In 2007, Jonathan Lethem published an extended essay in Harper’s on the nature of creative inspiration and the ways in which all creativity draws on a cultural wellspring of ideas and representations. Called “The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism” it contains the following passage describing the “open source” culture behind the origins of the Muddy Waters song “Country Blues”:

“I made it on about the eighth of October ’38,” Waters said, “It was fixin’ a puncture on a car. I had been mistreated by a girl. I just felt blue, and the song fell into my mind and it come to me just like that and I started singing.” Then Lomax, who knew of the Robert Johnson recording called “Walkin’ Blues,” asked Waters if there were any other songs that used the same tune. “There’s been some blues played like that,” Waters replied. “This song comes from the cotton field and a boy once put a record out – Robert Johnson. He put it out as named “Walkin’ Blues. I heard the tune before I heard it on the record. I learned it from Son House.” In nearly one breath, Waters offers five accounts [of the song’s authorship]…

Lethem’s essay is, as the title suggests, entirely composed of plagiarized fragments of text, knitted together into a new whole. Whether due to his fame, to Harper’s influence as a literary publication, or to some resistance to commodification inherent to natural language, nobody objected too vociferously to the use of his or her words, although Lethem’s strategy did prompt some commentary (all of which is behind subscription locks.)

Around the same time that Lethem’s article was hitting the newsstands, cartoonist Nina Paley was hitting a brick wall in the production and distribution of her blues-inflected animated full-length feature film, Sita Sings the Blues. Made by Paley single-handedly in her Manhattan apartment, Sita brings together an embarrassment of source-material richness: Paley’s own humor-filled story of breakup-by-email, the ancient Indian epic Ramayana, and the blues songs of ‘20s American songstress Annette Hanshaw.

Despite the “open source” culture of indigenous blues, it’s those Hanshaw recordings that led her to the brick wall: the recordings’ are restricted by copyrights held by large corporations like Sony and EMI. The cost of licensing the music used in Sita would have cost her more than it cost to make the entire film. She explains the copyright obstacles facing the film and its soundtrack on her blog.

Paley’s imaginative solution to the problem has been to give the film away for free, and the result has been a firestorm of enthusiasm for all things Sita. Paley says that her new “free culture” lifestyle has eradicated her cynicism and made her even more creative than before. A lot of that creativity at the moment is going into promoting the idea of free culture: her Facebook page boasts a charming jingle and accompanying animation clip promoting the idea that “copying isn’t theft”:

(The “draft needs your audio” refers to Paley’s request that musicians make their own versions of the ditty she sings in this vid.)

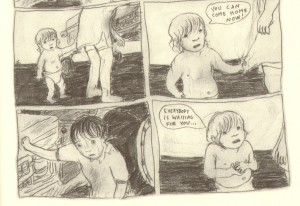

You can watch Sita online (click through rather than watching the embedding ’cause the right side is cut off):

or download it from its homepage.

Lethem explains in his essay that the surrealists felt our experience of life is “dulled by everyday use and utility,” and understood cinema and photography as art forms that “reanimate the dormant intensity” of the “matter that made up the world.” Paley’s animated film accomplishes a similar “reanimation”, but it’s not corporeal material that’s made more relevant and compelling through her representation, it’s the “primal stories” of the source material. In her own words:

Sita’s story has been told a million times, not just in India, not just through the Ramayana, but also through American blues. Hers is a story so primal, so basic to human experience, it has been told by people who never heard of the Ramayana. The Hanshaw songs deal with exactly the same themes as the epic, but they emerged completely independent of it. Their sound is distinctly ‘20s American, and therein lies their power: the listener/viewer knows I didn’t make them up. They are authentic. They are historical evidence supporting the film’s central point: the story of the Ramayana transcends time, place, and culture.

Lethem probably wouldn’t use the language of timelessness to describe this effect – his essay observes that “serious fiction” is “liberally strewn with innately topical, commercial, and timebound references,” pretty much like everything else. But Paley’s point is really more about primacy than timelessness – things common to human experience, things not transcendent to culture but merely so common among cultures that they seem universal.

But it’s not just that juxtaposition of those common elements from several cultures that animates Sita: it’s also the mark of the artist’s hand. At the risk of tautology, the animator re-animates. But not just in the literal sense: for culture to remain alive and to become mature, to learn from accumulated experience and insight, artists have to be able to take it into their hands and renew, revitalize, and re-animate it. The more locked down it is behind copyright, the harder it is for artists to do that, and the less alive the culture is.

Listen to Paley talk about free culture to the non-profit Public Knowledge:

Or if you’re interested in the business model, here’s her presentation to the National Film Board of Canada: