On Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Battlestar Galactica, et al.

On Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Battlestar Galactica, et al.

Here’s the problem with fiction. In fiction, there is evil. “It’s actual, like cement” (Philip K Dick, The Man In The High Castle).

Take Lord of the Rings. The premise of the trilogy is that ring is evil. Galadriel could try to use it for good; so could Boromir; it would corrupt them. The end. Sauron is irrevocably corrupted. There is nothing redeemable about him; there is no good left in him. The ring is evil and will inevitably turn you evil; there’s no question in the readers’ mind that it should be destroyed.

You can’t ever have that in real life. There is nothing that can turn you irrevocably evil, and no person who is pure evil. You can posit that there are sociopaths who don’t have . . . whatever you want to call it: a moral compass, human empathy, remorse, a soul. For the sake of argument, let us refer to the “soul,” with the understanding that it may not be a physical or even a mystical property. We may be simply referring to an idea that we impose upon our biological impulses and evolutionary development, an abstract that is an aspect of the larger abstract we call our consciousness or sapience, which allows society as we know it to exist.

“Evil” generally refers to those which lack this quality—“evil” people lack a conscience, compassion, or the ability to buy into the contract of human society. But even if those people exist, we can never say for certain who is one. Those who believe in the death penalty may say, “this person deserves to die,” and almost all of us may agree, “that person cannot function in society,” but none of us can actually look inside another human being and see if that thing, the soul, exists—not in the least because we don’t know what that thing is.

In fiction, however, you begin with a premise, and the reader assumes the premise is true for the universe of that story. The author can start with the premise that there is God, which means God exists in that universe. The author (not necessarily the narrator, who can’t always be trusted) can tell us there is evil, and there is. It is a fact of that universe, the way the existence of magic is a fact of Harry Potter’s world, the way vampires are a fact of Buffy’s, the way hobbits are a fact of Middle Earth.

This used to be what interested me about speculative fiction; it could be black and white. Lord of the Rings was not meant to be ambiguous. It is meant as an exploration of archetypes, of the heroic saga, of myth and religion. The premise that evil exists is a very simple and common basis for millions of stories.

And although it will never be like that in the real world, maybe that oh-so-clear delineation will help us make distinctions in real life. Maybe we can use stories like Lord of the Rings, where the evil is recognizable, to more easily see it in our real lives. Maybe we can use that story to understand that power can corrupt, that even the best of intentions can go awry. Maybe when we feel temptation towards a thing we are more likely to stop and consider whether there is evil in it.

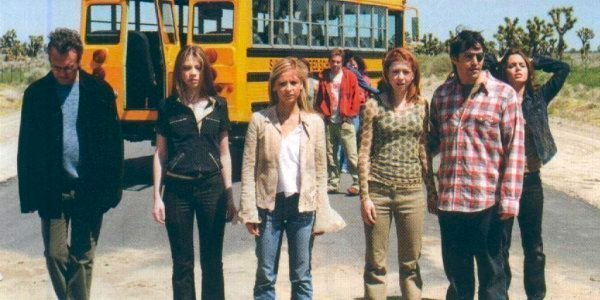

I started watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer for this reason.

I was in college and I had a horrible time there. I had few friends and I was very lonely, and I couldn’t read what I wanted because I had to read for class, and all of it was this Madam Bovary bullshit (sorry, Bovary fans) where everyone was morally reprehensible and I just hated everyone. The world then seemed gray, and what I really wanted was Lord of the Rings or Star Wars—black and white. Or even Independence Day. What I really wanted was to feel comfortable hating something, vampires or aliens or what have you, something I didn’t have to question.

Hello, Buffy. I remember thinking the first few episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer—the first time you see a vamp’s face go bumpy, the first time Giles said that the person inside was dead when you became a vampire, the first time Buffy explained vampires were just demons—that this was exactly what I needed.

The premise of Buffy… in the beginning is that vampires are evil. It’s a fact of the universe, like the evil of the ring is of Lord of the Rings, like superpowers are in superhero comics, like vampires exist. It’s black and white. Good and evil. Old fashioned ass kicking.

And then morally gray stepped onto the scene.

Angel provides the morally gray, where not everyone who is a vampire is evil and should be killed. Angel proves that vampires aren’t just demons, with no vestige left of the human that inhabited the body. Angel proves that vampires are the evil in us all.

Angel asks the question of who we are and what we are capable of. Angel is the temptation toward evil, and also the love and hope that holds us from the brink of it. Angel plays the role of both Gollum and Frodo. (Except he’s taller. And wears a swirly coat.)

And yet, as with Lord of the Rings, black and white can be pretty firmly delineated when it comes to Angel—or at least, Joss Whedon, the writers, to some extent the text would like us to believe that. Angel has a “soul.” That’s why he’s different from other vampires. The other vampires are still evil and should be killed—no moral conundrum there.

We, the viewers, are familiar with the word “soul”, and so immediately define “soul” as compassion, conscience, what it takes to be functional in society, etc—however we have defined that word in the past. As for how the soul is defined by the show, the only working definition we are given is “power of choice.”

Once Angel loses his soul, the implication is that he is incapable of behaving any other way than evil, or that he is capable but does not desire it. When Angel does have the soul, he still has the same evil impulses, but he desires to be a better man, and is capable of behaving as one. Therefore, the one definable thing that has been taken away from him is the desire or ability to act differently—the ability to choose.

Therefore, according to the premise of this universe, the soul includes the mechanism by which we choose. Vampires cannot choose to behave as they would if they did have that thing—the soul. And without that thing, they are evil. It is morally acceptable, even necessary, for Buffy to slay them. It’s the premise of the story. The show has given us what appears to be black and white to work with.

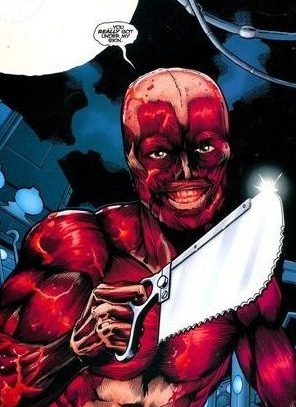

Enter Spike.

At the end of season six, Spike goes to Africa and earns his soul back. Later, the show suggests that he did not choose to get a soul, that he thought he was getting a chip in his brain removed when he went to Africa. The text does allow for the possibility of this, and in doing so, the text is allowing for a vindication of Buffy, Angel, and the fact of black and white.

I.e., if Spike doesn’t choose to get his soul back, we accept the premise that was given to us by the creators of this universe: vampires cannot choose. Angelus cannot choose to be a good man, which exonerates Angel for Angelus’s (soulless Angel’s) behavior. We can also exonerate Buffy for slaying all those vampires.

But if Spike did choose to get his soul back, the metaphysics of this universe are actually different than we have been led to believe. If Spike can make the choice to earn his soul, then the definition of soul is not choice. It means any vampire can choose.

Yes, Spike had special circumstances. Yes, Spike’s a special guy. He’s a unique and beautiful snowflake and his love for Buffy is epic and pure. Maybe he’s the only vampire in the history of ever who would ever choose to earn his soul. But the point is, if Spike chose, then the premise of the universe does not include the fact that a vampire can’t choose. And if a vampire can choose, he can have a soul. And if he has a soul, he’s not evil—by the laws of this universe.

Where this really gets ambiguous is Buffy. If Spike did choose his soul, then the viewer doesn’t know what vampires are capable of either, or why they are the way they are. There is not metaphysical fact given by the premise of the show about what a vampire really is, what a soul really means, what a vampire is capable of. Because those facts are not given to use by the authors of this universe, we know no more about vampires in this universe than we do about human beings in our own. How, then, are vampires different than human beings? Does this make Buffy a murderer? What do we with vampires? Is slayage the only option?

What I would have appreciated from Buffy the Vampire Slayer is those questions being asked.

I’m not condemning Buffy Summers. Vampires rape murder pillage kill and eat the babies, and those are evil things. And for the most part, vampires are not Spike; they will not choose to earn back their souls. Also, they need blood to live. This, uh, is how they are different than human beings, and personally I have no idea whether murder would be a better answer than letting serial killer terrorists run amok. What I want is not for the show to tell us Buffy is wrong, but for that question to be asked.

The show does ask plenty of times if Buffy is wrong, but it’s never about slaying vampires. The problem is that the evil of vampires was the premise, remember? The story isn’t really about the villains, except for the exceptions that prove the rule.

Instead, this story was supposed to be a story about humanity, humanity struggling in the face of adversity, an undefeatable foe: evil. Lord of the Rings is not about whether the ring should be destroyed; the readers know, and Frodo knows: it must be destroyed. What the story is about is about how difficult it can be to do the things we know must be done; how much we long to give in. Doubt lies not in the duty itself, but in our ability to carry out the duty.

In Buffy the Vampire Slayer, slaying is supposed to be the same way. We’re never supposed to doubt that someone must slay. We are only meant to empathize that the call of slaying must lie with her, the sacrifices she must make in order to do it.

That’s why the writers/creators made Spike’s “choice” ambiguous. They did not want to deal with the consequences of changing the entire premise of the show. They did not want to go back and question every single thing Buffy had ever done, every vampire that died at her hands. They did not want to go through the trouble of really defining “soul”, or tear down everything they had built with Angel. They didn’t want to sully their black and white.

Who would? That would be a lot of work.

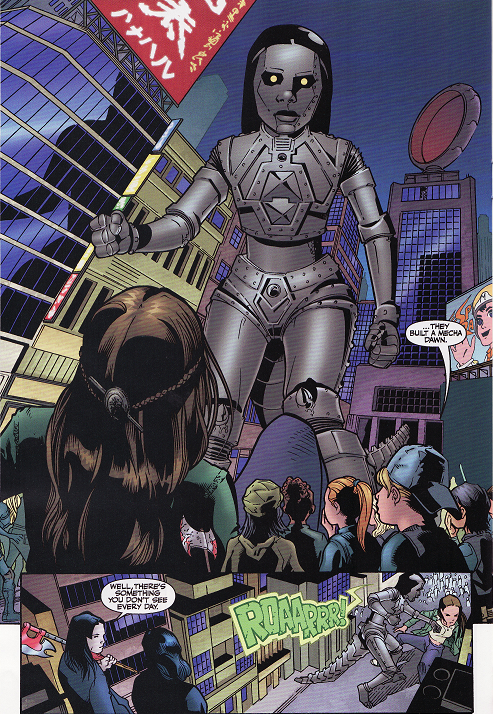

Battlestar Galactica, that’s who. Maybe the creators planned from the beginning to make us question whether the destruction of Cylons is actually murder. If they did, they didn’t quite let the viewers in on it from the beginning. (Even though the Cylons, er, “had a plan.”)

The premise for the show in the beginning, despite the Cylons’ pretensions to godliness, is that the robots are evil. This makes sense instinctively, because instinctively we feel that robots are soulless. When we talk about “soul” we’re talking about humanity. Even if we think of it as biological fact, as I do when I say that it’s an idea applied to biological and evolutionary impulses—well, robots aren’t biologic, and didn’t evolve. Robots don’t have souls. Robots are evil. It’s a fact.

Boomer, of course, is the initial exception; she is a Cylon, a robot, but she isn’t like the rest. All the other robots killed all the rest of humanity, but Boomer wasn’t a part of that. She doesn’t know she’s a robot; she feels like a human. That makes her different.

If this seems like twisted reasoning, it is. It’s also fairly typical. The recipe for your awesome Good Versus Evil fiction is to have a Big Bad, and then a Big Bad’s Henchman or Turncoat who provides the morally gray. Gollum, Darth Vader, Snape and/or Draco, Angel. I could go on, but really I’m working with the broadest of broad references, here.

We recognize the truths Gollum and Angel gives us—evil is not in just some entity completely outside ourselves. It is within us all. Luke could become Anakin, if he did not resist at the crucial moment. Frodo can become Gollum; Harry can become Voldemort, and we could all be Boomer. What we must do is use our “soul” to resist the force of evil.

But over the course of the series, Battlestar Galactica becomes less and less about resistance, and more and more about understanding the Cylons. The Cylons almost destroying the human race, then hunting them down, then enslaving them in order to live peaceably with them, then sequestering themselves away from them, then returning to work together to find an Earth we can live on in peace is very much how more than one race of humans has behaved in the past.

And somewhere along the line, we have to ask that question again: what separates us from them? We assume at the beginning of the series that humans have a soul and the robots don’t, but as the pieces unfold, it becomes clear that nothing is so clear. We still don’t know what a soul is; we don’t know how to say who has one. We don’t know what evil is, or if it exists. The creators of this universe does not make evil the premise of this universe—or, actually, they did, and tore it down, revealing that absolutist constructs are part of the problem.

What juxtaposing these two shows against each other does for me is show something lots of mainstream speculative fiction does—even somewhat laudable fantasy, such as Buffy—versus what almost no mainstream speculative fiction does—except Battlestar Galactica, and other key exceptions. A lot of mainstream speculative fiction these days is constructing morally absolute circumstances, waving a hazy hand that suggests there might be morally gray somewhere, and in the end, the bad guys die, the good guys win, the end.

Of course, I am using the term “mainstream” loosely. The most popular show on television is still (I think?) American Idol—which, I suppose, one can argue broaches all kinds of questions about morality and evil, but frankly I’m not equipped to approach such questions. And speculative fiction has always had a very large corner on addressing questions about moral absolutism and relativism, the definition of humanity, the composition of the soul and the quality of mercy—and the very best of speculative fiction does so very well.

However, it is impossible to deny that even just the last decade or so has seen a remarkable increase in popularity of speculative fiction, which is noticeable in particular on television and the big screen. As a fan of speculative fiction myself, I’m pretty happy about this, but find myself considerably disappointed by the handling of questions that are so often central to speculative fiction.

We could talk now about the moral obligation of art, but I do think a purpose is served through beauty. Beauty can make as much a difference in someone’s life as asking them to question can. Sometimes, beauty itself is purpose enough; asking beauty to serve any other purpose than to be beautiful misses the one truth we know for certain above all in this existence. We don’t know why we’re here, or what we should do, but we know this truth, and it is both heart-rending and full of joy: we are.

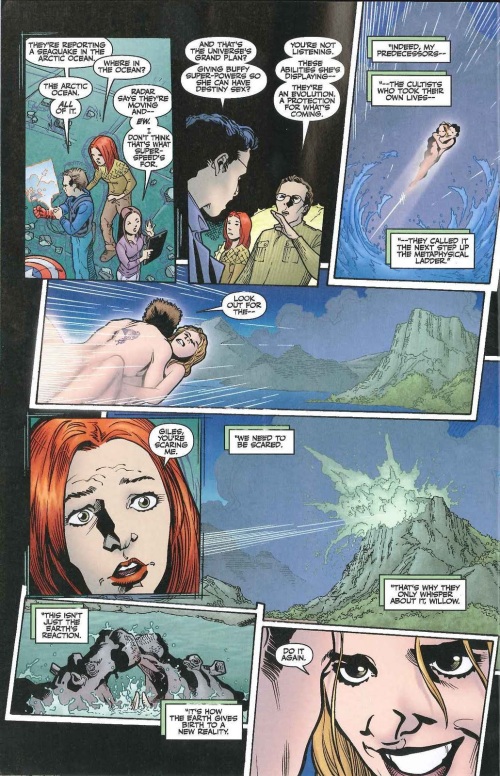

The model of good versus evil in literature isn’t wrong. It seems that there is a tradition in literature, of which the Christian Bible is just one element, of this good versus evil, black and white, Joseph Campbell’s heroic journey. Lord of the Rings and Star Wars are purposeful reflections on this tradition, explorations of an essential story which resonates deeply within us all, or said story would not have survived so long. Exploring this tradition and continuing to riff on it is vital, I think.

But I also think it is vital to question this tradition, and to find out with what inside us it resonates. There are stories which use the binary model and then break it, and we need those stories too.

Of course, there are plenty of stories that don’t even reference that model. All modern literature has gone morally gray. Hello Madam Bovary; where have you been? Post-modern literature is even more bleak than modern, and no doubt contemporary literature is even more bleak than when I was reading Flaubert. But I think there’s something to be said for stories that set up the binary and then proceed to tear it down, especially now, because of the preponderance of the binary—not just in literature, but in current thinking, politically and culturally.

We all long for some form of escape, from time to time, and for some of us that means absolutism, or worlds where evil is actual, like cement. There are some very loud voices saying, “No, you have it all wrong!” to those who would apply such absolutism to our world. At times it can be more effective—both in literature and real life—to say, instead of, “That world does not exist”—

“We live in your world full of cement. We walk upon it; we live within it; we eat it; we breathe it. I understand it as you do, and yet, of a yellow evening, walking down the street, there’s a strange taste in my mouth—it tastes like dust. I eat dust. I live dust; I walk on dust, and look down to find that the cement is a fine powder, and I have breathed it in, and so have you. And then I look around me, and see that the world of cement doesn’t exist at all.”

It never did.