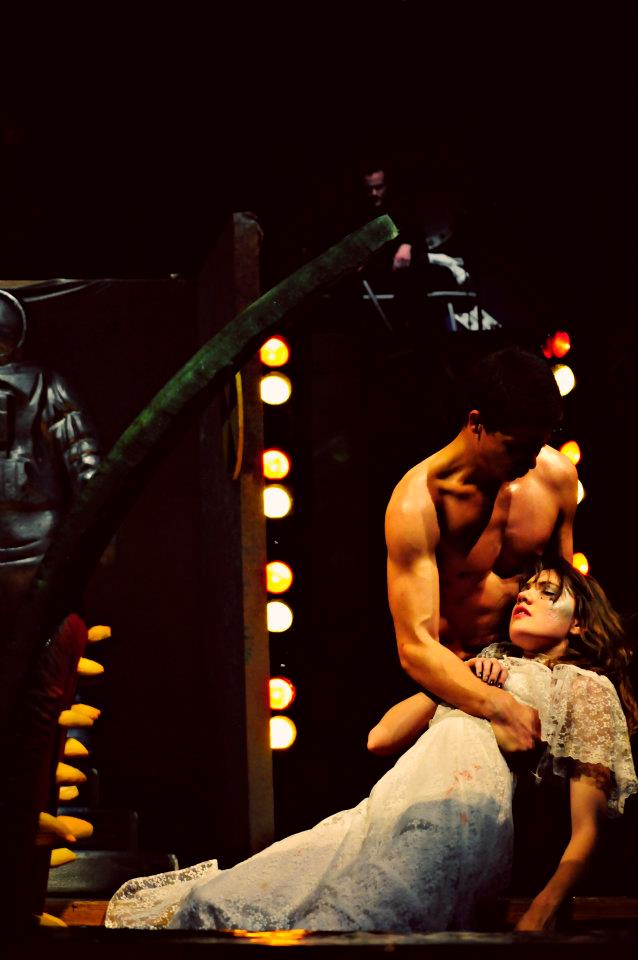

Sara Villegas and Anthony Pyatt as Anne and Peter.

Anne Frank and Peter van Daan flirt playfully in the crowded attic space, alternately shy and forward. They move lightly and talk softly, all to the accompaniment of a delicate instrumental on piano, guitar, flute and glockenspiel. It’s the first few notes of “We’ve Only Just Begun,” the treakly ballad co-authored by Paul Williams and Roger Nichols for a bank commercial in 1970, and later popularized in a syrupy easy listening version by Richard and Karen Carpenter. But, beyond the intimacy of the stage and among the small watchful crowd, the audience doesn’t seem to recognize it—or if they do, it’s a slight titter of recognition, and then transformation, the overtly sentimental lyrics (“We’ve only just begun/ to live/ white lace and promises/ a kiss for luck and we’re on our way/”) replaced by a soft flute that sends out echos of memory of these sentiments, the words casting delicate shadows on the moon-lit moment.

It was one strange moment of many in a forty-five minute performance filled with strange moments– 2011’s Anne Frank Superstar, a play constructed by Orlando high school theater teacher James Brendlinger, and acted, crewed and even directed (senior Cody David Price) by current students and recent graduates of Lake Howell High School. (A non-recent graduate, myself, was brought in as musical director.)

The show is the definition of high concept: The Diary of Anne Frank, set to the music of the Carpenters. Described by reigning Orlando theatre reviewer Elizabeth Maupin as “telling a sacred story through songs that have often been called kitsch,” the show was wild– and wildly successful, at least critically. The concept is almost stupidly simple, and some of the audience each night seemed prepared to hate the show, or at least mock it. After all, do “Rainy Days and Mondays,” “Yesterday Once More,” and “Top of the World” really belong in a story of profound loss and human tragedy, with a backdrop of indescribable horror?

But the success of the show– and if one can gauge a show’s success by what percentage of your audience is unable to stand after it is over, this one was truly successful—was directly due to this juxtaposition, a combination that set both elements in a new light, one that seemed to change each aspect of the material. Coming out of the mouth of an adult woman, a line like “hanging around/nothing to do but frown/ rainy days and Mondays always get me down,” is at best maudlin, at worst painfully trite, especially when set on a backdrop of gooey sentimental strings and turgid playing. But out of the mouth of an expressive, and doomed, teenager, the words are transformed into something sad, and possibly true. The songs were also served by the intimate arrangements consisting of piano, guitar, glockenspiel, oboe and flute, supplied by myself, two high school students, and the cast member playing Margot.

Likewise, the story of Anne Frank herself was transformed, or at least recast—it’s become so buried in weight and solemn reverence now that its easy to forget that the girl herself was a teenager, a pop culture enthusiast who wrote, drew, danced, had crushes on boys, worried about her period and her parents, who could have done so many things with herself but was instead doomed to never move on from that adolescent state. She is in many ways the ultimate teenager, having had all of the fears of adolescence made literal in her circumstance. For Anne Frank was trapped–puberty really was the end of the world.

There are additional resonances that present themselves throughout the play, both direct and tangential, including Karen Carpenter’s own doomed life. And much of the power of the play comes from the hopeful use of those songs, so hopeful that, by the time the Nazis actually arrive, it seemed as though the audience had managed to forget that they already knew the ending to this story.

But if the jubilant “Top of the World” and the small thrills of the budding romance have caused them to forget, they’re soon reminded by the violent, silent violation of the attic, accomplished as the three teenagers enjoy strawberries in the annex. After the violation of the attic and the tearing apart of the family, the ending sequence presents Mr. Frank on the now-bare stage delivering a monologue regarding the fate of his family, as footage of concentration camp victims inter-cut with an increasingly emaciated Karen Carpenter is projected onto a sheet held by two Nazis, to the mournful accompaniment of an instrumental of the Carpenters song “Superstar.” At the conclusion of this monologue his doomed daughter comes out one more time and touches his shoulder, to sing/whisper a few lines of the song. “Don’t you remember you told me you loved me baby/ you said you’d be coming back this way again baby/ baby baby baby baby baby/ I love you/ I really do.” He reaches back, trying to touch her hand, but she is a finger length beyond reach, led off stage by the waiting Nazis. Slow blackout on Mr. Frank, alone on the stage, and house lights up twenty seconds later. No curtain call.

It seems implausible on paper that anyone would attempt such a juxtaposition, or that any audience would stand for such a thing. But at every single performance the reaction was the same—the house lights coming up on a stunned and reeling audience, many of them still sobbing.

Here’s the thing I haven’t brought up yet, which doubtlessly many of you have already thought—the show was in every way illegal.

The Carpenters songs were not the biggest barrier—although it would be a convoluted argument, as long as we weren’t using the name or logo of the group in the promotion of the show, we would have a reasonable chance of making that portion work legally—you can, after all, perform covers of songs written by other people with simply a venue’s membership to ASCAP, and we could probably make the argument that having a repeating theater performance that happens to feature songs popularized by a certain group isn’t fundamentally different than an all-lesbian vegan Led Zeppelin cover band playing at the local ASCAP-member Mexican restaurant.

Anne Frank’s words, however, and the translation of her words on which we were relying for much of our text, were a different matter, as was the authorized play (Diary of Anne Frank), which provided much of the rest of the text. All of these elements are still under copyright, and will continue to be so for several years. (In fact, copyright in the theater is more restrictive than in almost any other field. You can, after all, read a book or listen to an album any way that you wish once you’ve purchased a copy–but to publicly perform a play one must conform to a dizzying array of limitations set out by the author or the author’s agents–usually, that every word of the play will be performed, i.e. no cuts or insertions without permission, and that the appearance, gender and even staging etc will honor the stated intentions of the author regarding the script and contract.)

It’s no secret that a certain entertainment megalith has spent the past fifty years waging a war on the public-domain, its army of lawyers doing its damnedest to insure that their prized Mouse never legally becomes the public figure that he is. But its been only very recently that the full consequences of this have really been examined in the public sphere. The kind of theater that we created is not an unknown phenomenon—it’s just rarely seen in theaters. Instead, you’re more likely to see works that collide concepts with abandon on the Internet, in streaming video—in short, in places where authorship is more unsure and its not always clear who’s neck is on the line.

And I have no doubt that a not-insignificant portion of the people reading this might think, at first blush, that this is fine—that there’s no compelling reason for such a perverse transformation, and that if there’s a law to prevent such a perversion, all the better.

But at this point, seventy years after her death, is there any person that should be able to claim the words of Anne Frank? Is there any one person that can speak for her as directly or truthfully as she spoke for herself? Who owns her words? Who owns her name?

Victoria Camera as Margot.

The show was the brainchild of high school theater teacher extraordinaire James Brendlinger, who, as a young boy in rural Pennsylvania filled scrapbooks with elaborate collages, depicting himself rubbing elbows with celebrities cut from the pages of the dozen odd magazines to which he subscribed, cut from the pages to mingle with each other, with himself—a glorious life of rubber cement living rooms and glossy paper courtship. Concurrently he filled binders with his other love, never-ending Gothic soap opera novels of his own creation, the concepts and characters lifted in the beginning from episodes of Dark Shadows and slowly over many years grown, like the show that spawned it, to monstrous proportions, labyrinthine and tawdry and tangled. (Dark Shadows itself, of course, lifted these concepts itself, whole cloth, from an array of Gothic horror novels)

But after graduating college with a teaching degree, James didn’t move to glamorous Hollywood, but to Hollywood’s hick second cousin to the south—Orlando, FL. He took a job at Lake Howell High School, which is where I met him in 1998, during his first year.

Since then he’s put almost fifteen years into well over a hundred plays and projects at the school, an incredible tally of productions. But somehow he makes it happen, with an incredible expansiveness and a desire to involve as many students as possible.

This ties in nicely with his tendencies for the grandiose, for making something as big and as bold as it can possibly be—always more songs, more choreography, more dancers and aerialists and elaborate props and staging. After graduation I occasionally contributed to this craziness, lending a hand with set design and visual conception, and eventually supplying music. Most of his plays have virtually none of the “restraint” of AFSuperstar. Most of the time they’re much larger, as grandiose and spectacular as possible.

One of the more recent of these provides an interesting point of comparison– a little play called SpaceMacbeth, written by (ahem) William Shakespeare.

Jordan Wilson and Cara Fullam as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth

The title and the concept were mockingly suggested to Brendlinger via an angry multiple-page letter from a theater professor from a local private college who was upset by one of Brendlinger’s earlier adaptations of Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, which featured two “sisters” in the roles of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth. Like its predecessor, SpaceMacbeth is the sort of play that, by virtue of its dense bricolage, defies easy description. (it largely defied logic or common sense as well, but that’s another matter.) Rather than attempt to summarize, I’ll hit you with a few highlights–

–a live band (consisting of piano, marimba, violin, flute, oboe, guitar and drums) to one side of the stage, a thicket of mannequins to the other side, both plastic and flesh. It appears that the three witches stir up so much malice and death not only for their own amusement, but also to expand their collection of mannequins, which continues to swell with the bodies of the dead as the show continues.

–dozens (a hundred?) references to various tawdry pop-culture science fiction films and television series, ranging from the obvious (teams of astronauts and “space ninja” in mass battle), to the bizarre (tremendous flesh-eating puppets at the front of the stage to which Lady Macbeth delivers her enemies as food) to the inexplicable (previously mentioned astronauts entering the stage in march to an a capella rendition of the “Star Blazers” theme song).

–a truly berserk, yet somehow still believable, Lady Macbeth, played (and sang) to perfection by senior Cara Fullam. When she’s not busy scheming and pining after her husband, Lady Macbeth spends the first act concocting various ominous experiments, including creating giant dancing spiders with the aid of her nuclear reactor and designing some kind of sonic weapon while singing Kate Bush’s “Experiment IV.”

–At the top of act two, Banquo and the other slain men are reanimated by the witches, as drag queens. The witches explain their process, if not their reasoning, in an elaborately choreographed performance of the Scissor Sister’s “How Do You Make A Lady.” In the subsequent dinner scene Banquo teases Macbeth coyly from various places atop his giant castle machinery, batting her eyes, waving her hands and blowing kisses at the increasingly distressed king.

–Lady MacBeth’s final scene is sandwiched by two dramatic vocal performances. The first is a funereal version of Lana Del Rio’s “Video Games,” delivered as she drags herself out of bed to dispose of the evidence of the murders by feeding them to her giant pet at the front of the stage, who eats the bloodied clothing and weapons whole. She then disposes of the rest of her possessions in a similar way before dangling her feet into the edge of the pit as her android attendants dance around her.

After lying comatose for several scenes as people talk about her bedside, she rises for one final song—the huge and truly theatrical “Dreams,” written by KISS co-writer Sean Delaney and previously performed by Grace Slick. Flanked by two Death’s Head creatures that emerge from beneath her bed, she stalks the stage gathering together all of her creations and attendants, so that she can kill them all in the frenzied climax of the song. “I believe in magic,” she insists, throwing her attendants into the pit. “And I believe in dreams.” At the final hit of the song she stands poised with the knife above her for a moment, before plunging it into her chest as her attendants pop up and slap the stage.

Here’s my question to you, gentle reader– does an event like this diminish Macbeth the play? Or is the play itself so strong, so elastic as to survive being bent even in such an extreme way? Is it a simple matter of repetition, that when a play has been staged ten thousand times something is broken, that it becomes untethered from some platonic concept of faithfulness and can instead be bent and chopped and rearranged at will? Or is it that certain stories or certain works of art are themselves impervious to adaptation, that the more spins one puts on a text like Macbeth, the more possibilities appear? Is it possible that so many adaptations, so many different stagings and interpretations and resuscitations have helped make the play what it is today, have in fact created that feeling of timelessness and “bottomless”ness that so many feel when they approach the material?

To my mind, a play like Macbeth has proved its durability, has proved that familiarity and exposure don’t have to distance, but can instead comfort in the face of the unfamiliar. I can’t pretend to know what audiences experienced when they saw the play, but I can remember for myself how those bits of familiar things interacted with each other, rubbed against each other, even changed each other by their proximity. And in my mind it’s in the best interest of all of our respective art forms to allow works to pass into this state, that there will be a time when these kinds of transformations will be legal after the death of an author, when the art that is capable of being made through juxtaposition isn’t outlawed, or kept from larger audiences by the will of lobbyists working for a company that was itself founded on the adaptation of public domain works.

I want to live in a world where Lady Macbeth and Lana Del Rio are neighbors, attend the same cocktail parties, sing the same sad songs, a world where a thunderous performance of Kraftwerk’s “Metropolis” is the perfect accompaniment for a blood-soaked space duel.

I want to live in a world where Anne Frank is free to sing “Rainy Days and Mondays” whenever she damn well pleases.