I start a new course this spring term, “Making Comics,” a creative writing and studio arts hybrid I am team-teaching with Leigh Ann Beavers of W&L’s Art department. For my half of the four weeks, our students are writing comic book scripts–which they’ll then turn into actual physical comic books in the second half.

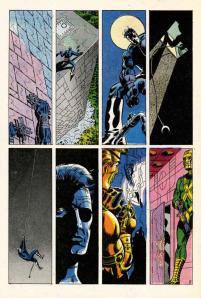

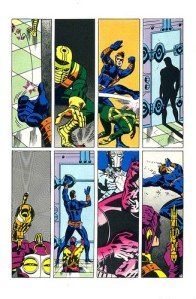

I’ve studied comics but never written one, so I spent a lot my winter term experimenting in the form. It’s not as easy as it looks. Our students will be crafting 14-page books, but I assigned myself several 22-page scripts (a common but not universal standard for an individual issues of a series published by a U.S. comics publisher). I’m using Dark Horse Comics’ preferred format (downloadable here), but break with industry norms by designing layout too–something writers are expected to leave to artists. But if you’re not thinking about layout, and so about panels’ shapes, sizes, framing, and relationships, then you’re not really thinking about a comic book as a form. To write “Double Trouble,” I conceptualized layouts that would work intrinsically with the story, and I also thought a lot about the peculiar nature of time and space in comics, and the odd relationships between words and images and how they can overlap and double in meaning.

Two stories unfold simultaneously. In the left column, Mina and her friends drive to a remote mountain cabin to spend a night partying in the woods (yes, a hackneyed genre, but stay tuned). In the right column, Mina’s twin sister Gemma returns to the cabin months later to investigate the deaths of her friends. But the two also flow back and forth across the page as the sisters foreshadow and relive the same moments. Or at least that’s how things start out. The relationship between the “sisters” gets a lot more complicated, which scrambles the layout too.

So here goes . . .

Double Trouble: Prequel-Sequel, Issue 1

COVER

A scenic mountain forest with a female figure standing with her back to us. The image is divided into eight equal horizontal panels. The left column of four panels features Mina in bikini top, summer shorts, and sandals, with the trees in full bloom and a bright afternoon sky. The right column of four panels features Gemma in light jacket, jeans and hiking boots, with skeletal tree branches and an overcast evening sky. The center gutter divides the mirrored figure of Mina-Gemma down the center of her back. She holds an identical knife in each hand.

PAGE ONE (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. Mina sits at the dressing table in her bedroom, looking at us and the implied mirror. She is wearing a light nightgown and a light robe. She has just picked up her phone with her right hand, and she holds a make-up eyeliner in her other hand. All of the make-up is jumbled on one side of the table, with the opposite side bare. A male figure sleeps in the bed behind her in the right half of the panel.

MINA:

Oh hi, Gemma.

Panel 1b. Gemma, who is identical to Mina, sits at a bare table in a police interrogation room, looking at us and an implied police officer. She is wearing an orange prison jumpsuit and is handcuffed to the table.

CAP (Mina):

“No, I’m staying in this weekend. How about you?”

Panel 2b. Same framing as 1a, Mina leans forward as she applies the eyeliner.

MINA:

Oh, you know about the camping trip, huh?

Panel 2b. Gemma sits at a defendant’s table in a courtroom, looking at us and the implied judge. She is wearing a conservative suit. Her roots have grown in dark. Her attorney sits beside her in the right of the frame, mostly cropped.

JUDGE (off-panel):

You are free to go.

3a. Same framing as 1a, Mina has put down the eyeliner and picked up a make-up brush.

MINA:

I mean if you really want to.

Panel 3b. Gemma sits on a couch in a psychiatrist office, facing us and the implied psychiatrist. A framed diploma and clock on the wall, psychology texts on the bookshelf, and a box of tissues on the coffee suggest the location. She is dressed up but not as excessively as she was for court. Her hair has grown about two inches since 1b.

PSYCHIATRIST (off-panel):

But in my professional psychiatric opinion . . .

Panel 4a. Same framing as 1a, Mina leans forward again to apply more make-up.

MINA:

I just don’t think you’ll have a good time.

Panel 4b. The bedroom and framing of 1a-4a, but in dimmer light. Gemma has just entered the room and is standing between the bed and the dressing table. She’s in the casual autumnal clothes as seen on the COVER. Her hair is about three inches longer than in 1b. Her head is turned toward the dressing table and us. The jumble of make-up is the same.

CAP (Psychiatrist):

“It’s too soon to go back.”

PAGE TWO (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. In the bedroom, the framing has shifted forward to the boyfriend in the bed, so that Mina is mostly cropped in the left edge of the panel. The boyfriend, Jerry, is sitting up in the sheets, shirtless, talking to her back.

JERRY:

Was that your sister? She’s not coming is she?

Panel 1b. Similar framing, but the bed is an autopsy table, and Jerry’s corpse has been cut open by the medical examiners standing over him conducting the autopsy.

CAP (Jerry):

“I know it’s a messy situation and all, but let’s be open.”

Panel 2a. Same framing as 1a, but Gemma has stood up, dropping her bathrobe to her elbows, her back still to Jerry.

JERRY:

Things are a hell of a lot more fun when she’s not around.

Panel 2b. Jerry’s naked body now lies on a mortician’s table as morticians clean and sew him up.

CAP (Jerry):

“Gemma is so high maintenance.”

3a. Same framing as 1a, Gemma has turned around and is approaching the bed, her back to us, and the robe dangling from her right hand.

JERRY:

Not like you, Mina.

Panel 3b. Jerry’s made-up and well-dressed body lies in an open casket, as mourners move around it.

CAP (Jerry):

“You’re the life of the party.”

Panel 4a. Closer on Jerry in bed, the sheets barely covering him. He is talking directly to us and so to Mina who is now out of frame.

JERRY:

Now why don’t you climb in here with me and we have some fun right now?

Panel 4b. Gemma stands before Jerry’s funeral plot, her back to us. The mound in front of the tombstone has begun to flatten and sprout new grass. The plot is angled and framed to parallel the bed in 1a-3a.

PAGE THREE (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. In Mina’s plush bathroom, she is newly showered, with a towel tied around her torso and another around her hair. She has a toiletry bag in one hand and her phone in the other. She is stepping into the bathroom from the bedroom, while talking to a friend on speaker.

PHONE:

Is this going to be like totally roughing it? No shower, piss in the woods, that kinda deal?

Panel 1b. Gemma continues Mina’s progression forward to the now visible sink, where she is reaching to open the medicine cabinet.

CAP: “It was my parents’ secret getaway. It has everything but a bidet.”

Panel 2a. Same framing as 1b, Mina is reaching into the now open medicine cabinet and dropping toiletries into the toiletry bag on the sink counter with one hand. Her other hand is about to grab a prescription bottle from the shelf. The phone is resting on the counter.

PHONE:

What are you packing?

Panel 2b. From Gemma’s perspective, close on the prescription bottle in her hand. It contains “Risperidone” and is filled out to “Gemma Pollock.” She is about to twist the cap off with her other hand.

CAP:

“Oh, just a few necessities. How about you?”

3a. From Mina’s perspective, close on the inside of the bottle and the few pills at the bottom.

PHONE:

Are you kidding? My suitcase is a bottomless pit.

Panel 3b. Gemma is placing the re-capped bottle into her jacket pocket.

CAP:

“Hey, it never hurts to be prepared.”

Panel 4a. Mina drops the bottle into her toiletry bag with one hand and begins to close the medicine cabinet with the other.

MINA:

Like my mother used to tell me . . .

Panel 4b. From Gemma’s perspective, she has just closed the medicine cabinet and now is staring at her own reflection. Her fingers are on the bottom of the mirror.

CAP:

“. . . always put your best self forward.”

PAGE FOUR (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. Front yard and walkway of Mina’s suburban house. She, Jerry, and four friends are dressed in summer clothes and are exiting the house and walking down the walkway which is angled diagonally through the panel. One of the friends is cropped by the right gutter. They are carrying coolers and other weekend supplies. It’s a bright early summer morning.

FRIEND 1:

Looks like we’re heading into a perfect day.

FRIEND 2:

We all going to fit in one car?

Panel 1b. Continuous with 1a, the walkway ends at the street where Gemma’s car is parked. Gemma is approaching the car alone. It’s an overcast autumn afternoon.

CAP:

“The more the merrier.”

Panel 2a. The back half of the car viewed from the side, the trunk and side doors are open as the friends load up and pile in. The gutter divides the car at its center.

FRIEND 3:

Damn! How much beer did you pack?

FRIEND 4:

I call shotgun!

Panel 2b. Continuous with 2a, the front half of the car, Gemma is driving alone, facing toward the right edge of the panel. The car is in motion, the background of houses blurred.

CAP (Jerry):

“Sure you don’t want me to drive, hon?”

Panel 3a. Left half of the car as seen through the windshield, the car is in motion and the friends are having rambunctious fun as they ride. One has her head out of the passenger window, her hair blowing back. Jerry is seated in the middle of the front seat and is cropped roughly in half by the gutter.

FRIEND 1:

I love this song!

FRIEND 3:

Turn it up!

Panel 3b. Continuous with 3a, the right half of car as seen through the windshield, the car is stopped. Gemma is getting gas and has the nozzle raised and the gas cap off.

CAP:

“No stop signs! Speed limit! Nobody’s gonna slow me down!”

Panel 4a. Close on Mina at the wheel, facing us and laughing and singing as she drives.

SFX:

I’m on the way to the promised land!

Panel 4b. Gemma’s distant car is climbing the highway into foreboding mountains.

PAGE FIVE (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. At the cabin clearing, the car is parked at an angle, its right front corner out of frame. The doors and trunk are open as the friends jump out. The cabin is in front of them, with trees and blue sky beyond it.

FRIEND 2:

It’s a dream up here.

MINA:

Welcome to paradise!

FRIEND 4:

I can’t believe how pristine it is.

Panel 1b. Continuous with 1a, the cabin is centered in the gutter, with skeletal trees and moon-lit sky beyond it. The front right corner of the car shines its headlights across the clearing and the right half of the cabin’s porch, which is blocked by heavily worn police tape. Gemma has stepped out of the car is approaching the porch with a lit flashlight.

CAP:

“It’s like we stepped out of time.”

Panel 2a. The framing moves forward, cropping the car out of the panel and expanding the cabin. The cabin door is open and half-cropped in the right of the panel. The friends are entering with the supplies.

JERRY:

This is really all yours?

MINA:

Hell yeah.

Panel 2b. Continuous with 2a, the porch and door are centered in the gutter. The window is boarded, but the door has been removed from its hinges and leans sideways under the wall. Gemma has stepped onto the porch from the right side of the panel, flashlight shining. She has broken some of the police tape which now dangles.

CAP:

“My family values privacy.”

Panel 3a. Inside the cabin, the friends are unpacking in the kitchen as Mina and Jerry are moving through the living room in the foreground. Mina is carrying a backpack in one hand and leading Jerry with the other.

FRIEND 3:

Look at this place.

FRIEND 1:

We could live up here forever.

Panel 3b. Continuous with 3a, Gemma is standing in the doorway with the flashlight. The doorway is to the right of the kitchen.

CAP:

“No one would ever find us.”

Panel 4a. Mina and Jerry have continued down the hallway and are entering a bedroom door on the left edge of the panel.

FRIEND (off-panel):

How many bedrooms are there?

MINA:

This way, Jerry.

Panel 4b. Continuous with 4a, Gemma is in the empty and ruined kitchen, looking toward the hallway.

CAP:

“You get the private tour.”

PAGE SIX (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. Framed by the door frame, Mina and Jerry standing kissing in the middle of the bedroom. Her backpack is now on the bed.

Panel 1b. Same framing as 4a of previous page, Gemma is standing in the hallway, looking through the bedroom door at the right edge of the panel.

Panel 2a. Same framing as 1a, Mina pulls away from Jerry’s embrace as she looks down at the trapdoor at their feet.

MINA:

What’s that?

Panel 2b. Same framing as 2a, the trapdoor is raised, and Gemma is shining her flashlight down through the opening. The bedroom furniture is the same but disarranged.

CAP (Mina):

“Oh my god, where do you think it goes?”

Panel 3a. Framed by the trapdoor opening, looking up from the basement, Jerry is looking down at us and unseen Mina who has already descended out of frame.

JERRY:

Is this really a good idea?

Panel 3b. Viewed from above, Gemma is stepping down onto the basement floor, while giving a last look up at us.

CAP (Mina):

“God. You sound like my sister.”

Panel 4a. Mina in the basement pulls on a light string, with the ladder directly behind her. A bare bulb illuminates the space.

JERRY (off-panel):

Why don’t you come on back up now?

Panel 4b. Continuous with 4a, Gemma has continued forward from Mina’s position, the flashlight shining into the right side of the panel. A large male figure stands silhouetted behind her and partly cropped by the middle gutter.

CAP (Mina):

Why? There’s nothing even down here.

PAGE SEVEN (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. With the ladder and light cord behind her, Mina in profile has stepped further into the basement. She is squinting uncertainly toward the next panel.

MINA (whisper):

Gemma?

Panel 1b. Continuous space from 1a, Gemma is turning as if in response to Mina. A pair of storm doors are propped open in the background in the right half of the panel, trees and sky visible outside.

CAP (Mina):

“What the hell are you doing here?”

Panel 2a. Same framing as 1a, Mina has stepped into the right half of the panel, closer to Gemma’s panel.

MINA:

You can’t just barge in anytime you like.

Panel 2b. Same framing as 1b, Gemma has fully turned and is shining the flashlight beam toward Mina’s panel.

CAP (Mina):

“I know, you’re just trying to keep an eye on me, but this is crazy.”

Panel 3a. The framing moves with Mina as she steps further forward toward panel 3b, leaving the ladder out of frame but the cord still behind her. The edge of the storm doors is just visible in front of her.

MINA:

And I already know you think going off the meds was a bad idea.

Panel 3b. The framing moves with Gemma as she steps forward toward panel 3a, with the cord dangling in front of her and the storm doors now out of frame.

CAP (Mina):

“Especially right after mom and dad’s funeral.”

Panel 4a. Mina is now standing where Gemma was originally, still speaking as if to Gemma’s figure facing her in panel 4b. Behind her a large male arm is about to grab her right shoulder. The arm is bare.

MINA:

But I have to move forward in my own direction.

Panel 4b. Gemma is now standing where Mina was originally, with the ladder and light cord in the left half of the frame, as she continues to look toward Mina in panel 4a. Behind her a large male arm is about to grab her left shoulder. The arm is clothed in a coat sleeve.

CAP (Mina):

“I don’t want to be you. And I’m not going to let you pull me back.”

PAGE EIGHT (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. Mina, who is in the right half of the panel, is spinning around to see Jerry standing behind her facing us, with the ladder behind him.

JERRY:

Sorry!

Panel 1b. Gemma, who is in the left half of the panel, has spun around to see a park ranger behind facing us, with the storm door behind him.

RANGER:

Didn’t mean to scare you, miss.

Panel 2a. Jerry is taking Mina’s arm.

JERRY:

Why are we even down here? It smells like something died.

Panel 2b. The ranger has taken Gemma’s arm and is gesturing toward the storm doors with his other hand.

RANGER:

It’s not safe. I’m going to have to escort you off the premises.

Panel 3a. Mina is yanking her arm away.

MINA:

You really are like Gemma! Why’s everybody always bossing me around?

Panel 3b. Gemma has yanked her arm away.

GEMMA:

This is my property. I inherited it from my parents. You’re the one trespassing.

Panel 4a. Mina has stepped past Jerry to the ladder.

JERRY:

Okay, okay, it’s yours, I get it. Who were you talking to anyway?

CAP (Ranger):

“Gemma Pollock?”

Panel 4b. Gemma has stepped past the ranger to the storm door steps.

CAP (Jerry):

“It was Gemma, wasn’t it?”

RANGER:

You’re Gemma Pollock?

PAGE NINE (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. Mina is climbing the ladder, her back to us and Jerry.

MINA:

That’s not like a crime you know. She’s still a part of my life.

Panel 1b. Gemma is walking up the storm door steps, her back to us and the ranger.

RANGER:

I know, I just never imagined you of all people would want to come back here.

Panel 2a. Pullback from 1a to show a silhouetted female figure holding a knife in her left hand and watching as Jerry follows Mina up the ladder.

CAP (Gemma):

“I’m looking for someone.”

JERRY:

I thought you were trying to forget her. Isn’t that the whole point of this trip?

Panel 2b. Pullback to show a silhouetted female figure holding a knife in her right hand and watching as the ranger follows Gemma up the steps.

CAP (Mina):

“It’s not like I can control when she pops up.”

RANGER:

You mean the remains? The news said one of the bodies was never found.

Panel 3a. Viewed down from the top of the ladder as Jerry is stepping out of frame, the female figure in the basement is moving toward the base of the ladder.

JERRY:

I say live in the present.

Panel 3b. Viewed from the top of the steps as the ranger is stepping out of frame, the figure is moving toward the bottom of the steps.

GEMMA:

The D.A. threatened life without parole trying to get me to say where I hid it.

Panel 4a. Mina’s hand begins to push the trapdoor closed behind her, blocking some of the figure as the door starts to fall.

JERRY:

And keep the past in the past.

CAP (Ranger):

“But you were acquitted.”

Panel 4b. Gemma’s hand withdraws as the storm door slams shut behind her.

SFX:

Slam

GEMMA (head off-panel):

And the case closed.

PAGE TEN (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. The four friends are on the porch drinking.

CAP (Ranger):

“There must be a lot of painful memories here for you.”

Panel 1b. Continuous panels, Gemma is walking along the side of the cabin toward the ranger’s parked car. The ranger is following behind her.

GEMMA:

They follow me wherever I go.

Panel 2a. Jerry is in the bedroom doorway, gesturing down the hallway. Mina is sitting on the bed.

JERRY:

Sounds like they started without us.

MINA:

Go ahead. I’m tired. I’m going to lie down for a minute.

Panel 2b. Mina is stepping onto the porch as the ranger turns around at his car.

RANGER:

Wait. You’re sleeping here? Alone?

CAP (Jerry):

“Want some help warming up that bed?”

Panel 3a. Similar framing of porch as 2b, the friends are getting rowdier as they drink.

CAP (Gemma):

“I prefer my privacy.”

Panel 3b. Gemma has stepped into the cabin and is beginning to shut the door.

GEMMA:

Goodnight.

CAP (Mina):

“I’ll be out later.”

Panel 4a. Same framing as 3b, Jerry is stepping out to the porch to join the drunken friends.

CAP (Ranger):

“I’ll come back in the morning to check on you.”

CAP (Gemma):

“Just don’t wake me up. I’m a late sleeper.”

Panel 4b. Close on living room window visible in 3b, but now broken with half of the glass missing. Gemma stands looking out, as the ranger’s car is reflected in the bottom of the glass as it drives away.

CAP (Jerry):

“Whatever you say, hon.”

PAGE ELEVEN (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. Mina sits alone on her bed, the room expansive around her. Her backpack lies on the bed. The door is closed.

Panel 1b. Same framing as 1a, Gemma stands in the open doorway.

Panel 2a. Closer on Mina, she has pulled the backpack to her and is reaching inside it.

Panel 2b. Closer on Gemma, she is holding her jacket open with one hand and has just pulled out the prescription bottle with her other hand.

Panel 3a. Mina throws her head back to swallow the contents of the bottle. The cap is in her other hand.

Panel 3b. Gemma holds the bottle upside down, as the spilled pills click against the floor.

SFX:

Click click click

Panel 4a. Looking down at her, Mina lies back on the bed, looking up at us and the ceiling.

Panel 4b. Same framing of the bed, Gemma lies back on the bed, but her eyes have just closed. Because the bed is not in the same position as in 4a, the walls and the corner of the trapdoor on the floor appear crooked.

PAGE TWELVE (eight vertical panels, two rows of four)

Panel 1a. Gemma stands looking down at Mina in bed, while holding a knife in her right hand.

GEMMA:

Mina?

Panel 1b. Viewed from above, Mina’s hand reaches over to wake Gemma. The rest of Mina is cropped.

Panel 2a. Continuous with 1b, after the gutter Gemma in her bed becomes Mina in hers, with Gemma’s hand reaching over to wake Mina from the other side of the bed. The bed is centered in the middle gutter. The rest of Gemma is cropped.

MINA & GEMMA (heads off-panel, centered in middle gutter):

Are you awake?

Panel 2b. A mirror of 1a, Mina stands looking down at Gemma in bed, while holding a knife in her left hand.

MINA:

Gemma?

Panel 3a. Similar framing as 1a, Mina jerks upright in bed, looking to the left edge of the panel where Gemma is no longer standing.

MINA:

Gemma?

Panel 3b. Similar framing as 1b, Gemma jerks upright in bed, looking to the right edge of the panel where Mina is no longer standing. The bed appears continuous with the bed in 3a. Their bodies do not overlap at all.

GEMMA:

Mina?

Panel 4a. Same framing as 3a, Mina turns to look at Gemma across the gutter to the right.

MINA & GEMMA (centered in gutter)

Am I awake?

Panel 4b. Same framing as 3b, Gemma turns to look at Mina across the gutter to the left.

PAGE THIRTEEN (eight vertical panels, two rows of four)

Panels 1a and 1b. Same framing as previous panels, but now Gemma’s hand reaches across the gutter to touch Mina, and Mina’s hand reaches across the gutter to touch Gemma.

Panels 2a and 2b. Same framing as 1a and 2a, Mina and Gemma are holding hands across the gutter as they move forward to climb off the bed and leave. Mina’s left hand holds Gemma’s right hand.

MINA (in 2a) & GEMMA (in 2b) (centered in gutter):

Come on. I have to show you something.

Panels 3a and 3b. Outside, still holding hands across the gutter, Mina and Gemma walk toward us, away from the cabin, which is behind them.

MINA (in 3a) & GEMMA (in 3b) (centered in gutter):

Where are we going?

Panels 4a and 4b. Still holding hands across the gutter, Mina and Gemma walk away from us and into the forest of birch trees. Because we are viewing their backs now, Mina’s right hand holds Gemma’s left hand.

MINA (in 4a) & GEMMA (in 4b) (centered in gutter):

Trust me.

PAGE FOURTEEN (eight vertical panels, two rows of four)

Panels 1a and 1b. On a path ending at a ledge overlooking a waterfall, Mina stays a step behind in 1a, as Gemma moves onto the ledge in 1b. The waterfall is in front of Gemma and to her side and is centered in the middle gutter.

MINA (in 1a):

Yes and no.

GEMMA (in 1b) and MINA (in 2a) (centered in middle gutter):

Have I been here before?

Panels 2a and 2b. A mirror of 1a and 1b, Mina is on the ledge, and Gemma is behind her.

GEMMA (in 2b):

Yes and no.

Panels 3a and 3b. Same framing as 1a and 1b, though the water pouring down from 1b into 3a appears continuous. Mina shoves Gemma off the ledge with one hand. She holds a knife in her other hand.

MINA (in 3a):

I’m sorry, Gemma.

GEMMA (in 3b):

Mina!

Panels 4a and 4b. Same framing as 2a and 2b, with the water pouring down continuously from 2a into 4a. Mina and Gemma mirror their figures in 3a and 3b, as Gemma shoves Mina off the ledge with one hand. She holds a knife in her other hand.

MINA (in 4a):

Gemma!

GEMMA (in 4b):

I’m sorry, Mina.

PAGE FIFTEEN (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. In Mina’s cabin bedroom with bright morning light, Gemma jerks awake in bed next to Jerry’s sleeping body. This is Mina’s bright, summery world, but Gemma, who is still dressed as Gemma, is also colored as though still in her autumnal world.

GEMMA:

No!

Panel 2b. Same framing as 1a, in Gemma’s cabin bedroom with overcast morning light, Mina just jerked awake and is looking around. This is Gemma’s dim, autumnal world, but Mina, who is still dressed as Mina, is also colored as though still in her summery world.

MINA (small):

Where am I?

Panel 2a. Same framing, Gemma freezes in wide-eyed alarm as Jerry’s naked arm rises and he touches her on the back.

JERRY:

Where do you think you are? Safe in bed with me.

Panel 2b. Mina stands, alarmed by the absence of Jerry in the bed. The door is open behind her, and a male figure is silhouetted.

MINA:

Jerry?

Panel 3a. Gemma stands, alarmed by the presence of Jerry in the bed. The door is closed behind her.

GEMMA:

Where the hell did you come from?

Panel 3b. The ranger steps through the door, as Mina spins toward him.

RANGER:

I kept knocking at the front door. I was afraid you were . . .

Panel 4a. Gemma backs away from Jerry to the closed door.

GEMMA:

Dead! You’re supposed to be dead!

PAGE SIXTEEN (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. Jerry stands up and points at Gemma.

JERRY:

You’re Gemma, aren’t you? What did you do with Mina?

Panel 1b. The ranger leans away from Mina as she points at him.

RANGER:

With who?

MINA:

With Gemma! My sister! Did you kill her?

Panel 2a. Jerry leans away as Gemma points at him.

GEMMA:

I wouldn’t hurt my own sister.

Panel 2b. Mina stares at the ranger confused.

RANGER:

But you don’t have a sister.

Panel 3a. From the hallway, Gemma has shoved the door open and storms out of the bedroom, with Jerry following her.

GEMMA:

What the hell are you talking about?

SFX:

slam

JERRY:

You’re going to wake everybody up.

GEMMA:

There’s nobody else here!

Panel 3b. Mina storms down the hallway, with the ranger following her.

MINA:

Up! Wake up! Everybody up!

RANGER:

There’s nobody else here.

Panel 4a. Gemma shoves open another bedroom to find an empty bed. Clothes and suitcases are arranged as though two people slept there recently.

GEMMA:

Whose stuff is this? Where am I?

Panel 4b. Mina has entered the same bedroom, though now the items are gone and the space dilapidated.

MINA:

Where’d everybody go?

PAGE SEVENTEEN (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panel 1a. In the hallway, Gemma has turned away from the bedroom and is walking toward us and the main room. Jerry follows behind her.

GEMMA:

Oh my god. My sister. The pills. I shouldn’t have let her . . .

Panel 1b. Mina has continued down the hallway and is in the living room space now, with the ranger following behind her.

RANGER:

The pills?

MINA:

I think she did this.

Panel 2a. Gemma has spun around to face Jerry in profile. The living room is behind them.

GEMMA:

I think she killed everybody.

JERRY:

You’re not making any sense.

Panel 2b. Opposite angel as 2a, Mina has spun around to face the ranger in profile. The kitchen is behind them.

RANGER:

Why don’t you lie down?

MINA:

I have to find her!

Panel 3a. Gemma has spun away from Jerry.

GEMMA:

I can still stop this.

JERRY:

Let me get your medication.

Panel 3b. The ranger raises a beer cooler behind Mina, as Mina is about to step onto the porch.

RANGER: It’s in the bedroom, right?

MINA:

This is all my fault.

Panel 4a. Jerry strikes Gemma over the back of the head with the cooler.

GEMMA:

I never thought she would –-

Panel 4b. Mina drops to the floor in front of the rangers’ feet.

PAGE EIGHTEEN (eight mixed panels, two rows for four)

Panel 1a. A vertical panel, in the woods with summery trees in the background, Gemma is standing and looking down into the next panel.

GEMMA:

Mina, can you hear me?

Panel 1b. A vertical panel, the trees in the background are skeletal, but continuous with 1a. Mina sits on the ground, facing the left of the page, with her hands tied to the middle gutter behind her back. The gutter appears to represent a tree. Her head is rising as if she is just waking up. Her legs are cropped by the left gutter, but would otherwise extend into 1a.

MINA (weak):

Gemma?

Panel 2a. A vertical panel, a mirror of 1b, Gemma sits on the ground facing to the right of the page, with her hands tied to the middle gutter behind her back. The summery trees are continuous with panels 1a and 1b. Gemma’s head is rising.

GEMMA (weak):

Is that you?

Panel 2b. A vertical panel and mirror of 1a, Mina stands, looking down into 2a, with skeletal trees that are continuous with the trees across all four panels.

MINA:

I need you to wake up now.

Panels 3a and 3b. Vertical panels, similar framing as 1b and 2a, but from the opposite angle, so Gemma sits facing to the left with summery trees in the background, and Mina faces right with skeletal trees. Their hands are now touching in the gutter.

GEMMA:

Mina!

MINA:

Oh thank God, you’re here, Gemma!

Panel 4a. A horizontal panel in a two-panel half-column filling the bottom quarter of the page, Gemma’s legs extend the length of the panel, with her head and torso cropped, and her back to the gutter. Her hand is untying Mina’s rope in the gutter.

GEMMA (head off-panel):

It was him!

Panel 4b. A horizontal panel and mirror of 4b above it, Mina unties Gemma’s rope in the left gutter, with her legs extending to the right.

MINA (head off-panel):

I know!

PAGE NINETEEN (eight mixed panels, ambiguous reading path)

1a. A horizontal panel, Gemma is untied now and steps into the frame from the left gutter as she crouches and finishes untying Mina.

GEMMA:

Come on.

1b. A horizon panel below 1a, and a mirror of 1a, Mina steps into the frame from the right gutter and crouches as she finishes untying Gemma.

MINA:

We have to get out of here.

Panel 2a. A vertical panel beginning in the top right quarter of the page, Gemma leads Mina down the panel into the summery woods.

MINA:

Which way?

Panel 2b. A vertical panel completing the top row, Mina leads Gemma up the panel into the skeletal woods.

GEMMA:

We’re going to get lost.

Panel 3a. A horizontal panel directly below 2a, Gemma leads Mina into the summery woods.

MINA:

We’re going to get lost.

Panel 3b. A horizontal panel directly below 23a completing the column filling the left half of the page, Mina leads Gemma into the woods.

GEMMA:

Which way?

Panel 4a. A vertical panel directly below 2a, Gemma leads Mina in a continuation of both 2a and 3a.

GEMMA:

It doesn’t matter.

Panel 4b. A vertical panel directly below 2b, Mina leads Gemma into a clearing.

MINA:

We end up in the same place.

PAGE TWENTY (eight mixed panels)

Panel 1b. A horizontal panel, Mina and Gemma stop and look forward, facing us.

Panel 1a. A horizontal panel completing the top row, Mina and Gemma have stopped with their backs to us and are looking at the waterfall in front of them.

GEMMA:

We always do.

Panel 2a. A vertical panel beginning the middle row, Gemma looks over the ledge and points as Mina steps closer.

GEMMA:

Oh my god.

Panels 2b and 3a. Two horizontal panels forming a half-column in the center square of the page, four corpses of the friends are piled in the stream and rocks below. In the top panel, they are decayed skeletons; in the bottom panel, they are freshly killed.

Panel 3b. A mirror of 2a, a vertical panel completing the middle row, Mina looks over the ledge and points as Gemma steps closer.

MINA:

Look.

Panel 4b. A horizontal panel, Gemma stands looking down as the ranger appears from the woods behind her shoulder, raising a knife. Mina is gone, possibly out of frame in the left gutter.

JERRY and RANGER (centered in middle gutter):

You shouldn’t be here.

Panel 4a. A horizontal panel and mirror of 4b, Jerry appears from the woods behind Mina’s shoulder, raising a knife. Gemma is gone, possibly out of frame in the right gutter.

PAGE TWENTY-ONE (eight mixed panels, three rows)

Panel 1a. A horizontal panel, Gemma appears behind Jerry and shoves him toward the ledge as he drops the knife and Mina lunges out of the way.

GEMMA:

No!

Panel 1b. A horizontal panel and mirror of 1a, Gemma lunges out of the way as the ranger is shoved by Mina.

MINA:

No!

Panel 2b. A vertical panel, Gemma looks down into 4b directly below them, which is continuous.

Panel 2a. A vertical panel, the ranger’s cropped body twisting and falling.

Panel 3b. A vertical panel and mirror of 2a, Jerry’s cropped body twisting and falling.

Panel 3a. A vertical panel and mirror of 2b, Mina looks down into 4a directly below them, which is continuous.

Panel 4b. A horizontal panel, the ranger lies on the rocks below, his head in the left half of the panel, completing his fall diagonally from the top right of the page to the bottom left.

Panel 4a. A mirror of 4b, Jerry lies on the rocks below, his head in the right half of the panel, completing his fall diagonally from the top left of the page to the bottom right.

MINA (in panel 3a above):

Let’s get out of here.

PAGE TWENTY-TWO (eight horizontal panels, four rows, two columns)

Panels 1b and 1a. The panels are continuous. In the left autumnal panel, Gemma emerges from the woods with her back to us and enters the clearing with the cabin in front of her. In the right summery panel, Mina emerges beside her. The cabin is centered with the gutter.

CAP (in 1b):

I don’t believe in fate.

CAP (in 1a):

I don’t even believe in the past.

Panels 2b and 2a. Continuous panels, as viewed from behind the car, which is parked at an angle in front of the cabin and is divided by the gutter. In the left autumnal panel, Gemma is opening the driver’s door to climb in. In the right summery panel, Mina is climbing into the front passenger seat.

CAP (in 2b):

Why shouldn’t they change?

CAP (in 2a):

They’re both open doors.

Panels 3b and 3a. Continuous panels viewed through the windshield, Gemma sits in the passenger seat in the left panel, and Mina drives in the right panel. Their heads are partly turned to look at each other.

CAP (in 3b):

We have to find our own way home.

CAP (in 3a):

We have to steer ourselves.

Panels 4b and 4a. Continuous panels, the rocky base of the waterfall, water pours down, centered with the gutter. The angle is slightly upward. In the left panel, a skeleton hand droops palm-up over a rock, the arm and the rest of the body obscured by the other rocks. In the right panel, a skeleton foot juts over a rock, the leg and the rest of the body obscured. The hand and foot are presumably part of the same body. In the foreground, divided by the gutter, a knife stands wedged between rocks. The blade is rusty in 4b, but shiny in 4a.

CAP (in 4b):

To get under the skin.

CAP (in 4a):

To get down to bone.