So I’ve been reading Charles Soule and Javier Pulido’s new She-Hulk title, and really enjoying it. But it got me thinking about comics and genre a bit, and puzzling over the question that makes up the title of this post: Is this comic a superhero/superheroine comic? I think it isn’t (and, further, that is a good thing!)

So I’ve been reading Charles Soule and Javier Pulido’s new She-Hulk title, and really enjoying it. But it got me thinking about comics and genre a bit, and puzzling over the question that makes up the title of this post: Is this comic a superhero/superheroine comic? I think it isn’t (and, further, that is a good thing!)

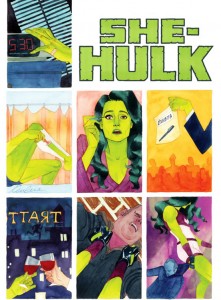

Some background: The new She-Hulk series focuses on Jennifer Walters/She-Hulk’s legal career. Of course, some superheroing does occur (it has to – the She-Hulk is an Avenger, after all!). But even when it does, it is in service to aspects of the plot directly tied to the She-Hulk lawyering activities (for example, she is attacked by automated robots when attempting to contact Tony Stark regarding a case) or social activities (at the end of a night out, Patsy Walker/Hellcat convinces the She-Hulk to cheer her up by helping her raid a Hydra facility). In short, the comic is about a superheroine. But it doesn’t seem to be about the fact that she is a superheroine.

Now, the term superhero comic is a genre term – it refers to a type of comic that contrasts with war comics, romance comics, crime comics, funny animal comics, etc. Although I don’t want to tie discussion to any single theoretical account of genre, it seems clear that particular works of art get grouped together into a single genre based on having certain, aesthetically and narratively relevant, characteristics in common – these might include setting, theme, plot, style, etc. Further, once a genre exists, other works (both within and outside the genre) can be fairly interpreted not only in terms of their inherent characteristics, but also in terms of how those characteristics relate to the characteristics standardly associated with the genre in question. As a result, not every comic with a superhero or superheroine in it is necessarily a superhero comic in the relevant sense (just as not every story with a cowboy in it is a western). And given this understanding, the new She-Hulk series just doesn’t seem to be a superhero comic: it lacks too many of the standard characteristics associated with the genre (even the John Byrne and Dan Slott runs with the character, for all their metafictional weirdness and their development of the working lawyer side of the character, still revolved primarily around the standard sort of hero-versus-villain superhero plot). Of course, given the presence of a superheroine as protagonist, proper interpretation of the comic will likely benefit from comparison, and contrast, with more run-of-the-mill superhero comics, but that doesn’t mean that it is one.

Now, the term superhero comic is a genre term – it refers to a type of comic that contrasts with war comics, romance comics, crime comics, funny animal comics, etc. Although I don’t want to tie discussion to any single theoretical account of genre, it seems clear that particular works of art get grouped together into a single genre based on having certain, aesthetically and narratively relevant, characteristics in common – these might include setting, theme, plot, style, etc. Further, once a genre exists, other works (both within and outside the genre) can be fairly interpreted not only in terms of their inherent characteristics, but also in terms of how those characteristics relate to the characteristics standardly associated with the genre in question. As a result, not every comic with a superhero or superheroine in it is necessarily a superhero comic in the relevant sense (just as not every story with a cowboy in it is a western). And given this understanding, the new She-Hulk series just doesn’t seem to be a superhero comic: it lacks too many of the standard characteristics associated with the genre (even the John Byrne and Dan Slott runs with the character, for all their metafictional weirdness and their development of the working lawyer side of the character, still revolved primarily around the standard sort of hero-versus-villain superhero plot). Of course, given the presence of a superheroine as protagonist, proper interpretation of the comic will likely benefit from comparison, and contrast, with more run-of-the-mill superhero comics, but that doesn’t mean that it is one.

All of this points to a rather illuminating observation regarding the comics industry. Until the rise of a number of upstarts in recent years, DC and Marvel jointly had a near-monopoly on recognizable superheroes (and between the two of them still own the majority of this particular narrative resource). As a result, however, they seem to have concluded that, since they had a lot of superheroes in their stable, they should only make superhero comics. It is not only that they don’t publish very many comics that don’t feature superheroes. In addition, for the most part they have failed to publish any comics that feature superheroes/ heroines in anything but the generically-bound sort of stories we are used to seeing superheroes/ heroines appear in. This might not seem all that weird or short-sighted at first glance, but imagine a similar (imaginary) scenario in film: MGM signs Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood, James Garner, and John Wayne to exclusive, long-term deals, and then decides that it had better make westerns, and only westerns, from then on.

All of this points to a rather illuminating observation regarding the comics industry. Until the rise of a number of upstarts in recent years, DC and Marvel jointly had a near-monopoly on recognizable superheroes (and between the two of them still own the majority of this particular narrative resource). As a result, however, they seem to have concluded that, since they had a lot of superheroes in their stable, they should only make superhero comics. It is not only that they don’t publish very many comics that don’t feature superheroes. In addition, for the most part they have failed to publish any comics that feature superheroes/ heroines in anything but the generically-bound sort of stories we are used to seeing superheroes/ heroines appear in. This might not seem all that weird or short-sighted at first glance, but imagine a similar (imaginary) scenario in film: MGM signs Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood, James Garner, and John Wayne to exclusive, long-term deals, and then decides that it had better make westerns, and only westerns, from then on.

As a result, the new She-Hulk series is notable for two reasons. The first is that it is, if the first two issues are any indication, one of the coolest comics being published today (of course, people that know me know it is likely that I would say that about anything with Shulkie in it, so take with a liberal dose of salt if necessary). More importantly in the long run, perhaps, is that the new She-Hulk might signal Marvel’s willingness to explore different sorts of stories, and different sorts of genres, with their characters. If we are lucky, then maybe we will get all sorts of new stories, utilizing new perspectives, that explore all sorts of aspects of our favorite superheroes, superheroines, supervillains, and supervillainesses, and not just their ability to beat each other up or get all angsty about how hard it is to beat each other up. While battling-super-people stories are great (it is what got me into these comics in the first place), stretching a bit in this manner would be welcome too.

But maybe I am wrong, and the difference between this comic and previous mainstream superhero stories isn’t as vast as I think. So, is the She-Hulk a superhero comic?