Jean Giraud aka. Moebius had been battling cancer for years, cheating death on several occasions before finally letting go on Saturday. His illness marked his creative production in the last decade of his life, leading to the cancellation of certain projects, including two Endless collaborations with Neil Gaiman, and the sad dissipation felt in others, most notably perhaps his last book (2010), in which he revived his classic, mute character Arzak as a talking stiff-headed nobody in particular.

But it is also a strong undercurrent in the late, exhilarating creative surge of his improvised sketchbook comics series Inside Moebius (2000–2008) and his elegiac return to his greatest creation, The Hermetic Garage, in 2008’s Chasseur déprime — works in which he captured for the first time in decades some of the same searching energy that characterized his creative peak in the seventies, delivering it with the urgency of a man with a short lease.

While in a sense youthful, these works are simultaneously very much songs of experience, with Chasseur déprime as resonant a reflection as any in comics on old age. Uncertain, even insecure, and borderline depressed, but also wise. Nothing is ever really over in Moebius and he did love the serial, so it is fitting that the story leaves things open, ending on the obligatory “fin de l’épisode.”

I have previously written at some length about the book and its relation to his 1970s masterpiece, so I will just add a few observations here, pertaining specifically to its character of artistic testament.

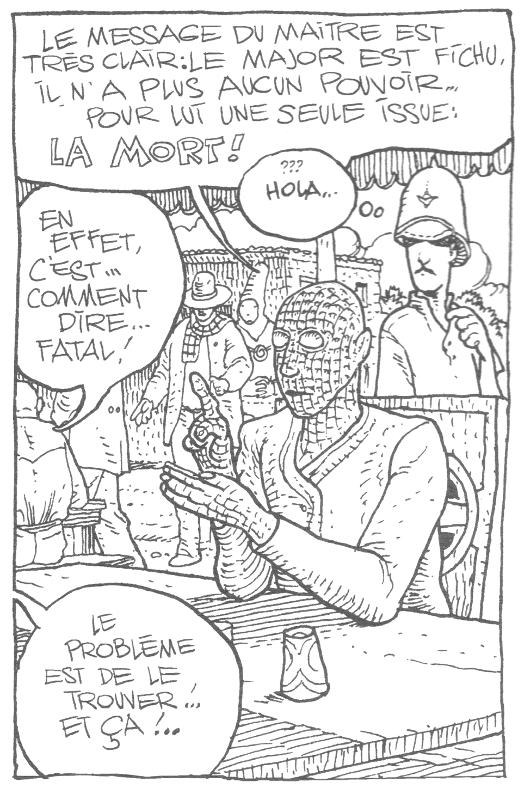

The plot — such that it is in this reiterative, oneiric work — concerns the protagonist, and Moebius’ alter-ego, Major Grubert, the demiurge-like creator of the tripartite world of the Garage, taking out a contract on himself, offered by one of his own creations. From the first pages of the book, we learn that there is only one possible ending for him: death.

The plot — such that it is in this reiterative, oneiric work — concerns the protagonist, and Moebius’ alter-ego, Major Grubert, the demiurge-like creator of the tripartite world of the Garage, taking out a contract on himself, offered by one of his own creations. From the first pages of the book, we learn that there is only one possible ending for him: death.

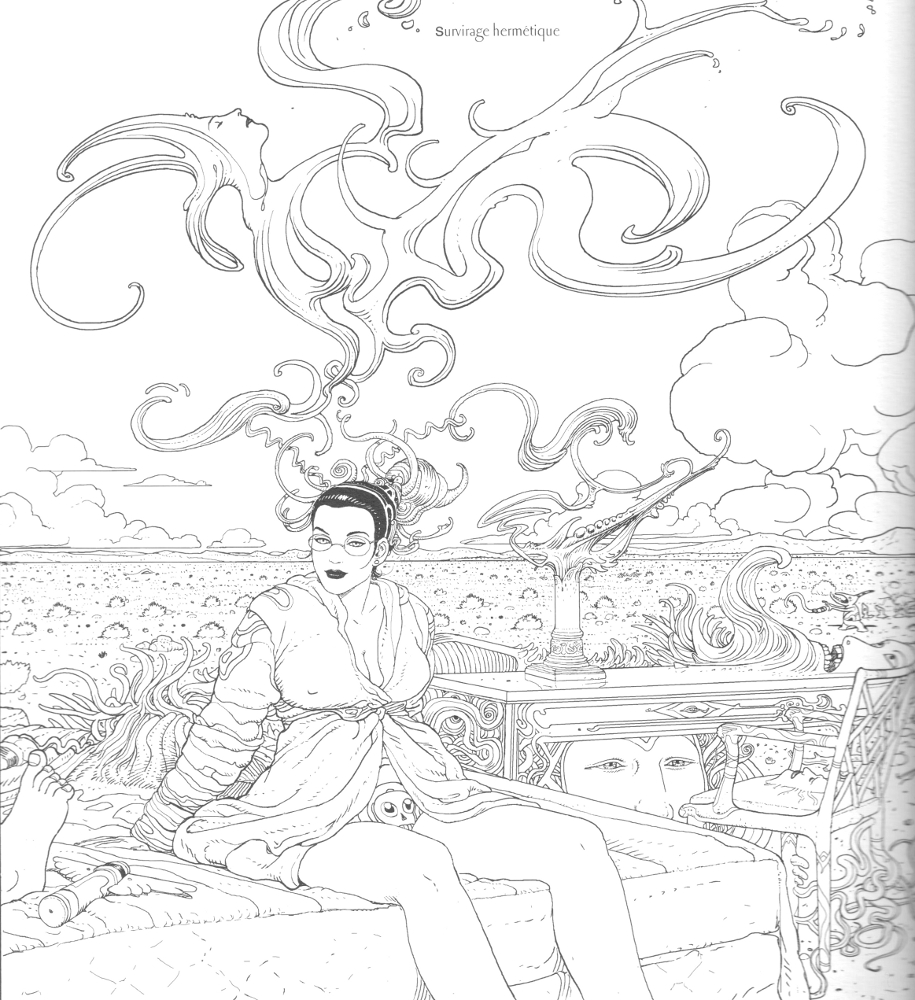

This prompts a personal mise-en-abîme in which the Major finds himself unstuck from the temporal flux, wandering the desert, which — literally as well as symbolically — was ever Giraud’s creative locus amoenus, only to be trapped in the clinical halls of a museum overseen by a dominatrix task-master, the Overturner. Here, he loses himself in his work or, as he describes one of the pieces on the walls, “plays with fire.” The tone is retrospective, describing a creator who, in the words of one of his creations, never delivered to the arid desert floor of his world the Elysian Fields promised in his prime.

This allegorical narrative is woven through with what is clearly personal detail. At one point, the Major expresses a wish to escape to “Good Old Earth,” more precisely the Mountrouge suburb of Paris where Giraud lived with his second wife, Isabelle. And it is tempting to see in the voluptuous Overturner a complex portrayal of his formidable wife and business manager. While superficially presented as a villain, she is simultaneously the most intriguing character in the book, acting the part of the artist’s dark muse and embodying his desire.

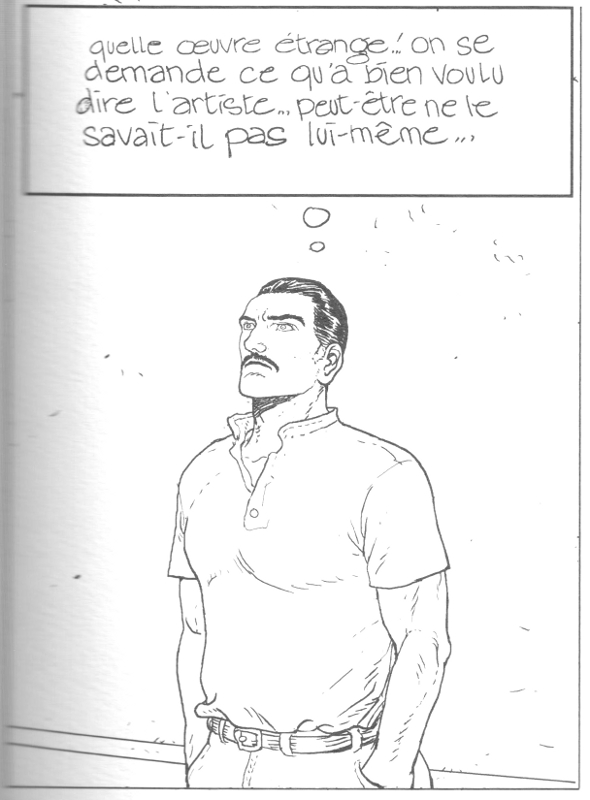

At one point, the action jumps ahead eleven years — eleven years which we sense have personal resonance — and we understand that the Major has spent that time passively as a slumping custodian in the museum of his own work. The initially exuberant and virile, if still menacingly inflected, picture above him (“Playing with Fire”) has morphed into an oppressive conglomeration of biological havoc, reminiscent of the work of Moebius’ fellow designer for Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), H. R. Giger.

Central to both compositions are the skulls that anchor much of the imagery in this book, as well as in its direct predecessor, the extended creative mediation 40 Days dans le Desert “B” (1999). The skull in art tends to signify vanitas, a symbol of the transience of life, and Moebius in one instance even makes use of the similarly consolidated motif of the artist working with Death looking over his shoulder, but he gives it all a disturbing personal spin.

The skull in these images is often at the center of the kind of mutating forms for which he is famous, the kernel animating the creative metamorphosis that is at the core of his art, and of his creative self-conception. Once beautiful and inspiring, even regenerative, at other times in his career barren and still, these mercurial forms turn tumorous in old age. Fatal.

As has ever been the rule of his art, Moebius knows he cannot escape. Yet he sees an out. The Major, on the run from the Overturner’s murderous rabbit henchmen (don’t ask), decapitates himself, leaving his body at their mercy (a charged representation of his troubled, always slightly alienated sexuality). Hilariously — the silly was ever a saving grace for him — his noggin drops down a rabbit hole, and as is the nature of such apertures, he changes.

As has ever been the rule of his art, Moebius knows he cannot escape. Yet he sees an out. The Major, on the run from the Overturner’s murderous rabbit henchmen (don’t ask), decapitates himself, leaving his body at their mercy (a charged representation of his troubled, always slightly alienated sexuality). Hilariously — the silly was ever a saving grace for him — his noggin drops down a rabbit hole, and as is the nature of such apertures, he changes.

From the resultant cancerous mass emerges once again the good old Major wearing his pith helmet, carrying his overnight bag. Meeting him there is his liberated, non-mustachioed alter ego from the ending of the original Garage, who takes him on a journey not toward Montrouge as he initially wishes, and not out of the dream in which he has been suffering, but toward the “six million” doors it still offers him. We thus leave them as they approach not our Good Old Earth, but another.

What better ending? The artist submitting his creativity as redemptive, finding it ever on the event horizon of the Other.