Editor’s Note: This essay was originally written for Chris Gavaler’s superhero class. We’re pleased to be able to reprint it here.

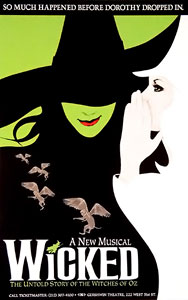

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, published in 1900, has captivated American culture and spawned numerous book, film, and stage adaptations which play with the original narrative. The novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire was brought to the stage and became one of the most famous musicals of all time. Wicked: The Untold Story of the Witches of Oz by Steven Schwartz premiered on Broadway in 2003, and a national tour directed by Joe Mantello recently visited Altria Theater in Richmond, VA for performances in April and May of 2014. This twist on the traditional Ozian tale presents the Wicked Witch of the West as the hero, using her powers to fight an oppressive regime. Her narrative mimics many plot elements in Gladiator, a novel by Philip Wylie; Superman Chronicles, a comicbook collection by Jerry Siegel; and Zorro, a film directed by Fred Niblo. All three of these draw from the superhero genre, borrowing a set of standard tropes identified by Blythe and Sweet in “Superhero: The Six Step Progression,” Coogan in Superhero: The Secret Origins of a Genre, and Reynolds in Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology. Wicked warps The Wonderful Wizard of Oz into a superhero story. Elphaba’s powers, origins, dual identities, mission, and outsider status all mark her as a bona fide superhero, in the same hallowed ranks as Superman and Zorro.

Blythe and Sweet, Coogan, and Reynolds all agree that “a superhero by definition has super powers” (Blythe and Sweet). Elphaba meets this essential requirement, possessing powers on par with Hugo Danner, Superman, and Zorro. She is born with the ability to read the Grimmerie, “The Ancient Book of Thamaturgy and Enchantments” with ease, while her sorcery tutor, Madame Morrible, required “years of constant study” to “read a spell or two” (Schwartz 1.13). Elphaba gives herself the power of flight with a “levitation spell” on a broom shortly after she obtains the book (Schwartz 1.14). Even without the Grimmerie, Elphaba is a powerful sorceress, capable of telekinesis and mind control; Morrible recognizes Elphaba’s unusual powers: “Many years I’ve waited for a gift like yours to appear” (Wicked,Schwartz 1.2). Blythe and Sweet also stipulate that a superhero’s powers must be “limited” to allow a “possibility for conflict” (Blythe and Sweet). Hugo Danner, a superhuman, may have “inklings of invulnerability,” but can be killed “by the largest shells” (Wylie 20, 77). Superman has nearly identical powers to Hugo, but can be disabled by an electric shock and “can’t survive fire” (Siegel 192). Zorro is a master swordsman and clever freedom fighter, but he is mortal and can be killed like any normal man (Niblo). Elphaba discovers her limitations too, finding that her “spells are irreversible,” making her unable to reverse her spell that painfully implanted wings in Chistery’s shoulders (Schwartz 1.13). When she first discovers her powers, she claims she is “unlimited,” but later, she revises her tune, saying: “Just look at me—I’m limited” (Schwartz 1.2, 2.8). Like other superheroes, Elphaba has limited powers that elevate her above the common man.

Elphaba’s origins—her acquisition of powers and her upbringing—draw heavily from standard plot elements present in Gladiator, Superman Chronicles, and Zorro. Elphaba’s father gives her mother a “drink of green elixir” before their sexual encounter. Neither of her parents shares her unusual pigment or her powers, so the beverage is the implied source of her abilities (Schwartz 1.1). In a virtually identical scene, Hugo obtains his powers from a serum of “alkaline radicals” injected into his mother after his father, Abednego, drugs her with “opiate” in “a bottle of blackberry cordial” (Wylie 3, 9). Reynolds discusses upbringing in his definition, stating that the hero “often reaches maturity without having a relationship with his parents” (16). Elphaba’s father is the Wizard of Oz, but her mother is married to the Governor of Munchkinland (Schwartz 2.14, 1.2). Because of this, Elphaba never knows her true father, and is raised by her stepfather. Superman is also brought up by foster parents, since his biological parents die on “the doomed planet” of Krypton (Siegel 195). His foster parents die before he takes on his superheroic cause, leaving him without parents when he reaches adulthood (Siegel 196). Elphaba’s mother dies giving birth to her younger sister, Nessarose, and she has no relationship with her stepfather, who blames her for her mother’s death, openly despises her, and only sent her to school to look after her sister: “Elphaba, take care of your sister. And try not to talk so much” (Schwartz 1.7,2). Similarly, Zorro’s father ridicules his apparently weak, idiotic son, unaware that Diego Vega is Zorro (Niblo). Hugo is a “foreign person” to his father, and they never become friends; even trying “to open a conversation” with his father is a hopeless cause (Wylie 20, 121). All three characters deal with an absent father figure. The way Elphaba obtains her powers and her lack of good parenting show similarities to other superhero narratives, demonstrating that her origins fall within the well-established tropes of the genre.

All three definitions agree that a superhero must have a dual identity, an “everyday persona” coupled with a “superpowered self” (Blythe and Sweet). Reynolds states that the “extraordinary nature of the hero will be contrasted with the mundane nature of the alter ego” (16). Elphaba assumes the identity of the Wicked Witch of the West, much like Diego Vega becomes Zorro and Clark Kent becomes Superman. Coogan claims that a superhero identity “comprises the codename and the costume,” with the codename representing the hero’s “inner character” and the costume being an “iconic representation” of that inner character (32, 33). As an example, Coogan argues that Superman’s codename identifies him as “a super man who represents the best humanity can hope to achieve” and his costume emblazons the first letter of his codename on his chest (33). Elphaba adopts a superhero identity described by Madame Morrible: “Her green skin is but an outward manifestorium of her twisted nature! This distortion! This repulsion! This Wicked Witch!” (Schwartz 1.14). Elphaba’s codename fits her, because her primary power is sorcery, and “she is evil” in the eyes of the people of Oz (Schwartz 1.14). The language Morrible uses in reference to Elphaba’s “unnaturally green” skin is almost identical to Coogan’s description of the superhero costume: her skin represents the power and supposed evil inside her (Schwartz 1.1). She loses her glasses when she becomes the Wicked Witch, much like Clark Kent puts them away when he dons his Superman attire (Schwartz, Siegel). However, unlike Superman and Zorro, Elphaba does not switch back and forth between her identities. She permanently transforms into her superhero identity at the end of the first act, saying: “Something has changed within me” (Schwartz 1.14). Elphaba has the superhero’s dual identities, and her codename and costume match Coogan’s idea that they are outward manifestations of inward character.

Elphaba transforms into the Wicked Witch to accomplish a superheroic mission identical in principle to those of Superman and Zorro. Coogan argues that “the superhero’s mission is prosocial and selfless” (31). Hugo Danner’s mission is not prosocial and selfless, and Coogan notes he “gains personally from his powers,” but Elphaba, Superman, and Zorro all fit Coogan’s idea of the hero working for society’s benefit (31). Elphaba recognizes that “something bad is happening to the animals” as they are being stripped of their rights to speak (Schwartz 1.4). Though she is not an animal, she pursues justice for them when she meets the Wizard. She opens her case to the Wizard by saying, “We’re not just here for ourselves,” showing her altruistic motivations (Schwartz 1.13). She adopts her identity to fight the Wizard, who enforces the “reporting of subversive Animal activity,” once she realizes he will not defend them and that she must (Schwartz 1.14). Most of her heroic actions occur off stage, but in a conversation with Elphaba, Nessarose reports: “You [Elphaba] fly around Oz, trying to rescue animals you’ve never even met” (Schwartz 2.2). She performs superheroic deeds on stage as well. She uses a spell to give crippled Nessarose the ability to walk, she saves Boq from death by turning him into a tin man, and frees flying monkeys held captive by the Wizard (Schwartz 2.2,3). Elphaba could fit the description pinned to both Zorro and Superman–a “champion of the oppressed” (Niblo, Siegel 196). Zorro states that he fights for “justice for all,” and says, “to rid our country of a menace is a noble deed”, clearly identifying his driving motivations (Niblo). Similarly, Superman uses his powers in a “one-man battle against evil and injustice” (Siegel 84). Elphaba’s mission is exactly the same, fighting the injustice in Oz, serving as a champion of the oppressed animals.

The superhero’s mission makes them an outsider, viewed as evil by the general populace because “the superhero transgresses man’s petty laws” (Blythe and Sweet). Reynolds states that “the hero is marked out from society” (16). They often fight the establishment, because “the hero’s devotion to justice overrides even his devotion to the law” (Reynolds 16). Superman is called “the devil himself,” Zorro is called a “graveyard ghost,” and Elphaba is called “the wickedest witch there ever was” and “the enemy of all of us here in Oz” (Siegel 11, Niblo, Schwartz 1.1). Superman works above the law. His most drastic vigilante action involves reducing a ghetto to “desolate shambles” so that its reconstruction will guarantee “splendid housing conditions” (Siegel 110). From then on, police seek to “apprehend Superman” (Siegel 110). Zorro fights the government which is oppressing the poor, and a contingent of governor’s troops set out to capture him (Niblo). Elphaba first attempts to work within the law, appealing to the Wizard on behalf of the animals (Schwartz 1.13). When the Wizard refuses to comply, she says, “I’m through with playing by the rules of someone else’s game,” and becomes the Wicked Witch, a vigilante fighting for the animals and defying the Wizard, the ruling authority in Oz (Schwartz 1.14). She is outcast because society views her deeds as an evil: “Wickedness must be punished. Kill the witch!” (Schwartz 2.7). Elphaba’s defiance of law and order makes her an outsider who is hunted and viewed as wicked, much like Superman and Zorro.

Elphaba’s superpowers, origins, dual identities, altruistic mission, and outsider status all fit the well-established tropes of the superhero genre. Though the musical is not advertised as a superhero story, it contains all the necessary ingredients for one. Elphaba meets the superhero definitions of Blythe and Sweet, Reynold, and Coogan. She also draws story elements from Gladiator, Superman, and Zorro. Elphaba’s mission ends when she sees Glinda the Good send the Wizard away; with Glinda’s rule, the animals will no longer be oppressed. Her mission accomplished, Elphaba leaves Oz with her love Fiyero, akin to Zorro’s retirement and marriage to Lolita once he causes the governor to abdicate (Schwartz 2.9, Niblo). While the musical ends with Elphaba and Fiyero walking off into the night, it is not entirely implausible to imagine her coming to Earth and teaming up with this world’s mightiest heroes. The Wicked Witch of the West could be the next member of the Avengers or the Justice League; with all her similarities to those supermen, she would fit right in.

Works Cited

Blythe, Hal, and Charlie Sweet. “Superhero: The Six Step Progression.” The Hero In Transition. Bowling Green: Popular, 1983. Print.

Coogan, Peter. Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre. Austin: MonkeyBrain Books, 2006. Print.

Reynolds, Richard. Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1992. Print.

Schwartz, Steven. Wicked: The Untold Story of the Witches of Oz. 2003. Web. <http://wickedthemusicalscript.blogspot.com/>.

Siegel, Jerry and Joe Shuster. Superman Chronicles. V1. New York: DC, 2006, Print.

The Mark of Zorro. Fred Niblo. United Artists, 1920. Film.

Wicked: The Untold Story of the Witches of Oz. By Stephen Schwartz. Dir. Joe Mantello. Altria Theater, Richmond. 2 May 2014. Performance.

Wylie, Philip. Gladiator. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1930. Print.

(Joy Putney is an engineering and biology major at Washington and Lee University. When she’s not doing mad science, she loves writing fantasy novels, playing the oboe, and fighting crime.?)