Because it kicks ass, I’m reprinting and highlighting Caro’s comment from this post.

To Darryl’s point: for me, “divorcing comics from its cultural history” isn’t about being embarrassed about comics’ history so much as it is recognizing that “comics history” is neither sufficient cultural context for already existing comics nor necessary cultural context for yet-to-be-created ones.

The idea that comics history is both necessary and sufficient — I could put in jargony terms and say that it feels like a caving in to historical determinism. But it’s really more that it gives me no way in.

What L. describes — she says that about creators, but I feel that as a critic too. On the whole, very few comics keep me awake at night the way literature and criticism and theory and Godard films and conceptual art do — not because those things are better than comics-history-inspired comics, but because those are the things I like, and they’re having a different conversation than comics has historically been having.

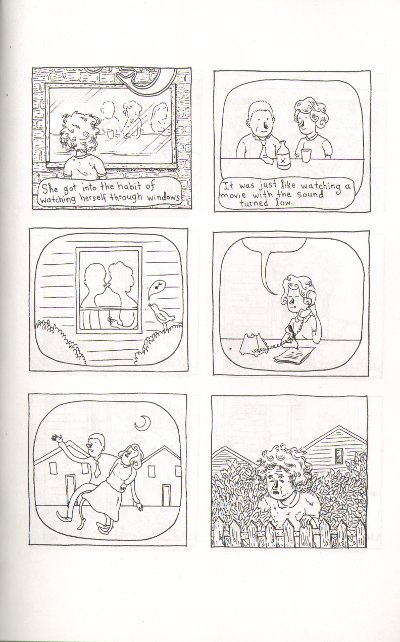

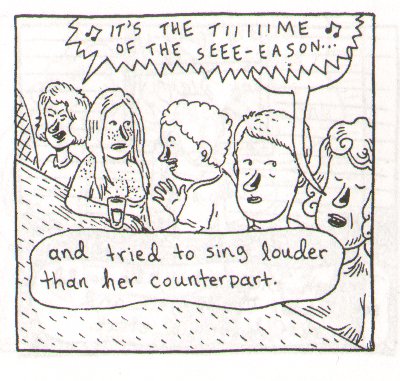

I pay attention because occasionally, a comic comes along that really intervenes in the stuff I care about (like Feuchtenberger, or the stuff Jason just linked to!) and on the occasions when that has happened, it’s been so extraordinarily worthwhile that it’s worth keeping an eye out.

But for many things, it’s hard for me to muster the enthusiasm to do a real piece of criticism, because the book just isn’t doing anything to keep me awake. No matter how cool the tricks with comics history gets, no matter how nuanced the conversation, it’s just never going to keep me awake, because I’m interested in DIFFERENT histories — pop art, experimental fiction, 20th century theories of language and representation, artistic constructions of subjectivity. I think it’s wrong to say that comics can’t become part of those histories, now, even though they’ve historically not been. (Or, to return to the jargon, how can we expect the dialectic to work without antithesis?)

I absolutely don’t mean that comics-history-inspired comics aren’t doing very interesting things with that history. I don’t mean they shouldn’t exist, or that they’re “less” in any way than other comics. It’s just that, for me, who has no history with comics, comics history can’t on its own provide a foundation for challenging, provocative, mind-changing art, so for comics to challenge me, provoke me, and change my mind, I need there to be SOME comics that deprioritize the specific history of comics in order to engage more actively with those other histories.

That’s why the strength of the term “divorce” feels right to me. Comics’ relationship to their own history often feels like a marriage where one partner’s potential is being really held back in order to protect or build up the ego of the other partner. And I like comics better than I like comics history, so I say “girlfriend, leave!” Comics > cartooning.