First time I lost a tooth, I ran to the top of the steps and yelled, “My tooth came out!” I couldn’t see my mother in our laundry room, but she performed a reasonably convincing shout of excitement, ending with: “Looks like someone’s getting a visit from the tooth fairy tonight!”

My five-year-old body went rigid. Blood drained from my face. Tooth fairy? Who the hell was the tooth fairy?

I must have a gothic disposition, because I assumed this creature would be coming for the rest of my still-attached teeth. One of Poe’s narrators does that, plucks out his beloved’s beautiful incisors and bicuspids with a pair of pliers. But Germany’s E. T. A. Hoffman is the better source for inverted fairies. A student in my English Capstone assigned the 1816 “Der Sandmann” to our class earlier this semester. Hoffman takes the harmless Sandman, bringer of sleep to dozy children, and twists him into “a wicked man” who “throws handfuls of sand into their eyes, so that they jump out of their heads all bloody; and he puts them into a bag and takes them to the half-moon as food for his little ones.”

That’s the guy Metallica is singing about. Although the Hans Anderson version isn’t all goodnight kisses either. Ole-Luk-Oie, the Dream-God, may be very “fond of children,” but if you’ve been naughty, he holds a black umbrella over you all night so come morning you’ve dreamt nothing at all. His sibling is named Ole-Luk-Oie too, except “he never visits anyone but once, and when he does come, he takes him away on his horse, and tells him stories as they ride along. He knows only two. One of these is so wonderfully beautiful, that no one in the world can imagine anything like it; but the other is just as ugly and frightful, so that it would be impossible to describe it.” The other Sandman isn’t a Dream-God. He’s Death.

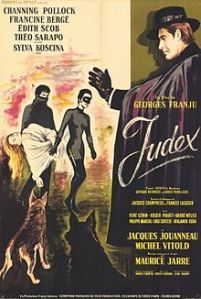

I prefer Hoffman’s eye-plucking fairy. He reveals “the path of the wonderful and adventurous” as the child-narrator tries to unmask him. That’s right, “the terrible Sand-man” is a dual-identity supervillain. The kid recognizes his father’s business partner, a literally Satanic lawyer who practices alchemy by night. If the Faust allusions aren’t clear, then note his “sepulchral voice” and the laboratory explosion that kills the hapless dad. Hoffman even quotes Goethe after strumming the ubermench theme song: “Father treated him as if he were a being from a higher race.”

Enter Golden Age comic writer Gardner Fox. He must have spent a lot of time under Ole-Luk-Oie’s other umbrella, the one with the pictures twirling on the inside. He dreamt up the Flash, Hawkman, Dr. Fate and the Justice Society of America. Bill Finger usually gets credit as Batman’s original writer, but Fox wrote six of the first eight episodes, each almost twice as long as Finger’s introductory 6-pagers. Instead of apprehending jewel thieves and serial killers, Fox’s phantasmagoric Dark Knight faces down a werewolf-vampire and some guy who steals faces and puts them on talking flowers.

When Finger returned Batman to the grit of crime alley in 1940, Fox dreamt up the Sandman, your standard fedora-wearing Mystery Man, except in a World War I gas mask. He stole his knock-out pellets from Batman’s utility belt (a Fox invention), though they’d already been field-tested by Johnston McCulley’s Bat and WXYZ’s Green Hornet. When Jack Kirby and Joe Simon got tired of spinning Timely’s umbrella of characters, they traded in the Sandman’s business suit for a red and yellow leotard and a sidekick named Sandy. They kept the color scheme when they revised him again in 1974, this time as the Sandman of Hans Anderson lore, a protector of children’s dreams. That’s the dopey series Neil Gaiman reawakened in 1988.

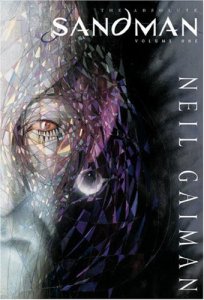

I was too busy mourning the collapse of Alan Moore’s short-lived Mad Love company to take adequate notice at the time. Gaiman stripped off the leotard, but I still considered his white-skinned Morpheus just another superhero reboot. I thought the future of comics was Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz’s Big Numbers and Dave McKean’s Cages. I was wrong. McKean’s publisher Tundra died almost as fast as Mad Love. I’m sure he made better money painting Sandman covers anyway.

Sandman is easily the best-selling and best-regarded comic of the 90s. When I attended a comics forum last month, it was the only work to receive its own three-scholar panel. Unfortunately the forum was in Michigan after a bout of “snow thunder” had reduced the state to a lake of frozen slush, and none of the three panelists showed up. Maybe the empty podium was their way of evoking a night spent under the Sandman’s black umbrella.

I prefer Gaiman’s non-graphic novels anyway. Stardust was one of the last books I read aloud to my kids, my wife regularly teaches American Gods, and Coraline once shattered an MFA-induced writing block of mine, not just its twirling dreamscape, but the deceptively Stein-esque simplicity of its sentences. This also lea\d to a parenting low point when my wife and I refused to leave a matinee of the film adaptation even though our son was trying to claw over the back of his seat to escape. And yet the emotional scars did not prevent him from later writing a book report on Neverwhere. He likes Good Omens too.

Like Hans Anderson, DC spun-off the Sandman’s sibling Death, but when Gaiman killed Sandman, his contract stipulated that it would stay dead. Because, as Ole-Luk-Oie warns his listeners, “You may have too much of a good thing.” I was paying enough attention to buy that 75th and final issue, a riff on Shakespeare’s Tempest. It turns out the bard is a bit of a Faust himself. The talentless hack accepts a contract as the Sandman’s front man, inundating the world with dream stuff for centuries to come. “There is nobody in the world,” wrote Hans, “who knows so many stories as Ole-Luk-Oie, or who can relate them so nicely.”