I’m pleased to report that my one-act play “Crisis on Infinite Earths” premieres at the Pittsburgh New Works Festival this month. If you can’t make it to Pittsburgh but are curious what superheroes, saints, planets, and dinosaurs have in common, here’s the script . . .

(A church. The Virgin Mary stands on a pedestal surrounded by scaffolding and pulleys—or perhaps simply a rope across a flyrail. Three workmen enter, rolling a crate on a cart. ART is over fifty; BOB is in his thirties; CLIFFORD early twenties. During the scene, they will replace Mary with a statue from the crate. They begin by sliding the crate off the cart. The lack of conversation soon grates on Clifford.)

CLIFFORD: If you could have any superpower what would it be?

BOB: What?

CLIFFORD: If you could have any superpower, you know, like heat vision or seeing the future, that kinda thing.

BOB: I don’t know.

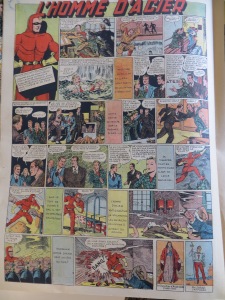

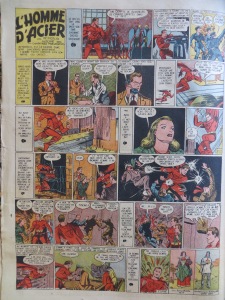

CLIFFORD: I’d get super-speed. Like the Flash. He moved at the speed of light. Imagine that. Finish this job in a half second.

BOB: Then what, sleep all day?

CLIFFORD: Yeah. But at light speed.

BOB: You’d be better off mind-reading or seeing the future or something.

ART: I’d want immortality.

CLIFFORD: That’s not a superpower.

BOB: Sure it is.

CLIFFORD: I mean like a superhero superpower. Only gods live forever. That doesn’t count.

BOB: What about Thor? He’s an Avenger.

CLIFFORD: So what would you pick?

BOB: Flying.

CLIFFORD: Everybody says flying. It’s so obvious. Pick something else.

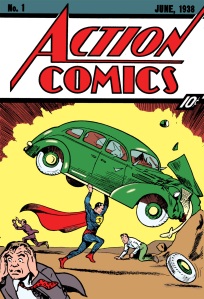

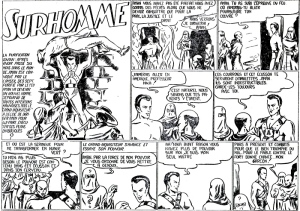

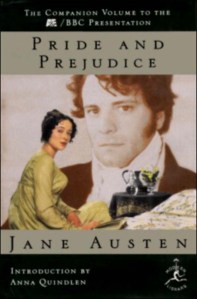

BOB: I’d be Superman. Best overall package. Flight, strength, invulnerability. X-ray vision.

CLIFFORD: But say you can only have one power, pick one.

BOB: I did.

CLIFFORD: Other than flying.

ART: Superman couldn’t fly.

CLIFFORD: Superman?

ART: He couldn’t fly.

CLIFFORD: Big guy in blue tights, cape, “S” on his chest?

ART: Not originally.

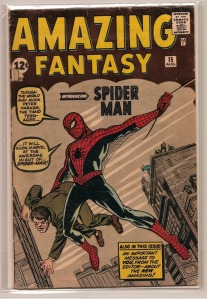

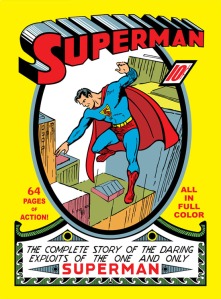

CLIFFORD: You ever see the first issue? He’s sailing right over a building.

ART: He was jumping over it.

CLIFFORD: You’re telling me Superman couldn’t fly, he just . . . hopped?

ART: Tall buildings in a single bound.

CLIFFORD: That’s just an illustration of his strength, of his leg muscles. He could jump over a building, he’s that strong.

ART: The original Superman did not fly. He jumped.

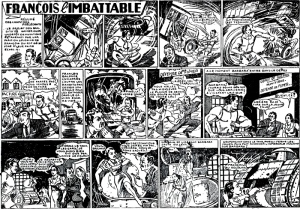

BOB: You mean like the Hulk?

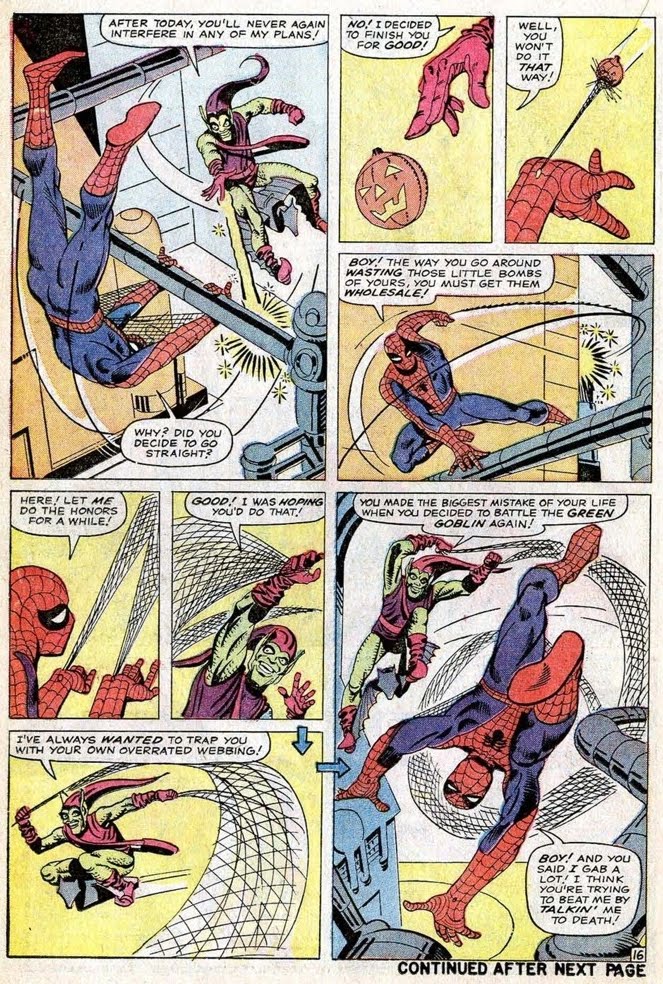

CLIFFORD: There, good example. The Hulk’s a jumper. You can tell by his posture. Bulky, no flight lines, no cape. Superman wouldn’t have a cape if he didn’t fly.

BOB: Batman doesn’t fly.

CLIFFORD: That’s different.

ART: I’m just saying after the first few issues they changed his powers. Okay? Now let’s get this lady on her feet.

(They begin to raise the new statue, but Art stops.)

Carefully. This isn’t just some hunk of rock. This is St. Philomena. My grandparents used to pray in front of this statue. This whole church was named after her. Show some respect.

(They raise the statue to a standing position and then step back to catch their breath, before starting to attach ropes to the other statue.)

CLIFFORD: Okay. So when Superman first gets to Earth, he can’t fly yet, he has to learn, he’s a toddler, that makes sense.

BOB: Superman didn’t get his powers till he hit puberty.

CLIFFORD: You agree with him? He couldn’t fly?

BOB: He couldn’t do anything. He was normal until high school.

CLIFFORD: No way. I had a box of my dad’s old Superboy comics. Superboy was a little kid and he had the suit and the cape, all the powers, everything.

BOB: And a flying dog named Krypto?

CLIFFORD: Yeah.

BOB: They got rid of him.

CLIFFORD: They got rid of Krypto?

BOB: They got rid of Superboy.

CLIFFORD: Who did?

BOB: I don’t know. Darwin. The new writers. They rewrote everything. Krypto got cut, Bizarro World—

CLIFFORD: So all those old comics, they’re saying they never happened?

ART: No, they just moved them to Earth 2.

CLIFFORD: Earth what?

ART: When superheroes got big in the 60’s again, they invented Earth 2 and put all the old stories over there.

CLIFFORD: They changed the past?

ART: They had to. Superman and Batman and all of them should have looked like me, old guys with gray hair and beer guts, but they didn’t. They looked more like you two. So they decided all the 30’s stuff happened on Earth 2.

BOB: Actually, they got rid of that, too.

ART: Earth 2?

BOB: All the alternate worlds. It was too confusing for new readers.

ART: What about the earth where all the superheroes are bad guys?

BOB: Gone.

ART: Batman’s daughter?

BOB: Gone.

CLIFFORD: What are you guys talking about?

ART: Supergirl?

BOB: There’s a new one now, only she was never from Krypton anymore.

CLIFFORD: How can they get rid of a whole planet?

ART: Krypton exploded.

CLIFFORD: I mean Earth 2.

BOB: That’s nothing. You know they got rid of Pluto?

ART: Why would the writers get rid of Pluto?

BOB: Not in the comic book, the real one.

CLIFFORD: Pluto? The planet Pluto? Who got rid of the planet Pluto?

BOB: I don’t know. Astronomers.

CLIFFORD: What, did they blow it up?

BOB: They excommunicated it. It’s just a chunk of rock now.

CLIFFORD: That’s like saying the sun’s not the sun anymore.

BOB: Pluto’s nowhere near that old. They only discovered it in the 30s. Same as Superman.

(Looking at St. Philomena)

I bet this thing is older than that.

ART: The whole church is. 1860s. My grandparents were married right over there.

BOB: I thought it was built in the 1960s.

ART: You’re thinking when they changed the name. When I was baptized here, it was St. Philomena’s.

BOB: Why did they have to change—

CLIFFORD: But Pluto was there. It was always there. Not knowing about it doesn’t mean it didn’t exist.

BOB: It didn’t exist to us. The same thing, isn’t it?

ART: I thought some committee or something put Pluto back.

BOB: Sort of, they turned it into a “dwarf” planet, not an official one.

CLIFFORD: So it’s back? Pluto is a planet again?

BOB: Yeah, but then they had to make some other ones too.

CLIFFORD: Some other what? Planets?

BOB: Like fifty of them, could be thousands though.

CLIFFORD: Planets?

BOB: “Dwarf” planets. They had to. They meet the requirements. It’s empirical now.

ART: You just mean asteroids? Out past Pluto.

BOB: The biggest is between Mars and Jupiter.

CLIFFORD: They put a new planet between––

BOB: It’s not new. They’ve known about if for like two hundred years.

ART: But it was never a planet before.

BOB: It was, for a half century almost, almost as long as Pluto, before the Victorians got rid of it.

CLIFFORD: Planets are permanent. They’re absolutes. You can’t change absolutes.

BOB: Absolutes change constantly.

CLIFFORD: Name one.

BOB: The sun used to revolve around the Earth.

ART: That’s true. The church said so.

CLIFFORD: That’s different.

ART: It used to be flat.

CLIFFORD: Those weren’t changes, they were mistakes. Before they invented science.

BOB: Einstein said the speed of light was a constant. They changed that.

CLIFFORD: They changed their minds.

ART: The same thing they did to the saints. That’s how Philomena got downgraded to the basement. This church wouldn’t be called Mary of the Assumption right if the Vatican hadn’t changed its mind.

CLIFFORD: What did they do to the saints?

BOB: And the dinosaurs. Remember Brontosaurus? Big green guy, used to sit around in swamps because he wasn’t strong enough to lift its own body? Now they got them marching in herds with hollow bird-bones and whip-action tails.

CLIFFORD: What did they do to the saints?

ART: They got rid of them.

BOB: You know T. Rex looks like a giant chicken now?

CLIFFORD: Who did?

ART: I don’t know. The Jesuits.

BOB: He’s a girl, too. T. Rex is a girl.

CLIFFORD: The Jesuits got rid of the saints?

BOB: And a scavenger, completely harmless.

CLIFFORD: All of them?

ART: Like fifty. They have a special committee do it.

BOB: Those big jaws, they’re only for ripping up dead stuff it finds lying around now.

CLIFFORD: How many are left?

ART: Thousands still. They just thinned the herd.

CLIFFORD: Does the pope know?

ART: Some of the saints were only legends. Like Philomena here. My parents said this was her spot till the old pastor had her taken down. He said some nun dreamt up the whole story after bones were found in a mismatched grave. Philomena never existed. Lots of the old saints didn’t.

CLIFFORD: You mean like Santa Claus—St. Nick.

ART: I mean like St. Christopher.

BOB: Or Brontosaurus.

CLIFFORD: I have a St. Christopher’s medal.

BOB: Brontosaurus never existed. Someone put the wrong skull on a sauropod skeleton and made up the name.

CLIFFORD: My aunts gave it to me. They used to pray to him. I used to pray to him.

BOB: Hey, you know they found the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs?

CLIFFORD: Does that mean none of my prayers counted? Are the cuts retroactive?

BOB: Started the ice age.

ART: They changed it before you were born.

CLIFFORD: Oh my God.

BOB: It’s in Mexico.

CLIFFORD: I was praying to a canceled saint.

ART: My parents still pray to Philomena. The church only took her off the official calendar.

CLIFFORD: What’s the point of praying to someone who doesn’t exist?

ART: St. Christopher never existed now, after the church rewrote the history, but people still like the story of him carrying baby Jesus across a river on his shoulders. It’s a good story.

CLIFFORD: But it’s not true?

ART: It’s a metaphor.

CLIFFORD: I was praying to a metaphor?

BOB: That’s nothing. The Victorians thought T. Rex was a giant bullfrog. Imagine growing up reading about hopping dinosaurs. Pterodactyls used to have snake necks. Iguanodon was a giant iguana—with its thumb claw on the end of its nose. No wonder they died out.

ART: The iguanodons?

BOB: The Victorians.

ART: The Victorians didn’t die out, they. . .

BOB: Evolved into birds?

ART: Evolved into us.

BOB: Same difference. They’re gone. It’s survival of the fittest. Victorians, Brontosaurus, Pluto, Saint Christopher, Superboy—Darwin got them. Darwin dropped an asteroid on the whole lot.

ART: You can’t say something that never existed died out.

CLIFFORD: Dinosaurs existed.

ART: Superheroes didn’t. And you’re not talking about changes in the past. You’re talking about changes made in history, changes in the history of history.

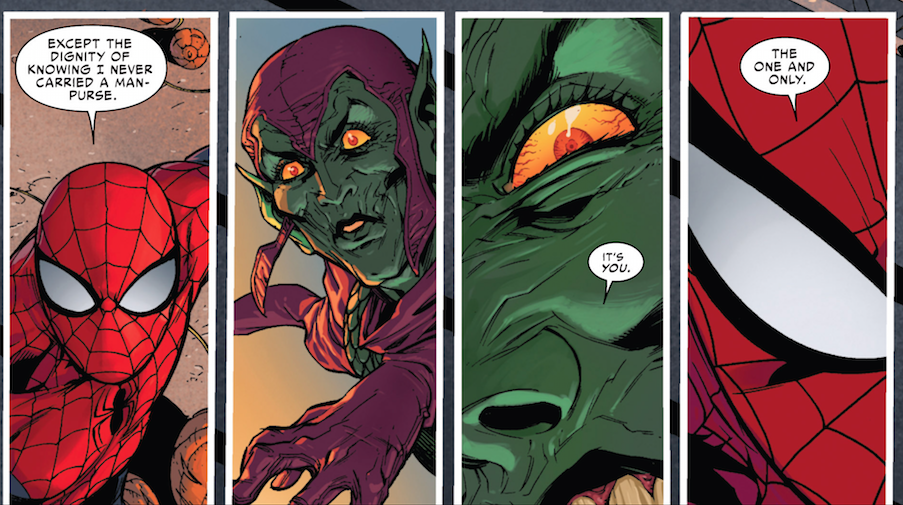

BOB: Ideas evolve. The good ones, the best stories, they keep reproducing themselves. Like now there’s a new Superboy.

CLIFFORD: You said they canceled him.

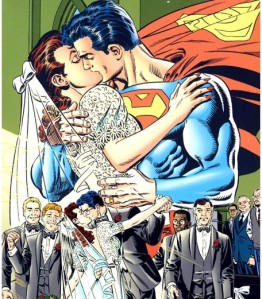

BOB: It’s not really Superboy. He’s a younger clone of Superman they made when he died.

CLIFFORD: How can they say Superboy died if he never existed now?

BOB: Not Superboy, Superman.

CLIFFORD: Superman died?

ART: That’s ridiculous. He was invulnerable.

BOB: Not to Kryptonite. Even the old Superman would have died of that.

CLIFFORD: Superman died?

BOB: That stuff’s real too, Kryptonite. It’s on the Periodic Table.

ART: One of those new elements they discovered? They named it from the comic book?

BOB: An old one. The Victorians found it.

ART: How could—

CLIFFORD: Don’t you mean the actor who played him died? The one who shot himself?

BOB: He didn’t shoot himself, he fell off a horse, and no, I don’t mean him, I mean Superman, the Earth 1 Superman.

ART: That supposed to be us, right?

BOB: Only it’s just called “Earth” now. The old Superman, the Earth 2 Superman, they erased his whole universe and sent him into limbo after all the other alternate Earths collapsed into Earth 1.

CLIFFORD: So now there’s no Superman anymore, just some clone running around?

BOB: No, they brought Superman back. He had different powers for awhile. And a ponytail.

ART: You mean they rewrote history again, wrote out his death?

BOB: The computers in the Fortress of Solitude had a seance or something.

ART: They resurrected him? Superman was dead and they brought him back to life? It was a miracle?

(Conversation halts as young priest enters.)

PRIEST: Well. How are things coming along here?

ART: Good morning, Father.

(Bob and Clifford greet him shyly and wordlessly.)

PRIEST: Hello, gentleman. I see Philomena’s happy to be out and about. No more limbo for this little girl. You can’t keep a good saint down, can you?

ART: No, Father.

PRIEST: I wouldn’t mind seeing all the rest of that statuary back up here where it belongs. No reason Mary has to have all the best pedestals, right? I was thinking we would move her outside, into the garden maybe. Or switch her with one of the front statues. If that’s not too much to ask. Lord knows there wouldn’t be a church without men like you to do the heavy lifting.

(Awkward pause)

Well. I don’t want to hold you gentleman up. You’re doing a wonderful job.

(He exists.)

CLIFFORD: God. That guy can’t be much older than me. Can you imagine taking communion from him? Or confession.

BOB: I can’t imagine taking them from anyone.

CLIFFORD: You’re not . . .

BOB: Not since, I don’t know, high school I guess. Used to get the body of God stuck to the roof of my mouth every Sunday.

CLIFFORD: What happened in high school?

BOB: I don’t know. Puberty. I evolved. My superpowers came in.

CLIFFORD: You started flying?

BOB: I started thinking. It stopped making sense, Purgatory, immaculate conception, transubstantiation.

CLIFFORD: But you still believe in . . .

BOB: It was so much easier when I was little and I could just believe whatever my parents believed. Hell, I was an altar boy.

CLIFFORD: Hey, me too. I got to ring that little bell during service. I thought it was to keep people from falling asleep. I even thought about being a priest. My parents wanted me to, but my pastor didn’t think it was such a great idea. I wasn’t, you know. Called.

ART: (Stopping work with sudden annoyance) It’s not fair.

CLIFFORD: What?

ART: Earth 2. It’s not fair. It was just “Earth” in the 30s, right?

BOB: Yeah. They couldn’t know the 60s writers were going to reinvent everything.

ART: But it’s wrong. Naming the second Earth “one” and the first Earth “two” when the old Earth was where all the original superheroes came from. It should have been “Old Earth” and “New Earth.”

CLIFFORD: Oh, right. Like the Bible.

ART: Well, not . . .

CLIFFORD: Old Testament, New Testament.

ART: That’s not what—

CLIFFORD: Because that would make sense. Jesus was Jewish, and he was rewriting the Old Testament. He was upgrading it.

ART: It’s not like that at all. The Old Testament is still there. It’s the foundation. They built on top of it. The Torah. They just changed the name is all. And moved some of the sections around, most I think, and, what was it? They cut—

BOB: Superman was Jewish.

CLIFFORD: No way!

ART: He was created by two Jewish guys, but that’s not the same as—

BOB: His Krypton name is Kal-El. “El.” That’s Hebrew for “God.”

ART: They made that up. The original Super—

CLIFFORD: What’s “Kal”?

BOB: Short for Karl, German root for “man.”

ART: “Godman”? You’re saying Superman is a “Godman,” like, like…

CLIFFORD: Yeah! Like Jesus. I get it. He’s an alien. He comes from the heavens and is raised by humans. Oh my God. It’s the same as Tarzan. Or Harry Potter. Jesus Christ was raised by muggles.

BOB: I was actually thinking about the other godmen around then.

ART: Around when? Jesus?

BOB: It was a crowded gene pool. Mithras, Osiris, Dionysus, Zoraster . . .

CLIFFORD: These are superheroes?

BOB: . . . Adonis, Attis . . .

ART: Adonis? Are you kidding?

BOB: . . . Horus, Aion—did I say Osiris?

ART: Those are just old gods, demigods, like Thor.

BOB: Right, Thor, he was a son of God, too.

(He points at the Mary statue)

Most of them are born from virgins, in mangers, under holy stars. They perform miracles, heal the sick, turn water into wine, raise the dead. Some lead twelve disciples around until they get arrested and executed on trees. Then they come back to life and save humanity.

CLIFFORD: Which “Earth” is this?

ART: Those are knock-off myths. They were written after Jesus.

BOB: The church admitted they came first. They said the devil planted the stories into older religions so people would be confused when the real Son of God showed up. They even put church holidays on top of the originals. Like Mithras. He was born December 25th.

CLIFFORD: Mithras—didn’t he fight Godzilla?

BOB: There were even three shepherds there. And Easter. March 25th, that’s the resurrection of Attis.

ART: Where the hell are you getting this stuff?

BOB: It’s all over the place. Google “ancient godmen” and you’ll—

ART: Oh. The Internet. Right. I get it.

BOB: And books. It’s in lots of books. Same place you get any religion. Same as the Bible.

ART: The Bible is not “a book.”

BOB: That’s all the word means. “Books.” Look it up. The church picked its favorite stories and put them in one volume. Like Reader’s Digest. They could have done it with Mithras or Attis or any of—

ART: You’re really saying Jesus came after this stuff? That’s insane. Jesus—

CLIFFORD: I get it! He was an adaptation, a mutant. Darwin weeded out all the other godguys and put Jesus in charge of the herd. It’s natural selection.

ART: It’s got nothing to do with selection. Those other gods are characters in stories. They’re make believe. Jesus has a real history. The Gospels are eyewitness accounts.

BOB: Nobody wrote a gospel till the 70s. Jesus died in the 30s. And the church cut most of them anyway—like a hundred and twenty gospels they threw out. Some of them had little Jesus killing playmates during temper tantrums and raising his pets from the dead.

CLIFFORD: Wow. Like a toddler Superboy.

BOB: Exactly.

ART: No, not like Superboy. It’s nothing like Superboy. Superboy is made-up. He never existed even before he never existed.

CLIFFORD: So Jesus was a little bad ass, huh?

BOB: That’s nothing compared to some of the other gospels.

CLIFFORD: Like what?

BOB: He had sex with Lazarus.

CLIFFORD: No way! Jesus was gay?

ART: Jesus was not gay.

BOB: He was bi.

ART: Jesus was not bi.

BOB: Batman was bi.

CLIFFORD: Batman was bi?

ART: Batman was not bi!

BOB: That’s why they had to break him and Robin up. A millionaire “bachelor” living alone with his young “ward.” Do the math.

CLIFFORD: (After a silent pause as he “does the math”) Oh my God! They were gay.

ART: It was the 50s. It was another era. Those people were paranoid about everything.

CLIFFORD: So Lazarus, did he become Gay Jesus’ sidekick?

BOB: Probably not. They think that gospel might be fake.

ART: Of course it’s fake. The church only kept the real ones. Those other Gospels aren’t Gospels, they’re just stories. That’s why they got rid of them.

CLIFFORD: So it is natural selection. The true stuff won out.

BOB: It’s got nothing to do with “truth.” The gospels in the bible are just the ones that fit the church’s needs at the time.

CLIFFORD: Right. They were the best adapted for survival.

ART: The only need they fit was history.

BOB: Which was up for grabs. Every sect had its own history about Jesus.

CLIFFORD: So God weeded through all the different Jesuses till he got the best one. The other Jesuses, the “dwarf” Jesuses, they died out.

BOB: They didn’t—

CLIFFORD: God decides everything, right? So he must have selected the Gospels he liked or they wouldn’t have made it into the Bible.

BOB: God didn’t—

CLIFFORD: It’s like finding a bunch of bones. God’s showing us the right way to put the pieces together, which don’t belong. It’s like evolution. He’s guiding us.

BOB: God doesn’t guide evolution. That’s the whole point. It just happens. If God is controlling it, then it’s not natural selection. It’s supernatural selection.

ART: How do you know God isn’t controlling it? He invented it.

CLIFFORD: Evolution?

ART: Life. Scientists have no idea how it began. There’s nothing that comes close to explaining it. And since God knows the future, He knew what was going to happen. He knew everything that was going to evolve and when. How’s that different from controlling it?

BOB: Because you don’t have to believe in God to make sense of nature. It works without him.

ART: That’s not the same as saying that there is no God.

BOB: I didn’t say there wasn’t a God.

CLIFFORD: You said there wasn’t a Superboy.

BOB: I said they wrote Superboy out of Superman. It was a stupid story, so they killed it.

ART: The same way they wrote God out of nature? What’s so stupid about God?

BOB: I didn’t say God was stupid! I said he doesn’t guide anything. Do you think he woke up this morning and decided Philomena was coming out of the basement today?

ART: In a way, sure. He may not be micro-managing everything, but progress isn’t accidental. Things happen for a––

BOB: We’re not answering a call from God. The only call I got this morning was from you. You want me in a church moving statues? Fine. You want me pouring cement? Fine. Just don’t tell me this chunk of rock is different from any other. God didn’t make it. God doesn’t care about it. Shatter the thing into a million pieces, and it won’t make any difference to Him.

ART: I don’t know what planet you live on, but this is Earth. God made it and everything on it. Including this church. I’ve been a member of this congregation since I was born, and I’ll be a member after I die. When you and all your stupid ideas are extinct, this “chunk of rock” will still be standing.

(They work in tense silence for a long while. The tension gets to CLIFFORD who stands between the other two, directing his comments to their backs.)

CLIFFORD: So I’m rethinking the whole super-speed thing. Maybe I should go for super-strength? Or invulnerability. What do you think?

(He waits but gets no response.)

Isn’t Krypton a kind of ice planet, like in an ice age? Like Pluto. You’d have to be invulnerable to live there.

(No response)

They ought to make up some new powers, don’t you think? Stop recycling all the old ones. New superheroes too. Like they do with the saints. They make new ones all the time. Aren’t they making the pope one now?

BOB: A saint? He’s not even dead yet.

CLIFFORD: Not the new pope, the old pope. The dead pope. The new pope, the Earth 1 pope, he’s making the Earth 2 pope a saint.

ART: You don’t just make somebody a saint. It’s not like writing a comic book. A committee has to weigh evidence. It takes years.

BOB: Evidence of what?

ART: Miracles.

CLIFFORD: What do they have to do, like fly and walk through walls and stuff?

ART: They cure people.

BOB: So the pope has to come back to life and heal lepers?

ART: People pray to him and he answers them.

CLIFFORD: So one answered prayer and he’s in? He’s a saint.

ART: Two. So it’s empirical.

BOB: Empirical?

ART: Yes. Empirical. That’s how they sainted Mother Drexel back in 2000.

CLIFFORD: What did she do?

ART: Cured a deaf baby. Doctors couldn’t explain it, but the parents said they had prayed to Drexel.

BOB: How did they know to pray to her if she wasn’t a saint yet?

ART: They saw her special on PBS.

CLIFFORD: Now there’s a superpower. No wonder Saint Nick died out.

ART: Saint Nicholas didn’t die out.

CLIFFORD: Santa Claus?

ART: He’s still a saint. Biggest in the Russian Orthodox Church.

CLIFFORD: Fat guy, raised by elves. Lives on the North Pole. He’s still a saint?

ART: Not that part of the story.

BOB: Superman lives on the North Pole.

CLIFFORD: So what’s out, flying reindeer, the toy shop, what?

BOB: In the Fortress of Solitude. They’re neighbors.

ART: The original Saint Nicholas lived, I don’t know, in Roman times. He was rich and gave it all away. They say he threw a bag of gold through a poor father’s window each time the guy was about to sell one of his daughters into prostitution, so he wouldn’t have to.

CLIFFORD: That got him sainted? No stockings, no deaf babies, no Burgermeister Meisterburger? Why don’t we put him up there? With a sack of toys and a chimney.

ART: He didn’t go down chimneys.

CLIFFORD: So what miracles could he do?

ART: They don’t apply that standard to the old saints.

BOB: You said a committee weeded them out.

ART: Any saint that wasn’t actually a person, a historical person, not a legend.

CLIFFORD: But the real ones don’t have to have miracle powers?

ART: Some do. Saint Olaf, his body kept coming out of its grave, and a spring started running from the spot—no, it was blood maybe. He converted a lot of people, too. They can’t verify them though.

CLIFFORD: The conversions.

ART: The miracles. His conversions he did on a chopping block. Believe in God or your head came off.

BOB: They let him stay a saint?

ART: They had to. He was real.

CLIFFORD: What kind of standard is that?

ART: You can’t revoke sainthood. It’s permanent, like, like circumcision.

CLIFFORD: You said they tossed out fifty.

ART: It used to be by popularity; all the early martyrs got in that way. Stories would go around, getting bigger and crazier, and most of them started from something, a real person, but the ones that weren’t they get rid of.

CLIFFORD: But you can still pray to them?

ART: Sure.

CLIFFORD: So they’re “dwarf” saints.

BOB: Where do they live? Pluto?

ART: They don’t live anywhere. They’re not—

CLIFFORD: What if they change their minds again? What if someone digs up a bunch of St. Christopher bones?

ART: Then I guess they’d have to reinstate him.

BOB: Where’s he go in the mean time? Earth 2?

CLIFFORD: This is so unfair. I bet St. Christopher answers way more prayers than Drexel.

BOB: He just goes by “Christopher” now.

CLIFFORD: Look at the odds. People have been praying to him for centuries. He’s probably racked up a dozen deaf babies.

ART: Those are coincidences. Or the Holy Spirit acting through—

CLIFFORD: He got me through eleventh grade science—the unit test on animal classification.

BOB: What about Philomena?

CLIFFORD: (To himself on his fingers) Plants, lichens, invertebrates, vertebrates, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals.

ART: She has lots of miracles. Cancer and heart disease and a bunch of stuff. Plus back in the second century, she chose torture and death over marriage to the Roman Emperor.

CLIFFORD: Wow. I still remember that.

(A beat, then he crosses himself)

BOB: She didn’t exist.

ART: I mean—that’s the story they tell about her. Officially she’s not real, but she’s still popular. There are all kinds of shrines and foundations, websites. There’s a revival.

BOB: That’s why they want her up here again?

CLIFFORD: Like an endangered species act?

ART: It’s the new pastor’s idea.

CLIFFORD: Wait. That young guy? He’s the pastor? I thought he was like, a sidekick or something.

BOB: Are they going to rename the church again too?

ART: They shouldn’t have changed it to begin with. It upset a lot of good people. My grandmother, my dad says she cried for months.

CLIFFORD: They should name it St. Drexel. She’s got miracles and she was real. She’s a super-saint.

BOB: Drexel. As in the millionaire Drexels? From Philadelphia? No wonder they sainted her.

ART: She didn’t have millions. She was a nun. She gave it to charity.

BOB: All of it?

ART: They have to take a vow of poverty.

CLIFFORD: I thought it was celibacy.

BOB: She was a millionaire, and she gave it all up to be a nun? That is a miracle.

CLIFFORD: It’s like discovering a new species. The Supersaintasarous.

BOB: You hear they dug up a new plant-eating Velociraptor in Utah?

CLIFFORD: What about John Paul 1? Are they sainting him?

BOB: It has feathers.

ART: No, but John 23 probably. Some people are still sore about Vatican II though.

BOB: Everything has to have feathers now.

CLIFFORD: What about Vatican I?

ART: That was in the 60s, the 1860s, when the pope became infallible.

BOB: It’s not technically a Velociraptor though.

CLIFFORD: Infallibility! That’s the superpower I want.

BOB: It’s a missing link between carnivores and herbivores.

ART: And you don’t think God had anything to do with that? These animals just rose up by themselves. What are the odds?

BOB: Pretty good considering plants started growing around the same time.

ART: And that’s just a coincidence? Plant eaters just happen to show up when the plants do.

BOB: You really have no idea what natural selection is, do you?

ART: I know enough to recognize the hand of God when it’s pointing me in the face.

CLIFFORD: Hey, which came first, the Brontosaurus or the egg?

BOB: It wasn’t a—

ART: The Brontosaur.

BOB: The egg.

CLIFFORD: Then where did the Brontosaurus come from?

ART: God.

BOB: Oh, please. Was it pulling a plow in the Garden of—

CLIFFORD: So where’d the egg from?

BOB: From the proto-Brontosaurus.

CLIFFORD: What’s—

BOB: The animal one step behind on the evolutionary ladder. Brontosaurus was its mutation.

ART: There, see? A ladder. You can’t build a ladder one rung at a time. It has to touch the top before you can step on it. It’s predetermined.

BOB: It’s a figure of speech.

CLIFFORD: A metaphor.

ART: It’s God.

BOB: Okay, so say it’s a ladder. What’s next? What’s the next mutation God has planned?

ART: You think I have the power to read God’s mind?

BOB: You think he cooked up the omnivorous ex-Velociraptor right after sprouting new plant life in Utah. So look around. What’s on the agenda? Bigger stomachs? A third eye? Disposable thumbs?

CLIFFORD: But no superpowers, right?

ART: Smaller brains. Weed out the people wasting everybody’s time thinking up stupid stuff.

CLIFFORD: It would be such an obligation. I’d want something that only affects myself.

BOB: If God didn’t want me thinking, why’d he make me like this? Maybe I’m the next rung.

CLIFFORD: Like celibacy.

ART: Or you’ll die out. Not all mutations are good ones. Most of them are useless freaks.

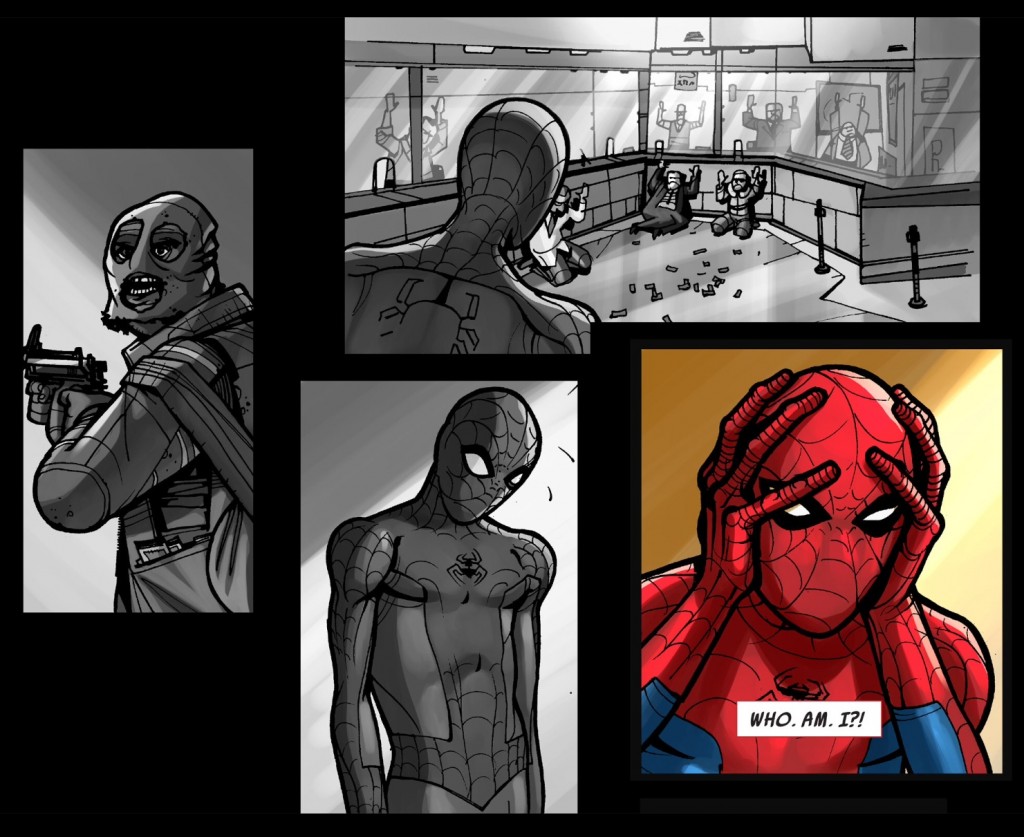

CLIFFORD: Yeah, they’re like curses. That was the whole point of Spiderman. He’s this sad sack loser. A radioactive spider bites him, and when he tries to cash in on his mutant powers, he lets some random bad guy go, and next thing the guy murders his uncle. What are the odds?

(Bob is about to speak but Clifford cuts him off.)

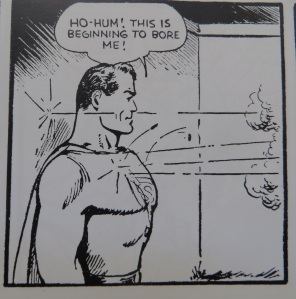

Or Bruce Banner. He saves some stupid kid from getting hit with gamma radiation, and so he has to spend the rest of his life turning into the Hulk—a big toddler-brained Frankenstein. What kind of deal is that? Even Superman must get fed up with it. When does he get a night off? His super-hearing’s always picking up someone screaming for help. No wonder he moved to the North Pole.

ART: So what powers do you want?

CLIFFORD: I don’t. It would be way too much responsibility. You’d have to give up everything.

BOB: It’s not the priesthood. Superheroes can—

CLIFFORD: You’d have no life. Even if you just wanted to fly, that would mean getting people off burning rooftops al the time, swooping in where the rescue ladders can’t reach. Forget privacy. You’d have to move somewhere crowded to maximize your rescuing potential. Vacations, evenings off, naps—how can you sleep if it means somebody dies? You’d be a savior 24/7.

ART: You’d be a god.

CLIFFORD: I couldn’t handle it. I just want to stay normal.

(Clifford resumes working. Bob and Art, uncomfortable to be sitting without him, join in.)

ART: Well you’re too late anyway. God already gave you superpowers. We’re the same as Drexel.

CLIFFORD: We cure deaf babies?

ART: We got money.

CLIFFORD: That’s a superpower?

ART: It’s all Batman had.

CLIFFORD: I’m not a millionaire.

ART: Neither was Drexel after she gave it away. Same for Saint Nicholas. Lots of the saints weren’t rich, but they gave what they had. How much do you give away?

CLIFFORD: To the church?

ART: To anything.

CLIFFORD: I don’t know. I’m saving for college. But I give, sometimes.

ART: How much do you spend on yourself, after the necessities, the minimum you need for survival?

CLIFFORD: I have no idea.

ART: You got a computer? How many sets of clothes? Air conditioning? How much does your car cost?

CLIFFORD: A drive a twenty-year-old Saturn, okay? It’s a piece of crap. I blew fifty bucks on a tire last week—money I don’t have.

ART: Fifty bucks. That would have saved a kid’s life. Food for a month. You could save tons of people.

CLIFFORD: I can’t fly around the world handing out cash. I can barely pay my rent.

ART: Every time you spend money on yourself you’re not spending it on somebody starving to death, or freezing, or whatever. You have powers. You’re just not saving people with them.

BOB: I don’t see you tossing bags of money through windows.

ART: Didn’t say I was. I got a mortgage, two kids in college. Family comes first.

BOB: You think Jesus cares more about your family than other people’s?

ART: You don’t even believe in Him.

BOB: I’m talking about you. Do you think your family is more important than other people?

ART: Than strangers? I can’t care about people I don’t know.

BOB: Why not?

ART: Because I don’t know them.

BOB: But you think Jesus cares about them.

ART: Jesus is God. I’m just human.

BOB: So it’s the species. We’re hard-wired not to care.

ART: It’s got nothing to do with caring. It’s the way we’re made.

BOB: So God gave us brains that can’t care about strangers? What kind of adaptation is that?

ART: It’s normal. God doesn’t expect us to—

BOB: A tsunami wipes out a million people? A million people, that’s what, three hundred times more than on 9/11? Am I three hundred times more upset? I can send money, I donate, but I don’t feel anything personal. I don’t break down like I did when my dog died. A dog. I give more money to the SPCA than I give to UNICEF. Tell me we’re not the most evil species that ever evolved. You think God planned us? He should drop another meteor. We’re just animals. We’re animals with the ability to recognize that we’re animals. That’s our superpower—

ART: Whoa! Carful with her!

(Bob grabbed the rope and they have no choice but to join him. In a moment, they have the Philomena up and step back winded.)

CLIFFORD: Drexel wasn’t an animal.

BOB: Drexel’s a saint. A super-saint. We’re a lesser species.

ART: Okay. We’re “dwarf” Drexels then, or, no, we’re proto-Drexels, one step behind on the evolutionary ladder. She’s our mutation.

BOB: So?

ART: So we helped make her. We’re part of the process. God’s process. Drexel couldn’t have gotten up there without us.

(Bob and Clifford look up again, as though seeing the statue for the first time. The priest enters, sees them, then the statue.)

PRIEST: Oh my. I had no idea. You did that so quickly. I didn’t think . . .

(Looking at the Mary on the ground, and then up at Philomena.)

I’m so sorry. I don’t know how . . . I just got a letter from the bishop. Today. This morning. Just now. I assumed—we all just assumed . . . The bishop it turns out, he doesn’t agree with, I mean, he’s not in agreement. About the statue. Philomena.

(Finally spitting it out)

The statue has to be taken down. We’re not allowed to display it in the church.

(Looking at them fully)

I’m so sorry.

ART: (After an awkward pause) Should we put the Virgin back up?

PRIEST: No. Ah, not yet. Let’s wait and see, okay? There might be another statue downstairs we can use in this spot. With the bishop’s permission. He’s very old, I’m afraid. He doesn’t like new pastors coming in and turning everything upside down. I hope you understand.

(The men smile and nod.)

ART: So take them both downstairs.

PRIEST: Yes. Please. For now. We’ll be able to tell you soon what’s going to go up there. I’m sure we will.

CLIFFORD: St. Christopher maybe?

PRIEST: I’m sorry?

CLIFFORD: Maybe you have some St. Christophers down there in the basement?

PRIEST: Maybe. Probably. There are so many down there. Why? Do you like him?

CLIFFORD: (Thinking a moment) Not really.

PRIEST: Oh.

ART: We’ll get right on it, Father.

PRIEST: Well. Thank you. Thank you again.

(He exits. The men are silent, looking back and forth between the two statues and the job ahead of them now. They begin.)

CLIFFORD: You got to feel bad for her. Imagine going from sainthood back to basement limbo. It would piss me off.

ART: They closed that.

CLIFFORD: The basement?

ART: Limbo.

BOB: It was real?

ART: All the Old Testament patriarchs lived there. Solomon, David, Moses. And all the unbaptized babies. It was too confusing for new converts, so they moved them all up to Heaven.

BOB: I thought they were all in Hades?

ART: Hades doesn’t exist.

CLIFFORD: They got rid of—

ART: You’re thinking Pluto, god of the underworld. The real one is called Hell.

BOB: Whatever. I thought unbaptized people went there.

ART: Limbo’s a subsection of Hell—but a nice one, no torture and stuff.

CLIFFORD: Why not get rid of Hell?

ART: There’s been talk.

(The Mary statue is in position to be lowered into the crate.)

Nice and easy and now. She’s having a hell of a day too.

BOB: You know they had the original Superman come back and try to restore Earth 2?

ART: The 1930s one?

CLIFFORD: Wouldn’t that mean wiping out Earth 1? Our Earth?

BOB: I guess so.

CLIFFORD: Destroy the whole world?

BOB: Yeah.

CLIFFORD: So they made him the bad guy? Superman’s the bad guy?

ART: Can you blame him? Who wouldn’t want their old world back?

CLIFFORD: But it’s Superman. That’s so . . .

ART: Sacrilegious?

BOB: That’s what the popes did to the old godmen, when Rome went Christian, they made all the old saviors demons. Literally sent them to Hell. One day you’re on top of the world, next they’re pulling down your statues. Imagine what that felt like.

ART: He didn’t feel anything. He never existed.

CLIFFORD: But his followers did. Think of them.

BOB: The Romans burnt every book that wasn’t part of the new history. They martyred anyone who couldn’t adapt.

ART: (Mostly to himself) I’d feel worse for Superman.

BOB: (Also to himself) It was like a meteor hit.

ART: First his whole race is wiped out on Krypton.

BOB: Instant Dark Ages.

ART: And then he loses his Earth.

BOB: Pushed civilization back a dozen rungs.

ART: He’s not even the last of his kind anymore.

BOB: Like an ice age.

ART: He’s not anything. He never existed, and he knows it.

BOB: Just bones to sort out.

ART: Can’t get more extinct than that.

BOB: Nothing’s immortal forever.

(Bob and Art fall into silence while Clifford continues to look back and forth at them. They begin to exit while rolling the cart out.)

CLIFFORD: So can he still fly?

(Lights fade. END.)