A few nights after the Sandy Hook shooting, a father heard a strange noise coming from his son’s bedroom. The little boy—he’d seen his teacher and classmates gunned down days before—was pounding on his floor. “I know where the bad guy is,” he said. “I’m beating him up.”

It sounds like a superhero origin story. When Bob Kane drew Batman’s, he posed little Bruce in his bedroom too. “I swear by the spirits of my parents,” said the little boy, “to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals.”

The father of the Sandy Hook survivor said his son was pointing at the floor because the bad guy was in Hell, the same place Bruce’s prayer of vengeance was headed. The child (his name is all over the net, but I’d rather not use it) wants to be a detective when he grows up. He wants to save other children. Meanwhile he’s wearing his old Batman costume to bed.

“People don’t hurt Batman,” his father explained. It’s his way to feel “in control.”

Other shooting survivors take similar comfort in superheroes. An Aurora comic shop owner commissioned a drawing of Green Lantern protecting their local Cineplex 16 to help a twelve-year-old survivor after the shooting there. Three women left the Dark Knight Rises premiere alive because their dates died shielding them from bullets. “He always wanted to be a superhero,” said a family member of one of the victims, “he’s wanting to save someone or do something greater.” One was an honors student “who loved superheroes” and “wrote exceptionally about” Batman and “themes of good versus evil” in his English class.

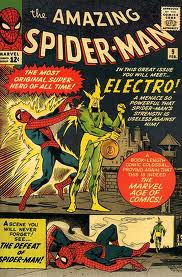

Unfortunately, the shooter was a fan too. Police found a Batman poster hanging in his home and learned that he’d dyed his hair read to look like the Joker. Jeff Kass, author of Columbine: A True Crime Story, theorized the killer “saw himself as some sort of a twisted superhero avenging perceived wrongs.” Hours after the shooting, Kass guessed the suspect “was trying to extract some sort of revenge. Possibly angry at some perceived wrong. This would be similar to the Columbine shooters, and similar to other shootings in the South and West of the United States where people feel compelled to take the law into their own hands.”

I won’t pretend to know the Sandy Hook shooter’s motives, but police suspected he was influenced by a Norwegian, anti-Muslim terrorist who killed 77 people in 2011. That gunman considered himself a kind of superhero too, the self-declared “commander” of his own, one-man “Knights Templar” acting out of “goodness, not evil.” The American Conservative likened him to a “movie supervillain” played by “an unfunny Garrison Keillor.” He titled his manifesto 2083, the year his speculative history of the future ends. The Sandy Hook shooter preferred video games. He may have just wanted a hit a higher death count.

It’s easy to see these killers as supervillains, a kind of Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. It’s even comforting in a way. Wearing a Batman costume, drawing Green Lantern above a mass murder site, calling a person who died protecting someone else a “superhero,” even writing English essays about good and evil, they’re all ways to feel “in control.”

The world is unsafe, but we feel safer when can see events in terms of familiar formulas. And right now, superhero stories are a cultural favorite. Perhaps because they are so violent. I’m not going to suggest that mass murder is the result of mass marketing costumed vigilantes. The relationship between culture and behavior is way beyond my abilities of analysis. But I think we can agree that the relationship is both circular and vicious.

A little boy witnesses murders and devotes his adult life to vengeance. Why is that formula comforting? Isn’t it a deepening of the tragedy?

In The Myth of the American Superhero, John Sheldon Lawrence and Robert Jewett read the Unabomber and the Oklahoma bomber as homegrown terrorists twisting the American monomyth of redemptive violence to anti-government ends. But McVeigh and Kaczinski believed they were acting out of “goodness, not evil.” And they thought violence was the best way of achieving it. It’s part of the American way. The country was born in revolution. Its borders grew through a century of expansionist wars. It remained unified only through civil war. And its second century was shaped by a sequence of foreign wars. Our national heroes, caped and otherwise, champion all that violence.

Is a non-violent superhero even possible? Bruce Willis never throws a punch in M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable. The Scarlet Pimpernel dispatches his arch-nemesis with a snuff box of pepper. But Willis’s enemy is a serial killer, and though Willis quietly strangles him, there’s the promise of more to come. And while the Pimpernel’s enemy is likely to face the guillotine for his failure, the guillotine itself motivates the Pimpernel’s on-going mission. The violence has to continued. It’s part of the formula.

But does it have to be?

A colleague in my English department, Leah Green, spent her summer in a Buddhist monastery in France. She recently pulled me into her office to tell me about a comic book she saw there, The Secret of the 5 Powers. She didn’t bring back a copy (backpacking Buddhist travel very light), but she emailed me the link:

“3 Superheroes of Peace and nonviolence use their powers to change the course of world history.” The members of these non-avenging Avengers include: “Alfred Hassler, an American anti-war superhero, Vietnamese peace activist Sister Chan Khong and Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh.” Instead of supervillains, they fight violence itself and its “seemingly unstoppable escalation.” The creators hope the comic will “challenge the traditional notion of ‘the hero’ and what constitutes heroic action.” They even hope to redefine the “traditional dramatic structure” of superhero comics, showing “there is no good or bad, no white or black. There is only compassion and suffering.”

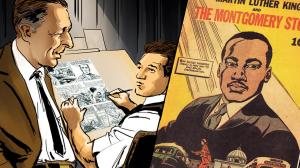

According to a related documentary, not only is Martin Luther King, Jr. a “Superhero,” but he was transformed into one by a comic book: “In 1958, Alfred Hassler had an idea to work with Martin Luther King, Jr. to produce a comic book – a comic book to be distributed in the South to young and old, African Americans and white Americans, to tell the story of the struggle for civil rights in Montgomery.”

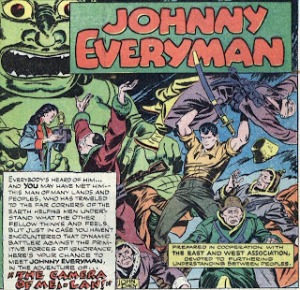

Of course the one-off Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story wasn’t the first comic book about a non-violent hero. DC introduced “Johnny Everyman” into World’s Finest Comics near the end of World War II. The non-costumed Everyman travels the world teaching racial and ethnic tolerance while “devoted to further understanding between peoples.”

Unfortunately you’ve probably never heard of Johnny Everyman. He vanished from the pages of World’s Finest in less than three years. You probably haven’t heard of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story or The Secret of the 5 Powers either. Comics about peaceful superheroes aren’t exactly popular. The genre demands violence. It demands righteous punishment. The superhero formula, the very idea of good versus evil, maintains the problem it pretends to fix. It may be comforting to imagine that for every Joker there’s a counter-balancing Batman, but the reverse would be true too. For every Batman there’s a Joker. The equation maintains unlimited violence. The sense of control is an illusion.

Meanwhile, when my daughter returned to her high school this fall, the lobby included security doors. They’re a new state requirement, a direct fall-out of Sandy Hook. Hanging up pictures of superheroes would be less effective at keeping out gunmen, but probably not by much. The NRA would arm all the teachers, but, as my daughter’s principal told our PTA, “the top focus for security remains administration visibility and relationships.” That’s a boring premise for a comic book, but it might literally save my daughter’s life.