This is an excellent comic. Let’s get that out of the way first.

Next: Kieron Gillen, author of highly-regarded Thor reboot, Brit, music nerd, all-around good guy. He’s friends with Tom Ewing, of Freaky Trigger and Poptimist fame. And since I spend a lot of time lurking ILM, the message board that started out as a discussion page for Freaky Trigger – and is now a hotbed of professional music writers – and since I was once an obsessive Libertines fan – dubbed “the saviors of British guitar pop” by a certain segment of the British music press – I feel as qualified as (mostly) anyone to discuss the intricacies of his and Jamie McKelvie’s two-volume comic Phonogram, which is, basically, a passionate and detailed criticism of British music criticism. And there’s a third volume due out soon, so this is even kind of timely!

By the time the first volume of this series, Rue Britania, concludes, the music critic whose POV we inhabit – who might or might not be closely modeled after the author – has confronted his post-teenage disillusionment and bitterness and become a stronger, less douchebaggy person.

As heartwarming as this is, it doesn’t quite erase the sting of many pages that first establish the character as an asshole – or the fact that this asshole character’s pronouncements on music are, for the most part, the final word within the comic on tons of indie bands you’ve probably never heard of (although the sting is somewhat lessened by the inclusion, at the end of the book, of a much less self-important glossary of terms and bands).

That, and the fact that Rue Britania is well-written, well-paneled and well-drawn, more than justifies its sequel, which not only sees the return of the narrator as an older, wiser, and more feminist person, but also foregrounds the series premise that there are many different ways to be a passionate fan of pop music. Plus, half the viewpoint characters are women! And it’s in color! No wonder The Singles Club sold way better than Rue Britannia (see comments for author correction).

In order to fully appreciate the narrator’s personal growth by the time of The Singles Club, it’s necessary to first start with the egotistical dick of Rue Britania. So that’s what I will be doing in this post. My next post will focus on The Singles Club, and when Volume 3 comes out, I’ll review that one too. Without further ado:

PHONOGRAM: RUE BRITAINIA

Is a comic about the damage music critics do to young impressionable teenagers when they overhype acts as “the saviors of British guitar rock.” Alternately, it’s about the damage specific rock acts do to impressionable young fans when they overhype themselves as the saviors of British guitar rock, even if – especially if – they believe it.

At this point I should probably explain this whole “saviors of British guitar rock” thing. It’s a long story, going back to Beatles and the Stones. Since then there have been many mutations – the Kinks and Small Faces and the rest back home in England in the 60s; Nick Lowe and Elvis Costello and their Stiff Records cohort in the 70s; the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays and other Madchester acts in the 80s; and then Britpop bands like Blur and Oasis, who saved England from the twin evils of Americanization and grunge in the 90s. Of course this is a gross simplification, but that’s kind of the point.

The aughts version of this cyclical narrative is tied up with the Libertines, according to some, or is a shameless and transparent attempt on the part of the music weeklies to pretend that they are still relevant, according to others – including, more than likely, the narrator of Rue Britania. Anyway, suffice to say that there is a long lineage of (mostly) two-songwriter bands in England that are somehow uniquely homegrown; and there’s also a British music press hungry to find the next group it can slot into this lineage (for ease of hype).

Our Hero can’t get over the narrative that has coalesced around a scene he was intimately involved in – he’s incensed that the bands he remembers as being actually central to Britpop – especially the female-fronted indie band Kenicke – have been forgotten in favor of a more convenient media narrative that it was really all about Blur, the snotty middle class art school savants, vs. Oasis, the rags-to-riches working class dreamers. His pain is twofold: one, that the press is trampling all over what actually happened; and two, that he can’t seem to shrug off his massive personal investment in what is – more and more obviously – a dead scene, and move on.

His pain is the pain of any very serious music fan who cares a great deal about the ways in which words and music construct reality, only to wake up to the laziness and willful misrepresentation of most music journalism. It’s also, although this has not quite formulated itself in the mind of the asshole protagonist, a kind of proto-feminist rage. Why are so many of the female-fronted groups being written out of the narrative?

In The XY Factor, Rhian Jones discusses the gender gap in professional music criticism. And in the comments, I drag my friend Sabina into an argument that the Rock Critic Establishment’s love of making lists and ranking things so as to determine their absolute universal worth tends to work against female-fronted bands, as the female fans who might have pressed for their inclusion in the “canon” tend not to relate to music in the same list-making way. It’s worth reading the original comment thread for Sabina’s take, which is much more nuanced than mine.

In any case, I bring this up not to fire another shot in the endless war of men and women, but to show that Gillen’s arguments, as ridiculously over-invested as they might seem, do have real-world consequences. Maybe Britania, the spirit of English Guitar Music, won’t actually fall down dead if culture warriors like the narrator cease to defend her. But these narratives do have power.

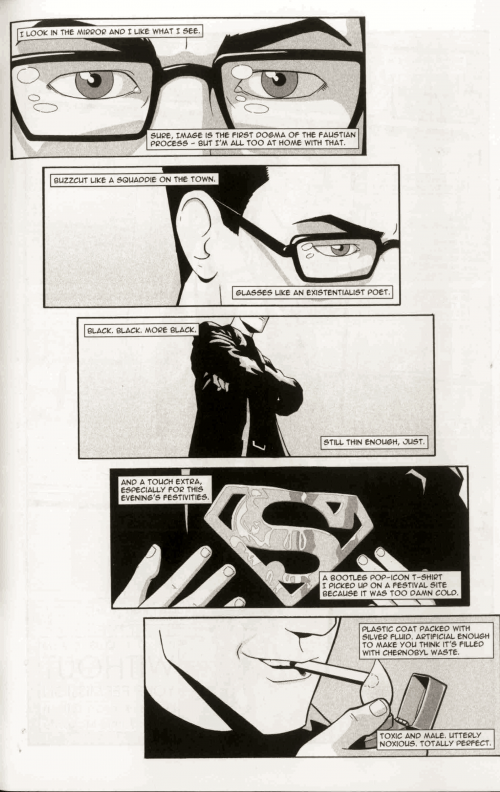

Going back to Kieron Gillen’s proto-feminism, though, here is the opening sequence of Rue Britania:

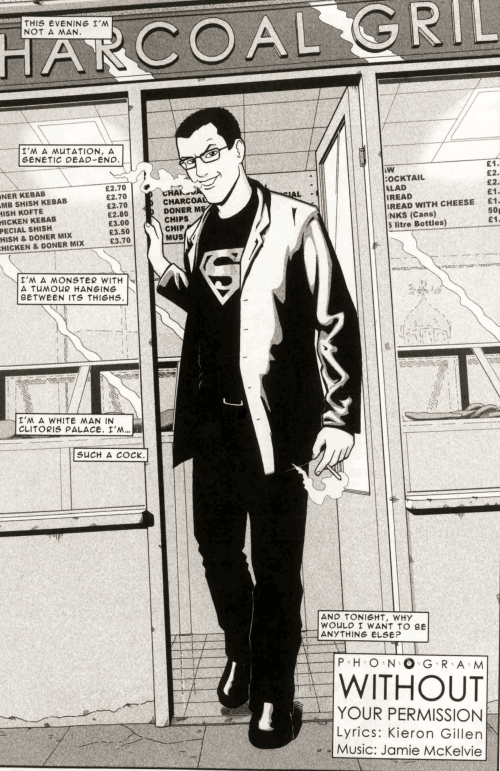

The narrator introduces himself as a toxic, noxious, assholish… man! With a bonus nod toward comics, the medium being used to tell his story.

As you guys know, it’s very important when attending a show to dress right for the occasion. You wouldn’t haul out the indie regalia for a Kings of Leon concert, but probably just show up in jeans and a t-shirt. By the same token, if you went to see Patrick Wolfe without glitter eyeshadow, you’d probably be underdressed. Our Protagonist, in this case, is very aware of this, and is putting a lot of thought and effort into his outfit: but towards precisely the wrong ends. He wants everyone at “Ladyfest” to know exactly how much he does not belong.

In other words, this guy is a huge dick! And not only is he a dick, he’s a self-constructed dick – which is even worse!

It’s not only that, though. His costume marks him out as a recognizable “type” – not just within hardcore music fandom, but as the protagonist of countless indie comics. His role in the comic, in other words, is not just to be there, but to explicitly display and acknowledge his obnoxiousness – and in the process, maybe, to reveal to the reader his own obnoxiousness.

That’s if the reader catches on. This is a fairly subtle comic – unlike, say, Scott Pilgrim, where Bryan Lee O’Malley starts out subtle but later aims with increasing unsubtlety to show the reader exactly how much damage well-meaning but willfully “clueless” guys can do to the girls they don’t care enough to work on their relationships with – so there is a chance that the reader won’t get it. Bryan Lee O’Malley has a whole series to make his points in, though, while Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvin have only this one volume of a trade publication they don’t expect to make money from, and they want to actually talk about the music, too. So perhaps this comparison is unfair.

Also, though, this guy is just such an asshole!! He’s way more of a jerk than Scott Pilgrim ever was. He understands pain, loneliness, and the female-fronted rock outfit Kenicke; but instead of using that knowledge for good, he uses it to sleep with vulnerable scene girls. Meanwhile, the girls he is friends with are those kind of ‘cool’ girls who will put girl-groups down with him and interrupt sex with their girlfriends for him.

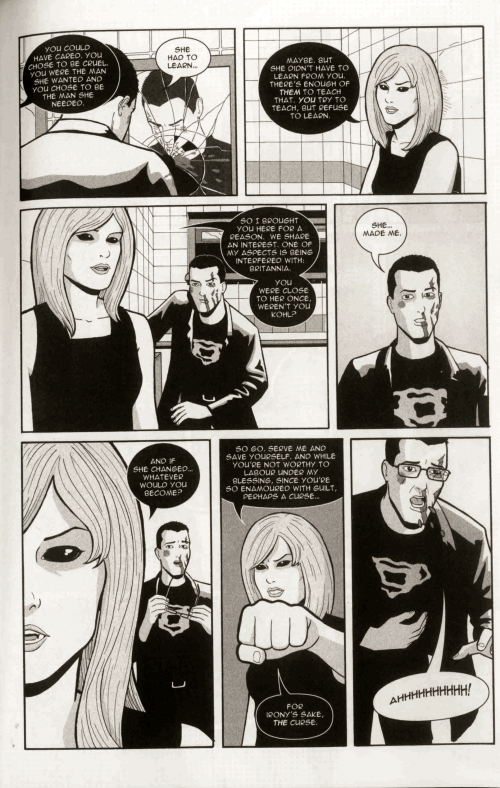

It is somewhat satisfying and fitting, then, that for the sin of being a huge dick, the narrator is cursed in a very feminine way:

Of course, this guy isn’t a Standard Edition Asshole Dick. He knows better, that’s the whole point. He might be using his love of Kenicke to pick up girls, but he also genuinely loves Kenicke. Summing up this contradiction, the essence of his fandom – the passion that defines him as a person and grants him music-related superpowers (more on this later) – is Britannia, a female avatar of British guitar rock. Not only that, but in a key scene we find out that in a contest between his girlfriend and Kenicke – sleep with the girlfriend, or get up to reset the needle on a Kenicke record? – Kenicke wins every time.

Let’s back up for a minute and talk about magic. In this metaphorical book, being a passionate fan of music gives you superpowers. So what’s the main character’s superpower? Well, he does “intricate vivisection rituals on pop songs to understand their totemic powers” (and then uses his powers for evil to seduce young girls, because he is a dick!!!) Beyond that, he can use Jedi mind tricks to get into shows for free

Let’s be real here – this is a much more useful and practical magic power than “flying” or “X-ray vision”, right?

In this book, we spend most of our time with Mr. Charming, so we never really see the other ways that “Phonomancers” channel pop music to enhance their personal power. That will be left until the next, more accessible book (in full color!), which I have already promised to discuss in the next article.

I’m not trying to say I have a unique insight on this comic, by the way. Any good ILM-er or diligent reader of British weekly music ‘zines would tell you the same, and the author does make many of these points for you. The feeling that I have unique insight is actually exactly what I share with the noxious asshole narrator. It’s this feeling of superiority and specialness, among other things, that he will have to kill to progress as a person.

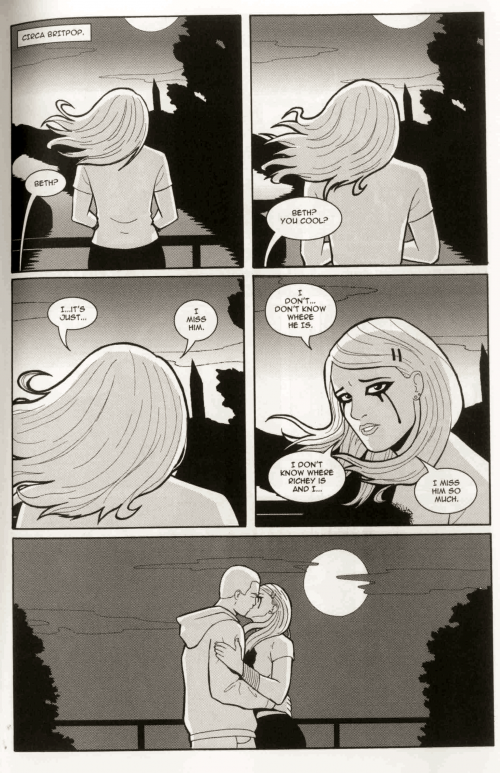

To show the seriousness of the situation, as the music press rewrites the past, the narrator’s memories actually start to shift. (The first clue that he is in an alternate, unacceptable universe? He is in the habit of listening to Echobelly records.) Besides the narrator’s personal hangups, we’re introduced to another character who was, at one point, heavily invested in a particular group, the Manic Street Preachers. While the narrator struggles to hold on to his sense of self, this Manics fan has actually split herself into two selves: a self that waits, wraithlike, for disappeared guitarist and lyricist Richey Edwards to return and reclaim his position as pop-music prophet. And another self, a “real” self, who no longer cares about music.

If you don’t know the specific groups under discussion, the scenes lose some of their power. There’s something universal about the idea that someone else is rewriting your past, though, and about investing so much of yourself in one thing, and being so badly hurt as a result, that you are never willing to invest so much or to care so much about any other thing again. And maybe Britpop club scene –> massive arena and festival tours is something any former indie kid – like for instance Hipster Runnoff‘s Carles – can relate to. Specific references, universal themes, in other words.

The rest of the volume is similarly metaphoric. The narrator goes on a spirit quest to save “the universe” (probably only his own universe) from the debasement of the discourse around Britpop. Some of these metaphors are clever:

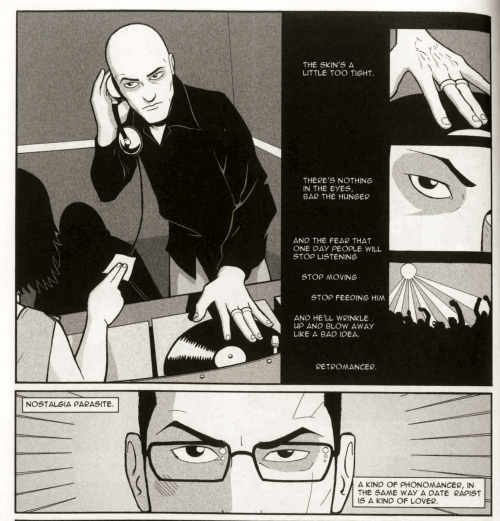

Retromancers as gollums, Gollum as junkie scum.

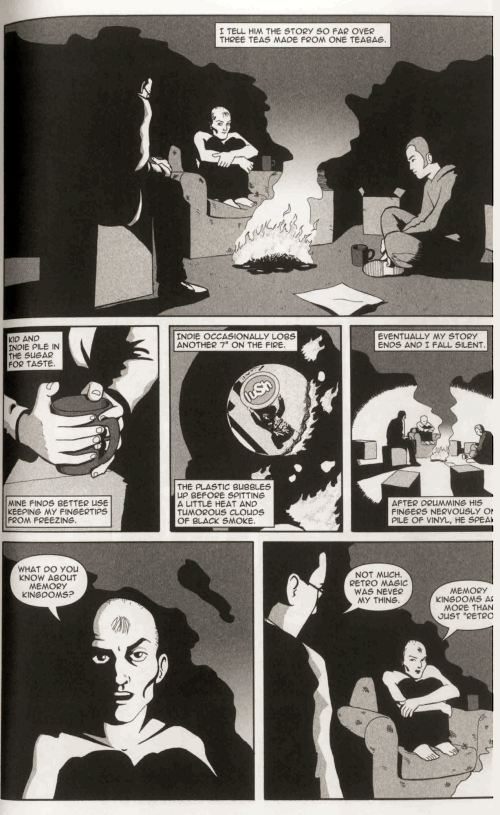

Throwing a vinyl record on the fire, and a discussion of “memory kingdoms” you can only enter if you’re not personally invested in them.

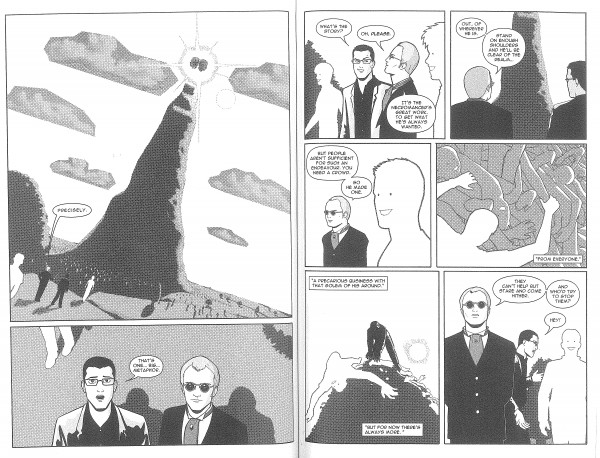

Knebworth Park in 1996, the huge festival headlined by Oasis, where – according to the press – countless individual fans lose all their distinguishing features and are transformed into just a mass, a crowd, a sales figure.

Sometimes, though, the pursuit of symbols and metaphors leads the author to strange places. An easy way to see this is to consider what happens when the “symbols” in his book are – not just real people – but still alive and working.

I don’t know that much about Blur, but I know enough to know that the automaton in these panels is not even close to being anything like the real Damon Albarn – either the person or the performer. How can you write about real people and not even care that you are completely misrepresenting them?

Kieron Gillen sidesteps this issue, somewhat, by setting all these scenes in a dream landscape. In his own mental cartography, which has been weirdly influenced by the media narrative around Britpop, Damon Albarn and Oasis are figureheads who are notable mainly for the roles they play in the media narrative. It’s the roles he’s interested in exploring, not the actual or perceived personalities of the performers.

Still, the author’s choice to focus only on roles is an odd one: if he cut his teeth as a music fan at small club shows, he must have met some of these people at some point, right? Is it because he’s a pop fan – in other words a fan of a genre in which the main relationship between fan and performer is necessarily mediated – that he thinks this way? Or is it just that Kieron Gillen has no interest in personalities outside of music (putting him in the minority of Britpop fans)?

But also, you know, the creator is dead, and all that.

And if you think about it, this privileging of the fan/critic perspective over the author/artist perspective is clear even in the premise (and title!) of the series: that being a passionate fan of music endows you with special powers. It was Sabina (once again) who pointed out that while you do see, by the end of The Singles Club, many different ways of being a listener-Phonomancer, what you don’t see are any musicians who are also Phonomancers. Can an artist be a Phonomancer in Kieron Gillon’s universe? Perhaps this question will be addressed in the forthcoming third volume of the series.

Speaking of dead authors, though – and those of you who would rather not know how the volume ends, please look away – it turns out that – shocker! – Britania has been dead the whole time. The retromancers feeding off manufactured nostalgia, the fans who arrived too late to be a part of the original scene (and probably wouldn’t have been cool enough to be there, anyway) – all of her later-day worshippers – are worshipping a corpse.

Was she dead all along – during Britpop as well? I honestly hope so. Otherwise, this whole narrative stinks a bit too much of pulling-the-ladder-up-after-you’ve-had-your-own-fun.

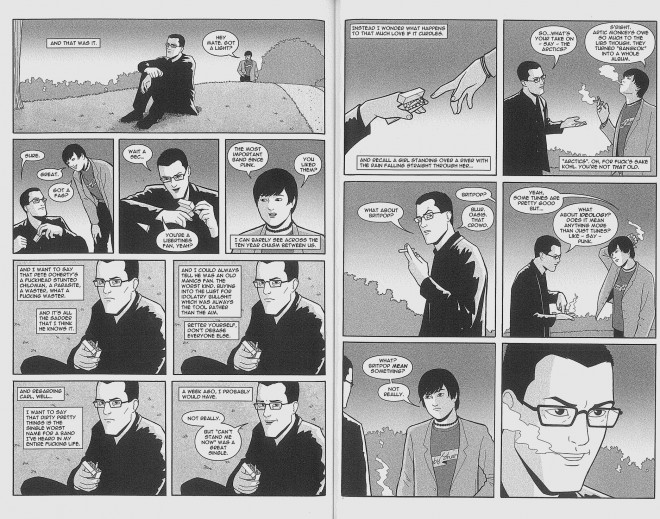

And this is where where I come in. Just before the narrator heads off on his final, quixotic quest to defeat the zombie ghost of Britpop and save the sanctity of his youthful soul from the cruel realities of crass commercialism, he meets a Libertines fan on a hill:

Click through for dialog if the text is too small too read.

Just like when he met the young Kenicke fan, he’s pretty sure that he understands The Libertines better than the Libs fan does. Unlike when he met the young Kenicke fan, though, he is now old, wise, and mature enough not to clutch this knowledge to his chest, as if his experience is the only valid one, and sneer down at the young fan. Instead he decides to fight for the fan’s right to keep his delusions.

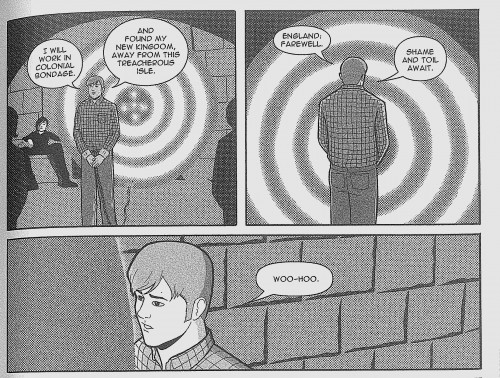

I’m just kidding. This is more about the narrator, an Old, making a conscious decision to relinquish his generation’s claim on the cultural cutting edge. The pop music zeitgeist belongs to the young, passionate, and idealistic.

It’s not a bad story to want to try to tell. After all, it’s not every day that you see this kind of “old must step aside to make space for the young” selflessness being valorized when it comes to pop culture. I think the last place I saw it was Les Mis, based on a story from the 1860s. At least in the US, the Baby Boomers seem to be too large, rich, and powerful of a marketing demographic for the culture industries to suggest that they should step out of the limelight.

While it’s awful nice of the narrator to make this gesture, it is weird that he doesn’t seem to consider that maybe the Libertines and their ilk – Arctic Monkeys, Klaxons, Kooks, Razorlight – do deserve to be considered Avatars of Britania’s Nth Coming. The Libertines, including Pete Doherty and Carl Barat (that co-frontman thing again), certainly thought of themselves that way.

But then you think: maybe Dude does have a point that each iteration of this meme will be more desperate and sadder than the last – as Sabina says, at least in Britpop Version 1.0 there were actual girls on stage, stepping out from their traditional roles as girlfriends and mothers and photographers and forum mods.

For the record, though, the Libertines were aware of the futility of reviving the past. “Queen Bodacea is long dead and gone/yet still the spirit of her children’s children children lives on” goes one of their most famous lyrics, about an ancient Celtic queen who lead a resistance against Roman invaders. (This line is second in notoriety only to their save-England-from-creeping-Americanization refrain, “No sadder sight than that/of an Englishman in a baseball cap”.) It’s a total fan cliché for me to quote lyrics, by the way, but I do it not to share a moto I ever adopted as my own – I’m American! How could I! – but as a way of demonstrating that Pete Doherty totally read the British weekly music ‘zines as a teenager, too.

The idea of taking up a spot in a lineage that is already gone is baked right into the premise of the band, in other words. So who’s to say that they are not an actual, authentic entry in that lineage – if you want to see it that way? And not just because the kids are passionate and naïve – as we all were once – and it therefore behooves the older, more jaded generation to step aside and to allow them to explore their romantic notions in peace. Rather, the reason they belong is that there’s no particular reason that dead-and-we-already-know-it-Britania can’t be every bit as real to the people who worship her as dead-and-we-have-yet-to-realize-it-Britania.

In fact, by assuming that the kids believe essentially the same thing he did – that they are participating in a vibrant underground scene not-yet-tainted by media narratives – the narrator proves, essentially, his own myopia. Even in the end.

This concludes Part 1 of my essay on Phonogram. Part 2 – featuring a sociological examination of pan-music-fandom message board ILM – to follow. I promise to talk more about Jamie McKelvie’s awesome art in the next post, too.