The idea for this paper began when I noticed a pattern in a series of superhero films that I was showing to a recent class devoted to the genre. Whether it was the 1978 Richard Donner Superman film, the pilot of the 1970s Wonder Woman television show, the 2002 Sam Raimi Spider-Man, or the 2008 Christopher Nolan Dark Knight, superheroes are repeatedly asked to make a “sadistic choice” (to quote the Green Goblin) between two equally unpalatable options. In the case of Spider-Man, he must choose to either save Mary Jane Watson from being dropped off of a New York City Bridge, or to save a tram-car full of children from the same fate. Superman must save Lois Lane or Hackensack NJ from being obliterated by a cruise missile. Wonder Woman must save either Steve Trevor or Washington DC from death-by-Nazi, and Batman must save either Harvey Dent or Rachel Dawes from the Joker’s explosives. As the Goblin notes, these choices seem designed to define the heroes, and heroism itself. Will they make the “selfish” choice that benefits them directly, or the more “selfless” choice that benefits the greater good.

These choices seem to advance the familiar superheroic dictum, “with great power comes great responsibility,” suggesting that super powers make people necessarily more responsible to others and that “heroes” must abandon their own selfish interests for the good of the many. In fact, however, these scenarios most often emphasize not the burden of great power, but the ways in which great power alleviates the hero from responsibility. In almost all of the examples mentioned above the hero is never actually forced to make a choice. Rather, Spider-Man, Superman, and Wonder Woman are all able to triumph over time itself and save both parties. It is my goal in this paper to indicate the ways in which this exercise in simultaneity provides a useful metaphor for the ways in which superhero comics, particularly those by mainstream publishers, treat matters of diversity. Rather than shouldering the ethical burden of social, political, and temporal “progress,” Marvel and DC more often attempt to have things “both ways,” retaining a troubling embrace of white male hegemony, while simultaneously introducing more diverse characters and storylines, without ever admitting that these two ends may be mutually exclusive. These companies, like their heroes, seem unwilling to “progress” temporally, or ethically, particularly in terms of race, class, and gender equality, despite initial appearances to the contrary.

Part and parcel of this problematic, as mentioned, is the fact that the scenes described deny temporal progress in multiple ways. First, each scenario presents a fundamental spatiotemporal impossibility, the idea of being in two places at the same time. The Superman film acknowledges this most clearly when Lois is initially killed by the missile, prompting Superman to reverse the Earth’s rotation, improbably turning back time and saving her life. More metaphorically, the Spider-Man film also “turns back the clock” and brings the hero’s lover back from the dead by restaging the comic-book death of Gwen Stacy, which occurred some thirty years previous in Amazing Spider-Man #121 (1973). In the comic, as in the film, the Green Goblin hurls Peter Parker’s love interest from a NYC bridge. In the comic, however, Spider-Man is too late to save her. The film Spider-Man, then, succeeds not only in saving Mary Jane and the children, but also in metaphorically traveling through time to save Gwen Stacy. The fantasy of power in play in this alternate continuity, or “forking path,” is a fantasy of overcoming the progression of time and therefore overcoming mortality itself. Concomitantly, it is a fantasy in which ethics are not asserted, but abandoned.

As Jean-Paul Sartre, in particular, and existentialist philosophy in general, remind us, our identity and our ethics are only a compilation of the choices we freely make dynamically in time. If we do not have choices, we have no ethics. Indeed, near the outset of “Existentialism is a Humanism,” Sartre also discusses a “sadistic choice.” He tells of a “boy” he knew, who “was faced with the choice of leaving for England and joining the Free French Forces…or remaining with his mother and helping her to carry on” after the death of her other son (24). Sartre uses the example to explain the ways in which “we are condemned to be free” (27) and to insist that our choices will define us. We do not make our choices on the basis of a ready-made system of ethics, argues Sartre. Rather, ethics are made only through choices. “In creating the man that we want to be, there is not a single one of our acts which does not at the same time create an image of man as we think he ought to be” (17). Similarly, the film Green Goblin functions as a surprising Existentialist when he tells Spider-Man, “We are who we choose to be,” emphasizing the ways in which heroism, ethics, and identity are a matter of choice. In my initial examples, however, and quite frequently, superheroic power involves not the power to make choices, but the power to avoid them. Here, Superman and Spider-Man need not choose between their love interest and a broader catastrophe. They instead save everyone involved, denying the basic relationship of cause and effect, and therefore of ethical responsibility.

In the 1962 essay “The Myth of Superman,” Umberto Eco articulates the ways in which mid-century Superman comics operate in an “oneiric climate” that involves a basic denial of temporal progression, and therefore of mortality, and of ethics, citing Existentialist thinkers like Heidegger to make the link. Like Sartre, Eco notes that the “existence of freedom, the possibility of planning….[and] the responsibility it implies” all depend upon temporality (156). However, subsequent critics like Charles Hatfield and Henry Jenkins have argued that the introduction of “continuity” particularly to Marvel in the 1960s served as a rebuttal to Eco, pointing to the ways in which events in continuity did have consequences and therefore could serve as a meditation on ethics, morality, and social progress. Indeed, Gwen Stacy’s death is one of the most obvious examples of “events with consequences,” and therefore, as Ben Saunders illustrates brilliantly in his book Do the Gods Wear Capes? it serves as an event that can teach both Peter Parker and his readers important truths about ethics, about cause and effect, and about the real possibility that we will never be powerful enough to overcome mortality, nor good enough to avoid tragedy.

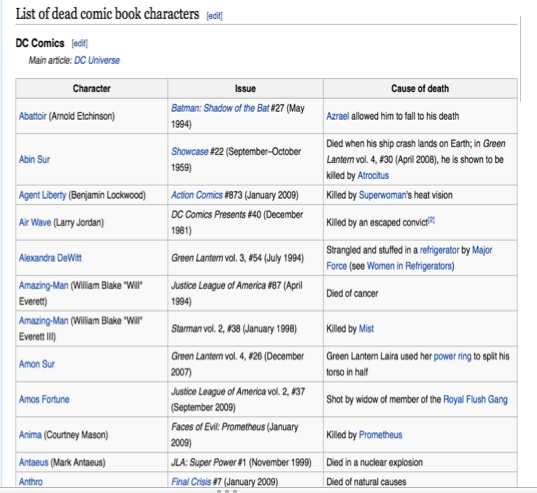

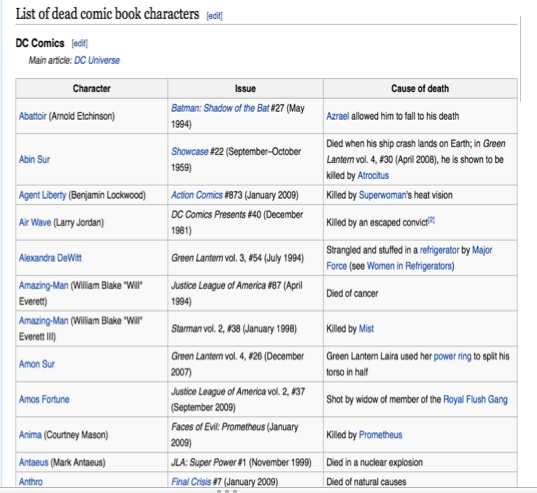

Certainly, continuity, and even death, remain, even now, as central components of the Marvel and DC universes. Events do occur month after month, and these events do seem to have consequences, resulting in the births, deaths, marriages, and separations of heroes and/or their enemies, companions, lovers, and acquaintances. It is worth noting, however, as Marc Singer does, that rarely, if ever, are these consequences permanent. Superman, after all, has died and come back to life, as have Green Lantern, Green Arrow, Phoenix, Batman, Captain America, and a slew of others, helpfully chronicled by Wikipedia’s extensive chart of dead and resurrected characters. Superman and Spider-Man have both been married and now are not (though neither has been divorced). Spider-Man has graduated high school and been returned to it in at least three different alternative realities. These events happen both “in the continuity” of the basic Marvel or DC universes and in “alternative continuities” in the comics and other media like video games, television shows, and movies, all of which continually elaborate new paths forking outward from the temporal “nodal point,” what David Bordwell calls an “intersection,” from which they begin. The “Imaginary Stories” of the 50s and 60s cited by Eco have been superseded by Marvel’s “What If” tales, DC’s Elseworlds, periodic reboots of standard continuity, the Ultimate Universe, and etc. There is no fan of superhero comics and/or films that is not versed in the idea of multiple realities, and, indeed, Henry Jenkins notes that the age of strict continuity was very brief, if it ever truly existed. He argues that there has been “a shift away from focusing primarily on building up continuity within the fictional universe and towards the development of multiple and contradictory versions of the same characters functioning as it were in parallel universes” (“Just Men”). As a result, like their own characters, the editorial staff of Marvel and DC never have to live with the ethical and material consequences of decisions they make about characters and worlds. Instead, time can be rewound, universes rebooted, and/or alternatives created, allowing mutually contradictory outcomes to coexist, just as they do when Superman both fails to save Lois and rescues her.

In this way, contemporary comics resemble a series of thought experiments of the “What If” variety. “What if” Superman died? (an eventuality played out both in a 1950s “Imaginary Story” and in the 1992 in-continuity comic adventure)? What if he didn’t? What if Aunt May died? What if the woman who died was just an actress playing Aunt May? What if Gwen Stacy came back as a clone? While these perpetual reboots and alternative explorations are both frustrating and delightful to fans, the provisional nature of all superhero adventures denies any kind of permanent consequences.

What then, if anything, does this have to do with questions of diversity? Though Marvel and DC have been introducing racially diverse characters to their superhero universes since the 1960s, in the past few years, such efforts have increased dramatically, and have been widely celebrated in the popular media. Certainly, this increase in attempts at diversity is preferable to the alternative. But the reliance on the structure of multiplicity as opposed to continuity limits the impact and suggests the ways in which comic book companies (and perhaps their primary fan base) are willing to accept diversity only up to a point, as long as it requires no sacrifice of privilege on the part of hegemonic interests.

It is worth recalling, in this regard, that the superhero idea is a variation on the notion of the übermensch, popularized by Nietzsche in Thus Spake Zarathustra. The übermensch itself is tied to the idea of racial Eugenics, a discourse that imagines an ideal human being as a blond-haired, blue-eyed hyperintelligent white man to be achieved through selective breeding. Early proponents of Eugenics opposed immigration by “lesser races” and were, not surprisingly, anti-miscegenation. The quest to become “ideal” or “super” was then, in many cases, the quest to become “whiter.” As critics as diverse as Gershon Legman and Chris Gavaler have noted, the Ku Klux Klan is not far removed from the idea of superheroes, masked men embodying and protecting white male privilege by rooting out the alternative through violence. A true transformation, then, of the superhero concept along the lines of racial, gendered, or sexual egalitarianism would need not only to introduce characters and heroes of different backgrounds, but to challenge the notion of white male heterosexist supremacy. It would have to make a choice between white patriarchal heterosexual privilege and actual equality.

Unfortunately, as I have articulated above, contemporary comics are not designed or inclined to pursue this kind of choice. As in other matters, diversity is almost always presented in the form of a “What if” question. What if, for instance, Spider-Man were black? This thought experiment is explored through the character of Miles Morales in the Ultimate universe. Interestingly, in this timeline Peter Parker dies in order to pave the way for Miles’ ascension to superhero status. In a vacuum, of course, this turn of events seems to dynamically symbolize the exact scenario I suggest. If Peter Parker is a symbol of white privilege, then perhaps his death is a symbol of the sacrifice of the privilege that must occur if true equality is to be achieved. However, “Ultimate” Peter Parker is only one “forking path” and, in fact white, straight, male Peter Parker remains as Spider-Man in the primary Marvel Universe. In truth, Marvel is not willing to sacrifice white male power and privilege for the sake of diversity. Instead, diversity here becomes a consumer option that requires no sacrifice of another more common to the superhero idea, that of white supremacy.

Similarly, “Wwhat if Superman were black” has been answered in multiple contexts, none of them challenging the primacy of white male Clark Kent. In 1992, John Henry Irons was introduced as Steel, briefly replacing Superman while he was dead. When white Superman returns, however, Steel becomes a secondary or supporting character, indicating the ways in which DC, like Marvel, is unwilling to entertain the notion of the sacrifice of white power and privilege for the sake of diversity. Another black Superman, Calvin Ellis, is President of the United States in an alternate, secondary continuity. Again, what exists here is not temporal, social, or political “progress” in time, but the willingness to view space-time as a series of forking paths, where any spatiotemporal “intersection” can be revisited and followed without sacrificing any other path, regardless of its troublesome politics. Likewise, John Stewart, James Rhodes, and Sam Wilson are introduced to answer the question, “What if Green Lantern, or Iron Man, or Captain America were black?” In all cases, however, even though these shifts have occurred “in continuity,” the emblems of white power and privilege that are Hal Jordan, Tony Stark, and Steve Rogers return to their original roles (or will), displacing their African-American counterparts into subsidiary ones.

Woman superheroes often undergo similar fates, as the dual questions of “What if Gwen Stacy had lived?” and “What if she were bitten by a radioactive spider?” can both be explored in the alternate universe Spider-Gwen. Likewise, the recent turn to the idea of “Thor as Woman” will seem progressive until Thor the man returns to the role (likely keeping the female Thor as an alternate or subsidiary character). In this, as in the above examples, the typical strategy, is to create separate but “unequal” universes, timelines, or comics magazines, just as separate but unequal schools, bathrooms, hotels, and drinking fountains were created in the aftermath of Plessy vs. Ferguson and in the Jim Crow south. Obviously, the results are far less important in the world of formulaic genre fiction than they were in real historical circumstances, but it is worth noting the ways in which “progress” here is rejected in favor of marketing “alternatives.”

In his reading of “multiple draft” or “forking path” films like Sliding Doors, Run Lola Run, and Groundhog Day, David Bordwell notes that in almost all such films, though multiple alternative narratives are presented as emerging from one spatiotemporal “intersection,” (“What If”) the director is careful to “mark” one narrative as the correct, “real,” or “authentic” path. For a conventional single narrative, Bordwell, argues, it is always the final path that “we take…as the correct one” (“What If”). In serialized and multiple narratives wherein there is no “final” version, it would seem, as Karin Kukkonen posits, that there would to need be no “baseline reality” or preferred version. In truth, however, and particularly in regard to diversity, there is, as Marc (qtd. in Duncan, Smith, and Levitz 214) has argued, a preferred “state of grace” for iconic characters, a constellation of historical, physical, and personality attributes that are deemed authentic by creators and fans, even if no currently functioning “version” of the character fulfills them all. In the case of the heroic pillars that mint cash for Marvel/Disney and DC/WB, part of the superheroic “state of grace” seems to be, in most cases, whiteness, masculinity, and heterosexuality. Certainly, there are characters whose “authentic” identity is black, or female, or even gay (or all three), but the economic and symbolic flagship heroes of Marvel and DC are white men who still serve the symbolic function of the übermensch, an ideal founded on notions of white power and privilege that are diametrically opposed to ideals of diversity and equality.

While Steel exists as an independent character, he was also introduced as a decidedly “inauthentic” Superman to be shoved aside upon Clark Kent’s inevitable return. While John Stewart has played the role of Green Lantern for years at a time, both in the comics and on an animated television series, Hal Jordan repeatedly returns as the “one true Green Lantern” (despite his death) both in the comics and in a failed blockbuster Hollywood film. Tony Stark/Robert Downey is the white hero who fights brown terrorists in the Iron Man film franchise, while Rhodes is a faithful friend and sidekick. Blond-haired blue-eyed Steve Rogers roams the movie screens even as he has been momentarily displaced/replaced by Sam Wilson in the current comic book series. In the Marvel Universe, it is always Rogers who is the “authentic” Captain America, the perfect representative of the white male heterosexual privilege that is America, whether we like it or not.

On one hand, it might be seen as laudable that comics companies, like their heroes, wish to “save all parties,” refusing to sacrifice their iconic heroes even as they attempt to introduce alternatives. At the same time, ethical decisions are predicated on sacrifice and difficult choices. Alternative continuities and reversible temporalities allow comics companies to avoid those choices. In fact, in clutching so tightly to nostalgia for the middle part of the twentieth century, when most of their heroes were created, they, like Superman, show a perhaps buried desire to spin the Earth backward upon its axis to a time when Jim Crow ensured the white power and privilege that superheroes exemplify. Likewise, it takes us to a time before second-wave feminism or the gay rights movement. While it is perhaps understandable that Superman does not wish to sacrifice Lois in order to save strangers, at long last white male America should be willing to sacrifice our own power and privilege, rather than constantly revisiting and rebooting it, while retaining more diverse alternatives only provisionally and without any permanence. As the Green Goblin says, “We are who we choose to be,” and as long as we choose to privilege white power, and to refuse temporal, social, and political progress, we should not be congratulating ourselves on a provisional, temporary, and, yes, marginalized, turn to diversity that functions primarily as niche marketing. Perhaps questions like “What if Ms. Marvel were a Muslim” and “What if Batwoman were a lesbian” are the beginning of a more egalitarian comic book world, but it can only be a beginning if we are willing to progress forward in time from there.

Bordwell, David. “What-If Movies: Forking Paths in the Drawing Room.” Observations on Film Art. http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog.

___. “Film Futures.” Observations on Film Art. http://www.davidbordwell.net/books/poetics_06filmfutures.pdf

Duncan, Randy, Matthew J. Smith and Paul Levitz. The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture. 2nd edition. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Eco, Umberto. “The Myth of Superman.” Trans. Natalie Chilton. 1962/1972. Arguing Comics: Literary Masters on A Popular Medium. Eds. Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2004. 146-64.

Gavaler, Chris. “The Ku Klux Clan and the Birth of the Superhero.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 4.2 (2103): 191-208.

Hatfield, Charles. Hand of Fire: The Comics Art of Jack Kirby. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2012.

Jenkins, Henry. “Just Men In Capes.” Confessions of An Aca-Fan: The Official Weblog of Henry Jenkins. http://henryjenkins.org/2007/03/just_men_in_capes.html.

___. “ ‘Just Men In Tights’: Rewriting Silver Age Comics In An Era of Multiplicity.” The Contemporary Comic Book Superhero. Ed. Angela Ndalianis. New York: Routledge, 16-43.

Kukkonen, Karin. “Navigating Infinite Earths.” The Superhero Reader. Eds. Charles Hatfield, Jeet Heer, and Kent Worcester. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2013. 155-69.

Lee, Stan and Gerry Conway, writers, Gil Kane, penciler, John Romita, Sr., penciler and inker, Jim Mooney and Tony Mortellaro, inkers. Amazing Spider-Man: Death of the Stacys. New York: Marvel Worldwide, Inc., 2012. Originally published as Amazing Spider-Man #88-92 and #121-22, 1970-73.

Legman, Gershon. Love and Death: A Study in Censorship. 2nd edition. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1949/1963.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism and Human Emotions (often published as Existentialism is a Humanism.) 1957. Trans. Hazel Barnes. New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1990.

Saunders, Ben. Do The Gods Wear Capes?: Spirituality, Fantasy, and Superheroes. London: Continuum, 2011.

Singer, Marc. “The Myth of Eco: Cultural Populism and Comics Studies.” Studies in Comics 4.2 (2013): 355-366.

Spider-Man. Dir. Sam Raimi. Perf. Tobey Maguire, Kirsten Dunst, Willem Dafoe. Sony, 2002.