My friend Chris loaned me his beloved, carefully encased in plastic, original issues of the full Alan Moore run of The Saga of the Swamp Thing for this roundtable. We’ve been talking about it off and on for the last couple weeks. This post is compiled from the highlights of our conversations.

My friend Chris loaned me his beloved, carefully encased in plastic, original issues of the full Alan Moore run of The Saga of the Swamp Thing for this roundtable. We’ve been talking about it off and on for the last couple weeks. This post is compiled from the highlights of our conversations.

Chris: Well, they weren’t carefully encased in plastic.

Caroline: No? You couldn’t prove it from how hard they were to get out.

Chris: I really do hate plastic bags. I typed a mini-rant that was totally off-topic, but you know, I’m not that much of a geek.

Caroline: You couldn’t prove it from this blog post.

Chris: Ha ha ha. Very funny.

Caroline: Well, I haven’t gotten them back in the plastic yet, but thanks for loaning me your Swamp Things.

Chris: You’re welcome. Did you like them?

Caroline: I did!

Chris: Really? I didn’t expect that. I never once thought about trying to hand you any Alan Moore other than From Hell.

Caroline: How come?

Chris: Well, they’re just pretty much straight-up genre work for the most part, albeit a kind of elevated version of it.

Caroline: Hey, I like genre!

Chris: You like SF.

Caroline: And romance!

Chris: OK, yeah, but you hate fantasy, and I’ve never heard you say anything about horror.

Caroline: Well, ok. That’s true. Sort of. I don’t absolutely hate fantasy and horror; it’s just that I don’t much like their post 19th-century incarnations, except when they’re really intended for kids. I like them fine in mythology or actual Arthurian legend, or Mary Shelley.

Chris: When I’ve steered you toward stuff, I’ve gravitated more toward the art than the genre side. Genre comics are books where the whole point is “this book exists to be liked,” and you tend to want more than that.

Caroline: Well it’s no secret how much I love art fiction. But I just read genre fiction differently from how I read art fiction. I’m less intellectually interested in it but it’s still pleasurable.

Chris: I guess I’m surprised you liked Swamp Thing because a) I didn’t think you were interested in genre fiction more than historically, and b) I think the problematic thing about SotST is that it kind of smacks of trying to redeem genre. You know: “World’s Best Swamp Creature Comic.” Everybody seems to struggle with “b”, and I didn’t think you would be any exception. But I didn’t think you’d get past “a.”

Caroline: Well, here’s the thing. I’m sure one of the reasons I was able to like this one is that the activation energy was very low, largely due to the prose doing the heavy lifting on the story. I could skim it. I can’t skim an art comic. I’m not sure anybody can really skim an art comic, at least not while actually “reading” it.

When I read genre, it’s for relaxation and the point is just to get swept along and enjoy it, not to really wallow in the details. I guess I read it like most people watch tv. Remember that reading for details is my job. So when I read for entertainment the whole point is not to worry as much about details, except the ones that I need to understand what’s going on.

So I especially like genre fiction that really wallows in familiar tropes. If it gets experimental or tricky, I want it to be something with a lot of metaphorical sophistication, really more art fiction that’s playing with genre tropes than “well-done genre.” I don’t have the energy for some really thick plot-heavy worldbuilding thing, because then I have to pay a lot of attention for a payoff that essentially is only a decent story. And mostly I’m not interested in thinking very hard about stories. I kind of expect a story to resonate enough that I don’t have to.

Chris: Hm. I can see that.

Caroline: And hell, this Swamp Thing is the uber-incarnation of “wallowing in familiar tropes.”

Chris: I was just going to say…

Caroline: I could read through it pretty quickly, enjoy the atmosphere and feel grounded enough to know what the story was, but not really be obligated to dig into the details.

Chris: Although, “wallowing in tropes” applies mostly toward American Gothic, which has this artificial structure imposed on it…

Caroline: I don’t know about that. I think Moore takes tropes from different genres throughout. The romantic triangle with the jerky husband is very much a trope, then Abby falling in love with her best friend. There are science fiction tropes throughout, and some elements from noir interspersed, especially in Constantine. Everything was quickly recognizable. I didn’t feel like anything was particularly new.

Chris: Let me talk to your prose observation…You like it because it’s prose for all intents and purposes, but you said you did like the art, yes?

Caroline: Absolutely. It’s very lush and atmospheric. I love the colors.

Chris: Does the art just provide atmosphere? Does it contribute in any meaningful way, or is it just a substrate for Moore’s prose?

Caroline: Well, atmosphere is a big part of genre isn’t it?

Chris: Yeah.

Caroline: I think it mostly provides atmosphere and texture, but I think that’s essential to good genre. It happens to be the part that’s often not very effectively conveyed in prose, and art gets at it very efficiently. I thought this art was smart and mostly very consistent at a high-level with Moore’s aggregation of tropes. I’d probably even say the art overall was better quality than the writing; it was a huge part of the impact of the book.

Chris: I think one of the interesting things about Swamp Thing in this respect is that it is a collaboration. Bissette-Veitch-Totleben were pals and studiomates, so there was a more seamless union than you usually get. Generally penciller/ inker breakdown is just assembly line to grind out more product faster. This team, all of them were pretty simpatico.

Caroline: That makes sense. There was a tremendous difference in the issues that had a different art team: they weren’t nearly as alive. They really didn’t have anything like the same emotional texture. But I guess what I’m saying is that I wasn’t really relying on the art at all to make sense of the book.

From my perspective, as a very skilled fiction reader almost entirely unfamiliar with mainstream comics, the division of labor here – meaning the narrative labor, not the collaborative work of creating the book – is very sensible and practical: the words did the narration and dialogue, the stuff words are really good at, and the pictures set the atmosphere and the tone and the mood, created the emotional texture. And the prose is just really competent: the prose techniques and tropes were very recognizable, and that was a really easy way into the story.

And an easy way in was really essential for me as a first-time reader. The few times I’ve picked up mainstream comics before, I’ve immediately had a very strong sense of “this was not written for me.” There’s a hint of “go read these other things and get a grounding in this tradition, then come back and read this,” which requires a commitment to genre comics that I don’t have. That wasn’t here at all in this book, despite the strong genre tropes, because they were so immediately and totally recognizable from their fiction counterparts.

Chris: I think the art really does contribute maybe more than you’re implying, because the team was so sympathetic, both to what Moore was doing, and to the genre in general. I think Bissette was overjoyed to be associated with “Best Swamp Creature Comic Ever,” without irony or embarassment.

So if SotST had been drawn by whomever was just hanging around the DC offices looking for work, I don’t think it would have been the same, no matter what the caliber of writing. Steve Bissette in particular is BIG into horror, and I think his enthusiasm was kind of a driving force in a lot of ways.

Caroline: I don’t disagree with that. I’m not so much trying to downplay the art as explain how the prose worked for me. My point is just that I didn’t really find myself reading the art much. And really, my overall response to the comic wasn’t that the horror genre was so dominant.

Chris: Even in the art?

Caroline: I saw a lot of visual tropes from horror in the art, but there were so many other genres mixed in there that no single one ever rose to the surface. Constantine’s clothes: so noir. I recognize that the horror genre was the one they riffed on most explicitly in the American Gothic section, but the atmosphere, almost entirely coming from the art, really didn’t feel like a Friday the 13th movie or even horror from the 50s/60s like The Blob.

Chris: I think that effect – so much genre there’s a lack of genre – is Moore’s big contribution. American Gothic was probably a self-conscious attempt to “redeem” horror tropes, and I think it generally reads like a creative writing assignment (except for the zombie bits that I really love and we can talk about later…) Before that, I think the horror was more interesting, more organic, more free floating… it could seep into the story as needed.

Caroline: Exactly; it’s organic in form and content – which I really dug because it was so thematic.

Chris: Yeah, me too. I think that was on purpose: fecundity as motif…

Caroline: No doubt. I loved the way the idea of organicism was this overarching conceit for the first part, in the imagery, in the storyline, and then also in the way the different story elements were integrated together. In many ways it’s a very non-linear tale – at least, for mainstream genre.

Chris: Sure. And, you know, why shouldn’t a Swamp Creature comic demonstrate a high level of craft?

Caroline: This makes me think of Noah’s comment from early on, and I think Suat’s too, that they’re “massively massively overwritten.” That sort of implies a lack of craft, doesn’t it?

Chris: I suppose so…

Caroline: I guess, like I was saying at the beginning, I didn’t carefully read and commit to memory every textbox, so I’m sure there were particularly purple passages that I completely skimmed over. But I don’t think I’ve ever read a true work of genre fiction with that careful close reading. I’m not sure what the payoff of spending my time that way would be. I read Zizek that way, but not Heinlein.

Chris: There were passages and lines here and there that made me cringe… but overall, I thought he had a good batting average.

Caroline: Flipping back through it and looking at people’s examples, there are definitely purple passages, but they just didn’t bug me because I wasn’t reading at that grain. I was trying to hold on only as tightly as it took to stay on the ride.

Most just didn’t strike me as overwritten, although the example Noah comes up with really is pretty egregious:

“the interminable, tortuous extended metaphor comparing the emergency care ward of a hospital to a forest is probably the absolute low point of this volume— “in casualty reception, poppies grow upon gauze, first blooms of a catastrophic spring…a chloroform-scented breeze moves through the formaldehyde trees…”

What do you think, can we defend that on the “fecundity as motif” grounds?

Chris: I would say yes.

Caroline: OK. But it probably works because of the tightness of that fecundity/organicism metaphor. I’d say the whole thing may be a little overgrown, but that’s kind of the point…

Chris: I’ll offer an example of a kind of overwriting that I think would irritate you: Hellblazer, the John Constantine spin-off. I haven’t re-read it in a long time, but it also used a very florid prose style. But to me, it seemed more like a coat of paint slathered over the story.

Caroline: That’s a good way to describe what I felt about this one. There was definitely purple prose in places, but it was like a bad paint job, not a rotten board.

Chris: I don’t think that’s quite what I mean. With Jamie Delano, who wrote Hellblazer, the purple stuff is all on the surface, it really detracts from the overall effect. Even when Moore’s at his most purple, I don’t think you’re intended to take the overwriting seriously: it all just seems very playful. Delano was (in my hazy memory) utterly humorless, and that made his writing really insufferable to me.

Caroline: I see where you’re going – with Delano, there’s an earnestness to the purple prose that makes you sort of laugh at him. With Moore, it’s like a Magic Kingdom ride through genre fiction with a somewhat outlandish character on the loudspeaker. Set in a swamp.

Chris: Talk about purple prose.

Caroline: I try.

Chris: But yeah, Delano struck me as “earnest angry young man in coffeehouse.” (I don’t want to rag on him totally. Hellblazer did have some good long term character development in it, but man, was it a slog to get through…) But Moore is very freewheeling, libertine. A little like Sam Delany.

Caroline: I’ve been on this Delany kick lately.

Chris: Yes, I know.

Caroline: Pfft.

Chris: It reminds me of that sequence I keep pointing out in Motion of Light in Water. I should maybe pull the quote, but basically, Delany talks about the ‘60s, and how the era crystallized for him as he listened to a Motown song: The song – with all the typically slick Motown production – was just full of callouts and references to all kinds of other things in music and in culture; it was kind of a smorgasbord of stuff from the larger world just distilled into 3 minutes of pleasureable pop. And Delany noticed from there that that was happening all over the place at the time. “Nothing was forbidden,” so to speak. It informed his writing and his life.

Caroline: Right, Moore is working with what is really not a single genre, but ALL the major pop genres in aggregate. But do you think he’s imposing this ‘60s sensibility onto the book?

Chris: I don’t know if it’s specifically ‘60s; Delany perceived it as ‘60s. I don’t know that Moore necessarily did/does. But a similar sensibility, yes.

Caroline: The yams are pretty psychedelic – and the yam sex sequence is very psychedelic, visually and conceptually. But the book is, of course, from the 1980s. I guess I think that in some ways, there’s a “visual history as trope” in the book. The colors are very ‘70s; the horror images do have a little bit of a ‘50s feel to them, the teenagers in the car especially; the ‘60s psychedelia. The scene in #20 with the gunmen standing around the shot-up Swamp Thing looks a little like 1940s-era military images. There’s nothing I’d really identify as ‘80s but it was early in the decade…

Chris: Well, Constantine is Sting…

Caroline: There ya go.

Chris: There were punk vampires and some side characters, too. The spirit is hippie-era, but I guess it’s a bit punk-era too. That sort of “try anything” ethos…

Caroline: The hippie feel definitely dominates the punk feel to me. The art doesn’t feel punk.

Chris: You don’t think so? Well, I guess not like Gary Panter or anything like that.

Caroline: This is some seriously skilled art. Bissette is not the Sid Vicious of cartooning.

Chris: True.

Caroline: Constantine is really Sting?

Chris: Supposedly. Bissette was a fan and just liked drawing him. It fell by the wayside by the time he got his own book.

Caroline: So he wasn’t doing anything with the fact that it was Sting. Sting was just the model for the physical character.

Chris: Yeah. I’ve always loved the way Constantine sort of knows everybody, from bikers to nuns to boho NYC artists to geeks to friggin’ Mento from Teen Titans. The way he sort of flits from world to world is very much in that Moore-Delany cosmopolitan spirit.

Caroline: Right. “Libertine” applies to Constantine in a slightly more conventional sense. But it’s all held together by this notion of being unrestrained. I suppose that’s ironic, but it’s a very playful irony. Worlds in this comic are very permeable, boundaries are very fluid and overlapping. Nothing’s discrete.

Chris: Characters, history, geography, genre. I’m impressed by Moore’s willingness to play genre mash-up. The most significant example of this is horror + heroics. I confess I’m not a horror guy, so I’ll cheerfully be corrected by someone who knows better, but it strikes me that horror protagonists tend to be victims, passive characters. Moore’s reimagining of Swamp Thing, post-Anatomy Lesson, casts him as an active hero. While the JLA commiserate up in their satellite HQ on how useless they are against Woodrue, who is down on earth (get it?) plowing through the muck (get it?) getting things done? Moore’s Swamp Thing is active, but he’s not the bad guy. He’s defined as a hero and an individual: “This is what I can do. This is how I am unique and where I can make a difference.” Or to use a direct quote: “I am in my place of power… and you should not have come here.” I must confess, I hadn’t reread these for some time, and while I vaguely remembered that Swampy-Arcane battle that included that line, I’d forgotten just what a can of whup-ass Swamp Thing unloaded there. It was awesome, and I mean that seriously. It’s heroics and horror… shouldn’t awe be a basic ingredient? I think it should, but, say, in a typical Justice League comic – it’s just not there. Moore gets it. He remembers to put it in.

Caroline: So this sense that things are libertine and unrestrained works from the perspective of someone coming into the book from the comics tradition as well as for someone like me, coming in via more general genre fiction. The expectations of people familiar with comics are equally muddied up.

Chris: Absolutely. You know, I think the perfect illustration of Moore’s take on genre appears in the Voodoo/Zombie 2-parter. I think some of the most perfect moments in Moore’s run are in that episode. The zombie bits really sing (for me, at least), and I really love the little moments that play against genre expectation in touching and logical ways.

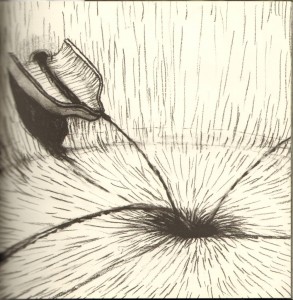

Caroline: I was particularly keen on the first page of that, where he’s detailing the claustrophobia and tedium of “life” in the grave.

Chris: Yeah, you can argue that it’s Moore showing off his prose for its own sake…

Caroline: Wait, you really think it’s particularly prosaic? I didn’t really get that.

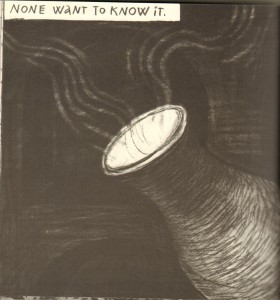

Chris: Well, it’s mostly prose. The pictures are just there for the punch line, when he rolls over onto his side: “He couldn’t sleep.”

Caroline: True.

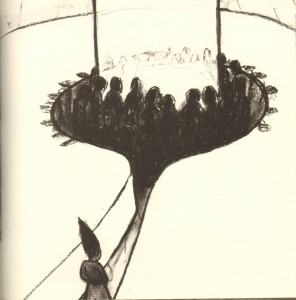

Chris: But I think this imagining of the zombie POV pays off nicely down the road. When the dead father appears before his (now) middle aged daughter, we don’t get the standard “I will eat your brain” sequence, just a father-daughter reunion that is genuinely touching.

Caroline: Yeah, “touching” usually isn’t an emotion that shows up in zombie stories.

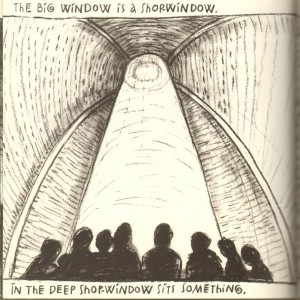

Chris: And when the walking dead is still walking by the end of the book and has to get a job, our hero gravitates back toward enclosure, and takes tickets at the local movie house (where the horror movie posters all look absurd in comparison). Come on! That’s funny!

Caroline: It’s that unrestrained permeability again. The undead are usually pretty non-human, but he humanizes them to great comic and emotional effect.

Chris: That’s what works for me: Moore inhabits the horror. He imagines himself as the zombie. The pathos is earned, the emotion is real, the absurdity wittily acknowledged. It’s drama and humor both. Straight-up horror would have bored me. It kind of did, in much of the rest of Gothic. (And generally, only during Gothic, and its plastic conception; not so much pre-Gothic). But Moore’s zombie arc is a sort of mini-masterpiece of sympathetic writing and willingness to dance outside the grave. It’s very polymorphously perverse…

Caroline: That’s such a great phrase. The polymorphism is a huge theme in this book and it’s present at every single level. That’s extremely satisfying to me, even from the “art reading” perspective.

There’s a couple of ways to think about it, I guess: you can think of mainstream comics as their own subgenre of genre fiction, like science fiction or romance or horror, with their own tradition and their own tropes. Or you can think of them as expressions of the same genres that you have in fiction, so that science fiction comics and science fiction novels and science fiction short stories are all instances of science fiction. I think Moore definitely went for the latter approach in this book, although he apparently also paid attention to the comic book tradition and tropes.

So the book is polymorphic in relation to these two ways of situating itself – I gotta say that even though I don’t think Moore was really showing off his smarts here, it really is smart how even at that very topmost almost meta-writerly level, he’s still consistent with his surface-level content and themes.

Chris: Moore recognizes that it’s all story: horror into superheroes into romance into comedy into “mainstream fiction.” He respects them all and, at his best, promiscuously blends them into one another with a true libertine spirit. The Swamp Thing–Abby romance is appropriate: breaking taboos and cross-kingdom pollenization – because why not?