The Rub at Magic Futurebox

This last weekend I traveled into the depths of Brooklyn to witness The Rub, a re-envisioning of Shakespeare’s Hamlet done by a small troupe, the Tremor Theatre Collective, which includes my wife and fellow Hooded Utilitarian Marguerite Van Cook in the role of the young prince’s mother, Queen Gertrude. After Marguerite’s many late rehearsals, she’d tell me of the unusual methods of director Nessa Norich, an innovative theatrical force emerging from France’s Jacques Lecoq International School of Theatre. Norich’s actors formed the production from improvisation, from physically interacting with each other and with the deep columned space of the host theatre Magic Futurebox. From weeks of coaxing and collating the freely invented dynamic interpersonal movement and gestural variations of her cast and imposing a anachronistic montage of verbal and visual references, Norich finally introduced a script in the last week of rehearsals. As I was trying to help Marguerite run her lines, they seemed almost peripheral to the source text with only scattered bursts of Shakespearian diction, but Norich’s presskit describes a “surreal and playful investigation of the frustration, anxiety, passion, complacency, selfdoubt, delusion, isolation and desire that come with being heirs to a state rotting from the inside out.” That’s basically what our Will was on about, as well as where we Americans seem to be at. When I actually saw the results of Norich’s intriguing construct, I found that Shakepeare’s narrative is well represented even as it is made part of something contemporaneous and electrifyingly involving.

The Rub: Gerson, Van Cook and Stinson. Photo by Nessa Norich

The character of Hamlet is effectively played by several actors: one (Micah Stinson) sulks and simmers while another (David Gerson) adopts a keenly fearsome, sinuous aspect of outrage held barely in check. Three more Hamlet alters argue by turns and interweave at breakneck speed through the cavernous room (Colin Summers, Daniel Wilcox and Steven Hershey, who also flow seamlessly into a mellow-voiced Laertes, a loquacious Polonius and an opportunistic King Claudius, respectively). Queen Gertrude’s role is here expanded to be a fiercely comedic whirlwind of Freudian complication. I can’t claim objectivity, but it’s awesome to see Marguerite use some of her many performative skills. As Gertrude she works the stage like a vaudevillian; she stalks with limber, cartoony malevolence, she flummoxes a game reporter (Chas Carey) like a Danish Ghaddafy, she purrs, cajoles and overtly schemes with her new husband against Caitlin Harrity’s earnestly vulnerable Ophelia. Site-specifically mapped projections cunningly use the architecture of the theatre to add ominous, surreal narrative elements. The audience is brought out of their seats to follow the scenes into the depths of the room, making them complicit in the action as it boils to its inevitable final conflagration. While it certainly adheres to the spirit of Shakespeare’s intent, The Rub also shows a freedom of conception that to me is the essence of Art. I love it and so does Magic Futurebox, who have extended the production through next Friday and Saturday.

The Rub @ Magic Futurebox: 55 33rd Street, 4th Floor, Brooklyn, NY (D, N, R trains to 36th St) on Friday Feb. 17th at 8pm and Saturday Feb. 18th at 8pm

______________________________________________________

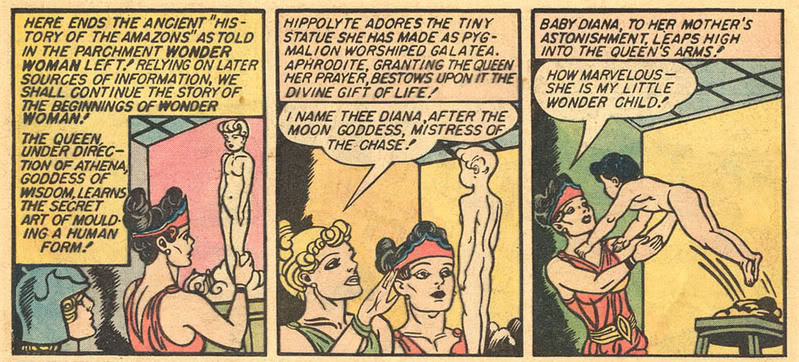

Before Watchmen: Too Sullied Flesh

Shakespeare’s plays are in the public domain; he left no heirs but he is always credited as the source of any use of his works because his efforts are of undisputed quality and value. I suppose it is possible that the more extreme liberties taken by the Tremor Collective might put some Shakespeare purists’ noses out of joint, but theatre is by its nature an act of interpretation. It is a given that a source play is subject to adaptation. Plays are meant to be reimagined through the efforts of the director, actors, set designers and other members of the ensemble putting up the production. This is not the case with the current news cycle bummer about DC Comics’ reworking of co-authors Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen, a book that was not conceived with the intent that it should be re-interpreted by other creative talents, on the contrary: Watchmen could not be a more deliberately complete work than it is.

As it has stood for 26 years, Watchmen has gone through many editions and enriched DC Comics financially and in terms of credibility. In fact, this multifaceted work is virtually the jewel of their crown. It is one of the key books that began to give comics a degree of critical acceptance, and it is one that deserved such attention—it gave the company a cache to build on, which they have sometimes tried to do with their more ambitious efforts such as the Vertigo line and their similarly convoluted graphic novels, story arcs and miniseries. They could have continued to profit from Moore and Gibbons’ book and striven to emulate their example of excellence, without violating the bounds of decency. But that was not to be. First, Moore disowned the adaptation of Watchmen to a film by Zack Snyder and for a good reason: the comic stands as a finished and hermetic work of Art in the form of a comic. I doubt that he could anticipate how bad the movie would be, though; it reglamorized the violence which Moore and Gibbons had taken pains to deglamorize, changed the ending entirely and amplified what I see as the flaw of the book.

Watchmen: Sally Jupiter is sodomized offpanel; and the “cover-up.”

Make no mistake, what Edward Blake does to Sally Jupiter is not attempted rape, it is rape. He assaults and beats her, then sodomizes her. This is a DC comic and so we are not shown explicit penetration. Instead, the rape happens in a space of indeterminate timing between the first two panels shown above and outside the cropped image of the second panel, where the two characters’ relative positions, Sally’s choked scream of pain and the symbolic bestiality represented by the ape’s head in the case make abundantly clear what is happening. In panel 3, Blake isn’t removing his pants, he’s pulling them up. The colorist has obscured where Gibbons drew Sally’s shorts and stockings pulled down in panel 4, which represents a typical male reaction to rape, at the time and often still. Hooded Justice’s harsh direction to Jupiter to cover herself can be seen as an indicator of why both her daughter Laurie and Hollis Mason (in his book excerpt within the book) are unaware that the rape was actually perpetrated in full: the truth had been suppressed.

Laurie is given clue #1 that Blake is her father.

Jupiter’s previous flirtations with Blake are used as justifications for her contemporaries to think that she had somehow “brought it on herself” and Jupiter’s own feelings of shame and what can be seen as typical victim psychology cause her to diminish the crime, to the extreme that a decade later she has an affair with Blake, which produces a child: Laurie.

In Laurie’s childhood memory, Sally tries to explain to her husband why she has a tryst with Blake, the rapist; confronted by Sally, Blake gives out with clue #2; and their daughter’s epiphany on the moon.

Hammering the offensive flaw: Sally loves her rapist.

Sally kissing the photo of the late Blake amplifies the flat note in what is otherwise one of the most carefully and sensitively composed comics ever done. In a medium predominantly directed to males, an often overtly misogynistic form oblivious to the consequences of sexual violence, this rare realistic depiction of rape in comics comes to represent a offense a woman could forgive, that she even might even come to love her rapist. Even more offensively, Snyder in his film made the fact of Laurie’s very existence through Sally’s forgiveness be the salvation of the world. This concept unfortunately lurks in the book, but shorn of the larger rationale of Moore and Gibbon’s ending which involves the human race uniting in the face of a manufactured outside threat, in the film the forgiveness of the unforgivable, the purpose of conception superceding a woman’s rational sensibilities, the “miracle” of the existence of even the product of a rape, all become the primary lynchpins of a narrative seemingly altered to pander to Christian Americans.

For his part, Moore removed his name and refused to profit from this adulterated mess, while he ensured that his collaborator and co-author Gibbons was the sole beneficiary of any royalties. Moore and Gibbons always steadfastly declined to do any more comics with the characters of the book and for 26 years DC respected their contribution to DC’s standing enough to let it go. It should be noted that a production of new comics like Before Watchmen did not happen under the watches of the more sensitive Jenette Kahn or Paul Levitz. No, it takes a corporate pitbull like Dan Didio to make such a decision. With the recent announcement, Moore immediately registered his protest and Dave Gibbons—well, unlike Moore, he still works for DC on occasion, so I’d guess that he couldn’t risk anything but a vague “good luck with that” statement. DC’s behavior, along with Marvel’s recent anti-creative legal victories, should send a cold chill through comics professionals.

And that brings one to question the involvement of all participants. Now, I shudder to imagine that I was more of a “team player,” that I hadn’t bitterly complained about such things as inequities of cover credit, that I drew in a still gritty but somewhat prettier style and had somehow “moved up the foodchain” of artists who draw for DC, or that Brian Azzarello in a generous mood had decided to throw me a bone for drawing his very first professional script, the results of which pleased Axel Alonso so much that he made his new writer a star, and Azzarello had actually recommended me for a gig. Okay, that’s a little poke at Brian, but let’s pretend that for any of these reasons I had been actually offered the Rorschach title. Then I would have been faced with the painful prospect of turning down such a very high-paying, high profile job for reasons of ethics. It’s hard to come down on people who need work. “Tough economic times” can be a powerful incentive to ethical compromise. But one wonders whether people as successful as Azzarello, Darwyn Cooke and J. Michael Straczynski need the work. Rather, they seem to all believe that they are entitled to presume on Moore and Gibbon’s masterpiece, because they are bursting with their own “stories to tell” about the characters. One wonders how they would feel if the shoe is on the other foot and it was their brainchildren at stake. Regardless, their presumption shows a disregard for comics as an art form of any significance and disrespect for the accomplishments of their contemporaries.

It gets worse: given that the actuality of the rape has been debated, one wonders how the re-interpreters will further mangle Moore and Gibbons’ intent. One might dread Cooke’s version of the adolescent Laurie in Silk Spectre, even if it will be drawn by Amanda Conner, because Cooke, known mainly for his reinterpretions of others’ creations, in his first adaptation of the appallingly misogynistic Parker books invalidated any claims of sensitivity or irony in his approach by having the lack of taste to render all the female characters with his typical cute Batman Beyond template. What one gets is interchangeable, expendable girls dying cutely for no reason at all, while the main character could care less. It doesn’t bode well and the covers of the new comics released so far carry out a theme of disempowerment, some directed deliberately at women, as Noah showed in his HU post yesterday. A general theme of uncaring seems to blanket Before Watchmen; as Azzarello stated in The New York Times what seems to represent mainstream comics’ overall regard for their audience’s intelligence: “a lot of comic readers don’t like new things.” Jack Kirby must surely be spinning in his grave. Perhaps Azzarello in his case was being ironic, but he couldn’t be more clear that one won’t be seeing anything new in Before Watchmen.