Preface.

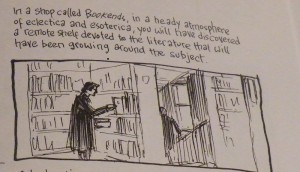

So by way of a preface, you need to know that even though people talk a lot about all the comics references and history, in-jokes or savvy interpretation of the comic medium’s trajectory, Alec: How to Be an Artist works as a narrative even if you don’t really know what and who all those comics and comics people are.

Not that I think there’s anything wrong with the comics references and in-jokes. I just don’t get most of them more than cursorily. They don’t carry the weight of familiarity for me that I’m sure they do for most of you. I acknowledge that this surely means I’m missing something…

But I absolutely don’t feel that the book is some cliquish thing that nobody but a card-carrying life-long comics geek is allowed to read and appreciate. There’s a lot here for a reader like me – a reader whose aesthetic commitments have always been to prose fiction. Much of what’s here is close to the delights of prose narrative: evocative descriptions of environments and social interactions, ordinary familiar emotions, a strong sense of voice and narrator identity. Artistic enjoyment, and even ambition, aren’t only found in tightly managed formalist perfection. But that’s not to suggest, though, that there’s nothing of formal interest. There’s very sophisticated structure here. More on all that in a bit.

Not knowing those comics references particularly well just lets them fade a little into the background, even in this very comics-centric section, and makes all the other things that are happening more prominent. And those other things are very satisfying. And this post is about the other things.

A little more preface.

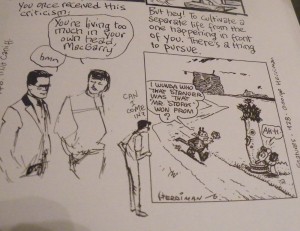

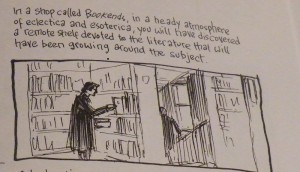

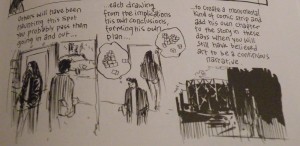

Well, ok, not all of the other things. There’s so much. There’s a lot of doubling, starting with the second person but perhaps most interestingly the use of quotation (mostly visual). There’s a lot about attachment and alienation. The identity of the artist is intentionally faceted and slippery (“You”, Alec, Campbell). I’ll come back to this, but this is one reason why I disagree with the notion that the narrative is solipsistic: the impracticality, even pointlessness, of solipsism is one of the book’s themes. Solipsism is alluring, but impossible. Art comes from other people, and other art, and from experiences in the world. That’s why peer groups – historical predecessors and colleagues — and the artistic culture and industry are so important to this narrative.

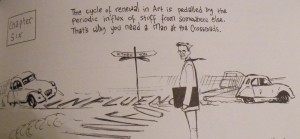

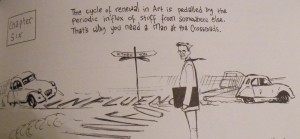

For me, the central theme of How to Be an Artist was this question of influence, the in-betweenness of autonomy and beholdenness: at the crossroads,

on the turnpike.

What do you buy when you sell your soul to the devil? You buy knowledge of the world. What is the price? The possibility of believing that nobody else matters.

What it means to be an artist is balancing on the knife edge of solipsism and selling out: perspective has to come from inside your head, but it must be meaningful to those outside. This book doesn’t ignore that — it’s about that. It may not be about how to be a successful artist, but it’s certainly about how to be a wise one. And it manages to be all those things, all the thematic sophistication and formal sophistication, while still being really atmospheric and descriptive and just plain pleasurable.

But I’m not going to talk about most of that though. Ok, a little bit about the pleasure. Maybe somebody will discuss the theme of influence. Maybe I’ll write another post.

But right now I’m going to talk about grammar, because with most comics there’s nothing to talk about. And Campbell’s prose is gorgeous.

Part 1.

Second person singular. Future perfect tense.

So he says, but he doesn’t actually stick with it throughout, despite the intro: it’s in plain old future most of the time. But the instincts are better than the rule: the shifts between future and present and the occasional actual past are vastly more effective than rigid future perfect would be. The use of the future perfect in the places he does use it, though, is sufficient to establish the bizarre temporality that that tense suggests, and that bizarre temporality saturates the rest of the section.

Lacan once noted that crazy people cannot think in the future perfect tense (the exact quote is that the emergence of identity is “a retroversion effect by which the subject becomes at each stage what he was before and announces himself — he will have been — only in the future perfect tense.”) Perhaps it’s due only to the power of suggestion, but I found the perspective of this book incredible sane.

The future perfect tense is powerful for its active assertion of inevitability and its blurring of passive and active. Technically, it suggests a point in the future prior to which a given action will have been completed: “I will have washed all my clothes by the time you get here.”

But in Campbell’s hands here, it refers to actions that have already been completed in the past, so the “present” tense of the grammar is the past tense for the reader. The result is a doubling of the vantage point and of the time of the narrative: the future perfect tense conveys the author’s narrative awareness of history while leaving intact the position of the character who has not yet experienced that history.

There is the time of the “you” – asserting and anticipating the future events. There is the time of the author, who knows what those events will be because he is already in the future that they point to. In other words, there is the time of the main character of the prose, and the time of the authorial voice.

But because this is comics, there is also the time of the pictures, which is (generally) the literary present. Not just because, often, the dialogue within a panel is in the present tense, but also because the time of an image, from the perspective of the image itself, is always the present, the moment present in the space that it represents.

This is a comic where both image and prose are fully active, fully explored. The full range of temporality from images, the full range of temporality from prose. That allows the time experienced by the narrative subject to be not just doubled but tripled: past, future, and present, all together, all represented simultaneously and equally.

Not only do I find this temporal pluralism quite satisfyingly nuanced – there’s something comfortingly unblinkered about such a temporal panopticon – as a formal structure it’s so much more ontologically fascinating and narratively flexible than the more mechanistic notion of sequential panels representing time as space. When prose is left behind, or replaced by “comics dialogue” that does not make full use of the toolkit of prose, images enforce a hegemony of the present. This causes a formal insistence on the presence of the panels that makes those kind of comics very insistently material and, I think, makes the immersive qualities of great literature harder to achieve. Comics are often Baroque, but they don’t have to be.

Much of the conceptual sophistication here comes from this recognition of how present to itself visual representation is. By choosing a verbal tense that essentially puts brackets around the present tense (the future perfect is both future and past), the time of the prose wraps the time of the images and breaks the hegemony of the visual present – you get all the immediacy of the visual present, but without its temporal solipsism. (Meaning “the time of the image is all that exists to the image,” not the psychological solipsism Vom and Noah mentioned.) The narrative vantage point is that of all possible times at the same time.

This is something comics can do that neither visual art nor prose can do alone. Because grammar is linear, it’s nearly impossible to get all possible times at the same time. You can grammatically nest the tenses, but you can’t get them all simultaneous, and if you’re not careful, tense shifts can become grammatical errors. But because images are always present to themselves, visual art always conveys a strong sense of the moment. In comics that emphasize sequentiality, you always have traces of what Heidegger called a “succession of nows.” When the prose and the images are more equal, each helps the other out of the ontological double bind, allowing for the native temporalities of both modes of representation to operate in concert.

(I rush to say, in the midst of all this grammar that’s about to become philosophy, that Campbell, unlike your present critic, gets all this ontological niftiness into his book effortlessly, leisurely, without sacrificing the liveliness and flow of the narrative or the believability of the characterization or the visual pleasure to the formal device. This is masterful. I’m sure I’ll get the criticism that none of what I’m talking about is the point of this book, and it doesn’t have to be. But the fact that it happens makes the book even more pleasurable for me.)

Heidegger in fact rejected the notion that time is an “uninterrupted succession of nows,” calling that notion “vulgar.” Instead he posited that the past, present, and future are unified, and that that unity is “ecstatic” – the ecstasy of the “potentiality of being.”

It makes sense that autobiography should be concerned with the ecstasy of the potentiality of being. There’s no question that the narrative arc of How to Be an Artist follows the typical frustrations that accompany putting artistic creativity in the service of earning a living: including the necessity of spending a lot of time in your own head, as other commenters here have noted. Being an artist is about being yourself too much and not enough. But I don’t think Campbell is unaware of this. I think it’s an intentional representation of those aspects of the creative life.

And perhaps that’s what comes across more when the comics references fade into the background. Campbell’s relationship to comics feels like my relationship to prose books. It’s affection, not fetish — but it’s also his job. He can’t exactly stop thinking about them. To be an artist you have to inhabit doubled worlds — the beloved world of books and the much less beloved world outside of books. Although someone who loves art but does not want to make it can escape into fictional worlds, and we can expect people who have no need for creativity to be utterly pragmatic and realist in their dealings with others, inhabiting both interior and exterior worlds is essential if you want to make art rather than consume it.

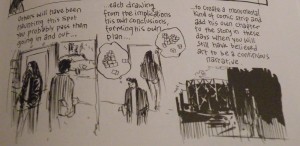

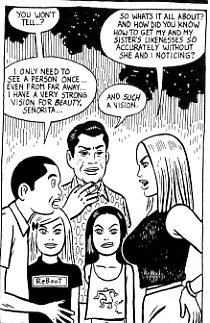

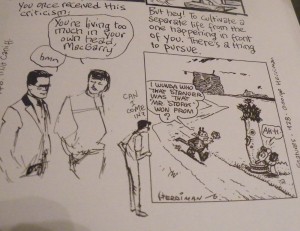

My favorite panel in How to Be an Artist gets at this directly.

Not sure I would have chosen to visit a place inhabited by a crazed brick-throwing rodent, but the image of “knocking on the door” of a fictional reality is utterly charming. There’s a difference between a self-aware introversion — one that has full access to the imagination — and solipsism, and for me at least, the formal structure and perspective of this work undercuts the notion that the introversion slips into solipsism. It’s hard to imagine a meaningful “life of the mind” that doesn’t happen inside the mind. After that panel is this extraordinary passage, which I’ll transcribe in prose to let how well-wrought it is come across more directly, although it’s more effective with the images (which among other things, change the rhythm):

But hey! to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you. There’s a thing to pursue.

An inside life, where Fate talks to you, sometimes in the charming tones of a girl singer with old Jazz bands.

Othertimes in a naive wee voice in which all things are still possible.

Conceit is no criticism here in the realm of the spirit as it is in real time where your heroes are long gone.

On an airfield in China, Terry Lee is still kissing Jane Allen goodbye

In Gasoline Alley, Skeezix is having his midlife crisis

In a vast silent Arizona desert, a Coconino moon pours out molten silver…

It drips on Alec MacGarry, asleep at the turnpike

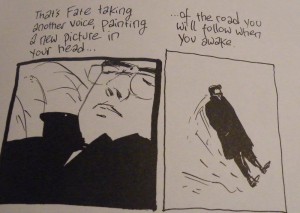

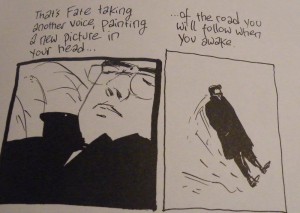

That’s Fate taking another voice, painting a new picture in your head

of the road you will follow when awake.

“Your heroes are long gone” — in the past.

“Still kissing Jane Allen goodbye” — in an eternal present.

“The road you will follow” — in the future.

This is the “potentiality of being” specific to the artistic mindset: “to cultivate a separate life from the one happening in front of you.” That describes an ecstasy of art, and part of the brilliance of this book is the recognition of how you find that ecstatic potential in the mundane life story. But the wisdom of that temporal panopticon is the point that being a successful artist requires saturating the life story with that ecstasy, so that the experience of the present is constantly imbued with the past and future, the “Picture in your head of the road you will follow when awake.” That ecstasy is something Campbell does extraordinarily well.

Part 2.

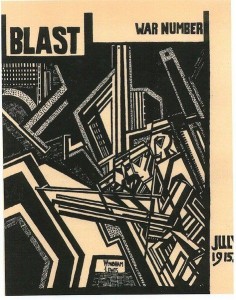

Art comics culture encourages a certain fetish of the image, especially the semiotically loaded image – or rather the related idea that pictures can take over the functions of narrative normally carried by words, that you can “read” images to construct narrative. Many of the most lauded art comics are works that pack the images with parsability – visual metaphor, visual narrative, symbolism. Inattentiveness to this often gets treated like a failure of literacy and images that aren’t packed to the semiotic breaking point become tainted as “mere illustration” (to quote from here).

But practically speaking, the result of this emphasis is a reduction of narrative to the barest bones of signification, because one of the things you lose when the images are as tightly meaningful as they generally are in the School of Heightened Visual Signification is the lushness of leisurely atmospheric description, which is a tremendously pleasurable part of fiction.

Witness this particularly visual segment from a book by a particularly visual prose writer, Don Delillo, (from Part 5 of Underworld), which I’m going to quote at its full lengthy length:

We were about thirty miles below the Canadian border in a rambling encampment that was mostly barracks and other frame structures, a harking back, maybe, to the missionary roots of the order — except the natives, in this case, were us. Poor city kids who showed promise; some frail-bodied types with photographic memories and a certain uncleanness about them; those who were bright but unstable; those who could not adjust; the ones whose adjustment was ordained by the state; a cluster of Latins from some Jesuit center in Venezuela, smart young men with a cosmopolitan style, freezing their weenies off; and a few farmboys from not so far away, shyer than borrowed suits.

“Sometimes I think the education we dispense is better suited to a fifty-year-old who feels he missed the point the first time around. Too many abstract ideas. Eternal verities left and right. You’d be better served looking at your shoe and naming the parts. You in particular, Shay, coming from the place you come from.”

This seemed to animate him. He leaned across the desk and gazed, is the word, at my wet boots.

“Those are ugly things, aren’t they?”

“Yes they are.”

“Name the parts. Go ahead. We’re not so chi chi here, we’re not so intellectually chic that we can’t test a student face-to-face.”

“Name the parts,” I said. “All right. Laces.”

“Laces. One to each shoe. Proceed.”

I lifted one foot and turned it awkwardly.

“Sole and heel.”

“Yes, go on.”

I set my foot back down and stared at the boot, which seemed about as blank as a closed brown box.

“Proceed, boy.”

“There’s not much to name, is there? A front and a top.”

“A front and a top. You make me want to weep.”

“The rounded part at the front.”

“You’re so eloquent I may have to pause to regain my composure. You’ve named the lace. What’s the flap under the lace?”

“The tongue.”

“Well?”

“I knew the name. I just didn’t see the thing.”

He made a show of draping himself across the desk, writhing slightly as if in the midst of some dire distress.

“You didn’t see the thing because you don’t know how to look. And you don’t know how to look because you don’t know the names.”

He tilted his chin in high rebuke, mostly theatrical, and withdrew his body from the surface of the desk, dropping his bottom into the swivel chair and looking at me again and then doing a decisive quarter turn and raising his right leg sufficiently so that the foot, the shoe, was posted upright at the edge of the desk.

A plain black everyday clerical shoe.

“Okay,” he said. “We know about the sole and heel.”

“Yes.”

“And we’ve identified the tongue and lace.”

“Yes,” I said.

With his finger he traced a strip of leather that went across the top edge of the shoe and dipped down under the lace.

“What is it?” I said.

“You tell me. What is it?”

“I don’t know.”

“It’s the cuff.”

“The cuff.”

“The cuff. And this stiff section over the heel. That’s the counter.”

“That’s the counter.”

“And this piece amidships between the cuff and the strip above the sole. That’s the quarter.”

“The quarter,” I said.

“And the strip above the sole. That’s the welt. Say it, boy.”

“The welt.”

“How everyday things lie hidden. Because we don’t know what they’re called. What’s the frontal area that covers the instep?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know. It’s called the vamp.”

“The vamp.”

“Say it.”

“The vamp. The frontal area that covers the instep. I thought I wasn’t supposed to memorize.”

“Don’t memorize ideas. And don’t take us too seriously when we turn up our noses at rote learning. Rote helps build the man. You stick the lace through the what?”

“This I should know.”

“Of course you know. The perforations at either side of, and above, the tongue.”

“I can’t think of the word. Eyelet.”

“Maybe I’ll let you live after all.”

“The eyelets.”

“Yes. And the metal sheath at each end of the lace.”

He flicked the thing with his middle finger.

“This I don’t know in a million years.”

“The aglet.”

“Not in a million years.”

“The tag or aglet.”

“And the little metal ring that reinforces the rim of the eyelet through which the aglet passes. We’re doing the physics of language, Shay.”

“The little ring.”

“You see it?”

“Yes.”

“This is the grommet,” he said.

“Oh man.”

“The grommet. Learn it, know it and love it.”

“I’m going out of my mind.”

“This is the final arcane knowledge. And when I take my shoe to the shoemaker and he places it on a form to make repairs — a block shaped like a foot. This is called a what?”

“I don’t know.”

“A last.”

“My head is breaking apart.”

“Everyday things represent the most overlooked knowledge. These names are vital to your progress. Quotidian things. If they weren’t important, we wouldn’t use such a gorgeous Latinate word. Say it,” he said.

“Quotidian.”

“An extraordinary word that suggests the depth and reach of the commonplace.”

His white collar hung loose below his adam’s apple and the skin at his throat was going slack and ropy and it seemed to be catching him unprepared, old age, coming late but fast.

I put on my jacket.

“I meant to bring along a book for you,” he said.

Now, imagine a version of that passage in comics. First imagine it drawn by Chris Ware – and then imagine it drawn by Eddie Campbell. In my imagination, Ware’s version would undoubtedly involve a quite detailed technical diagram of a shoe, as arcane knowledge is a bit of his bailiwick, and he would surely be able to capture the intensity of the thematic point, the buildup to the “gorgeous Latinate word.” It would probably, in fact, be an even more pointed buildup.

But much of the realism and atmosphere of that scene come from the rhythm of the speech and the texture and atmosphere of the descriptions. And that’s separate from the metaphors. Even though visuals are suggested, the visuals aren’t the point. The narrative trajectory is only part of the passage’s impact: that’s its significance, not its effect. Campbell’s grasp of and appreciation for prose makes me believe he could capture the visceral tactility — the awareness of how things feel and look, as well as the description of how they feel and look — and the dialogic humor of the passage as well. Prose literary narrative doesn’t just convey emotion and story; it also suggests imagery and demarcates space and evokes setting and represents the mental experience of having experiences — and it accomplishes those things in ways that are quite different from the ways they’re accomplished in primarily visual narrative. Since comics in fact has a quite native place for prose writing to occur, letting cartoonists off the hook for doing it well it is significant critical failure in my book. Campbell does write prose extraordinarily well, and it makes all the difference.

By not rejecting real honest-to-God prose (as opposed to “comics dialogue”), by letting his pictures sometimes just be about gesture or mood or setting and the parts of literary meaning that traffic in images and visuals, Campbell gets to something that feels so much more like visual literature than many other cartoonists, who are doing something closer to “literary art.” His drawings are atmospheric, suggestive, not illustration but illustrative. And great literature is all of those things.

That’s why “mere illustration” is so terribly wrong, and why the hegemony of symbolic and metaphorical and even narrative images as a substitute for really outstanding prose writing does so much violence to the potential of the form.

It seems like atmosphere and illustration are broadly associated with the pulpier genres of comics, with genre comics rather than art comics. But there are literary ways to handle atmosphere and description too, and it matters that comics can do this, can be literary in this particular way. It’s an achievement, and it doesn’t matter that it’s not pushing the envelope of visual semiotics. It’s literature. It’s doing interesting literary things. It’s allowing visual imagery and literary imagery to overlap and converse.

I hesitated before writing this, because after a year of writing here I feel like a lot of people will take this as my selling Campbell short, not paying attention to the art or the potential of art or giving the art enough autonomy. I’ve been chastised so often for wanting comics to be ambitious in ways that are familiar and beloved to me from prose literature, an ambition that does not require a baroque disjointed reading but allows immersion, sophisticated and subtle and smart without getting tangled up in so many formalist visual tricks that they feel stiff and micromanaged. The more packed with significance a picture is, the less those things can come to the fore. This argument is often made by saying that comics should do something unique, that they don’t need to be like literature because they can be their own unique thing. But for me, the experience of reading Campbell’s writing — and I strongly prefer the ones where he’s the writer although I like his art when he’s not — is unique: it’s just a unique form of literature, rather than a unique form of something else that really isn’t literature at all.

Comics at their best are a tightened and compacted form: the classic example is always Peanuts, with its ability to cull away all the chaff and leave only the essential bits. Many comics where images carry the narrative tighten by reduction, because you just can’t pack as much into an image as you can into an extended prose passage, and you can only repeat the image so often for subtle effect before you’ve got a flip book instead of a comic. Comics that use that strategy reduce the narrative to the most essential elements, and then convey those elements through the images. There can be extraordinary power in that approach.

But Campbell’s stories, because he doesn’t cast aside prose, can condense without reducing. The description and atmosphere and even rhythm that takes so much room to establish in prose can easily be encapsulated into a single evocative frame. I don’t mean that this is all Campbell’s panels do; sometimes they are packed with signification, but sometimes they aren’t, and because they’re working with prose rather than instead of prose, it becomes an artistic choice rather than a requirement for the narrative flow. The shape of the narrative is changed from prose to comics: the form is compacted, but the narrative itself is as big and rich and full as a full-fledged novel. Campbell’s books are bigger on the inside than the outside. And I think that’s what art is all about.

Finale.

By way of a postscript, my friend Chris, whom regular readers may remember as my interlocutor in the Swamp Thing Roundtable, once got a letter published in The Comics Journal back in April of 1997. I’ve reprinted it below.

“I was extremely saddened to learn of Stan Drake’s passing. He was truly one of comics’ finest craftsmen, as clearly shown by the panel you folks ran with his obit. Who could forget The Heart of Juliet Jones, that great schizophrenic-vigilante strip he collaborated on with scripter Doug Moench and inker Klaus Janson during the early ’80s?

“I only regret that you couldn’t find the space to run a panel or two of his later, more mature work on titles such as Elektra: Assassin and Stray Toasters. Ah, well…”

The Comics Journal titled it “Ouch.”

________

Update by Noah: The entire Campbell roundtable is here.