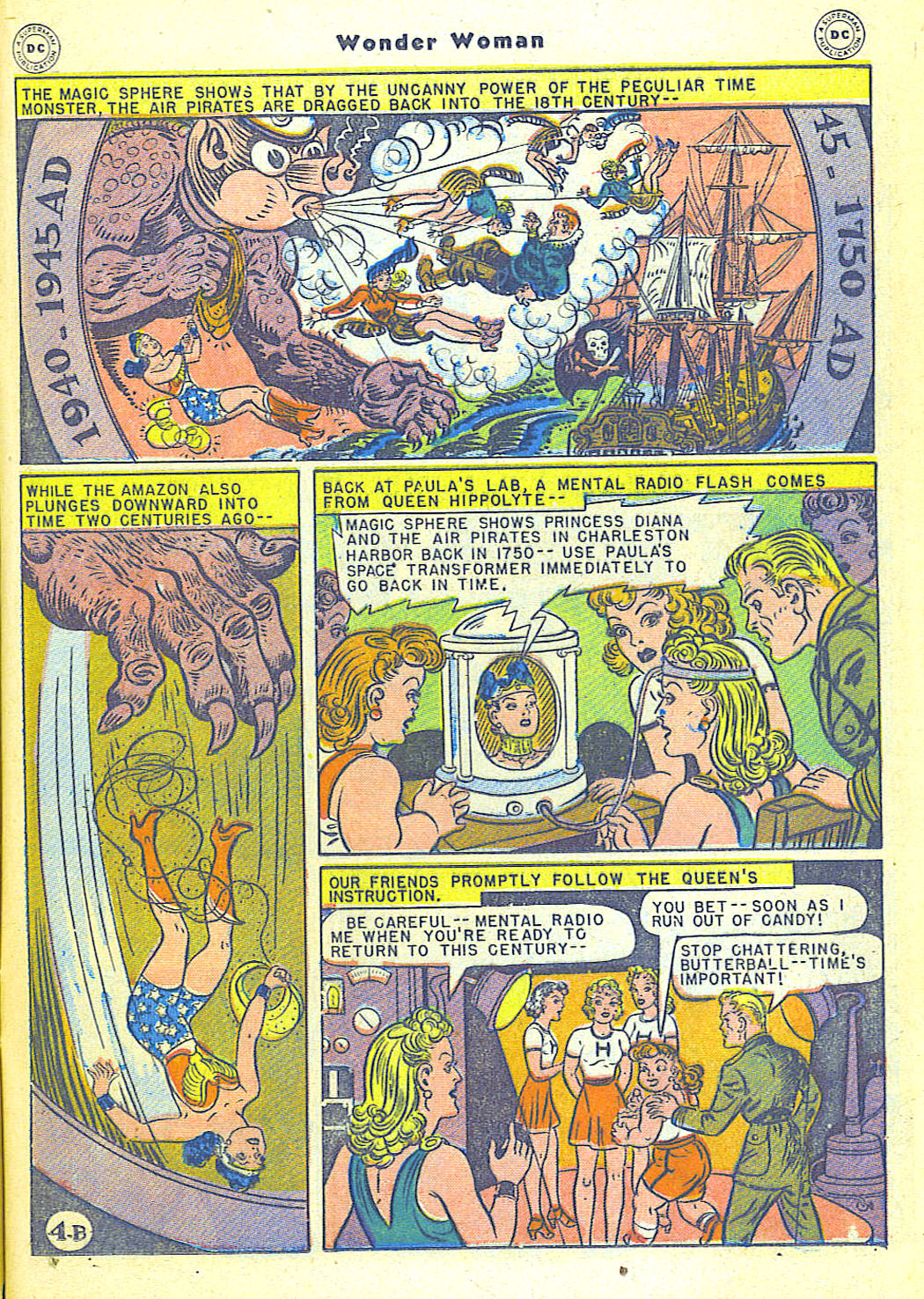

As the Holiday girl there in the lower right indicates, the first story is a paradise island adventure. All the more welcome since Harry Peter seems to be in fine form; that picture of WW sitting on the telephone wires waiting for her robot plane with the buildings slanting down vertiginously in the background is pretty fantastic.

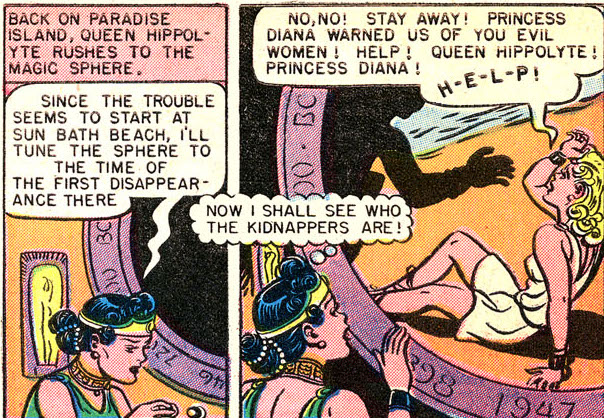

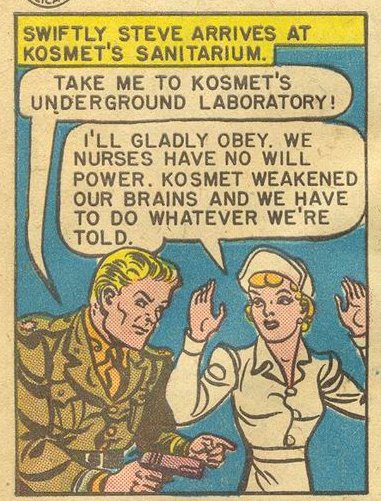

Anyway in this story Amazons are disappearing from paradise island’s beach. This gives Hippolyta a chance to watch as her viewfinder presents her with a Perils of Pauline moment:

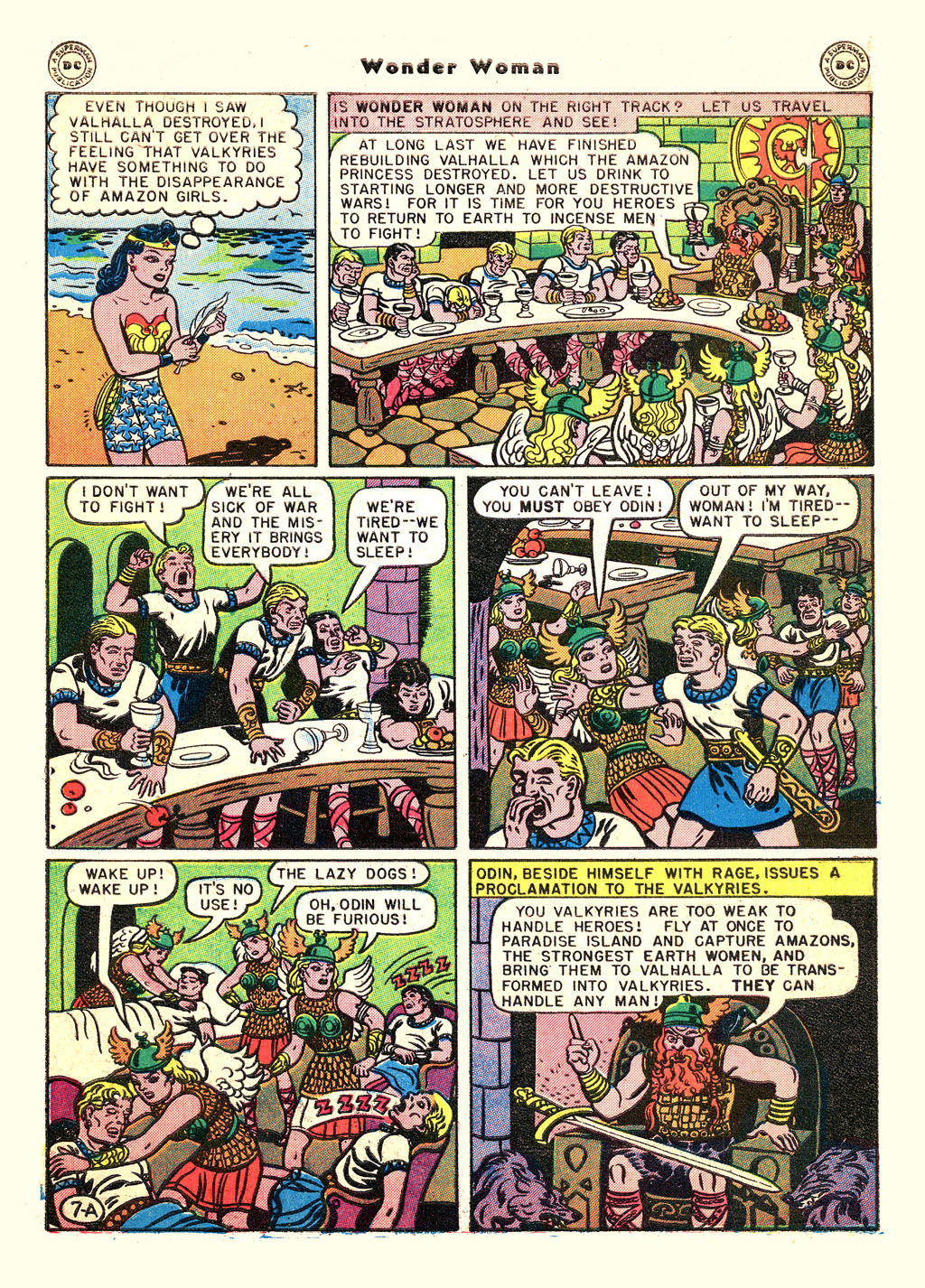

Anyway, the viewfinder breaks inopportunely, shattered by a bolt from Odin, whose Valkyries are flying down to Paradise Island to kidnap Amazons. Why you ask? Well….

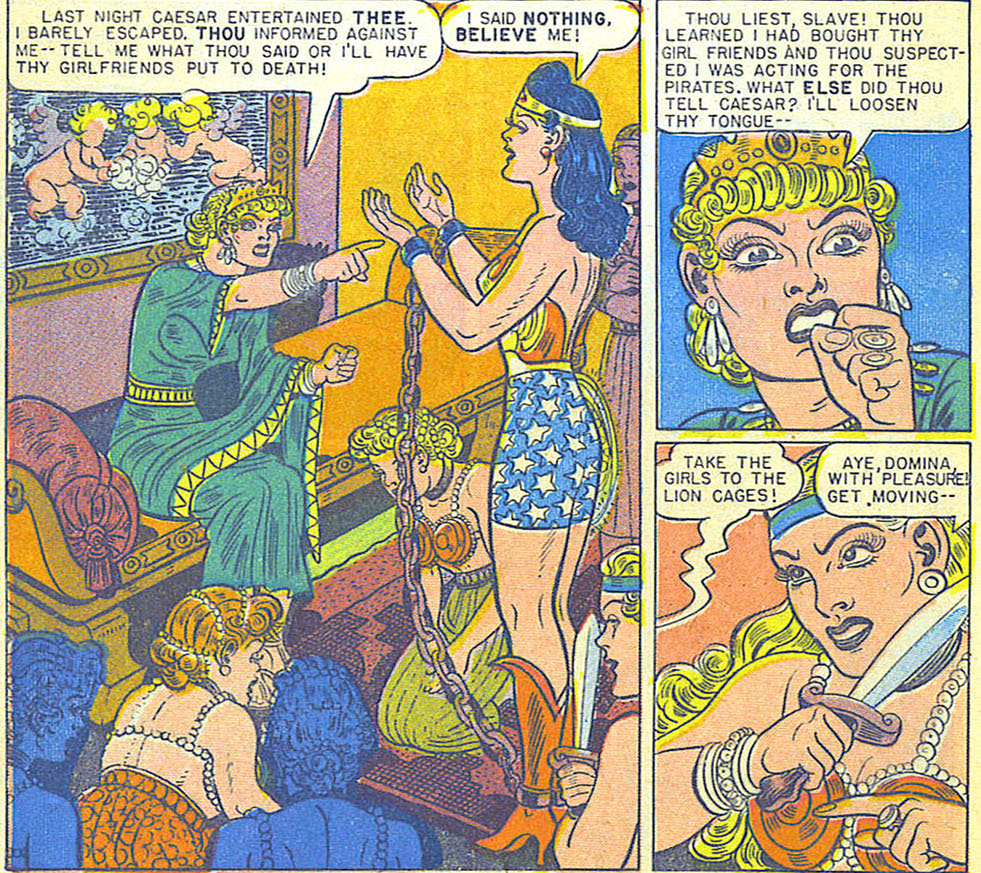

Odin has captured heroes (i.e. veterans) and wants them to go to earth to incense others to fight. But the heroes are tuckered out; all they want to do is sleep. Since his Valkyries can’t get the men to fight, Odin tells them to kidnap Amazons so *they* can get the heroes to go to war again.

As usual with Marston, the gender politics are delightfully convoluted. Obviously, the main instigator of warfare is the sadistic male patriarch, Odin. But the male “heroes” are shown throughout as being soft, manipulable, and not especially violent — they need a strong female hand if they’re going to be effective fighters. So in some sense it’s really women who are the embodiment of military virtues.

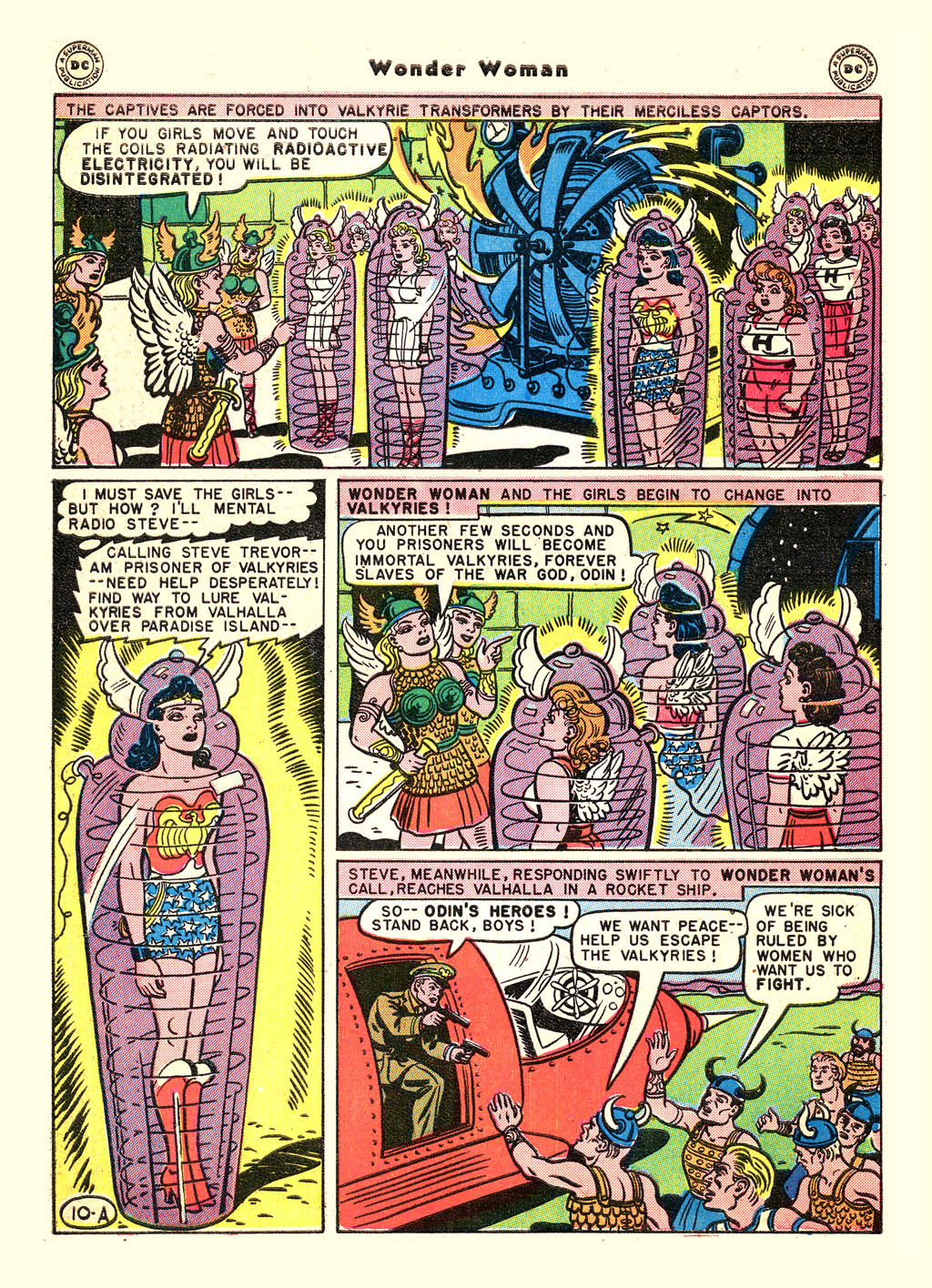

The funniest panel here is the bottom one, where the male heroes claim to be sick of being ruled by women “who want us to fight” — the implication being that they’re perfectly happy to be ruled by women who don’t want them to fight.

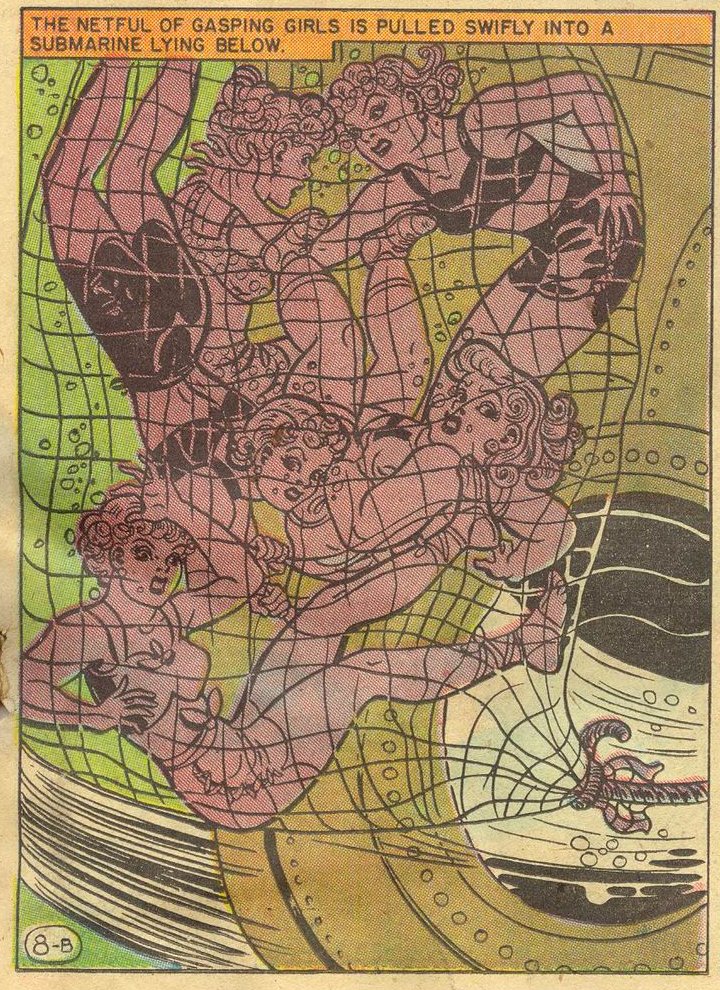

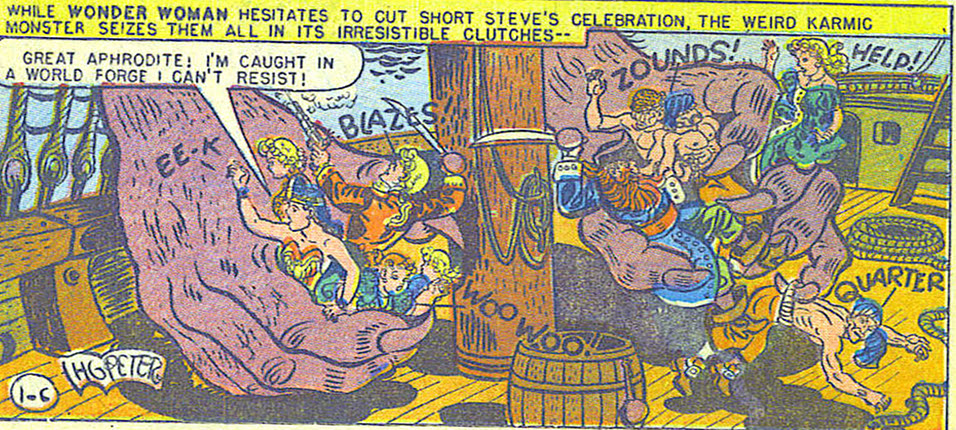

The rest of the page is interesting as well, though; the Valkyries have encased WW and Amazons and Holiday Girls in energy to trap them and turn them into Valkyries themselves. The purple energy happens in this case to look like the outline of Russian dolls…and of course, standing stock still in their various outfits, the transforming women look more than a little like dolls themselves (with special wing attachments!) I talked about the connection between Wonder Woman and doll stories before. In this case, the Valkyries eroticized dominance/appreciation of the Amazons is both about enjoying femininity *and* enjoying martial virtues. In fact, there’s barely an *and* there; for Marston, the more effectively militant you are, the more feminine you are (at least if you’re a woman.)

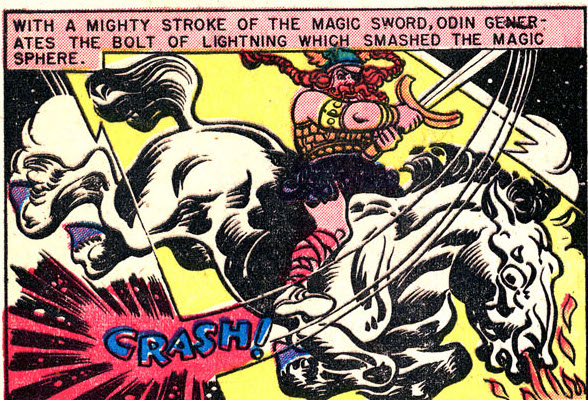

Which is why, in the middle right pane abovel, Aphrodite emphasizes that WW and the Holiday Girls are “courageous, loving girls” — the point being that courage and loving femininity go together. The natural conclusion is shown in the bottom left panel, where Odin, the supposed wargod, just gives up and offs himself (throwing down his phallic sword) when WW robs him of his Valkyries.

That page is pretty great in other ways as well, with winged Holiday girls and winged Amazons flying about with sky kangas and that magnificently phallic spaceship that Steve is piloting. I especially like the way the spaceship in the upper left panel mirrors the motion of the sky kanga in the upper right — as if the ubermaleness is just an image of, or subsumed within, the undulating sea of femininity. Maleness seems part of the harmonious whole of femininity rather than an opposition to it.

I also love that middle left panel; the scribbly sky-kangas and the valkyries being tied up here and tied up there, with scale all off-kilter so everybody looks like paper doll cutouts. This is definitely one of Peter’s most Henry Darger moments.

And as long as I’m gushing about Peter — check out this horse.

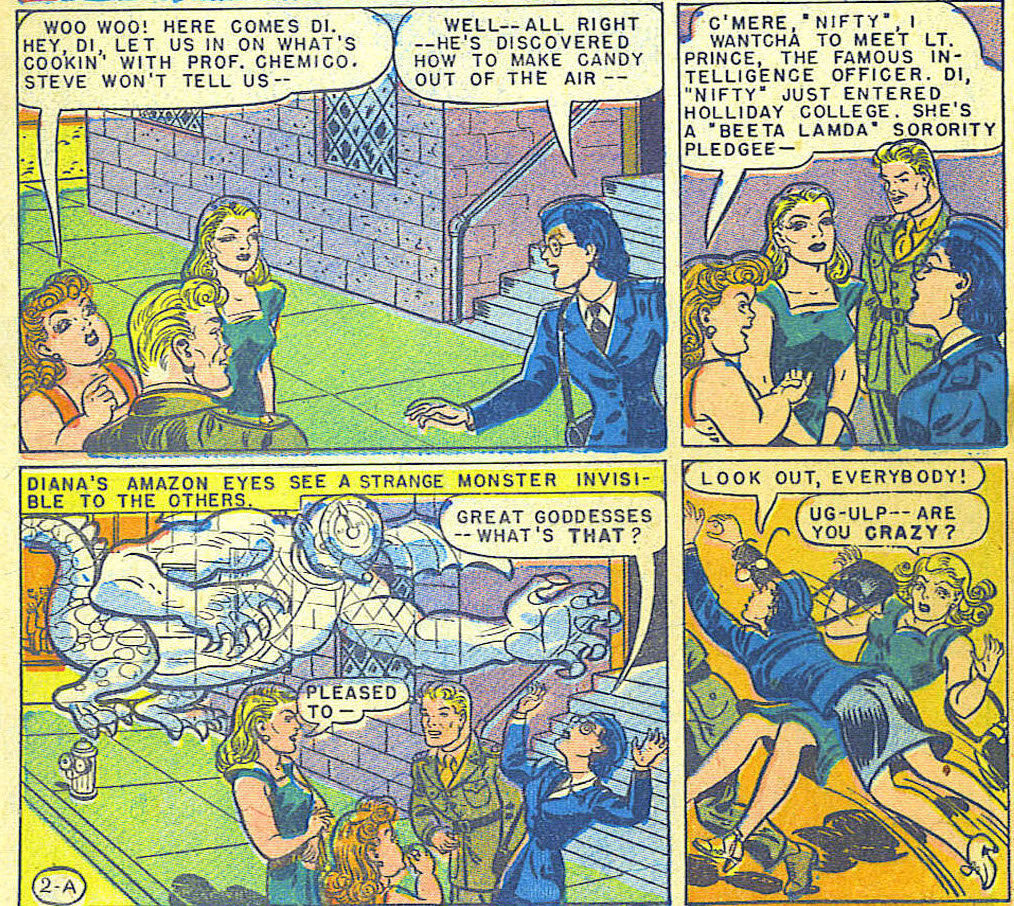

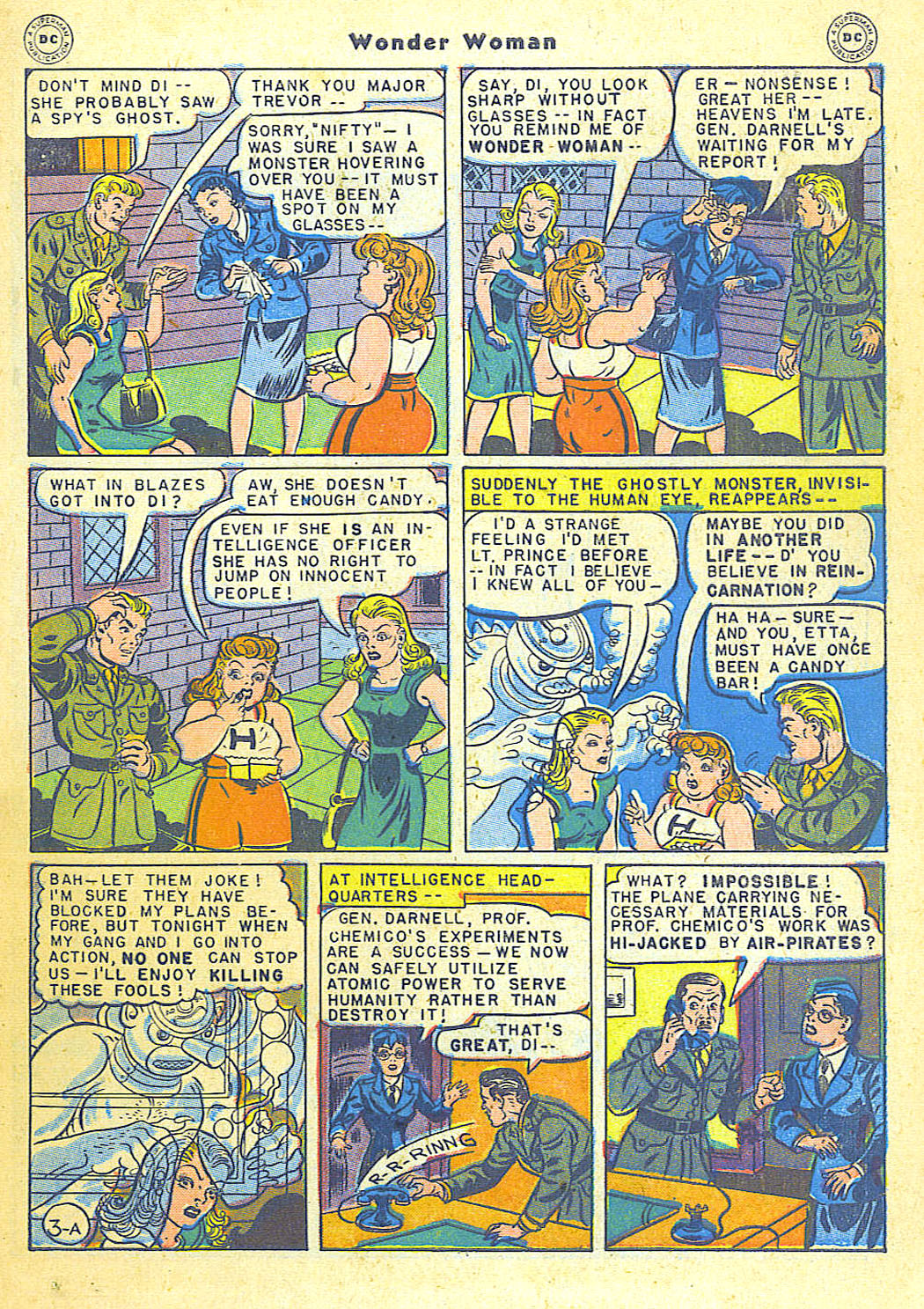

Or this bizarre backlit Etta as femme fatale from the second story.

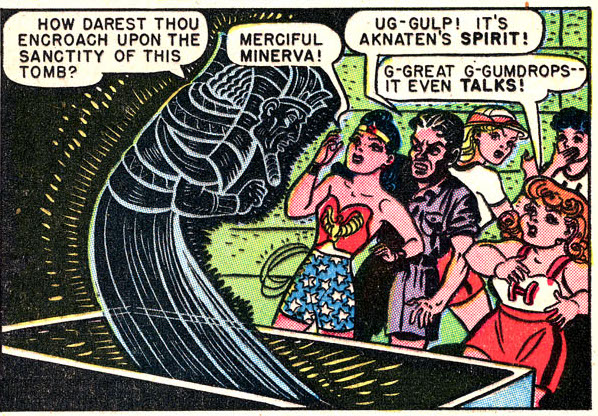

This weird Egyptian ghost rising from the tomb is pretty fantastic too….

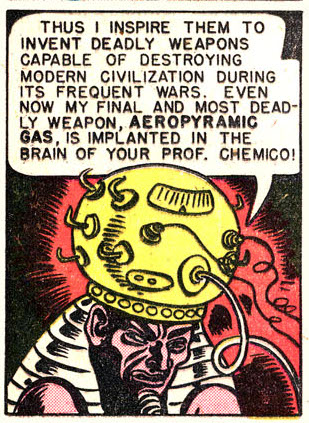

And how about this ancient Egyptian headgear?

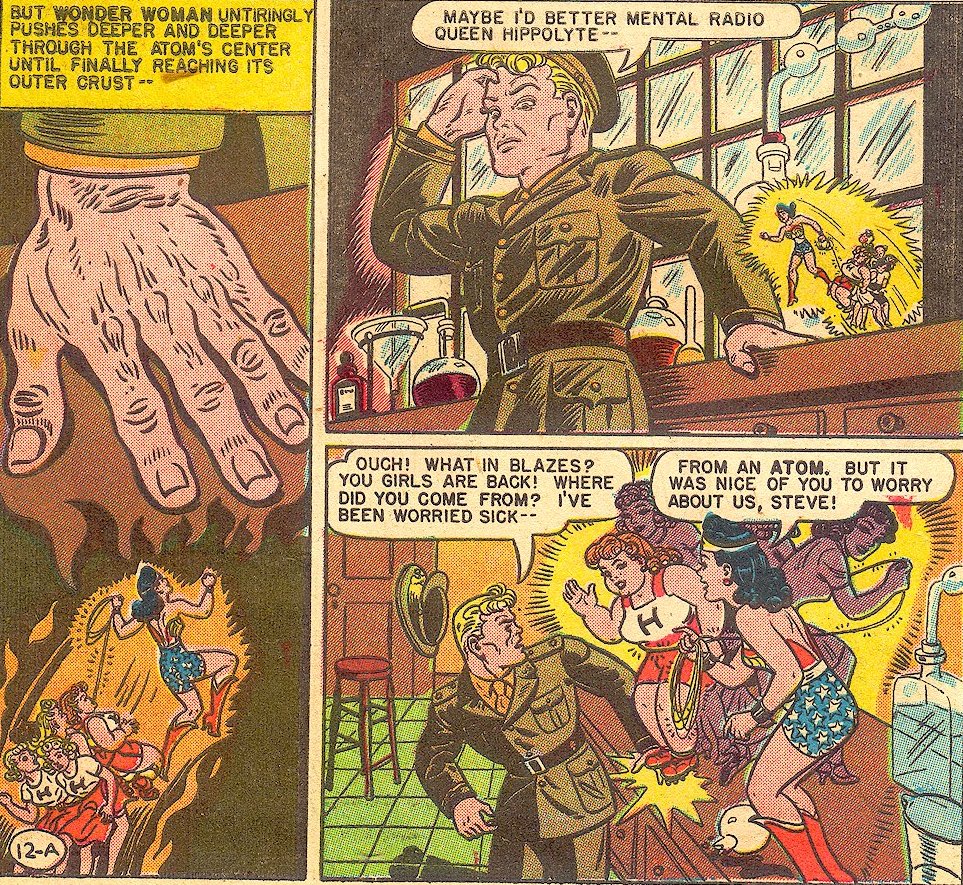

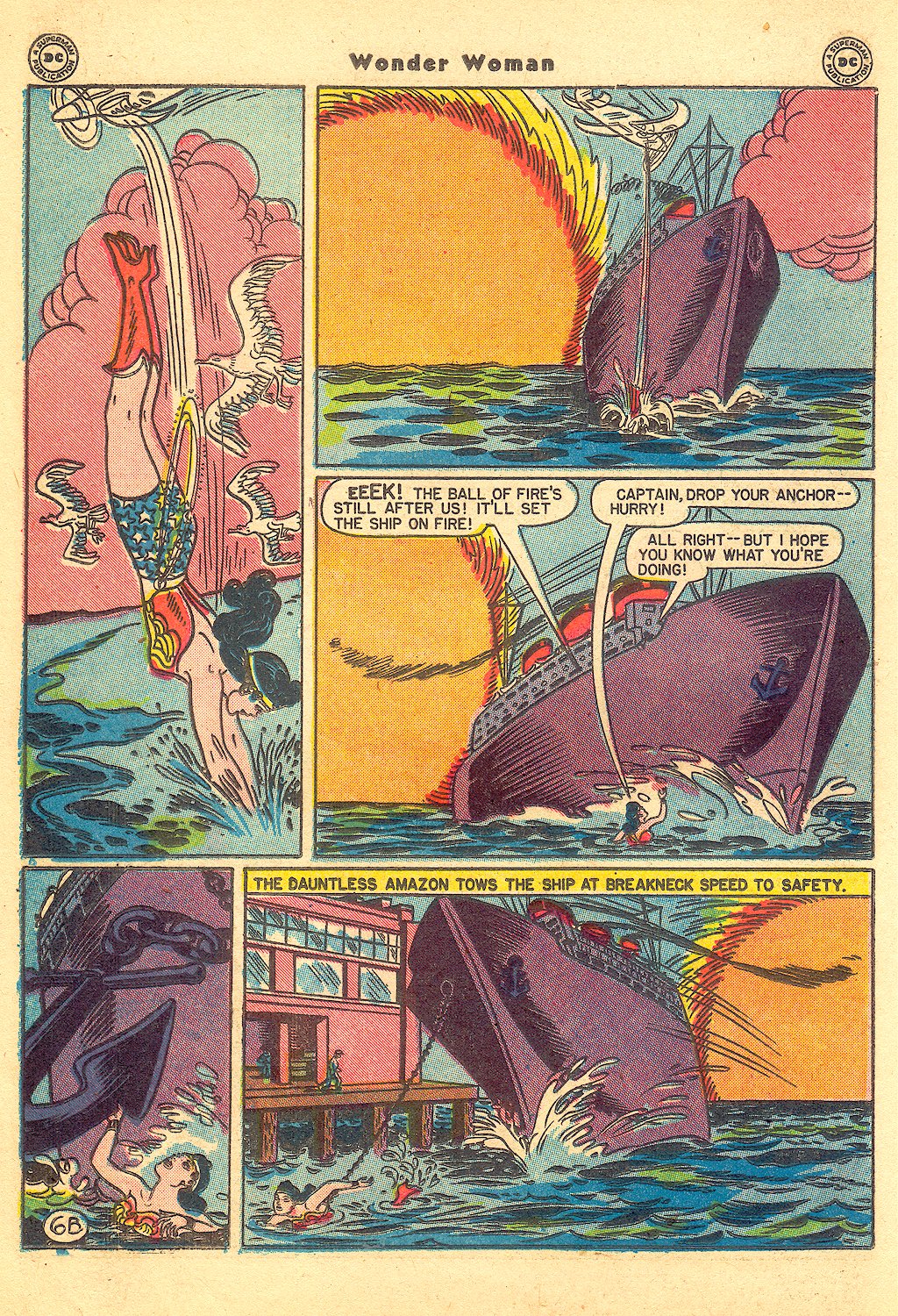

Storywise there’s not a whole lot going on here; Marston makes some noises about the evil dangers of superweapons and generally suggests he doesn’t want the world to go to war again. It’s fine…but the art is definitely the main thing here.

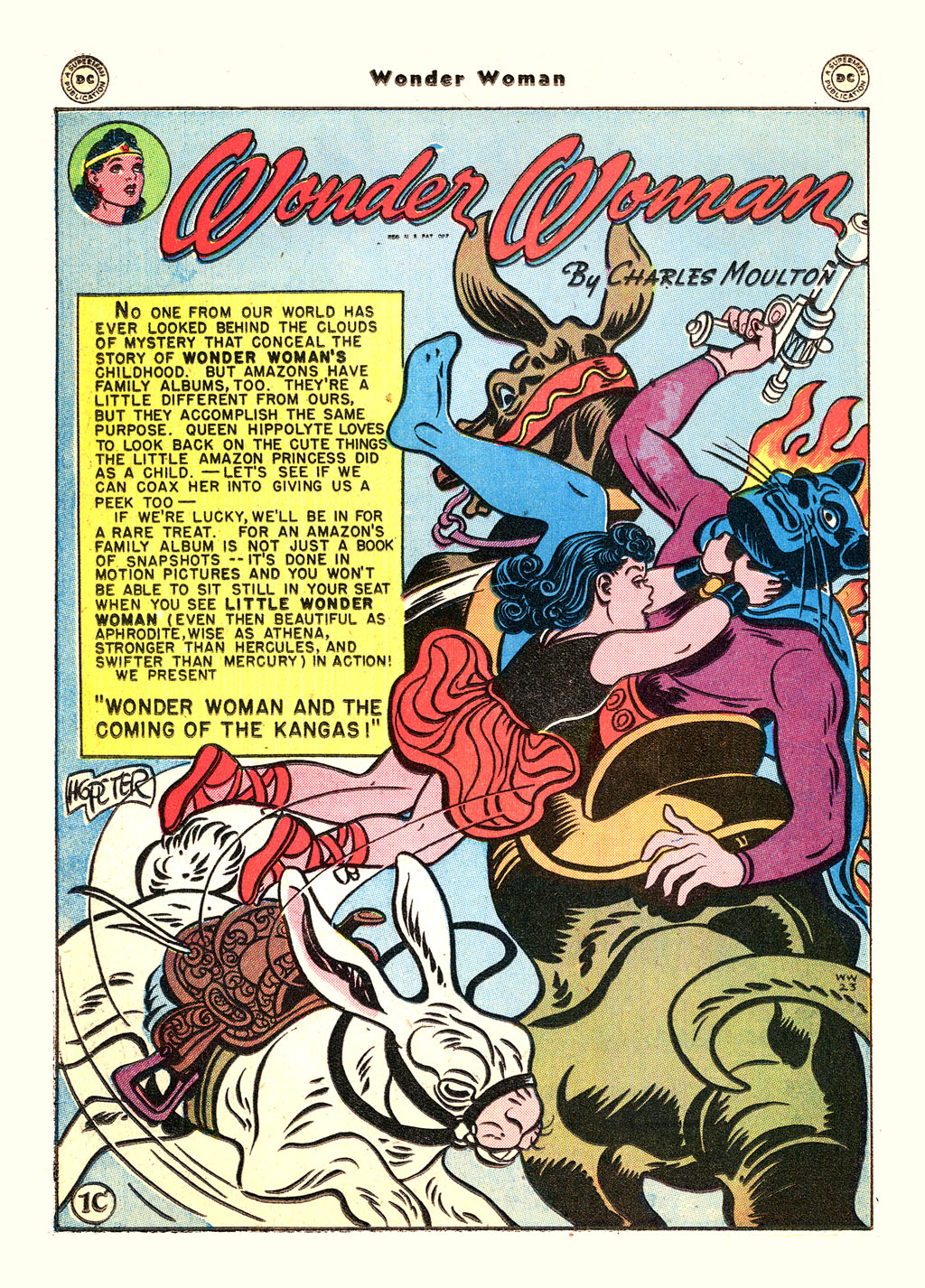

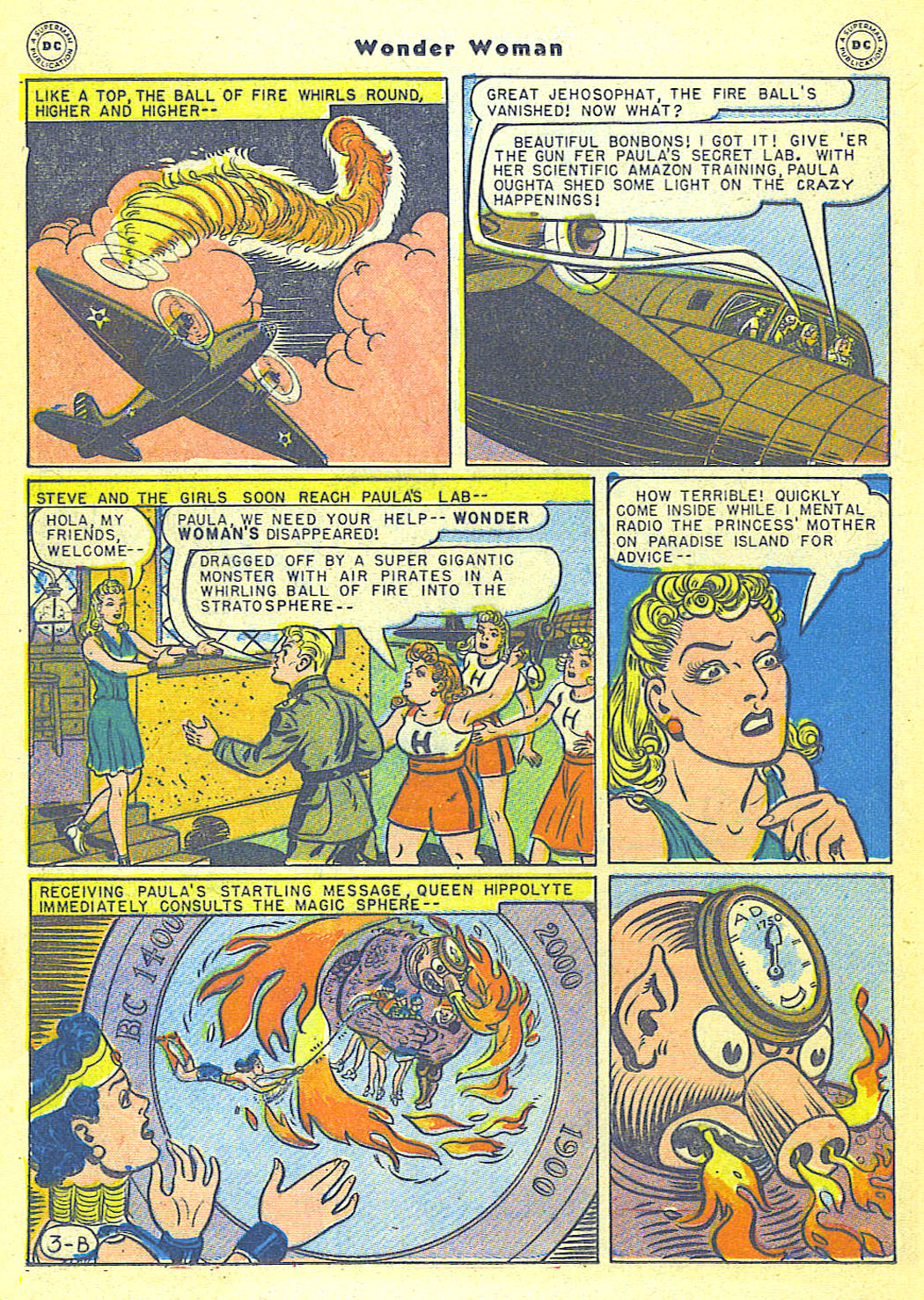

The third story is the most interesting of the lot. It’s a tale from WW’s childhood, explaining the origin of the giant sky kanga’s. Also, incidentally, it lets us know that before there were sky kangas, the Amazons rode on giant bunnies. What is the origin of the giant bunnies? That, alas remains a mystery….

As always, Peter’s animal drawings are something special. The lines of the giant bunny and the giant kanga flow sensuously; the whole page is filled with sensuous curves. And the sensuousness adamently includes the prepubescent Wonder Woman herself; her short frilly flared red dress placed in the center of the composition.

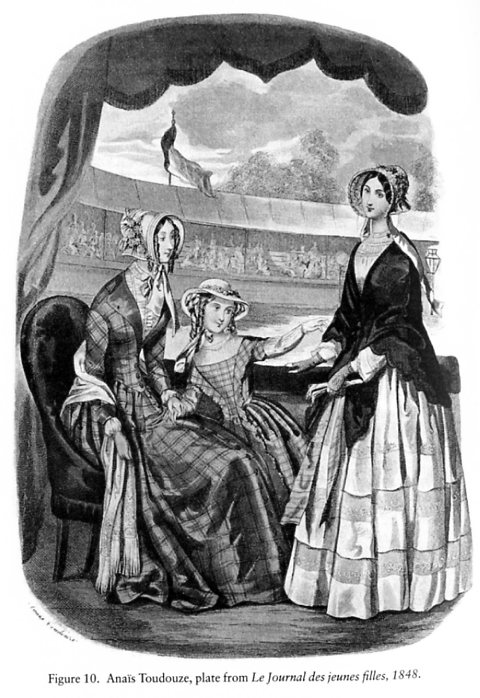

In Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England, Sharon Marcus argues that the eroticization of female children was a common iconographic trope of Victorian fashion illustration, as well as of Victorian society more broadly.

Victorian culture represented girls as epistemological paradoxes, so innocent that they could be intensively eroticized without raising comment. But unlike images and stories that eroticized girls for a mixed audience of men and women, fashion imagery displayed girls in erotic dynamics with adult women for the delctation of a female audience. In The History of Sexuality, Foucault argued that the intensification of family ties in the nineteenth century also sexualized them, and fashion plates show that in the process all cross-generational ties were eroticized, including those between adult women and girls…. Designed to be objects of an appreciative female gaze inside and outside the image, girls in fashion plates also embody a desire to look at and touch a woman, a desire figured as both self-abasing and self-important.

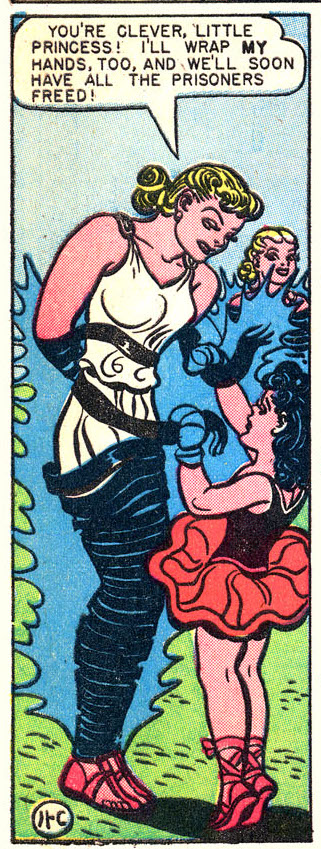

Marston reproduces this dynamic even more self-consciously than the fashion plates:

WW’s “childish tricks” (involving, essentially, disrobing at super-speed before her mother), lead Hippolyta to remember her daughter’s actual childhood. The eroticized affection between mother and daughter is then displayed (via film) for the delectation of an all-female audience.

In her discussion of the Victorians, Marcus follows her look at fashion illustration with an analysis of debates about corporal punishment in women’s magazines of the period. Said debates involved numerous women writing to the magazines to describe, in detail, their own experiences with corporal punishment — descriptions which dwelt on the removal of clothes, the physical sensations of whipping and being whipped, and other immodest details. All of this, according to one magazine editor “aroused…intense, not to say passionate interest.”

Here’s one letter which Marcus quotes.

I put out my hands, which she fastened together with a cord by the wrists. Then making me lie down across the foot of the bed, face downwards, she very quietly and deliberately, putting her left hand around my waist, gave me a shower of smart slaps with her open right hand…. Raising the birch, I could hear it whiz in the air, and oh, how terrible it felt as it came down, and as its repeated strokes came swish, swish, swish on me!

Marcus notes that “Corporal punishment is where pornography, usually considered a masculine affair, intersects with fashion magazines targeted at women.” She adds that “flagellation scenarios represented, interpellated, and excited women as well as men, and that the power differences inherent in scenes of discipline and punishment were erotically charged in any gender configuration.”

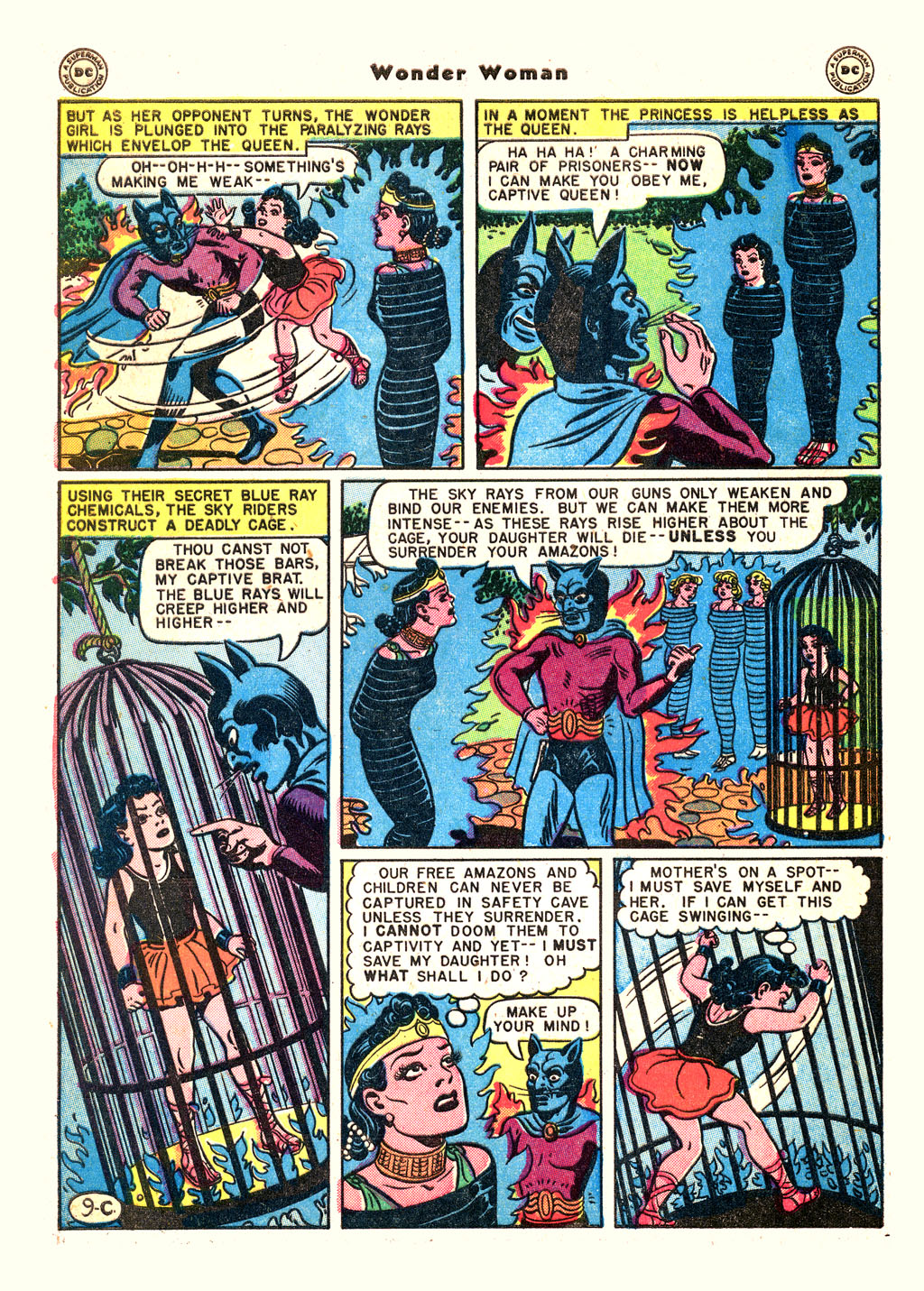

So here’s some scenes of the young WW being disciplined as little girls ought.

That upper right panel, in particular, eroticizes the adult mother and the child daughter in exactly the same way; both are bound side by side, with Peter’s stylized drawing and the wrappings deemphasizing the age difference; they look like different sized dolls rather than like mother and daughter.

Peter emphasizes the connection, and the parallel fetishization, of mother and daughter in other ways as well:

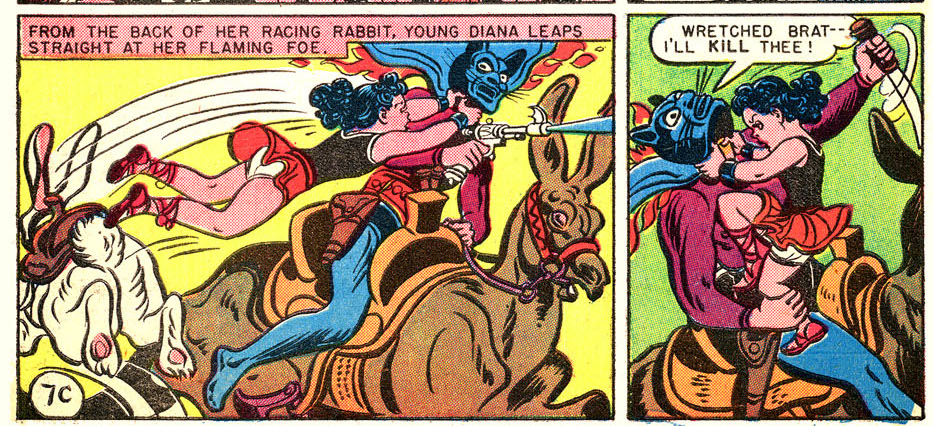

Mother and daughter both attack in the same way; leaping up to grab the antagonist by the neck. And in both cases, the attack is, I’d argue, fetishized; Hippolyta’s straight posed stiffness emphasizes the curves of her dress and of her breast. In the second sequence, Peter shows us, in both panels, WW’s underwear beneath that short miniskirt.

In addition, of course, any display of female power is eroticized for Marston, as is any display of female disempowerment. As with the corporal punishment fantasies Marcus describes, the woman empowered and the woman disempowered are both subjects of the fantasy. So it’s as exciting to see WW in the cage as to see her breaking out of it:

Note in the bottom left panel that we see her underwear again…and that her crotch is level with her mother’s face. The energized swoops of motion lines; the violent rescue of the damsel in distress — this is a typical erotic fantasy, not any the less so because it involves daughter/mother rather than hero/heroine.

You see it again here; the Amazon being unwrapped is decidedly butch; her shoulder-width emphasized by the narrowing of her lower body caused by the wrapping. Young WW, with her dress flaring up as always, is decidedly femme. But in this case the femme is rescuing the butch, rather than the other way around — a role reversal which I’m certain Marston appreciated.

And speaking of role reversals:

The sky riders who the Amazons initially assumed were men are, as it turns out, masked women. Thus Aphrodite’s law preventing men from setting foot on Paradise Island is not broken. Or, to put it another way, men are not the defilers of Aphrodite’s virgin soil — women are. Inevitably, the sky raiders are stripped to their underwear and bound under the watching eyes of the Amazon. In defeat, the powerful men are feminized — though, since this is Marston, the feminization is actually their triumph, as they will now (eventually) become reeducated and made Amazons (better than any man!)

Marcus notes that the Victorians created eroticized images of and narratives about women for women. The fashion plates allowed women to experience powers and pleasures around control and consumption of female bodies that were, in other areas, reserved for men. In a somewhat analagous way, it’s worth pointing out that the eroticization of children in WW is meant to be consumed primarily, not by adults, but by children. The hints of adult pleasure, power, dominance, and submission, leavened with childish adventure and playfulness — the very things that made Frederic Wertham choke up his soup — were, I’d guess, exactly the features which appealed to children of every gender.

Plus, of course, sky kangas.