Let’s hear it for menstrual blood.

Radioactive spiders, super-soldier serums, shouts of “Shazam!”, they’re all second best attempts to transform puberty into the fantastical. But puberty already is fantastical. Blood spilling from your genitalia? No warning, no spider-senses tingling, just a biological transformation as instantaneous as a gamma bomb.

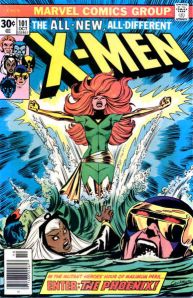

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby hinted at it first, when a teenage Jean Grey’s taxi pulled in front of the Xavier School for Gifted Youngster back in 1963. Later writers replaced Miss Grey’s mutant menstruation with a telekinesis-spilling car accident when she was ten (an increasingly common age for menarche, though the average is still twelve). When a teenage Rogue arrives at the School in 2000, the grown-up Dr. Grey tries to spell it out for her: “These mutations manifest at puberty and are often triggered by periods of heightened emotional stress.”

Yep, you heard right: “triggered by periods.” Even X-Men director Bryan Singer buries the horror of menstruation in the middle of the sentence. That’s why we need Stephen King. It takes a horror writer to spill the blood.

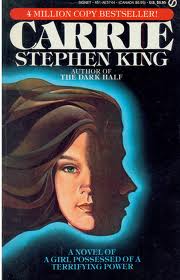

Like Jean Grey, Carrie White is a telekinetic mutant who discovers her powers at puberty. But King doesn’t beat around the proverbial bush. He puts us in the girls locker room when Carrie menstruates for the first time and bullies pelt her with tampons. “The period,” explained King in an interview, “would release the right hormones and she would rain down destruction on them.”

King’s Ewen High School in Chamberlain, Maine is far far away from Professor X’s “exclusive private school in New York’s Westchester country.” Stan and Jack’s mostly male, mostly pre-pubescent readers weren’t ready for a Jean Gray tampon scene. In 1974, when Carrie was first published, The X-Men were in reprints.

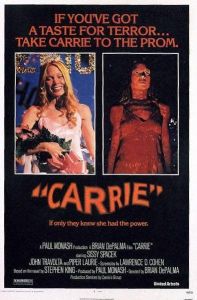

I doubt King was aware that his main character was a knock-off of Marvel’s second Silver Age superheroine. He was just trying to prove to himself that he wasn’t “scared of women” (someone had accused him of writing only about “macho things”). He typed the menstruation scene and then tossed it in his wastebasket. “I hated it,” he said. It took his wife to fish out those first three pages and bully him into writing a couple hundred more. Next thing Sissy Spacek is getting herself nominated for Best Actress.

The Brian De Palma film was still in production when Chris Claremont relaunched the X-Men in 1975. When Carrie White leapt from paper to screen the following year, Jean Grey was transforming from Marvel Girl to Phoenix. Kirby penned Jean cowering on the cover of X-Men No. 1. Lee admitted that he sometimes forgot what her powers were (he misidentifies telekinesis as “teleportation” in that first issue). But Dave Cockrum’s Phoenix explodes across X-Men No. 101, and soon Claremont makes her the most powerful mutant on earth, dwarfing even Professor X.

By 1980, Dark Phoenix is swallowing stars like air. Which says a lot about the circularity of cultural influence. It only took four years for the inspiration for Carrie to become Carrie. King’s mutant murders everyone at her prom and razes most of her hometown. Jean Grey takes out the population of an entire planet, but the result is the same: both pregnancy-ready women have to die.

Carries bleeds out from a mother-inflicted knife wound, while Jean superheroically commits suicide. Carrie’s hyper-religious mother stabs her because Mrs. White considers her own daughter an abomination against God. Which is true of Miss Grey too. Mutants are the engine turning Darwin’s God-usurping evolution. Mutations that increase the likelihood of reproduction are Naturally Selected. You might think telekinesis would be pretty damn adaptive, but it’s top two female specimens died before they reproduced. Otherwise menarche would be accompanied by more than just internal explosions.

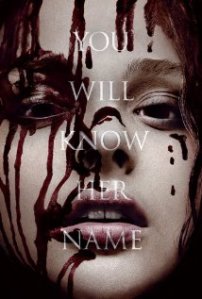

Of course Jean and Carrie don’t stay dead for long. I’ve lost track of the number of times Jean has returned and/or been cloned. Stephen King never wrote a sequel, but his first-born mutant was resurrected for a film sequel, a stage musical, and a made-for-TV remake designed to launch a series. All were flops. So you have to admire Boys Don’t Cry director Kimberly Peirce for wading anew into all that pig and menstrual blood. She’s not scared of women either.

Carrie wasn’t her first choice for next project (the producer came to her), but when Peirce reread the novel, she realized: “Oh, these are all my issues: I deal with misfits, with what power does to people, with humiliation and anger and violence. Carrie has gone through life getting beaten up by everyone. She’s got no safe place. And then she finds telekinesis — her talent, her skill — and it becomes her refuge. And I thought, Wow, this is an opportunity to make a superhero-origin story. With her period comes the power. With adolescence comes sexuality, and with sexuality comes power.”

In other words, the best thing about Peirce’s Carrie are the vaginas. Not that we ever see one. She opens with Carrie’s home birth (the amniotic-soaked Bible on the stairs is a nice touch), but Julianne Moore’s dress hem hides everything else. I ducked my head behind the surgical screen during my wife’s c-section, but I can report that the table rocked with the doctor’s sawing and the floor required a mop afterwards. But horror movie horror is about controlling horror (usually by exaggeration) and so paradoxically lessening its effect. Peirce at least knows where the horror crawls out from.

Soon Kick-Ass actress Chloë Grace Moretz’s vagina threatens an appearance during the shower scene (with a brilliant nod to Hitchcock), and the first objects she moves with her mind are all those tampons. Then the whole movie is drenched in half-births. Carrie’s water breaks when she explodes a drinking cooler in the office of a principal scared to say the word “period.” When Carrie’s mother locks her in a womb of a closet, Carrie cracks a slit down the length of the door; an hour later Mom is midwifing herself through the bloody opening. Carrie cracks a larger slit under the car of the bully who turned her into Red Phoenix. The girl dies half-born, her crowning face caught in the vagina dentata of the bloody windshield. Carrie, like her sister Jean, finally ends her own life–though the crack in the tombstone keeps at least the vagina motif alive.

Ultimately, the new Carrie doesn’t add much to either De Palma’s or King’s, both of which at least spoke to their times (read Gloria Steinem’s Ms. essay “If Men Could Menstruate” if you’re in doubt). But the real horrors remain too much in the visual subtext (and that includes the Columbine shootings). Why not employ all the powers of CGI to show infant Carrie struggling out of the birth canal? Why not show the harrowing, bathroom stall moment when Carrie inserts her first tampon?

Metaphors are nice and all, but Carrie remains too marooned in the 70s. Or maybe our culture hasn’t really grown in those forty years. We’re still the same horrified middle schoolers cringing through Sex Ed class. We’re still scared of women.