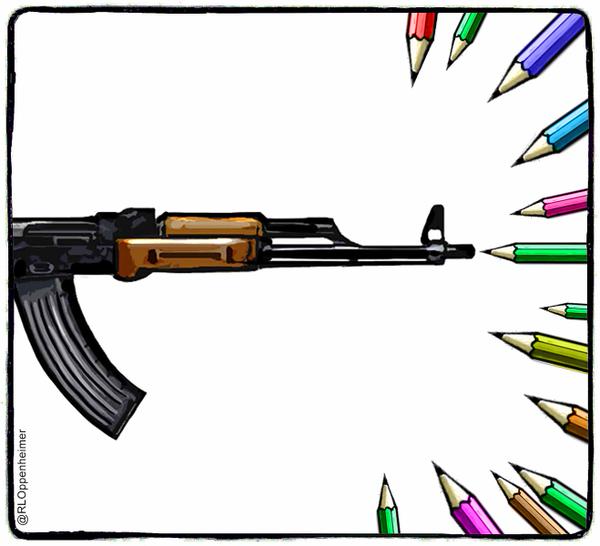

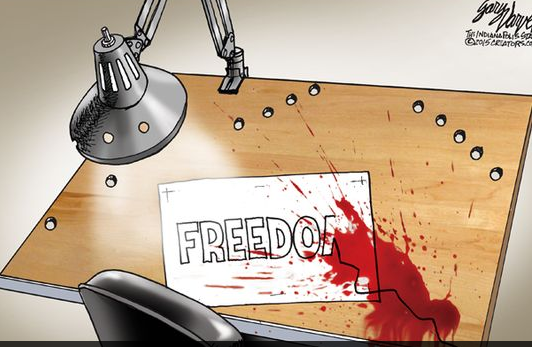

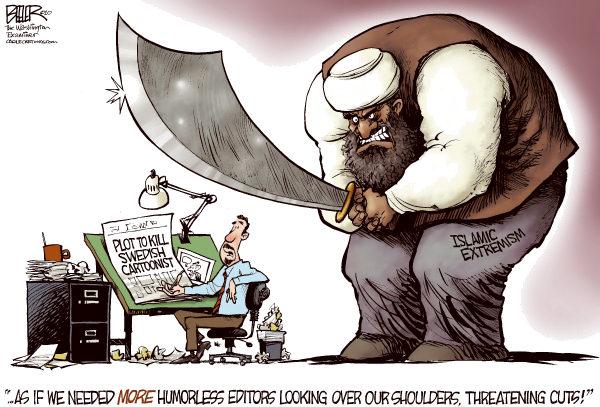

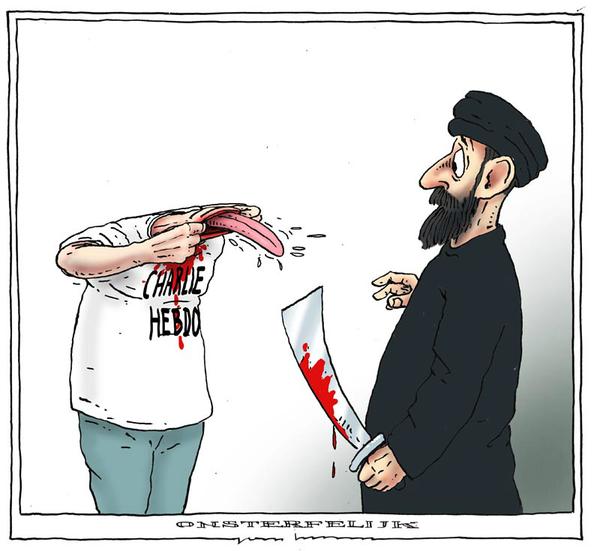

In the wake of the tragedies that have occurred in Paris over the last few days a number of commentators, some traditionally left-leaning and some more obviously right-wing, have suggested that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo contributed to the climate of extremism that led to these attacks. The arguments often take the form of a double assertion: first, that the cartoons in question were flagrant or “unnecessary” violations of the Muslim prohibition against images of the Prophet; and second, that these violations were motivated by Islamophobia and racism. The conclusion, merely implicit in some commentaries and more explicit in others, is that because the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo were also racist bullies they bear a degree of culpability for what happened; consequently, they also make poor martyrs for either the profession of satirical cartooning or the right to free speech.

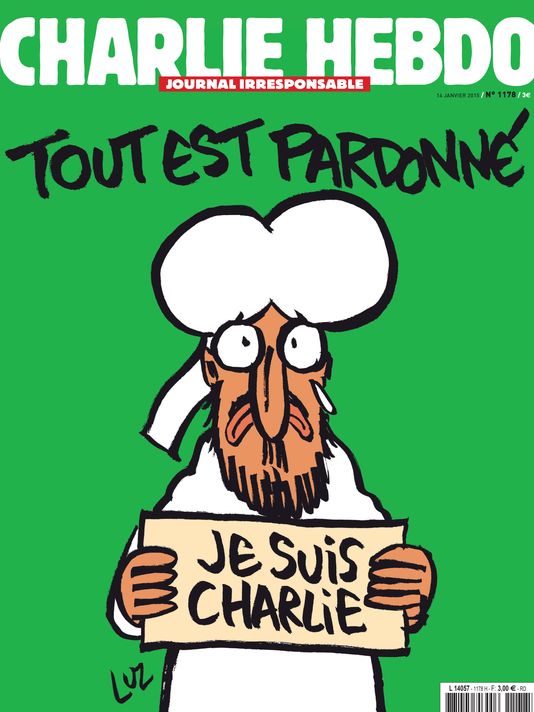

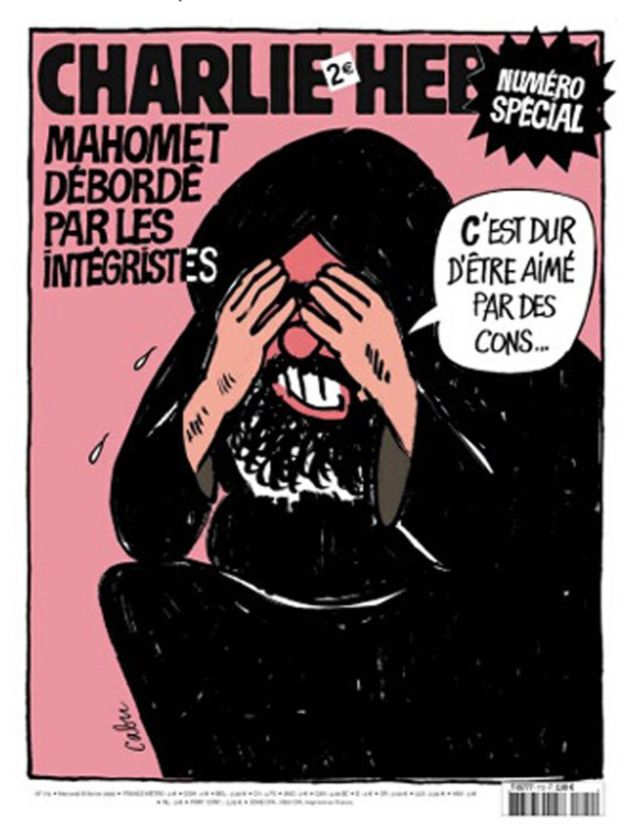

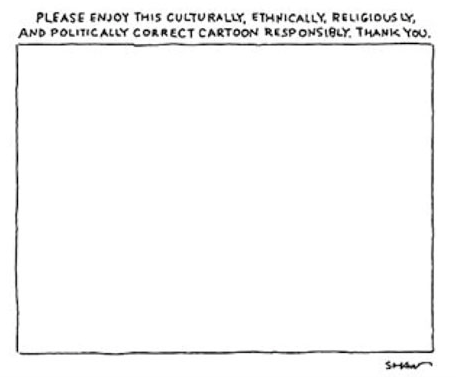

The cover of this week’s edition of Charlie Hebdo.

There are several problems with this argument, however. Most troublingly, to imply that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo contributed to the radicalization of Muslims by repeatedly violating an important tenet of Islam reduces the wide range of Muslim opinions on this specific issue to the extreme position held by the terrorists themselves. To take up this position is to fail to understand that the so-called “prohibition against images of the prophet” is actually already a radical interpretation of Islamic doctrine. No such prohibition exists in The Qu’ran. In fact, significant numbers of Muslims do not hold to this supposed prohibition, and even among those who do, interpretations of the precise meaning and purpose of the relevant phrases in the hadith literature are diverse. (On this topic, see here.

But there are other reasons for resisting the argument that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo were somehow responsible for creating the climate of extremism that led to this incident. The more I learn about the work at Charlie Hebdo (and I admit I have more research to do in this regard), the more I am convinced that this implication is unjust and unfair.

I am a British-born academic who has lived in the United States for over two decades; I am largely ignorant of contemporary French culture, and I confess I am only now becoming even superficially familiar with Charlie Hebdo (just like most of us, I suspect). But from what I have been able to ascertain in my preliminary investigations, while the cartoonists at the magazine were commenting satirically upon religious extremism, they were not creating it. The extremism was already there. They were calling it out — perhaps in a foolhardy way, perhaps courageously, and with varying degrees of mean and clever wit — but they were reacting to something that was already present in the culture, and that was being fostered by even more negative, reactionary, and ill-intentioned forces based outside France. (Indeed, no matter what one thinks of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, any role they could have played in radicalizing these particular terrorists is surely outweighed by Said Kouachi’s months of training in Yemen under a branch of Al Qaeda.)

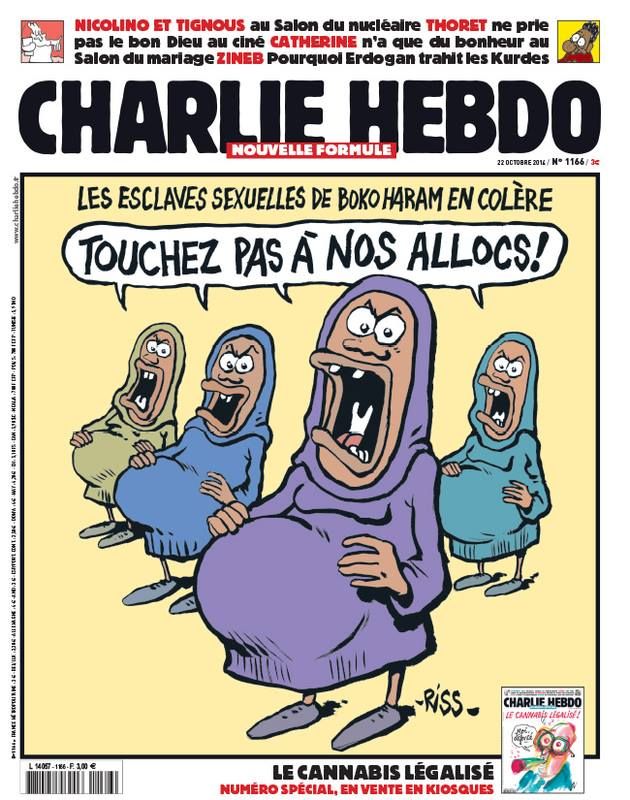

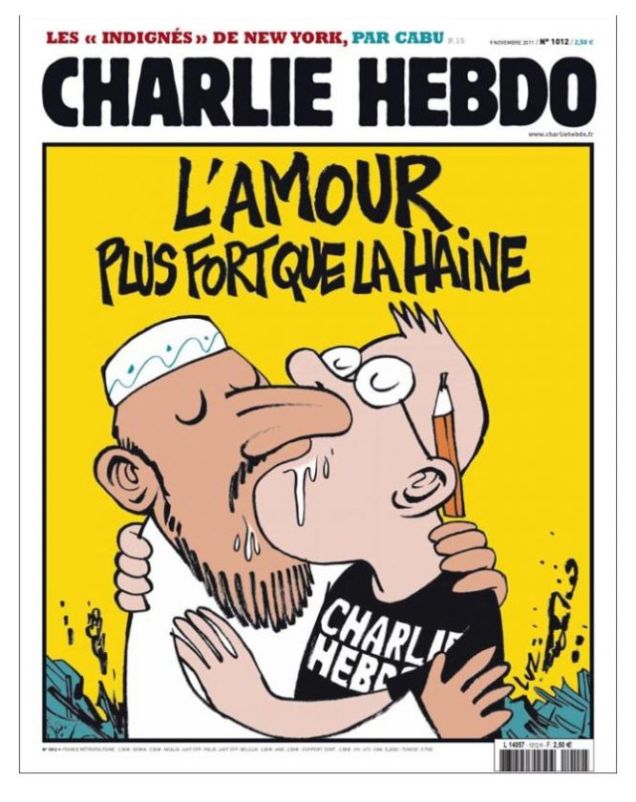

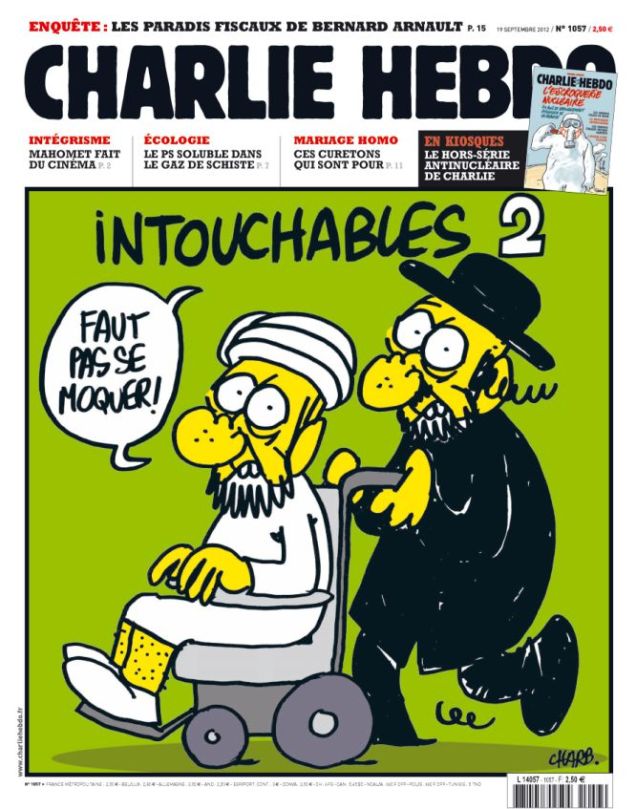

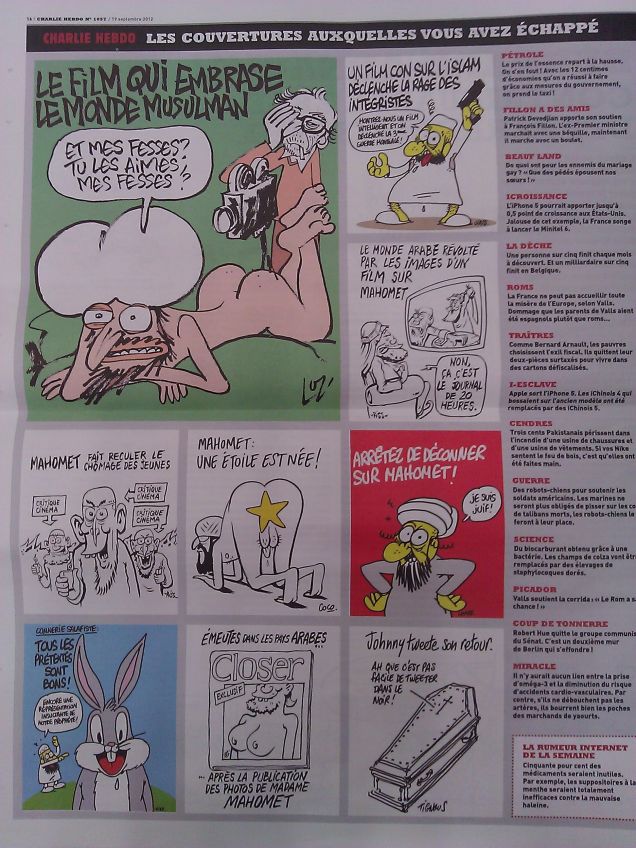

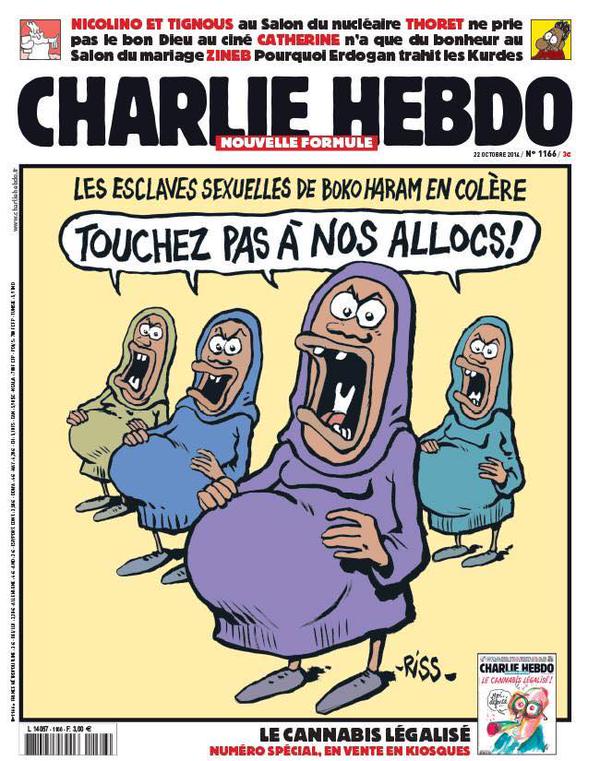

Nor does it seem correct to accuse the editors at Charlie Hebdo of racism, as some have done. Experts who are better informed than me with regard to the history and culture of French comics (the brilliant Bart Beaty, for example) tell me that, on the contrary, the editorial position of the magazine was consistently anti-racist. This is not to say that a case against individual cartoons could never be made; caricature is an art-form built on principles of exaggeration and abstraction, and the point at which the visual “shorthand” of the cartoonist becomes a stereotyping technique cannot be fixed, but will vary from situation to situation and viewer to viewer. Nevertheless, any such case would have to be made within the larger anti-racist intentional context of the magazine, and nuanced accordingly. I’ve yet to read such context-sensitive work; it is not a feature of those denunciations of Hebdo as “racist” that I have seen. Nor does there appear to be any evidence that the editors at the magazine regarded the Muslim community in general with hostility. In fact, there appears to have been at least one person of Muslim heritage on the staff at Charlie Hebdo who was killed in the attacks: Mustapha Ourrad, a proofreader.

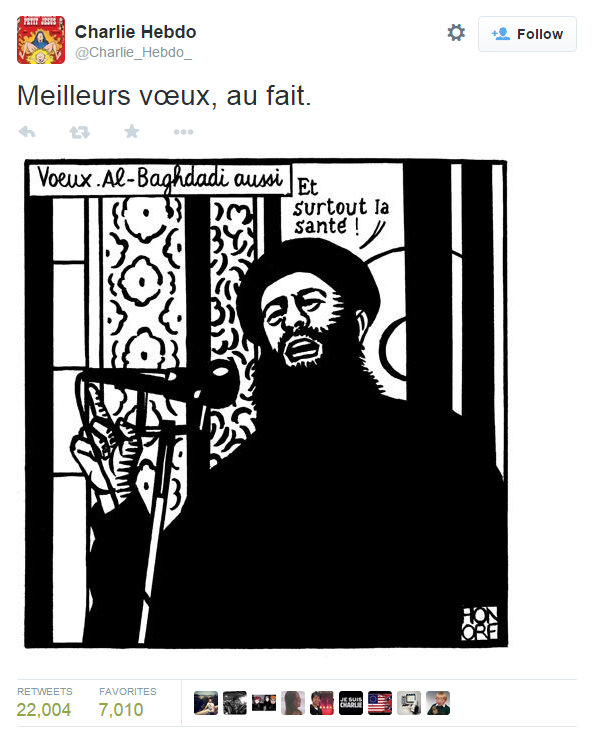

Yes, Charlie Hebdo published work that was profoundly hostile towards religious extremists within Islam; it was similarly hostile towards other religious authoritarians, too (which is probably why rightwing Catholics like Bill Donahue have been willing to suggest that the cartoonists were essentially asking for it). Indeed, the general stance of the magazine appears to have been one of gleeful contempt for religious and political hypocrites of all stripes. Certainly, the boost that explicitly racist politicos like Le Penn are currently seeing in the French polls in the wake of these events would have horrified Charlie Hebdo’s editor Stephane Charbonnier, a life-long left wing activist who was (according to the New York Times) raised in a family of French communists. In fact, I think Charb would be commissioning some bitterly ironic anti-fascist cartoons in the wake of the current xenophobic rightwing groundswell — if only he were here to do so.

In other words, the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo seem to have been exactly what you might expect satirical cartoonists in the French tradition to be: mockers of pomposity and demagoguery of all kinds.

I think I understand the motivations of at least some of the critics of Charlie Hebdo, even if I do not agree with their assessment of the magazine. They are concerned, rightly, that Muslims of good will should not be held responsible for these crimes or bullied into silence; and they are concerned, rightly, that ongoing incidences of the victimization of Muslims in France, Britain, America, Palestine, and elsewhere should not be overlooked or worse yet, justified, in the wake of this outrage. And they are right because at a time like this it is obviously very important that Muslim voices (in particular) are heard, in all their diversity. Indeed, it is absolutely necessary that Muslims of good will should be welcomed to the table, so that we can repudiate vile, greedy fools like Rupert Murdoch when they spew their poison and ignorance into the world.

But surely it must be possible to include Muslim perspectives on this kind of violence without accusing the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo of political insensitivity (a criticism that seems to misunderstand the very point and purpose of satire), let alone deliberate racism (a charge that thus far appears to me unjustified)? Instead, and perhaps more productively, we could chose to emphasize that a man of Muslim heritage worked and died alongside the cartoonists at the magazine; that another Muslim man, a police officer named Ahmed Merabet, died defending the cartoonists at the magazine; and that yet another Muslim man, Lassana Bathily, saved several hostages from another terrorist at a Kosher grocery the next day. If we keep reminding people that members of the Muslim community were victimized here, and others also acted heroically, that will go some way towards making the reactions of people like Murdoch seem absurd, and make productive dialogue between social groups more possible.

In sum, and while there is no doubt much more that could be said, I think the suggestion that the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo are in any significant way culpable for the climate of extremism that led to these tragic events is unfair not only to those cartoonists but also to the many members of the Muslim community who would never in a million years respond to a cartoon — however offensive they deemed it — with a bullet. It also just puts the cart before the horse. After all, if a right wing Christian were to shoot Andreas Serrano for making “Piss Christ” I would not repudiate blasphemous artists for unnecessarily provoking radical Christians; instead I would ask what forces were at work to make some Christians feel that murdering artist-provocateurs was a necessary and acceptable defense of their faith. I wouldn’t think the act was somehow the responsibility of Christians everywhere, but neither would I blame Serrano himself — for all that “Piss Christ” is more readily legible as a desecration of a religious icon than any of the cartoons at Charlie Hebdo I’ve seen. (And I am aware that Serrano himself declares the work to be devotional.)

I write these remarks in the hope that they will be interpreted not as an attack upon those with whom I disagree, but in what I hold to be a spirit of fairness both to the dead and to the living, of all faiths and of none.

_______

For all HU posts on Satire and Charlie Hebdo click here.