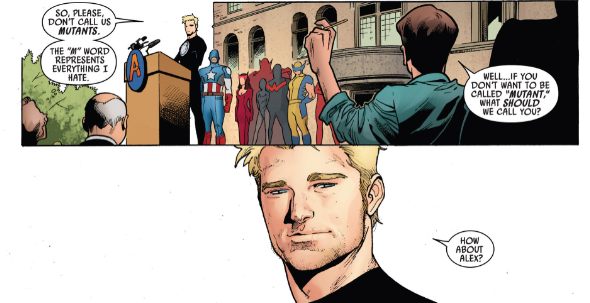

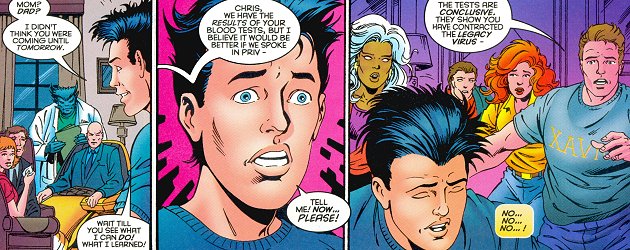

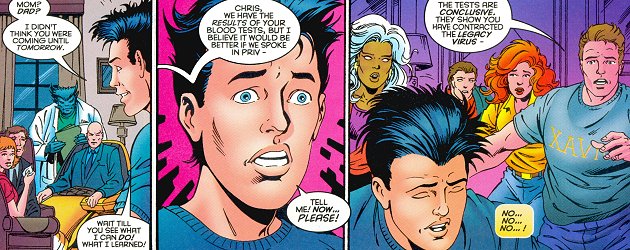

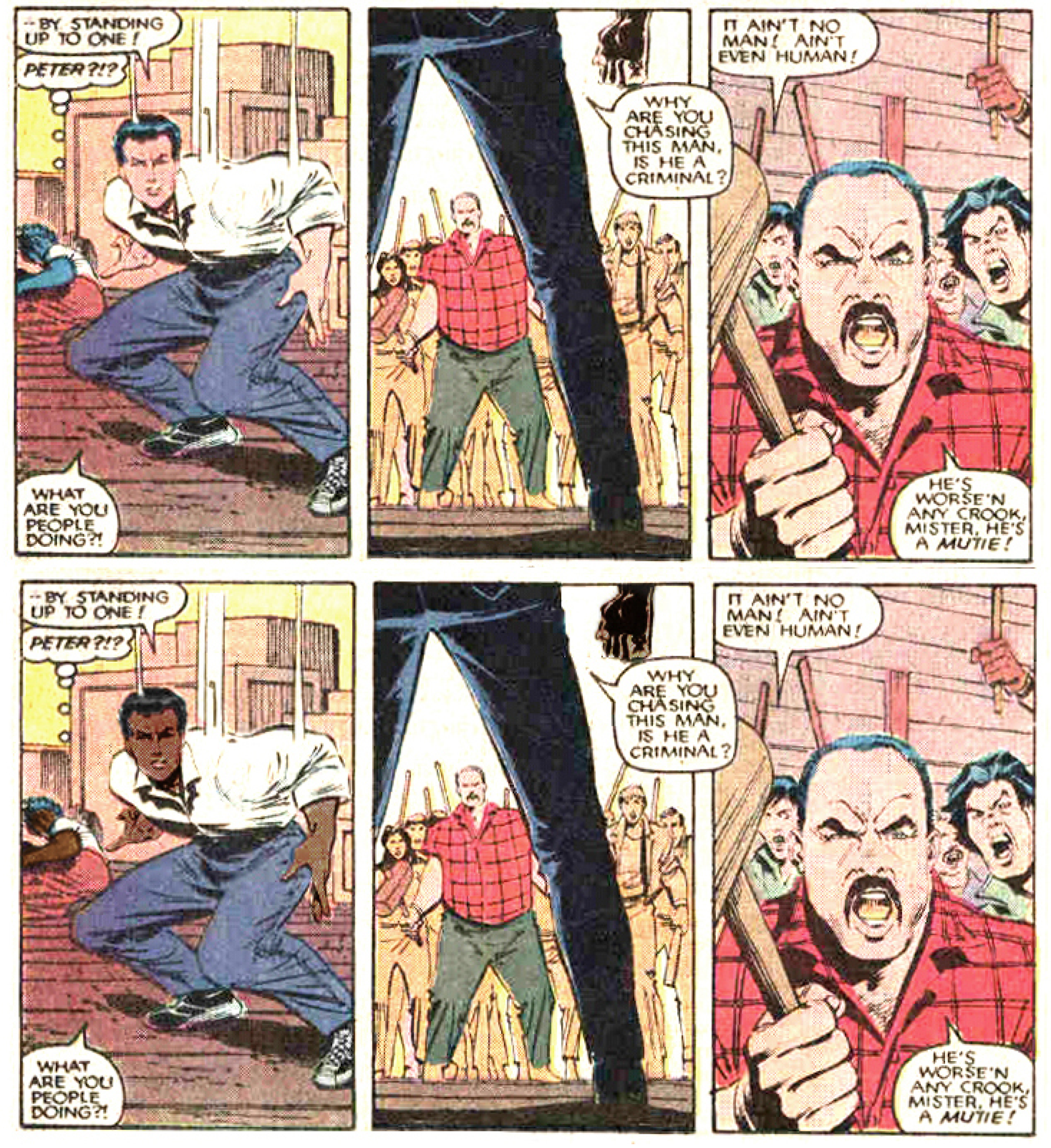

An edited image from the series X-Men of Color.

“The X-Men are hated, feared and despised collectively by humanity for no other reason than that they are mutants. So what we have here, intended or not, is a book that is about racism, bigotry and prejudice.”

Longtime X-Men writer Chris Claremont

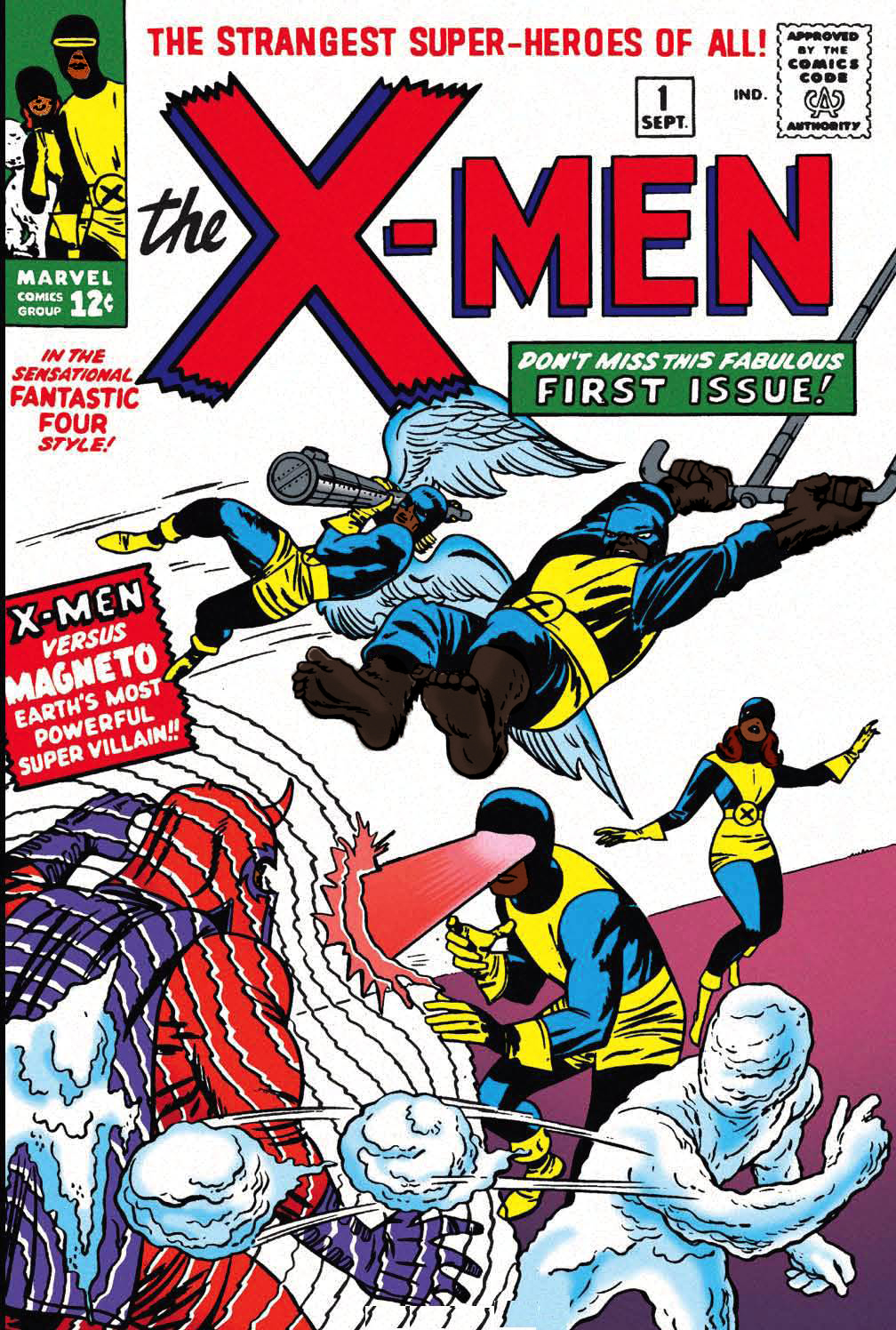

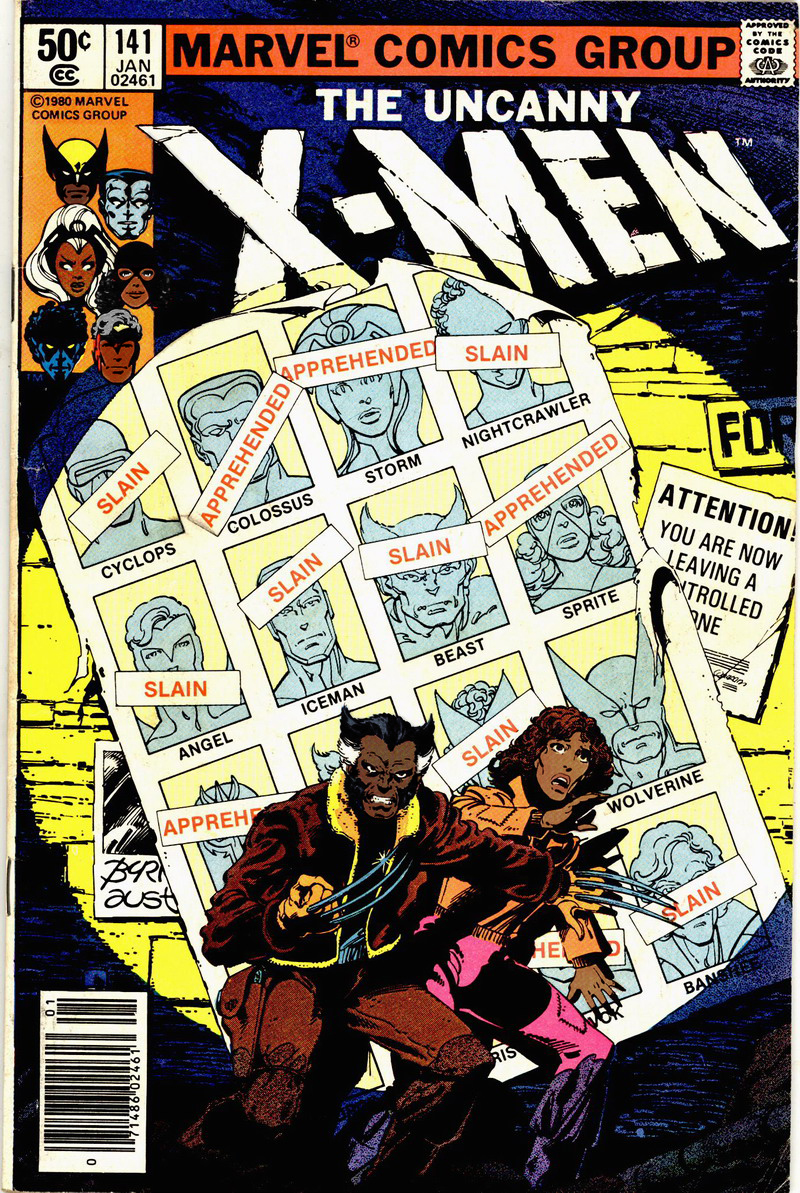

Imagine a work of fiction that focuses on the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s except that in this work, white men have replaced all of the people of color. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X both have white stand-ins and white followers. In fact, almost all of the characters are white men. It may seem bizarre, but this is the X-Men.

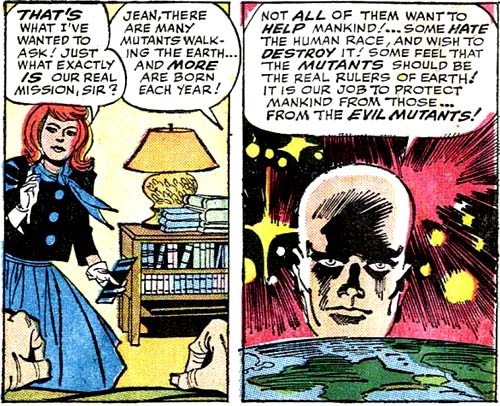

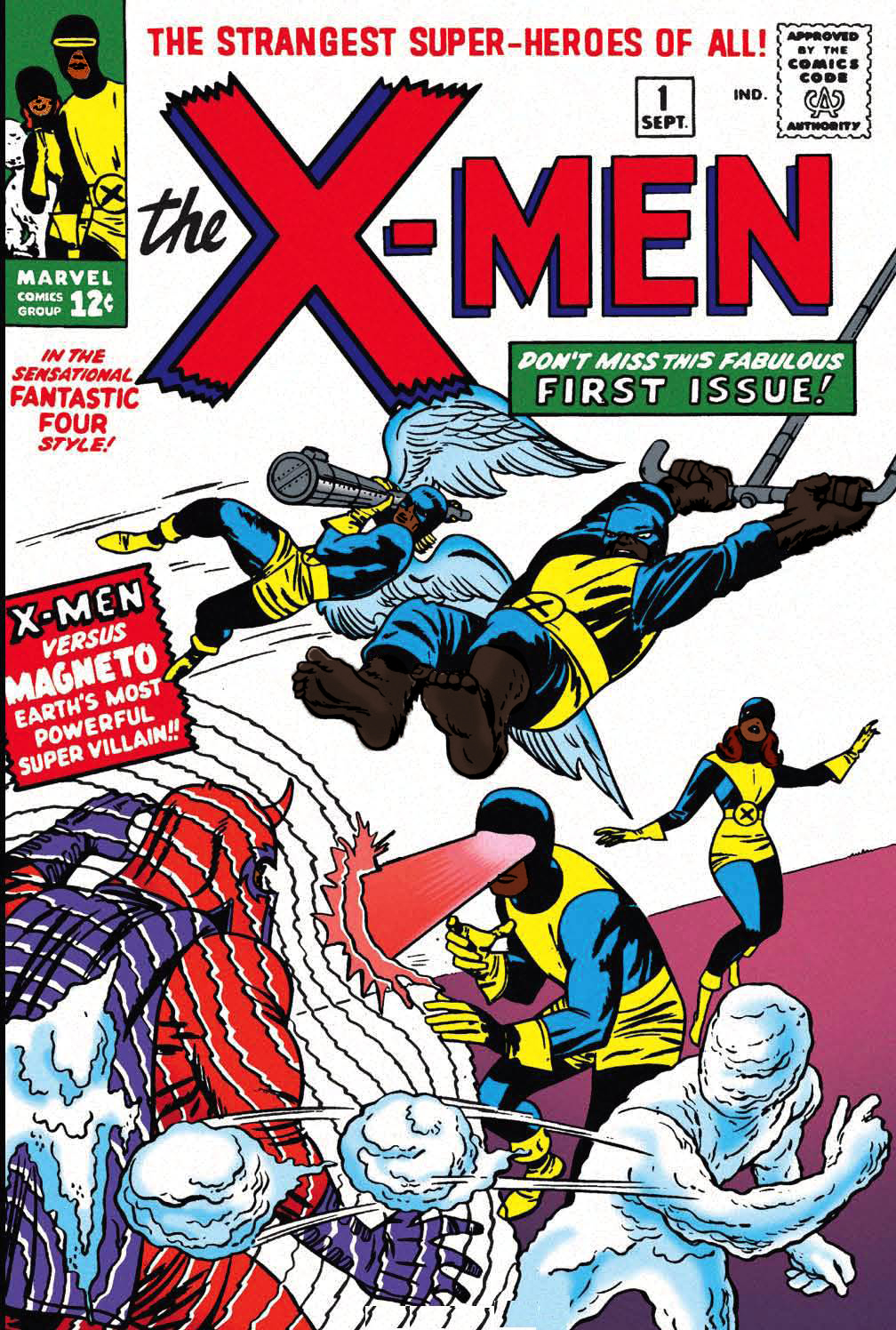

The first issue of X-Men was written by Stan Lee and published in 1963. The fictional world, which continues today in the Disney-owned Marvel Universe, featured super-powered teenagers who worked in a group as the X-Men. Unlike other characters that Stan Lee created, these teenagers do not become superheroes through a freak accident, but were instead born with a genetic mutation known as the x-gene that manifests as superpowers (“mutations”) around the time of puberty. They hide their identity as super powered humans for fear that they will be killed by angry mobs.

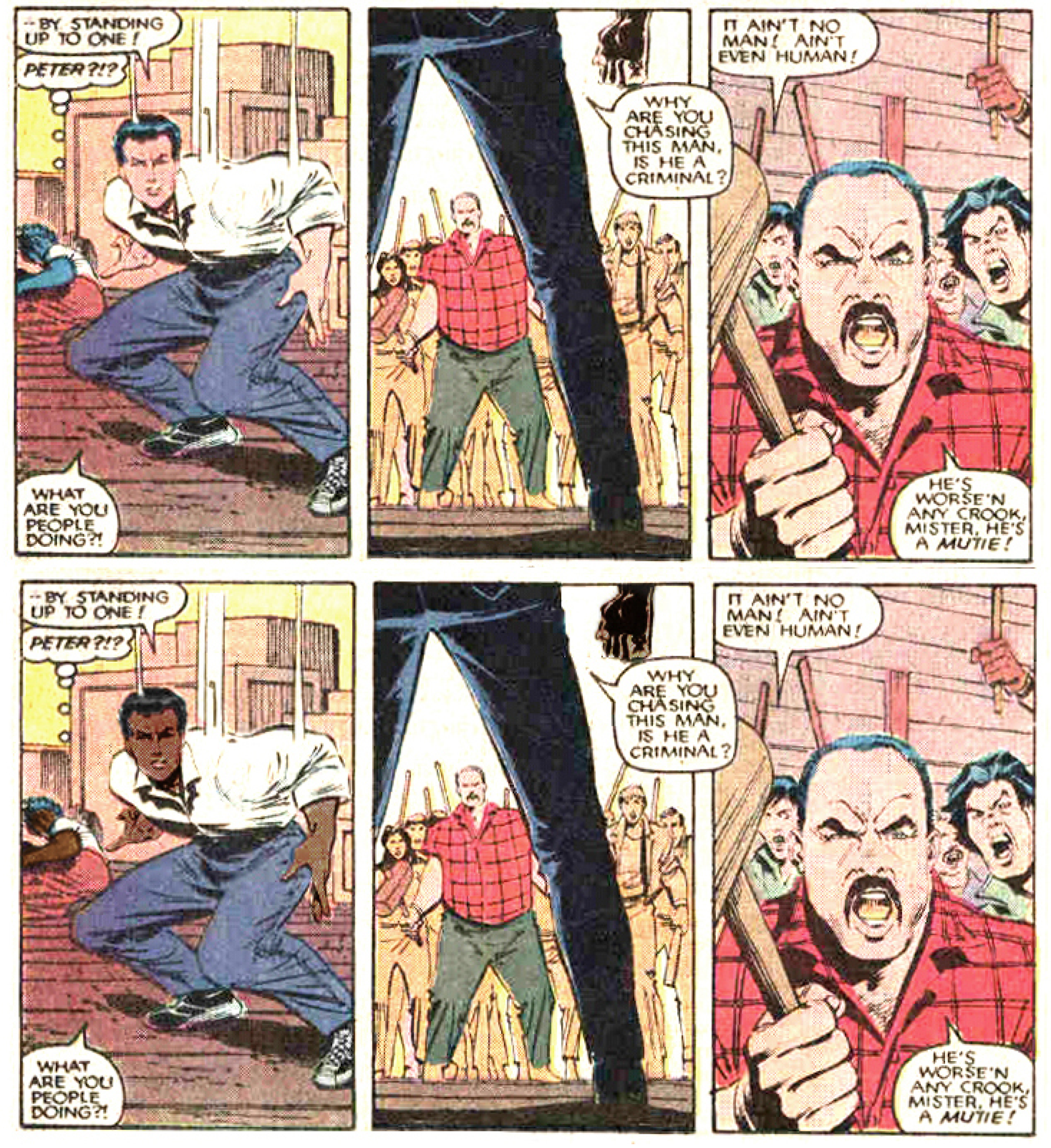

An image of mob violence from the Stan Lee and Steve Ditko era.

Stan Lee has explained that his main impetus for having the superheroes be mutants was that he wouldn’t have to invent origin stories for every new character. However, he also claims that the comparison to Civil Rights was present from the start. In a recent interview he said, “It not only made them different, but it was a good metaphor for what was happening with the civil rights movement in the country at that time.”

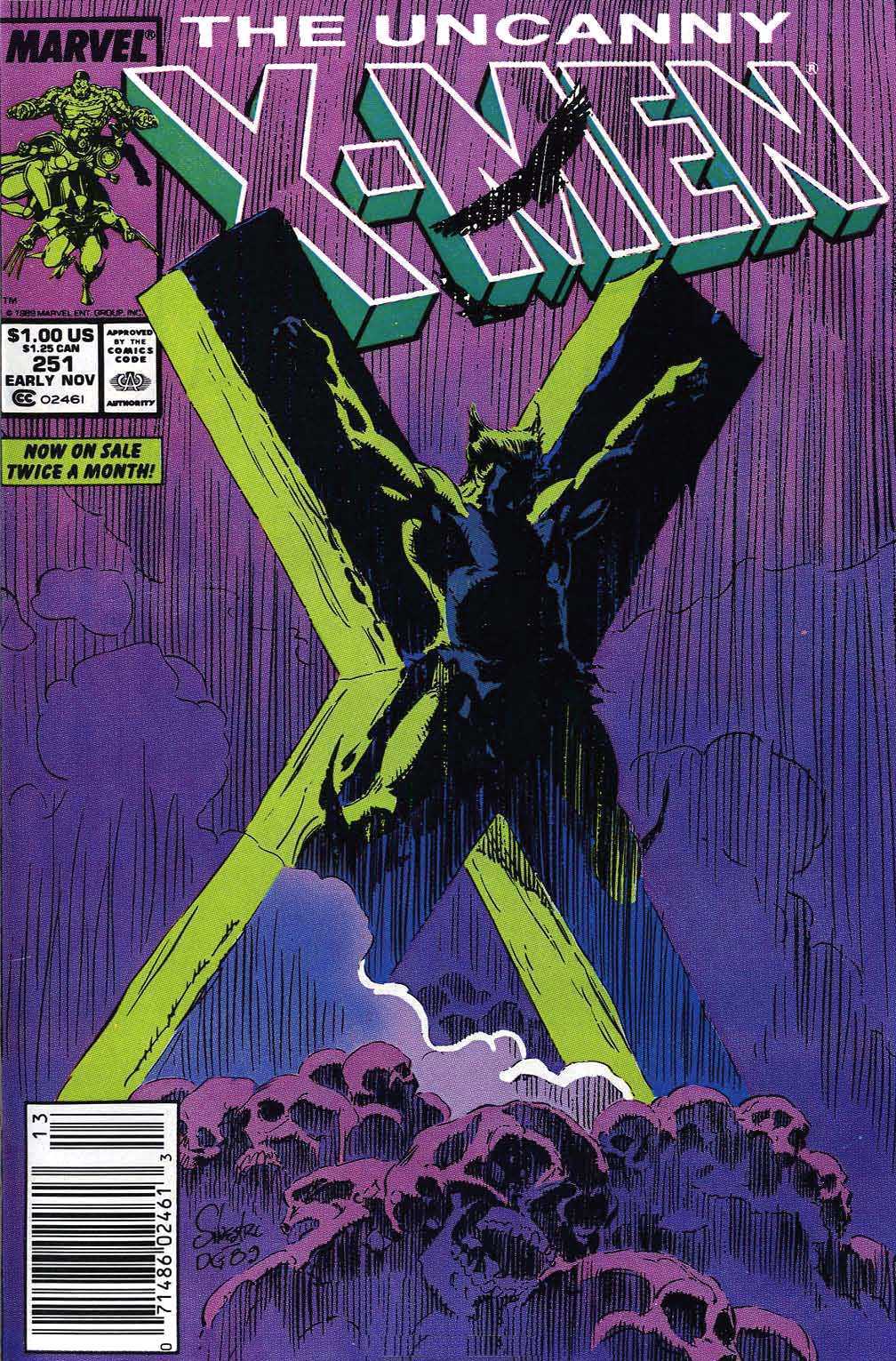

Since the original, largely unpopular episodes written by Stan Lee, dozens of other writers (most of them white men) have built and expanded the world of the X-Men. New characters were added, and the discrimination that mutants like the X-Men face in the Marvel Universe was developed. Over time, the dynamic of the “feared and hated” mutants who nevertheless defend ordinary humans has been used to explore different dynamics of power and privilege*. These include anti-Semitism, racism, and LGBT issues (ableism and sexism, though extremely relevant, are almost never addressed).

Noteworthy X-Men events with social implications include:

—The founding of Genosha, a fictional country where mutants are enslaved – a direct reference to Apartheid.

—A genocide of 16 million mutants.

—The development of a cure for the x-gene mutations, causing a schism in the mutant community.

—The spread of the Legacy Virus, a disease that targeted only mutants. The virus is a clear reference to the AIDS virus and its impact on the LGBT community.

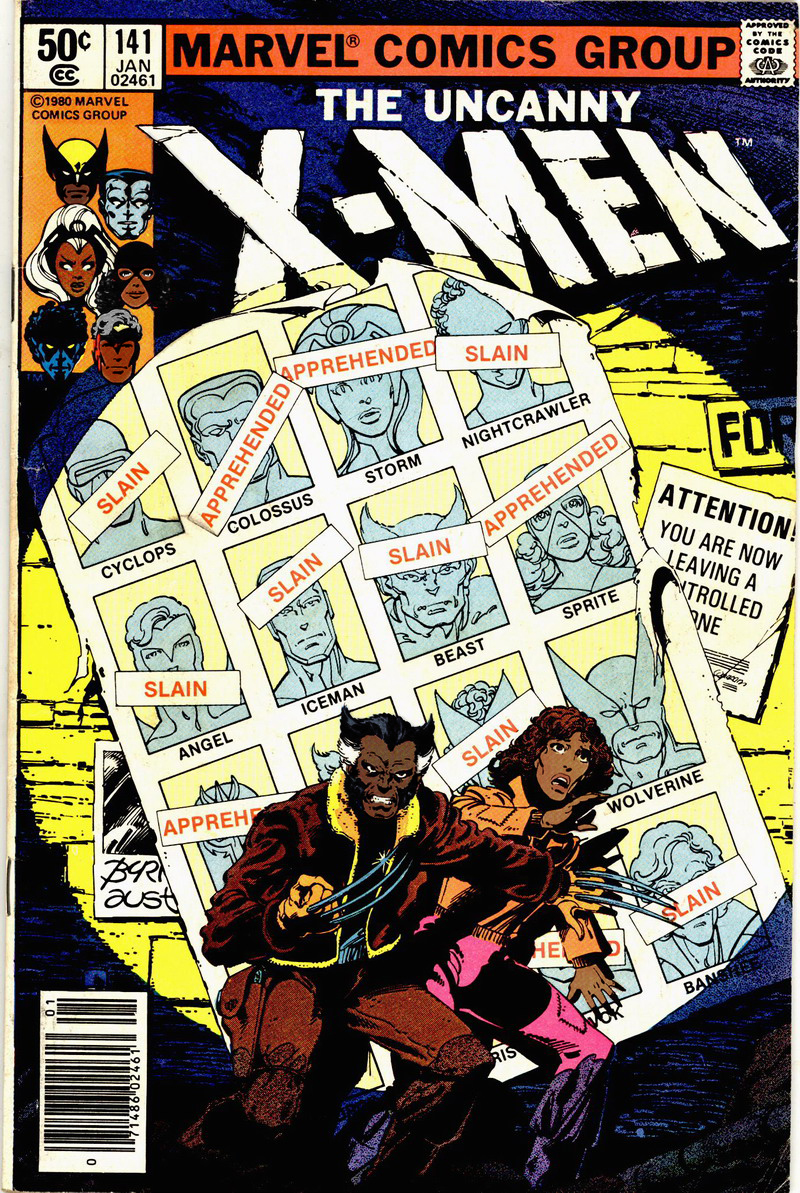

Despite the flexibility of “mutantity” to be a stand in for various aspects of privilege, the Civil Rights movement and racism are topics that come up repeatedly in the X-Men comics and films. Professor X is repeatedly compared to Martin Luther King, and the dream of “peaceful integration.” Magneto, his enemy, advocates for violent mutant revolution and quotes Malcolm X**. Characters in the comic use the fictional slur “mutie” and compare it to racial slurs.

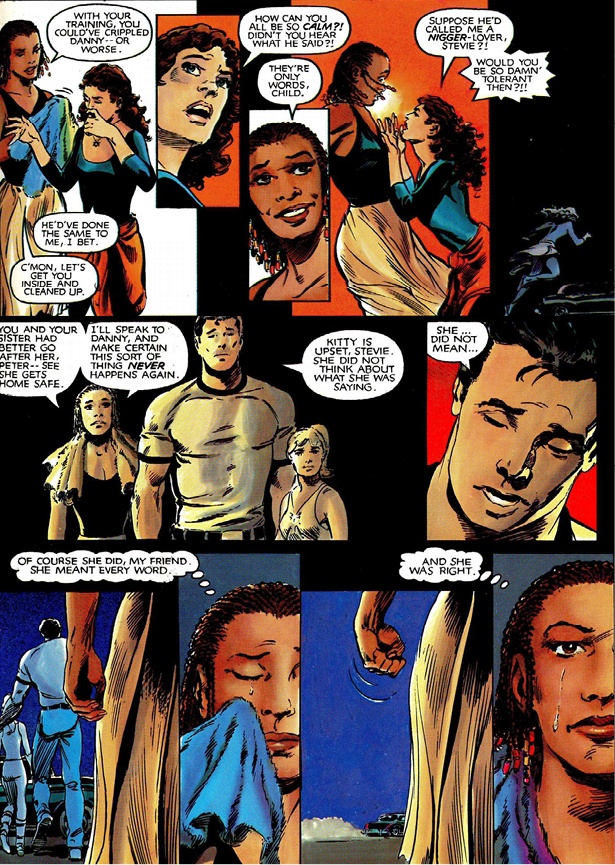

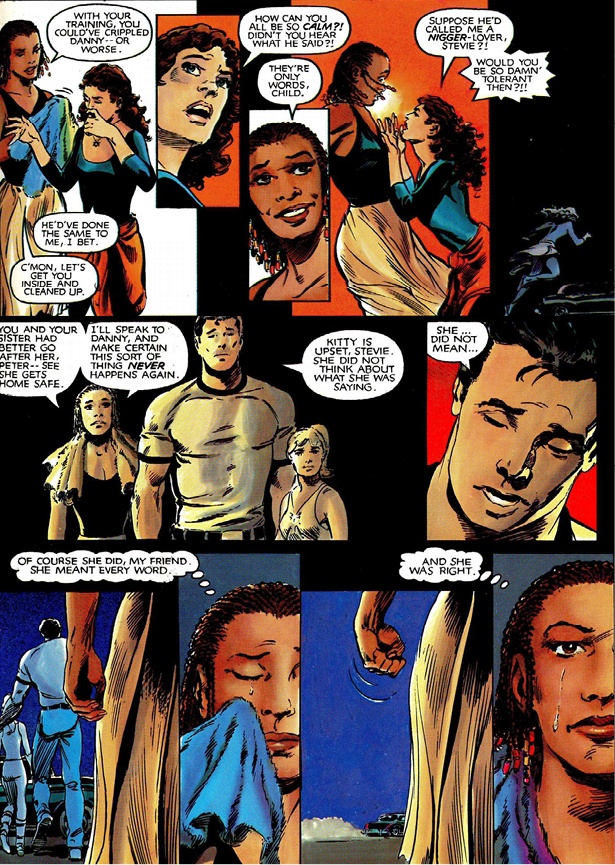

This sequence from God Loves, Man Kills by Chris Claremont shows how Storm and other nonwhite characters are used as props to legitimize the idea that the X-Men are an oppressed minority.

What’s disturbing about the series is that is that all of these issues are played out by a cast of characters dominated by wealthy, straight, cisgender, Christian, able-bodied, white men. The X-Men are the victims of discrimination for their mutant identity, with little or no mention of the huge privileges they enjoy.

Neil Shyminsky argues persuasively that playing out Civil Rights-related struggles with an all white cast allows the white male audience of the comics to appropriate the struggles of marginalized peoples. He concludes that, “While its stated mission is to promote the acceptance of minorities of all kinds, X-Men has not only failed to adequately redress issues of inequality – it actually reinforces inequality.”**

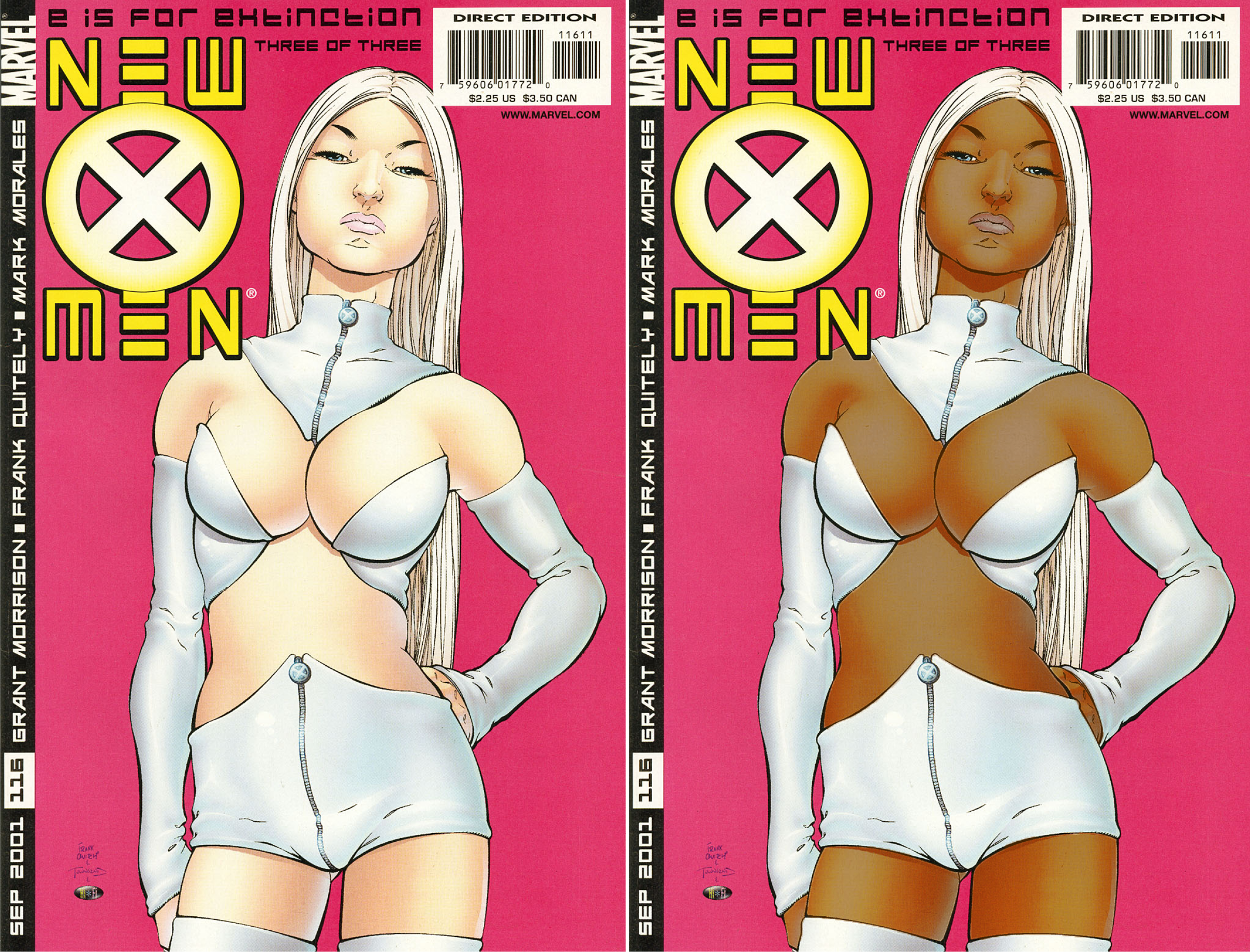

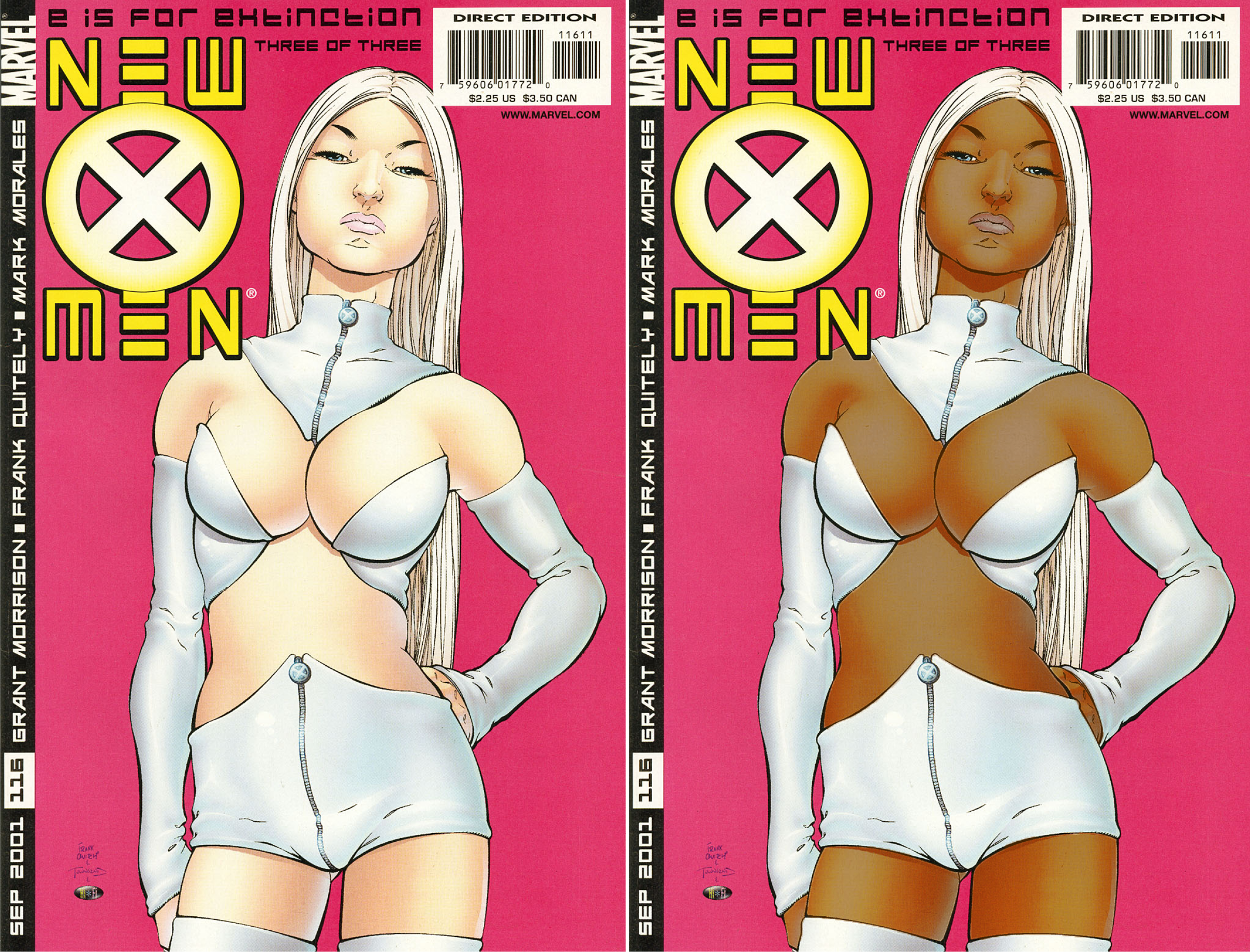

An unedited image from the comics.

I wanted to remix these stories and imagine what they could have been if they had dealt with actual instead of fictional dimensions of privilege. Searching through 50 years of X-Men comics, I selected a half dozen iconic images and scenes relating to discrimination. In these images, I edited the comics so that every mutant had a skin color that was some shade of brown.

In the alternate universe where the all mutants are black, many events in the X-Men history become actual social commentary because they are dealing with real dimensions of power. Reading about black teenagers standing up to a largely white mob is different than reading about white teenagers in the same situation. These images show that when the writers of the X-Men do comment on social issues, the meaning of these comments is hampered and distorted by the translations from reality to fantasy and fantasy back to reality.

<

<

Left, the original frames in which Colossus stands up to a mob. Right, the edited version of the same sequence from the project X-Men of Color.

Re-coloring the X-Men so that all mutants are people of color not only makes the themes of discrimination more relevant, it also introduces hundreds of non-white characters who are complex and fully realized. This is something that’s lacking from the current Marvel Universe. Why is Psylocke not only an Asian person of British descent, but also a ninja? Why is Storm not simply a mutant of color, but an African witch-priestess? As comics great Dwayne McDuffie said, “You only had two types of characters available for children. You had the stupid angry brute and the he’s-smart-but-he’s-black characters.” There’s certainly more roles for a non-white characters now than when he said that in 1993, but most super hero comics are written about characters that were invented decades ago. By recoloring the comics, we can grandfather characters into the Marvel Universe who are not defined by their race.

Before and after comparison of Emma Frost.

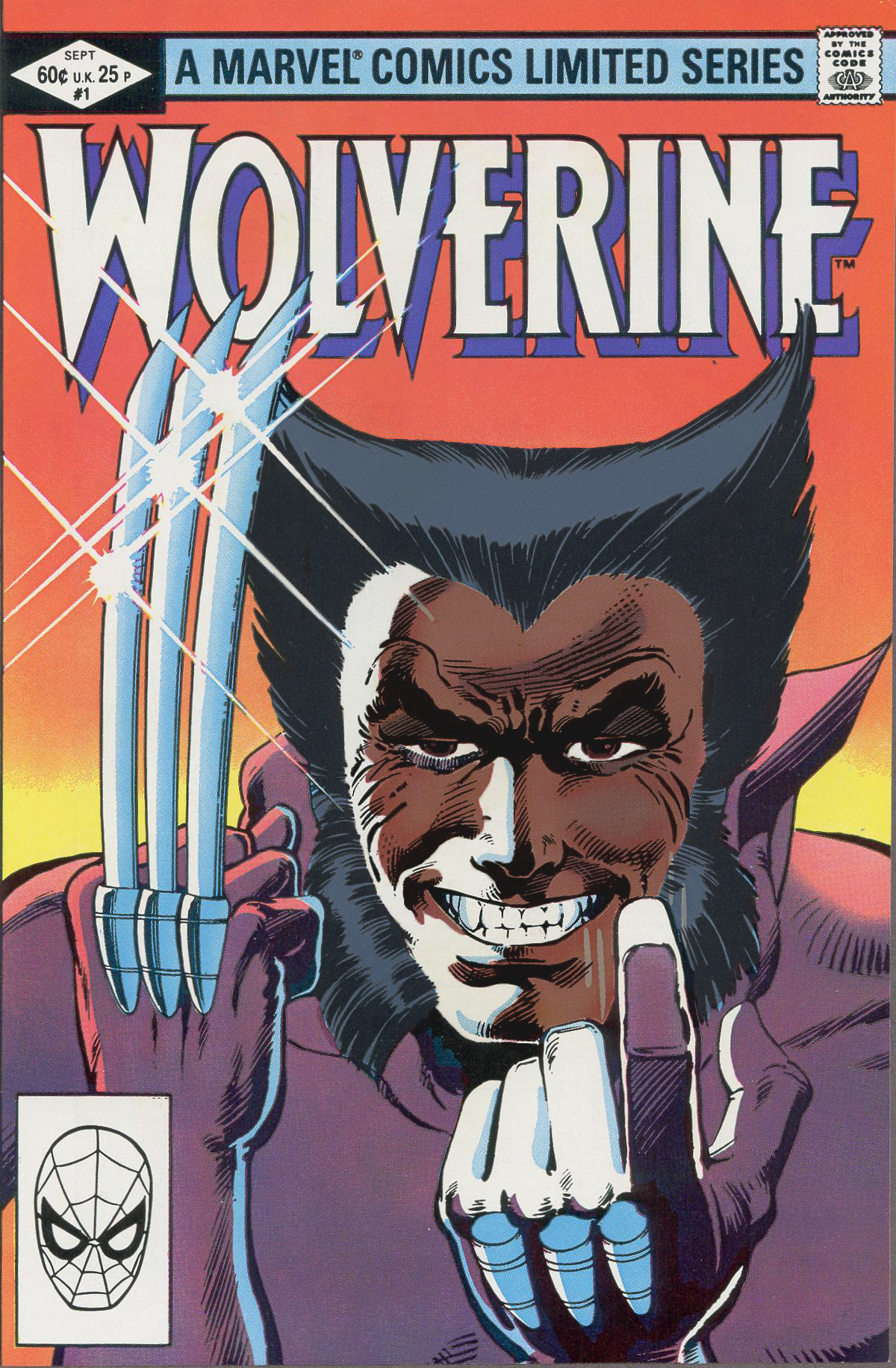

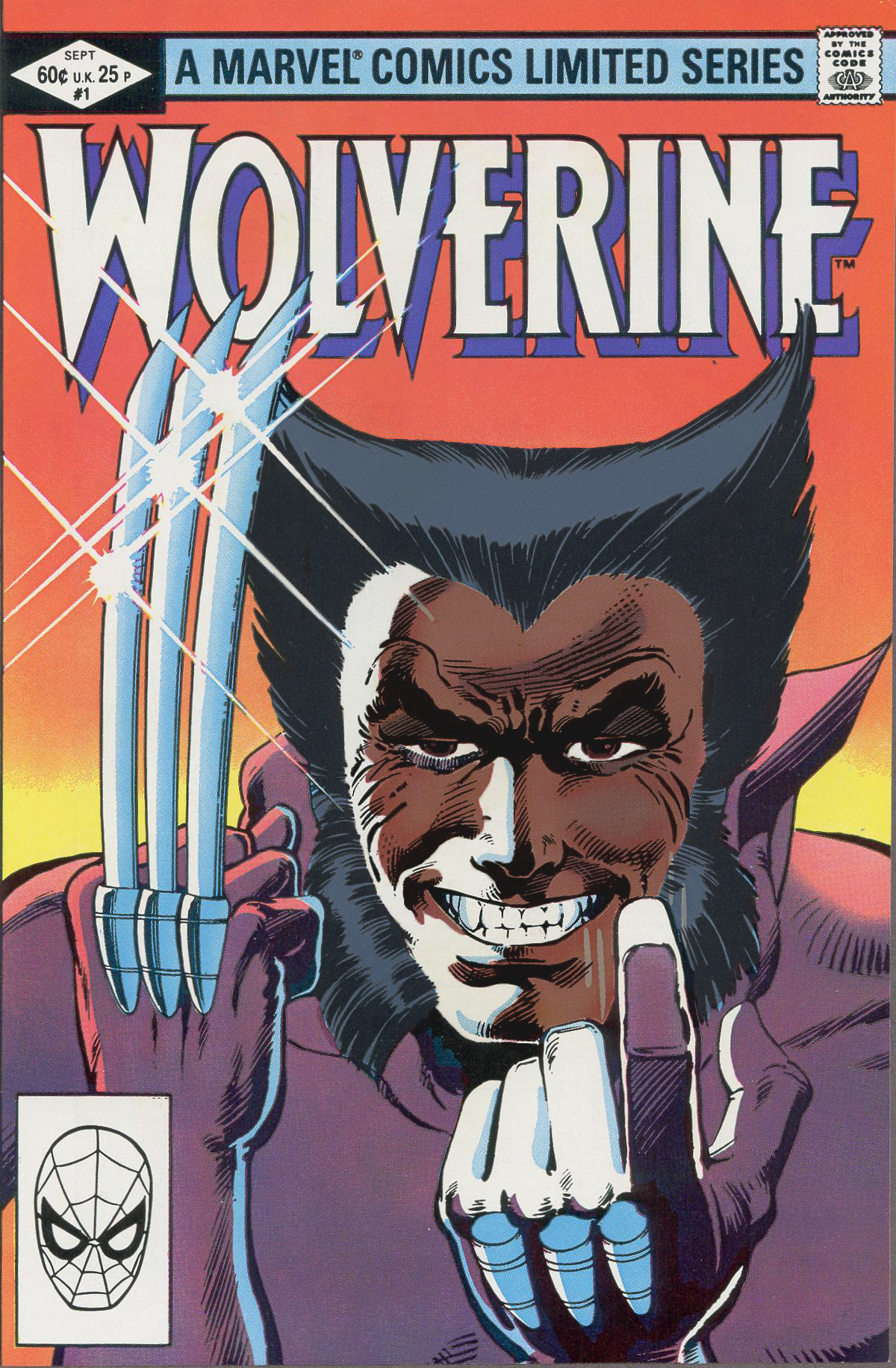

Simply changing the skin color of the mutants obviously doesn’t address all of the issues around privilege in the Marvel Universe. The visual and narrative sexism that permeates superhero comics remains intact. Some characteristics of white characters also become negative stereotypes when applied to non-white characters. Wolverine is a symbol of wild, untamed, white male power, but when I recolor his skin to imagine him as a person of color, his snarling, predatory aggression reads as a stereotype of wild black men. This is a great demonstration of the way that white male characters are free to inhabit any role, whereas centuries of accumulated stereotypes shape the way we understand people of color in fiction***.

An edited image from the series X-Men of Color.

Promoters of the X-Men have spent years trying to convince audiences that these white characters are tapping into the struggle of black Americans. Strange as the substitution of white men for black activists may seem, it’s not unique. Fantasy universes often comment on social issues through the veil of imaginary prejudices****. My goal is that by looking at these images people will question whether an invented minority is really the best way to understand our country’s history and practice of race-based violence.

You can find a few more images at my website.)

Other resources related to this issue:

More NonSense: No More Mutants by Michael Buntag http://nonsensicalwords.blogspot.com/2010/10/more-nonsense-no-more-mutants.html

We Have The Power To Change MARVEL and DC Comics: Support Diversity, Support Miles! by Jay Deitcher http://www.unleashthefanboy.com/editorial/we-have-the-power-to-change-marvel-and-dc-comics-support-diversity-support-miles/44986

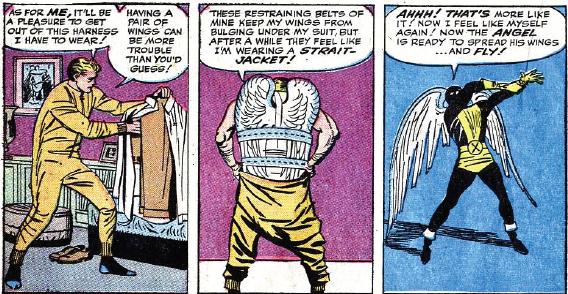

* The most appropriate metaphor for the original Stan Lee comics is probably invisible dimensions of power such as LGBT issues or religion. In the original comics, the X-Men hide their mutations in order to pass as humans (Angel uses belts to strap his wings down under a suit coat). In later generations, some of the mutants are visibly mutated to the point they could never pass as humans.

** Shyminsky also notes that recent generations of X-Men writers have reacted to the politics of appropriation in the series’ history. He cites Grant Morrison’s U-Men as an example.

***I think it’s interesting that the same characteristics that make Wolverine a white male icon are also regressive stereotypes of black men.

****I often think of house-elf slavery in Harry Potter, but it actually starts much earlier: