Earlier this week Caro discussed the ethics of Dr. Who. In the course of comments, Torchwood came up…and I discovered that the article about that show I wrote for the Chicago Reader in October 2008 has mysteriously vanished into the dreaded vacuum-of-perpetual-redesign. So, since it’s gone there, I thought I’d post it here. This is my original version, slightly different from the one that was published.

___________________________

Sci-fi melodramas have long inspired narrative compulsions in their devotees . Every episode of these shows leads, not to resolution, but to heaving, endlessly provocative streams of quasi-licit online fan-fic. The (largely) female viewers of these shows don’t just want to watch the characters — they want to pick them up, strip them down — to possess them and be possessed by them. Trite storylines and gaping plot holes are forgotten, to be rewritten as devotion, inspiration, and the beauty of orgiastic metatextual romance.

On the surface, Torchwood looks a lot like its predecessors. The plot, based around a group of super-secret operatives who protect Cardiff, Wales from aliens, is in fact, a perfect hybrid of Buffy, the X-files, Star Trek, and Dr. Who.

And therein lies its distinction. Torchwood isn’t so much a TV show as a fan-girl wet dream. Star Trek and Buffy merely inspired fan-fic; Torchwood is inspired by it. Fan fiction creates new stories for established characters— Torchwood is a spin off of the revamped Dr. Who. Fan fiction rewrites series continuity — a process sometimes referred to as retroactive continuity, or ret-con. Torchwood characters rewrite history and cover up their mistakes by using a memory wipe drug called — you guessed it — Ret-Con. Fan fiction writers will often introduce a “Mary Sue”; an author surrogate who wins over the cannon characters with her depth and general wonderfulness. Torchwood’s first season focused on Gwen Cooper (Eve Myles), a normal, everyday viewer surrogate who stumbles into the world of alien technology — and wows all the other characters with her depth and general wonderfulness,

But all that’s just icing. The main link between Torchwood and the fandom is sex. Specifically, gay sex. More specifically, angsty, hot guys who indulge in tortured romance and witty repartee as a prelude to gay sex.

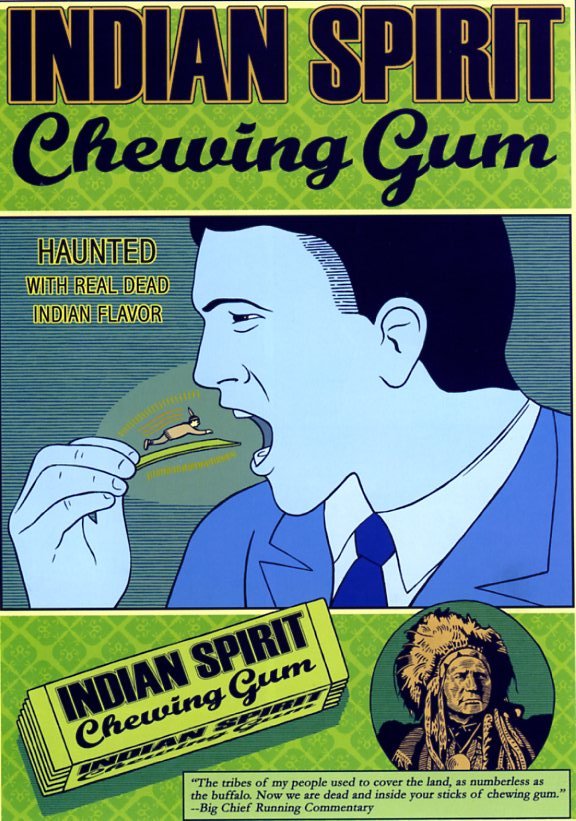

Everybody knows that guys love lesbian porn. The fact that many women like gay male porn is less well-established — but the evidence has been quietly mounting. Perhaps the biggest tween girl phenomena of the last 15 years is the spectacular success of shojo manga — romance comics from Japan, written by women for girls. Shojo narratives often center around romantic trysts between boys — there’s even an explicit sub-genre called yaoi, a word which is sometimes jokingly translated as “Stop! My butt hurts!”

There are huge fan-fic communities associated with almost every shojo title. But the obsession with gay sex is hardly confined to those fandoms. In the early 70s, female Star Trek fans started penning slash fiction, in which Kirk and Spock explore some of the repressed aspects of their relationship. With the Internet as a spur, slash fiction has metastasized. If you had a dime for every Snape/Harry Potter story, you’d be almost as rich as if I had a quarter for every Xander/Spike pairing.

Spike is, of course, the brutal, charismatic, ambivalently redeemed vampire who stole the show in both Buffy and its spin-off Angel. Not accidentally, the actor who played Spike, appears in the Torchwood second season debut as a brutal, charismatic, ambivalently redeemed time traveler named Captain John Hart. He and dashing series star Captain Jack Harkness (John Barrowman) have a history, and when we see them together for the first time in “Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang”, they stare soulfully at each other…then exchange blows…and then lock lips. The pounding rock music on the soundtrack is drowned out by millions of rapturous fan-girls flapping their arms and shouting “squee!”

The Captain Jack/Captain John relationship is definitely a series highlight, reveling as it does in the homoerotic elements of the hero/villain duality which most cultural products repress. When Captain John returns in the series finale, “Exit Wounds”, he declares that he wants revenge because Jack hasn’t spent enough time with him. It’s arch-villain as spurned lover — which gives you a whole new perspective on, for example, the Batman and the Joker, or, for that matter, George Bush and Osama Bin Ladin. Just get a room, guys.

For most male action heroes from Clint Eastwood to Martin Van Peebles to Keanu Reeves, masculinity equals emotional remoteness. Even the relatively effete Dr. Who (David Tennant) shows his nads by never quite being able to say “I love you.” In Torchwood, though, pretty much everyone is bi, and as a result the fear of feminizing emotional display is suspended. Captain Jack is a mysterious semi-reformed undying time-traveler with various tragedies in his past — in another show, he’d be all broodingly taciturn and repressed. Here, though, he’s flamboyant, flirting outrageously with middle-aged secretaries, babbling about his fetish for office spaces, and impulsively resurrecting his teammate because he can’t bear to see him go. He also cries when he’s sad and hugs those he loves and giggles when someone says something funny. And, in the second season at least, he’s in a stable, caring, and supportive relationship with his adorably dry teammate Ianto Jones (David Gareth-Lloyd.) In other words, because Jack occasionally engages in anal sex, he doesn’t have to constantly act like he’s got a pole up his ass.

This isn’t to say that Jack is always sympathetic. He’s often dictatorial, unpredictable…and, indeed, incoherent. If the best parts of Torchwood spring from its gender-bending roots in fan-fiction, its downsides also seem drawn from the fandom. The writers are way, way too enamored of drippy melodrama, on the altar of which they are willing to sacrifice even minimal consistency. Every episode, practically, ends in A Very Tragic Death — of a major character, a minor character, a space whale — it hardly seems to matter, as long as we can get everybody weeping. Even worse is the need to saddle every Torchwood member with a traumatic backstory. Jack’s past, which involves dead parents, lost brothers, and an ill-defined sepia-toned landscape, is hard to beat for idiocy. And yet, I think the prize has to go to Owen Harper (Burn Gorman), who, late in the season, acquires a never-before-mentioned, completely incongruous dead ex-fiancée.

The reliance on soap-opera tearjerker is especially frustrating because the cast is uniformly stellar. David Gareth-Lloyd as Ianto rarely has that much to do, but he really delivers — his deeply uncomfortable twitchiness when Jack first asks him out is one of the funniest things I’ve seen on television. Naoko Mori as the nerdy Toshiko Sato is also a gem; her subtle blend of innocence, eagerness and bravery, and her painfully unrequited crush on Owen, provide the series with most of its moments of real heartbreak. The best episodes — like the comic “Something Borrowed,” or “Adam,” in which Tosh and the assholeish Owen switch personalities — just draw into relief how great Torchwood could be if the actors weren’t so frequently saddled with duff scripts.

But that’s television, I guess. Torchwood isn’t quite great. But it is a watershed — the first show to take fan-fic to the mainstream . Unsurprisingly, Torchwood’s exploitation of a hitherto underserved fetish has resulted in excellent sales: its debut broke BBC audience records. With such success, there are sure to be imitators. “The 21st century is when everything changes,” as the Torchwood tagline says. The manporn deluge cometh.