A perhaps unlikely, but nevertheless useful starting point for discussing cartooning is classical art—not seen as its polar opposite, but rather as its elevated obverse, similarly aspiring toward truth.

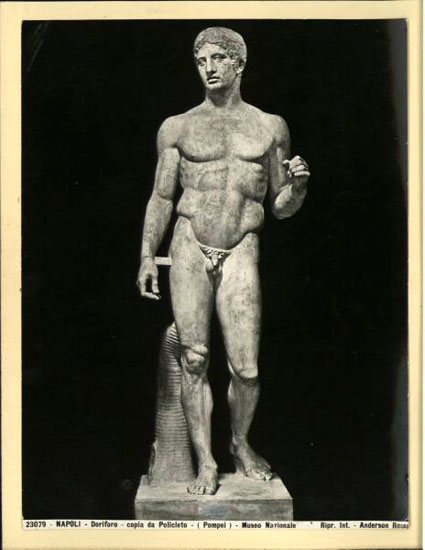

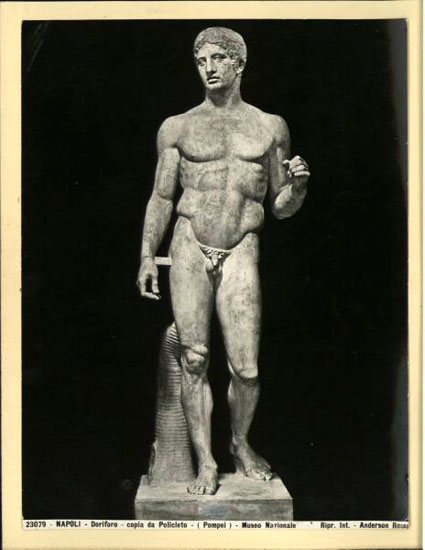

Polykleitos’ famous Doryphoros, or spear-bearer (c. 450-440 BC), as it survives in a Roman copy, is a good example. Acutely aware of the particulars of human anatomy, the sculptor distilled from empirical study a now-lost canon of perfect proportion, which applied mathematical principles to the creation of beautiful form. Neither the body, nor the face of the statue appear to us as an unadorned depiction of a man, but nevertheless convinces us of its truthfulness to nature through the sculptor’s evident, careful attention to the human form. It works as a rational prototype unto which we can easily map ourselves.

We learn from Pliny that the Greek painter Zeuxis (late 5th century BC) had similar concerns. Famously having to paint Helen of Troy, he took from five individual models their most beautiful traits and combined them to render that historic beauty. His painting, then, was an abstraction from nature used to project a recognizable prototype. An approach that has as much to do with Aristotelian cognition as it does with Platonic idea.

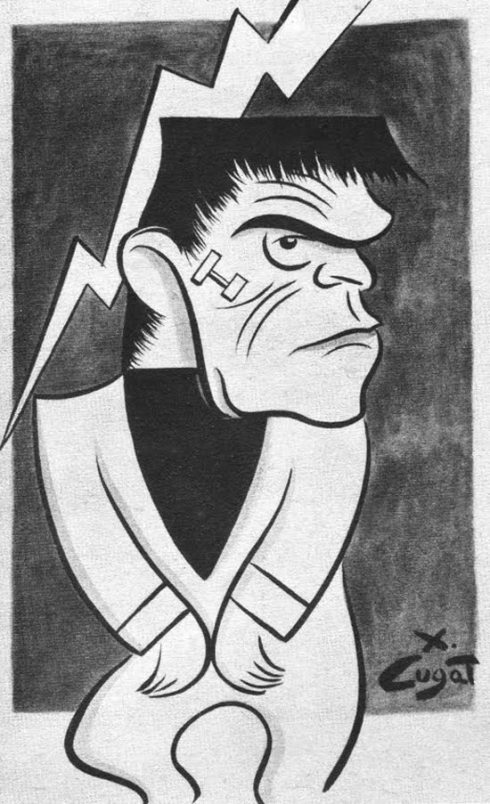

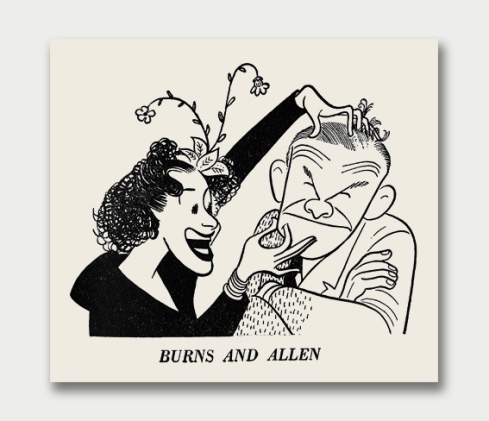

In his groundbreaking Essai du physiognomonie of 1845, the cartoonist Rodolphe Töpffer describes cartooning as a way of portraying the soul of the individual through the condensation of traits into archetype. He further noted that it does not require systematic study of nature, but rather works through a system of almost sign-like notation, immediately identifiable to us.

Sound familiar? To be sure, there are important differences between classic and cartoon form, and the latter has indeed been regarded as an irrational mockery of the former through the modern age, but their fundamental endeavor seems to me strikingly similar. One deals with rational prototype, while the other focuses on profane archetype; one necessitates a detailed understanding of nature’s principles, while the other requires a good eye for human physiognomy and behavior.

Essentially, however, they are both idealist endeavors, distilling experience into visual forms, and thus appealing to what is described by neuroscience as our understanding of phenomena through prototypes synthesized in our brain, into which new experiences are integrated and thereby processed.

Essentially, however, they are both idealist endeavors, distilling experience into visual forms, and thus appealing to what is described by neuroscience as our understanding of phenomena through prototypes synthesized in our brain, into which new experiences are integrated and thereby processed.

Töpffer was writing at a time when the cartoon was more pervasive in society than it had ever been, but as a way of drawing it is as old as representational mark-making. In the renaissance, the kind of notational, linear, and exaggerated drawing today associated with it, appears in marginalia, on the backs of canvases, and in other places one would expect to find doodles.

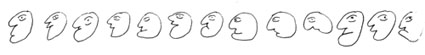

A compelling example is the suite of heads on the back of Titian’s so-called Gozzi Altarpiece in Ancona (c. 1520). Surely drawn by the master, and probably his assistants, when the huge panel was still in the workshop, they run the gamut from naturalistic to grotesque, and in places approximate minimalist abstraction. And several of them, most notably the female profile on the right, recall classical form.

Leonardo, Profiles of an old and a young man, red chalk, Florence, Uffizi

The most famous doodler of the age was, of course, Leonardo, who throughout his life would

populate the margins of his manuscripts with a variety of

grotesque heads. An outgrowth of investigations into human morphology and the spectrum of human emotions not unlike Töpffer’s, they embody his notion that an artist would invariably express his self, resorting to its subconscious typology if his attention veered from manifest nature.

It is surely no coincidence that Leonardo’s two most repeated heads, the grotesque so-called ‘old warrior’ and the beautiful young ephebe, invoke classical models—the former is adapted from portraits of the Roman Emperor Galba, while the latter clearly reflects the Hellenistic ideal of beauty. As with Titian, it seems a natural impulse on the part of the artist, reminding us of the strategies of simplification integral to classical art, and of the fact that all art, from the exalted to the grotesque, seeks a synthesis of idea and form in its search for truth.