“But before I be a servant in White heaven, I will rule in a Black hell.” Killer Mike, “God in the Building”, I Pledge Allegiance to the Grind, Vol. II

Promotional poster for Belle, directed by Amma Asante

Early in Amma Asante’s socially conscious romance Belle (2013), audiences spy a British nobleman walk with purpose through a lower class section of an unnamed port city. Humid, overpopulated streets obstruct the uniformed Royal Navy Captain’s passage. The nobleman enters an attic dimly lit by a small window and sparse candles where a middle aged Black woman waits for him. Dressed in everyday homespun and a worn apron she stands alongside a quiet tan child with brilliant brown eyes. Prepared and dressed by the matronly woman, the silent girl holds a simple doll and stands impassive, unmoving, and observant; her simple hairpin struggles to contain an infinite cascade of light sienna locks. After the untimely death of her mother, the nobleman plans to whisk the little brown girl away to his family, to her birthright. To privilege. The nobleman kneels, and offers chocolate. Reluctantly, the girl accepts. The year is 1769.

“How lovely she is,” the nobleman exclaims softly. “Similar to her mother.”

It’s easy to regard the nobleman’s plan as obvious and uncontroversial given today’s standards. Leaving for the British West Indies on a navigational expedition, the Captain intends to leave the child in the care of his uncle, William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, and Lord Chief Justice of the British Empire. With family. However, late Eighteenth Century Great Britain revolves around its slave economy; colonial procurements replete with agricultural wealth, exotic goods and slave labor revolutionized British high society. Propriety, refinement, culture — these were the watchwords of an Enlightenment where civilized humans were encouraged to exert the “freedom to make public use of one’s reason in all matters”, according to Immanuel Kant [i]. Kant and his enlightened contemporaries judged persons of African descent incapable of higher order reasoning; animalistic Blacks offer stark counterpoint to virtuous White humanity. British nobles viewed Africans as subhuman beasts, unfit for culture, education, or reason. As slaves, Africans lacked any capacity for aesthetic sensibility, according to Enlightenment thinking. Slaves were property, and property does not think, feel, or reason. Given this, the nobleman’s request runs afoul of his homeland’s strict social order; a global empire that demanded unfree labor for economic stability could not conceptualize Black humanity. One locates diasporic Blackness during this period on balance sheets, cargo manifests, and maritime rapists’ salacious reports, not within British mansions’ gilded contours.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant (1782),

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Lord and Lady Mansfield reservedly accept the little brown girl, Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay, into Kenwood House, a massive estate in Hampshire Village, London. Left alone soon after her arrival, Dido walks among Kenwood House’s massive portraits, and through her wary brown eyes viewers spy a visual synthesis of Enlightenment individualism and slavery apology. Painted by preeminent portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds, a founder and inaugural president of the Royal Academy, exhibited at the Academy in 1783 as Portrait of a Nobleman,[ii] and housed today within the Paul Mellon Collection at the Yale Center for British Art, Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant (1782) welcomes all to eighteenth century British machismo.

Stanhope, encased in unblemished armor, stands upon an active and sweltering Caribbean battlefield, sword in hand, both preternaturally calm and oddly petrified. An adoring brown youth holds Stanhope’s plumed helmet and gazes above, awestruck at his master’s magnificence. Reynolds paints Stanhope as desperate to impress all with martial skill earned in the slick red mud of the courageous and the damned but enhanced in an elite art studio; this oil-on-canvas press release asserts virility to contemporaries and whispers vulnerability to posterities. Stanhope, barely a man, plays at war. [iii] Below foreboding clouds Stanhope’s pale, effete visage peers above glistening golden armor; his pointed, boyish chin, hairless face, and perfect, Proactiv complexion force modern viewers to regard English nobility as special, refined, comfortable, free from want or struggle. Contrast this against the adolescent Servant shoved against Stanhope’s left, against guileless brown smiles trained by the lash, against another Marrakech rich in human capital but poor in civic defense, and Stanhope’s serenity approaches incredulity. Under Reynolds’ direction Stanhope does not stand with us, but above us; there’s no sweat upon his ghostly brow, no dirt under his manicured fingernails, no blood on his thin steel blade.

Bartholomew Dandridge, A Young Girl with a Dog and a Page. (1725)

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

One can easily imagine Reynolds’ conversation with Stanhope upon completion of this commissioned work; the abject flattery, the direct reassurances, the stroked ego, the payment for service rendered. With this portrait Reynolds both thunders Anglo-Saxon dominance and whispers sly rejection of that fantasy, a noble veteran revealed as farce without his helmet. Modern criticism of this object centers on the anonymous Black Servant whose illiberal assistance literally frames Stanhope’s polish. Similarly, in Belle, Dido’s inarticulate frustrations with her uncle’s desire for a commissioned portrait of herself and her cousin Elizabeth Murray is centered on her silent disapproval of the dark servant shadows who frame British portraits during this era, contrasting White civility with Black servitude. Paintings like Bartholomew Dandridge’s A Young Girl with a Dog and a Page (1725) and Arthur Devis’ John Orde, His Wife Anne, and His Eldest Son William (between 1754-1756) typify Enlightenment prejudice against Black personhood; baby-faced background slaves assist blanched central figures who thoroughly enrapture the pitiful anonymous with sophisticated British grandeur.

With dark, curly hair and infantile wonder, the Servant in Sir Joshua Reynolds’ Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant anticipates every cute Black child ever seen in Western popular culture, from Keisha Knight Pulliam and Raven-Symoné on The Cosby Show to Noah Gray-Cabey on Heroes and Marsai Martin on Black-ish. Cherubic and brown, servile and friendly, these children of the darker nation deflect others’ revulsion toward their melanin with youthful gaiety and infectious innocence, and Reynolds co-opts this to both parallel the untested manhood on display and show Stanhope’s privileged freedom as natural and moral.

The peculiar institution’s American apologists often invoked the artless Sambo stereotype to justify their generational plunder of Black labor, wealth, and self-determination; it is easier to justify the transatlantic slave trade’s depraved criminality when we consider those reduced to beasts of burden emotionally underdeveloped and cognitively deficient.

“Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous. But never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never see even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture. … I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” — Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, Query XIV (1784)

Arthur Devis, John Orde, His Wife Anne, and His Eldest Son William. (between 1754 and 1756)

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Art historians speculate wildly about the Servant’s life, and the lives he represents. Whether colonial acquisition or indentured employee, the Servant signifies Great Britain’s longtime human trafficking and exploitation; modern viewers experience Stanhope as majestic, proud, and free, largely because history’s judgments identify the barbarous subjugation and domestic terrorism behind the Servant’s awestruck gaze. Mouth agape, eyes wide, the angelic brown face registers wonder at a life without whips and chains and commands and fear; a life lived free. Liberated. The Servant illustrates lifelong submission to chattel slavery; Reynolds’ otherwise unmoving portrait appropriates the systemic plunder of Black bodies and the bureaucratic corruption of Black labor to establish and augment Western global hegemony. White dominance. Notice the intricate detail attended this secondary, unnamed, background figure. Regard the Servant’s cowering awkwardness and unsure social position, both justified by the coerced assistance he renders. Compositionally, the patient attendant holds the viewer’s gaze and conscripts recognition of the static central figure. The Servant’s immaterial, indiscernible, questionable humanity fascinates, today more than yesteryear; because the Servant is inferior, Stanhope is superior. Because Blackness cannot equal freedom, Whiteness approximates divinity.

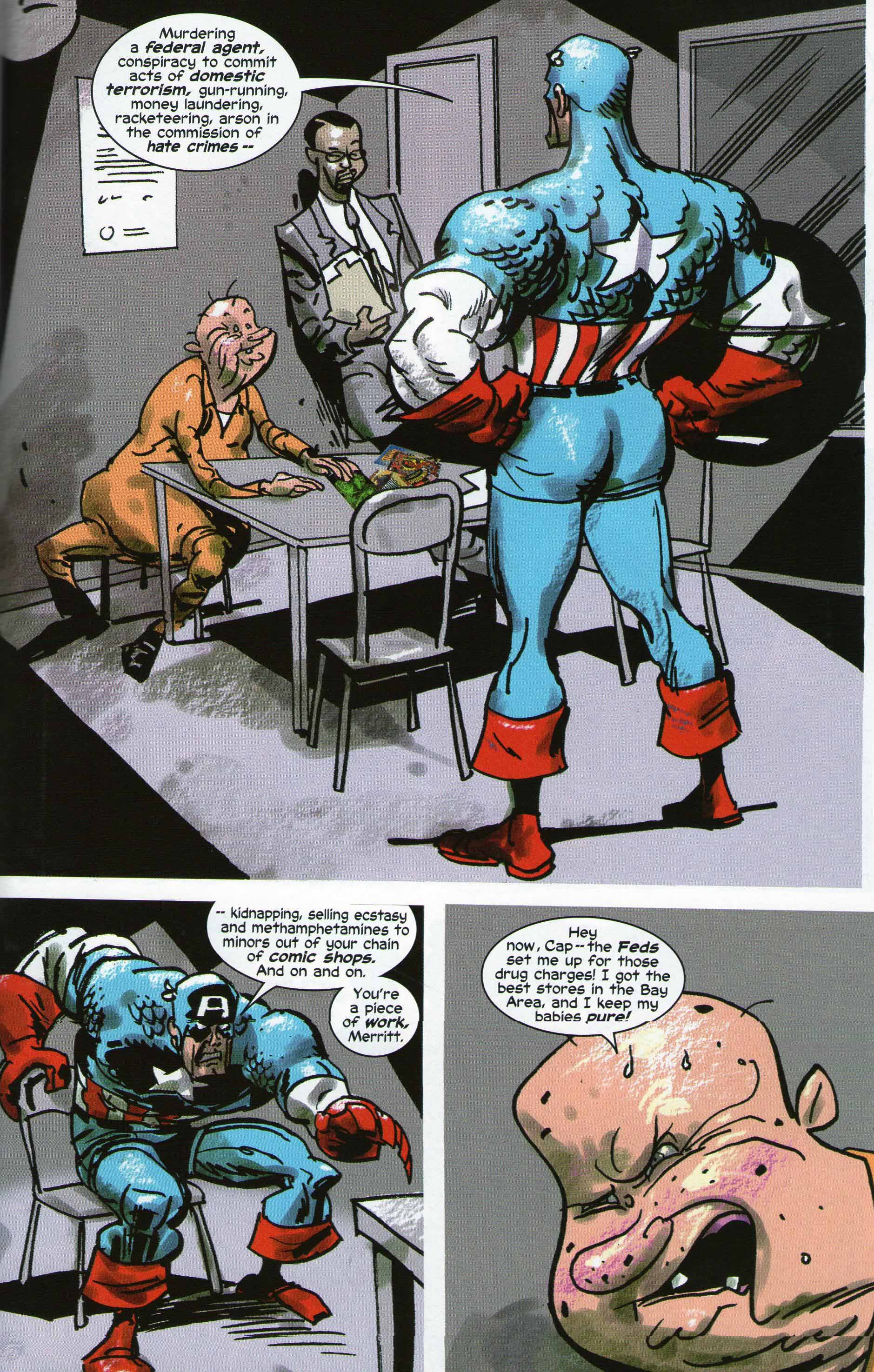

Sam Wilson and Steve Rogers. Man and Superman.

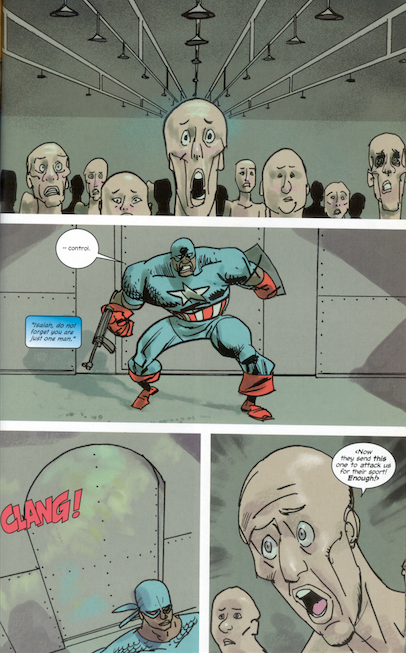

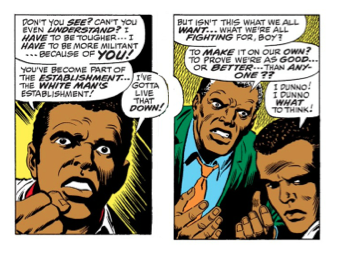

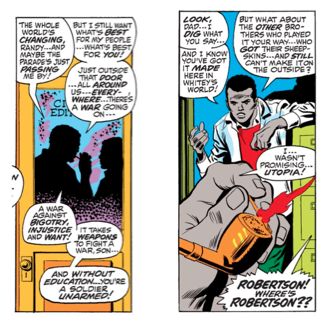

The intended narrative of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant operates as an eighteenth century White male power fantasy. Modern superhero comic media fans easily recognize this dynamic; mainstream superhero comic companies publish cartoonish variations on this worn, well-traveled groove ad nauseam to meet monthly operating expenses. Whether as friendly bystanders, costumed sidekicks, everyday henchmen or caped vigilantes, race and gender minorities exist in superhero comic media to validate and define the normative Whiteness central to the genre’s narratives.

Take Captain America: The Winter Soldier: early in the film we watch an athletic Black man sprint effortlessly around the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Wearing exercise shorts and a shapeless grey sweatshirt on a crisp spring day, viewers indulge athleticism, defined. Landscape shots capture republican majesty at the Washington Memorial and the U.S. Capitol. Suddenly a blurry blonde humanoid whizzes past, and frenetic limbs pump faster than the naked eye can detect. Comical frustration darkens Grey Sweatshirt’s expression: once, twice, thrice, the splendid blond beast laps the public track while Grey Sweatshirt bellows disbelief at his strained cardiovascular system’s futile effort. Played for laughs, this scene introduces viewers to Sam Wilson, the cheerful brother with an easy smile and Marvin Gaye on standby who extends friendship to a man living outside his era and outside his war, and who reminds viewers of the extra-normal abilities experimental industrial steroid injections granted this Greatest Generation throwback. “Blessed are the meek; for they shall inherit the Earth,” Jesus Christ teaches in Matthew 5:5; Marvel Studios’ Captain America: The First Avenger imagined that inheritance as tactical perfection augmented with avant-garde biochemistry and electroshock therapy. Doubtless, the screenwriters and producers of Captain America: The Winter Soldier applaud their intentional rejection of Black male stereotype, but to watch Steve Rogers literally run circles around Sam Wilson establishes a questionable on-screen dynamic that complicates this superheroic bromance at conception. In Captain America: The Winter Soldier, viewers experience the White protagonist’s superior physicality in contrast to a Black inferior, Charles Stanhope on creatine painted by Industrial Light and Magic. All this, to deify military service.

Captain America and the Falcon. Photo Credit: Zade Rosenthal ©Marvel 2014

Superhero comics employ violence to establish justice. To ensure domestic tranquility in Gotham or Hell’s Kitchen or Space Sector 2814 jackbooted vigilantes adorned in colorful, form-fitting leather and Kevlar ground and pound the criminally confused outside all legal authority. The superhero concept appeals to the adolescent desire to compel order through brute force, to define peace as the absence of credible threats. No matter how intellectually gifted or technologically adept or physically remarkable or preternaturally perceptive or unabashedly godlike, superheroes use violence to solve problems, foreign and domestic. The depictions of Charles Stanhope and Steve Rogers mentioned above show unsophisticated, immature White males who wrest manhood from their military experience, who telegraph masculinity by glorifying war. Yesterday’s crude colonial plantations and human trafficking syndicates drained profit from a world order enforced by eighteenth century British naval expenditures; today’s multinational technology conglomerates and global financial institutions wring fortunes from American guaranteed global stability. In this unipolar world, where the American hegemon assumes responsibility for political and economic stability from Minneapolis to Medina, from Seattle to Shenzhen, from Albuquerque to Addis Ababa, superhero action figures like Captain America argue the Athenian position in the Melian Dialogue; Rogers’ very existence symbolizes undisputed American technological supremacy. Of course, Rogers is not Cable, or Magog, or the Punisher, all logical extensions of the super-soldier concept updated for modern, antiheroic eras where callous scribes and tragedy pornographers painted scarlet horror in rectangular comic art panels while illiterate dealers and nihilistic gangsters sprayed arterial abyss on letterboxed nightly news broadcasts. Frozen in the cheery bombast of the last just war, Rogers’ outdated moral binary and Franklin Roosevelt phonetics convince comic fans that the extra-normal abilities he exploits service peace; given this conceit, we watch Rogers conscript Sam Wilson and Natasha Romanov into an ad-hoc terrorist conspiracy in Captain America: The Winter Soldier to incapacitate and scrap three floating, flying aircraft carriers authorized by American policymakers, funded by American taxpayers, staffed by untold hundreds, worth untold billions, because he alone determines the strategic advantage of perpetually aloft gunboat diplomacy counterproductive, an existential threat to world peace. The floating nuclear version at sea today does not enter the debate.

)Su•per•he•ro (soo’per hîr’o) n., pl. – roes. n., pl. – roes. A heroic character with a selfless, pro-social mission; with superpowers, extraordinary abilities, advanced technology, or highly developed physical, mental, or mystical skills; who has a superhero identity embodied in a codename and iconic costume, which typically express his biography, character, powers, or origin (transformation from ordinary person to superhero); and who is generically distinct, i.e. can be distinguished from characters of related genres (fantasy, science fiction, detective, etc.) by a preponderance of generic conventions. Often superheroes have dual identities, the ordinary one of which is usually a closely guarded secret. superheroic, adj. Also super hero, super-hero. — Peter Coogan, Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, ©2006, pg. 30

Cyclops & Wolverine dismantle Sentinels. Comic unknown.

The superhero is a deceptively simple concept. The reactionary militarism, the thoughtless violence, the binary morality, the unquestioned righteousness, the colonial sociology — all of the superhero genre’s boyish charm reinforces the Western imperialist impulse to control, to order, to rule. The superhero genre does not promote fantastic Western imperialism alone: science fiction, espionage fiction, and medieval fantasy win popular culture’s hearts and minds with similar power fantasies designed for adolescent White straight males, sold globally. Still, every Wednesday, carrot-topped Caucasian perfection dons skintight primary colored lycra to unleash energetic ruby strobes at giant purple killing machines crafted in man’s image while a hairy Crossfit junkie with indestructible metal claws hacks and slashes fundamentalist cannon fodder amid blasé exurban spectators numb to repetitive superhuman brawls but unnerved all the same. Every Wednesday, superheroes seduce the innocent with disturbing commentaries on justifiable public conflict, acceptable casualty rates, and unspoken racial hierarchies. Superheroes are White male power fantasy distilled to narcotic purity, blue magic on white cardboard wrapped in clear polypropylene to show variant cover art. Consider Jim Lee as Frank Lucas.

Peter Coogan, founder and director of the Institute for Comics Studies, defines the superhero through a narrative triumvirate: selfless mission, amazing ability, and secret identity, all symbolized by a special moniker and distinct costume that elevates the new extra-normal persona to cultural iconography. The Batman’s elementary school ambition to channel elemental fear and unspeakable tragedy into a personal war on crime impacts everything about the character, from his costume’s shadowy color swatches, morose blue-grey later rendered midnight black, to his scalloped cape’s predatory motion silhouette, to his variable but always recognized centrally placed Bat-logo. Like Michael Jordan, we recognize Batman in profile with nothing more than dark cranial contours as evidence. Everything Bat-related identifies with a central simplicity: punish the bad man who killed Mommy and Daddy. †Law and order, uncomplicated.

“Despite what you may have heard, Superman is not a complicated character. He’s an extremely simple idea: A man with the power to do anything who always does the right thing. That’s it.” — Chris Sims, “Ask Chris #171: The Superman (Well, Supermen) of Marvel”, ComicsAlliance.com

This is the problem. For nearly eighty years, superhero comics etched the world in bright Crayolas, without emotional nuance or political complexity, to display imagined realms where the mundane and the fantastic coexist without incident. When the soapy X-Men adventure in the Savage Land’s meteorological impossibility, when the stately Justice League intercept planetary conquerors unfazed by Earth’s gravity or thermonuclear weapons, everyone drawn and colored and inked and lettered in panel conducts themselves in accordance or in conflict with mainstream, middle-class White American social ethics. The ‘right thing’ Chris Sims believes Superman insists upon remains a moral good defined in panel by rural Midwestern Protestants, and the superhero concept’s resultant normative Whiteness enjoys broad, international appeal. Most superhero comic fans regardless of race or creed or national origin judge Superman and his compatriots as truth and justice’s universal avatars, Golden Rule morality made myth. Because of this fantasy, fanboys and fangirls of color imagine themselves as living Kryptonian solar batteries who ignite still, unmoving skies with chaotic blue flame as they race through lower Earth atmosphere trailing angry pyrotechnics and leaking ozone while millions watch breathlessly, transfixed at an ungodly spectacle where petrified cosmonauts expect certain death after heat shield failure during reentry only to meet a scarlet and navy blue blur branded with hope’s own chevron in the upper stratosphere. The darker nation also wants to play the hero; they too, wish to be redeemed.

Make no mistake: this is a redemption song. The desire for full inclusion in superhero comics both behind the cowl and before the camera by patient progressive integrationists yearns to humanize those dismissed as unfit for heroism by superhero comics’ irrepressible identity indifference. Race, gender, sexual orientation: hashtag activists and comic bloggers clamor for more representation of all these political identities in superhero comics, television, and movies; whether straight-to-Blu-Ray animation or tentpole summer blockbuster, non-traditional superhero comic fans cajole, threaten, and shame mainstream superhero content creators into diversifying superhero and villain properties. Everything’s appropriate — racebending established heroes when franchises jump from print to live-action, with unconventional character origins that discard existing character history, cross-racially casting superhero protagonist roles, even cowl-rental, the shift of established major superhero properties from White male classics to new-age minority sidekicks — so long as nerds of color and their progeny revel in superheroes who approximate their phenotypes. I charge that this desire for inclusion — this need to see oneself in the corporate culture one consumes — is not ethical. When applied to the superhero concept, this inclusion is not possible.

Anti-busing rally at Thomas Park, South Boston, 1975 Copyright © Spencer Grant

Coogan’s definition is incomplete. To craft a superhero, add Whiteness to the mission-powers-identity troika; coat liquid latex and electrostrictive polymers onto the White body, code the costume design with identifiable brand marketing, apply catchy appellation. Done. Artistic license and open casting calls nurture false hope among nerds of color desperate for private sector social approval; these patient progressive integrationists forget that characters who wear their faces but forget their cultures do not promote their interests. These nerds of color also neglect history. Professor Derrick Bell, civil rights lawyer and intellectual progenitor of critical race theory in legal scholarship, wrote in the landmark “Serving Two Masters: Integration Ideals and Client Interests in School Desegregation Litigation” (Yale Law Journal, 1976) on the widening interest divergence between Black parents who sought high quality educational opportunities for their children, and the civil rights attorneys who fought to dismantle state-sponsored Jim Crow segregation with legal remedies applied to public education. For the lawyers, the grand revolutionary movement to desegregate American classrooms secured with Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, KS (No. 1.) the right to ensure “equal educational opportunity” in government funded public schools. Equal educational opportunity meant integrated schools, because for the lawyers only racial integration could guarantee Black children and White children received identical instruction. A generation after Brown, when public school districts needed forced busing to achieve numerical racial parity and angry middle and lower income White parents took to the streets to protest social experiments that designated their children test subjects, national civil rights attorneys from the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund held firm to the conviction that integration alone prophesied American race relation nirvana. This ignored, in Bell’s view, mounting social science evidence that chronicled forced busing-imposed student difficulties, class discrepancies in American integration experiences, and the ethical quandaries presented when civil rights attorneys routinely disregard or rebuff client perspectives.

An ahistorical pretense argues that integration presents the only salvation for an American experiment plagued in infancy by torture, rape, and genocide; chattel slavery and rampant land theft are not ‘birth-defects’, to paraphrase Condoleezza Rice, but cornerstones. From bondage on, Black political thought’s enduring fault line debates separation versus integration; from the titanic Frederick Douglass (“This Fourth of July is yours, not mine.”) through Booker T. Washington’s glad-handing industriousness and W.E.B. Du Bois’ pan-African intellectualism, through Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Birmingham fury at White liberalism and Malcolm X’s snide disdain for White patriotism, through the uneasy synthesis of partisanship and revolution from post-Civil Rights Movement Black elected officials and the criminalized irrelevance of Black Nationalist counterculturalists, the darker nation continually questions American citizenship’s lofty promises and David Simon realities. Casting integration as the sole pathway to postracial Eden in public education, superhero comics, or any other grand American tradition substitutes race visibility for race uplift, and confuses simple appearance with documented progress.

“To sum up this: theoretically, the Negro needs neither segregated schools nor mixed schools. What he needs is Education. What he must remember is that there is no magic, either in mixed schools or in segregated schools. A mixed school with poor and unsympathetic teachers, with hostile public opinion, and no teaching of truth concerning black folk, is bad. A segregated school with ignorant placeholders, inadequate equipment, poor salaries, and wretched housing, is equally bad.” — W.E.B. Du Bois, “Does the Negro Need Separate Schools?” The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 4, No. 3, The Courts and the Negro Separate School. (July 1935), pp. 328-335

Fevered battles over forced busing ripped bare Northern antagonism toward civil rights advocacy; center-left White parents who nominally tolerated nonviolent civil rights activism responded to federal desegregation orders with the same massive resistance found below the Mason-Dixon. Casting the neighborhood elementary school as a ëWhite space‘ where John Q. Public easily sidesteps racial difference strikes cosmopolitan citizens today as antiquated, backward logic, like Salem’s witch trial groupthink or Cold War domino theory. Still, nerds of color walk behind enemy lines every Wednesday to stay abreast of Jonathan Hickman’s Avengers or Geoff Johns’ Justice League; for many the local comic book shop’s mainstream customer base mirrors the standard-issue suburbia within biweekly superhero stories. Progressive integrationist comic fans poorly navigate the irony around which Disney and Time Warner craft business models: regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation, superhero comic fans wholly accept the antebellum identity politics of both the superhero concept and its target audience. Diversity does not sell superhero comics — nostalgia does, and this nostalgia hearkens back to postwar America, with its effervescent, bubbly nationalism, cleanly delineated racial hierarchies and obvious, unquestioned gender roles, even in private. For this reason, superheroes maintain their appeal to adolescent straight White males; everything in superhero narratives is designed to make Whiteness comfortable, to intensify the power of the privileged. Even nerds of color marvel when Captain America orders Sam Wilson to serve as his personal air support; computer generated scenes where Anthony Mackie’s sepia tones flit across Washington airspace spraying submachinegun rounds at unmasked Hydra agents while the winged brother evades rocket propelled death with hairpin banks at upchuck velocities satiate those who devolve superhero social justice into a Black actor’s screen time. Progress, for the superhero integrationist, requires nothing more than a regular census: survey the number of non-White, female, gay, lesbian, and transgender superheroes, and count the number of non-White, female, gay, lesbian, and transgender writers, artists, inkers, editors, and executives within the superhero comic industry. Tweet results with practiced outrage. Rinse and repeat. Qualitative analysis of minority portrayals violates the chirpy bluebird’s one-hundred forty character limit and does not engender comment.

Sam Wilson as The Falcon, played by Anthony Mackie, in

Captain America: The Winter Soldier

The only reputable progressive position on the superhero advises abandonment. The superhero concept’s narrow simplicity cannot possibly render human difference with substance or nuance. Corporate superhero fiction cannot dramatize the adrenal fear and visceral loathing police officers’ feel during traffic stops, sidewalk detentions, and no-knock warrants any more than it can judge the abject terror and furious anger the darker nation conveys through candlelight vigils, ‘I Can’t Breathe’ t-shirts, and Chris Rock’s unfunny selfies. “America begins in Black plunder and White democracy, two features that are not contradictory but complementary,” writes Ta-Nehisi Coates, senior editor of The Atlantic, in his landmark feature “The Case for Reparations“; in contrast, superhero comics lack all political theory more intricate than the Powell Doctrine. When Noah Berlatsky, writing at the Hooded Utilitarian on Static Shock, notes that the easy synergy between superheroes and law enforcement transforms Black superheroes into unwitting avatars for a modern mass incarceration state that translates public criminal justice into prison conglomerate profit, he should recall that urban post-Civil Rights Black elected officials championed draconian drug possession sentences with tough-on-crime rhetoric usually associated with Richard Nixon or Rudy Giuliani.

According to Yale Law School professor James Foreman, Jr., incarceration rates from majority Black cities “mirror the rates of other cities where African Americans have substantially less control over sentencing policy.” Black people, in the pulpit or the ballot box, can support robust and militaristic law enforcement initiatives deployed against their communities without tension, and those members of the darker nation with the financial stability and leisure time to engage electoral politics represent Black America’s most established, integrated, and conservative elements. What patience can veterans of color have with the dope pushers and domestic batterers and petty thieves and flamboyant pimps within their communities whose criminal enterprises depress already anemic property values? These old-school race men, with military precision and patriarchal inflexibility, assume the uplift of the race as personal responsibility; taught to kill by a country that hates them, taught to overcome prejudice with hard work and determination, the Black veterans who constitute the core of the Twentieth Century Black middle class personify bootstrap conservatism to chase economic inclusion, not revolutionary overthrow. This Black middle class, perennially called to account for a dysfunctional, systemically impoverished Black underclass left uneducated by dropout factory public education and unemployed by Silicon Valley’s outsourced manufacturing, loses its patience with both neighborhood criminals and municipal White political structures who concentrate drugs and violence and death in urban communities. Given this, Black elected officials these men chased the same militarized solutions to combat rising crime statistics during the 1970’s and 1980’s as their White counterparts, and municipal city councils stocked with pious Morehouse men and holy Spelman sisters proved no sturdy bulwark against dreaded million dollar blocks, no matter their local political success or state budget dependence. Unfortunately, when mostly non-Black superhero comic writers depict Black superheroes that support punitive carceral state solutions for minority criminality, no one references this history.

The problem here involves the superhero concept’s inability to envision non-White straight males as fully realized humans. The agony and the ecstasy of Black cultural and political complexity — from Jesse Jackson’s frustrated expletives in July 2008 over Barack Obama’s irrepressible moral centrism to Jesse Jackson’s joyous tears in November 2008 over Barack Obama’s irrepressible electoral victory — overloads the superhero’s straightforward make-believe. Black Panther, Black Lightning, Bishop, Mr. Terrific, Green Lantern, John Stewart, and U.S. War Machine: different power sets, different publishers, indistinguishable skin tones and identical personalities, all inflexible, assertive, upstanding old-school race men known more for quiet dignity than solo bombast, these characters present White male metahumanity shellacked with a moist black paste of burnt cork and water. I suggest that culturally authentic minority superheroes do not and cannot exist: all people of color receive from the superhero publishing industry replaces authentic and innovative characterization with race and gender drag. Sam Wilson’s instructive: these empowered Negro automatons unmask as superhero comics’ eternal sidekicks; they highlight White heroism’s astonishing brilliance and sacrifice race minority self-respect. This uncontroversial nostalgia justifies Black superhero inclusion in nearly every mainstream superhero team of note and illustrates an antiquated genre’s authorial recognition that the superhero concept cannot handle human difference. Every Black superhero is Will Smith drained of charisma, Denzel Washington without sex appeal, Barack Obama absent Michelle Robinson. All the same, all forgettable, all inhuman. Anonymous, nameless, Black. Other.

Michelle Rodriguez, captured by TMZ.com

When actress Michelle Rodriguez bellows “Stop stealing all the White people’s superheroes!” to a TMZ reporter, the initial backlash from superhero integrationists used digital condemnation and public shame to exact mob justice; within a day, Rodriguez’s pseudo-apology explained her disdain for superhero cross-racial casting as a desire to find multiple cultural mythologies Hollywood representation. Her critics remain unconvinced. I believe their skepticism toward Rodriguez’s perspective stems from the fact that everyone interested in posthuman and/or augmented, empowered human fiction in America today starts with seventy-seven years of superhero comic history as their main reference point. Imagine a future without the superhero. Imagine a future without the notion of a single person who can direct world history’s meandering river with unsanctioned activities that violate state sovereignty and ignore the rule of law. Imagine a future without the White male power fantasies that differentiate the superhero from the Gilded Age’s mystery men or Graham Greene’s quiet American. Imagine tomorrow as cosmopolitan cacophony, as an urban jungle gym where Asian Americans both support and oppose affirmative action, where Black Americans both support and oppose gay marriage, where gay men both support and oppose immigration reform, where Mexican Americans both support and oppose contraceptive mandates, where women both support and oppose religious freedom. Imagine tomorrow as remotely affected by today, and acknowledge that the superhero outlived his usefulness. The anachronistic Superman does not speak to individual aspiration, but to herd anxiety. Superhero films today comment upon unlimited power’s impossible paradox; Superman and his contemporaries personalize the unipolar American hegemon’s failure to establish justice and ensure domestic tranquility with Call of Duty martial advances at ready disposal via Raytheon and Lockheed-Martin. The superhero concept dramatizes White male power fantasy to express virile manhood through war and conquest; these figures of empire police unruly colonies populated with indiscernible aliens untouched by rational thought and Judeo-Christian order. Plot manifests from variable pacification success rates. The superhero’s great power lacks all sense of responsibility; it simply persists, unmoored from anything more complicated or complex than ‘punish the bad man who killed Mommy and Daddy’.

Adding melanin is no cure for unchecked militarism, fictional or otherwise; two Black Secretaries of State advised President George W. Bush before and during the Iraqi quagmire. Only rank racial tribalism exalts the need to view one’s own face in the corporate culture one consumes; this ethnocentrism leaves no room for critical examination of the superhero concept itself. Diversity initiatives in superhero comics fail because the superhero concept rejects human difference; every recent example of misogynistic cover art or fandom backlash against superhero cross-racial casting stems from general superhero creator/audience acceptance of the White male power fantasy as natural and normal. The term ‘Black superhero’ identifies a logical impossibility with a pejorative. Nerds of color who refuse to discard superheroes and wrangle superhero narratives with alternative reading practices to fit their politics and complement their group identities deny reality — there is simply no way to cast the Servant as Charles Stanhope.

Stanhope’s ethereal polish and command posture require chattel subjection. Reynolds’ portrait depicts a British nobility fueled by tortured adoration from broken children whose urgent pleas for respite from arduous toil and impassioned prayers for return to beloved parents go unheeded and unnoticed. The superhero is not a natural evolutionary step for reality or fiction; it’s a seventy-seven year old straight White male privilege delivery system. Those who believe superhero media’s reactionary excesses can be soothed with increased race, gender, and sexual orientation diversity wish only to substitute themselves for their oppressors, and combat nothing.

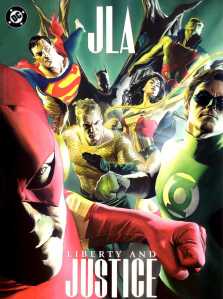

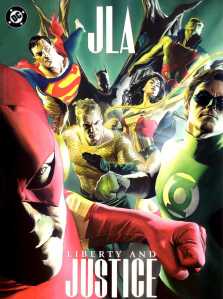

JLA: Liberty and Justice (2003), written by Paul Dini with art from Alex Ross

The DC Comics’ art from painter Alex Ross outlines the superhero concept today: in his JLA: Liberty and Justice, written by DC Comics’ animation legend Paul Dini, the Justice League characters feature smooth bulk and rounded brawn, adult muscle paired with primary colored paunches. Men are active but middle-aged, steely and determined, without care for clogged arteries or hypertension. Perfectly shaven with Brylcreem pomade and hip-hugging leotards, Ross’ work recalls Norman Rockwell’s America, where respectable Americans consumed conspicuously and segregation preserved decent communities. Like Matthew Weiner’s heralded Mad Men, Ross transports the audience to a postwar American economic success defended by flinty men with squinty eyes and absolutist ethics while readers enjoy safe genre futurism on every page. Batman’s cowl, tight enough to transmit facial expressions, locks into a perpetual scowl as he deconstructs villainous master plans. Ross’ Batman stands pudgy, comfortable; his grey contours testify to expense account living replete with three-martini lunches. Witness nostalgia as comic art, before Alcoholics Anonymous and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission wrecked the party.

Unknown artist, Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay and Lady Elizabeth Murray (1779).

Scone Palace, Perthshire, Scotland.

Ross’ antiquated Establishment action figures present the superhero self-image integrationists accept, defend, and then beg to subvert on the margins. It’s not enough. Brown palette swaps that color over George Reeves and Adam West recreations prove meager reparation for superhero comic whitewashing. This too, ignores history. Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray appear together in a portrait from the late Eighteenth Century, friendly, enigmatic, and equal — to a point. Dido, in a Indian turban plumed with ostrich feathers and exotic silver satin, enters posterity an exaggerated Oriental, a perpetual foreigner totally without definition unless visually justified by non-Western affectations. The unknown portraitist does not imagine smiling brown Dido, a free English woman born from British imperialism, with the prim reverence afforded her cousin and countless other noble British ladies. The skin still matters. Today, art historians’ alternative analysis of Charles Stanhope, third Earl of Harrington, and a Servant interrogates the time-lost lives behind servile brown eyes, and speculates that this tortured gaze scans something past Stanhope’s shiny armor. Perhaps the Servant spies tomorrow, Jubilee, a new birth of freedom. We can never know. To my mind, Reynolds’ portrait allows superhero integrationists a prophetic metaphor: however difficult, look past the intended narrative of one’s age. Imagine tomorrow. Envision a world where your humanity depicts more than a detailed frame for someone else’s daydream.

_________

[i] “An Answer to the Question: ëWhat is Enlightenment?'” — Immanuel Kant, 30 September 1784

[ii] Esther Chadwick, Meredith Gamer and Cyra Levenson, Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain, exhibition wall text, Yale Center for British Art, 2014

[iii]Stanhope sat for Reynolds two years following his regiment’s deployment to Jamaica to battle back French incursion that threatened Britain’s largest slave colony. — Esther Chadwick, Meredith Gamer and Cyra Levenson, Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain, exhibition wall text, Yale Center for British Art, 2014

_____

The entire roundtable on Can There Be a Black Superhero? is here.