If you’re wondering why you’re reading a bible study during this blog’s weekly schedule, you can blame Chester Brown for creating a commentary-entertainment on the role of prostitution in the Hebrew and Christian Bible.

For those who have spent the last few years living under a rock, let me begin by stating that the provision of professional sexual services has, in recent years, become of paramount importance in the artistic and political life of Chester Brown.

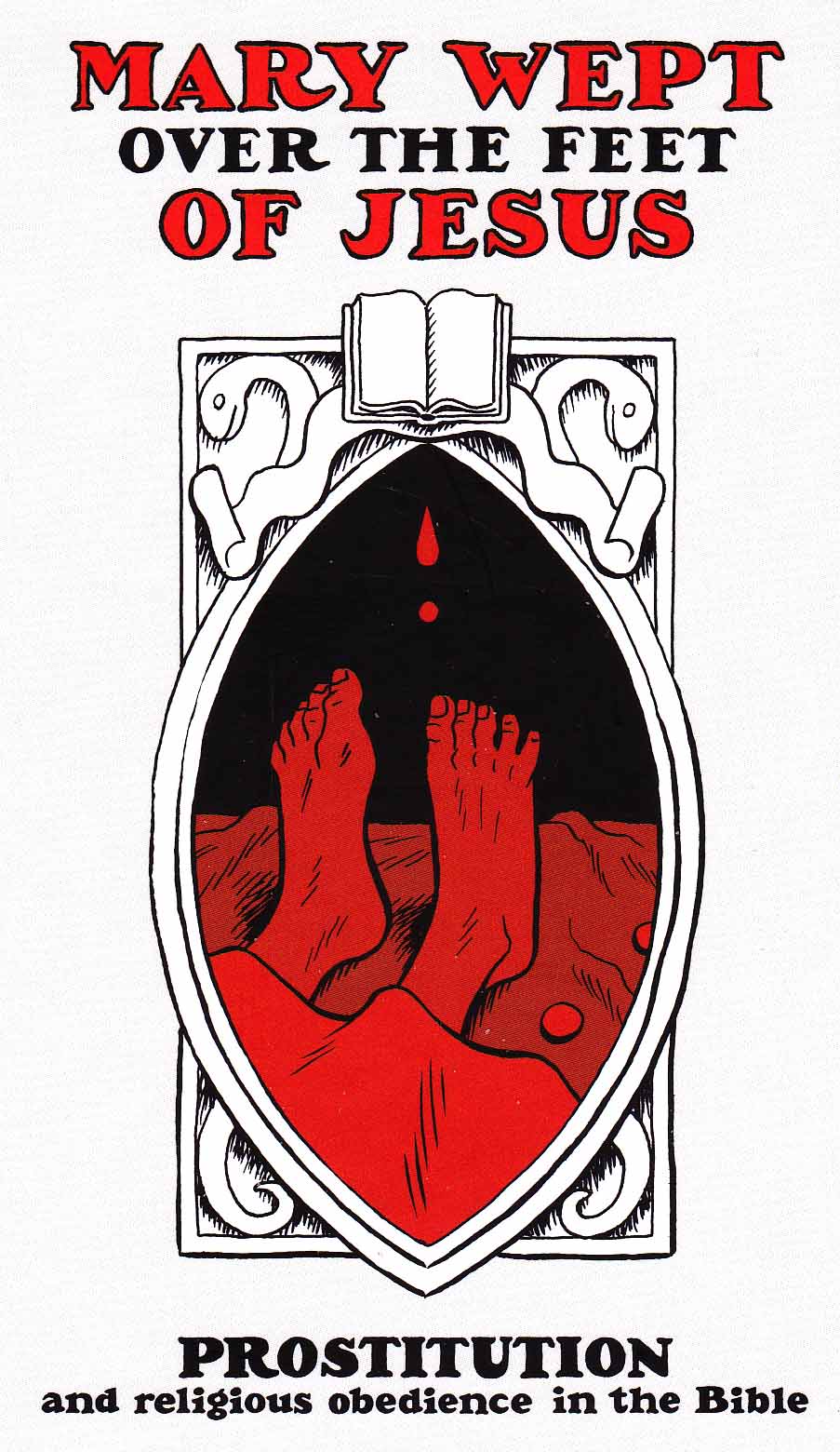

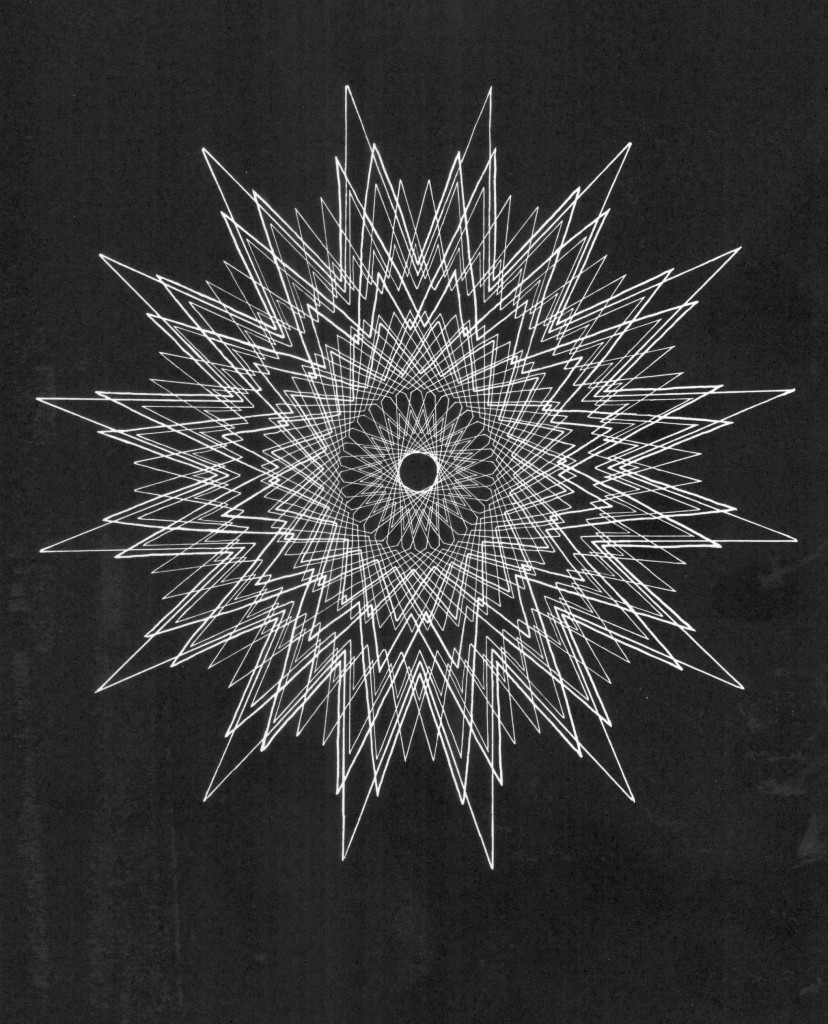

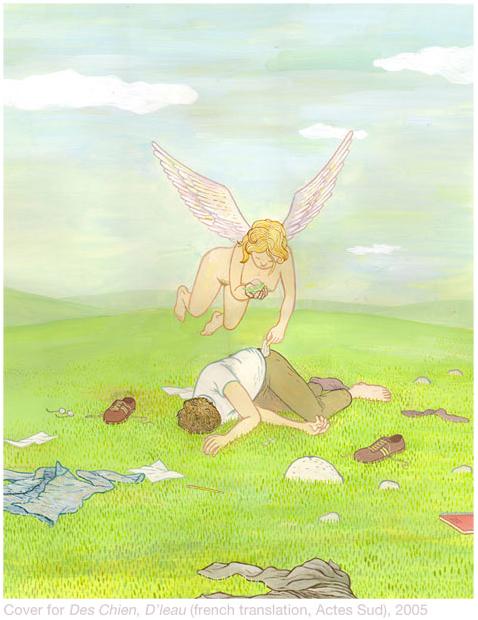

Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus is his hymn of praise and justification for a much maligned occupation. The Mary in question is Mary of Bethany from John Chapter 12, now conflated with the “sinful” woman of Luke Chapter 7:38 who wets Jesus’ feet with her tears. The cover to the new comic is as archly playful as Zaha Hadid’s vaginal design for the Al Wakrah stadium in Qatar. The image is a symbolic representation of female genitalia with Jesus’ feet acting as a symbolic penis and the Bible in the position of the clitoris.

It is an accurate representation of the comic itself—which is thoroughly unerotic and studious. Any ecstasies the reader might hope to derive from Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus will only be derived from a study of scripture.

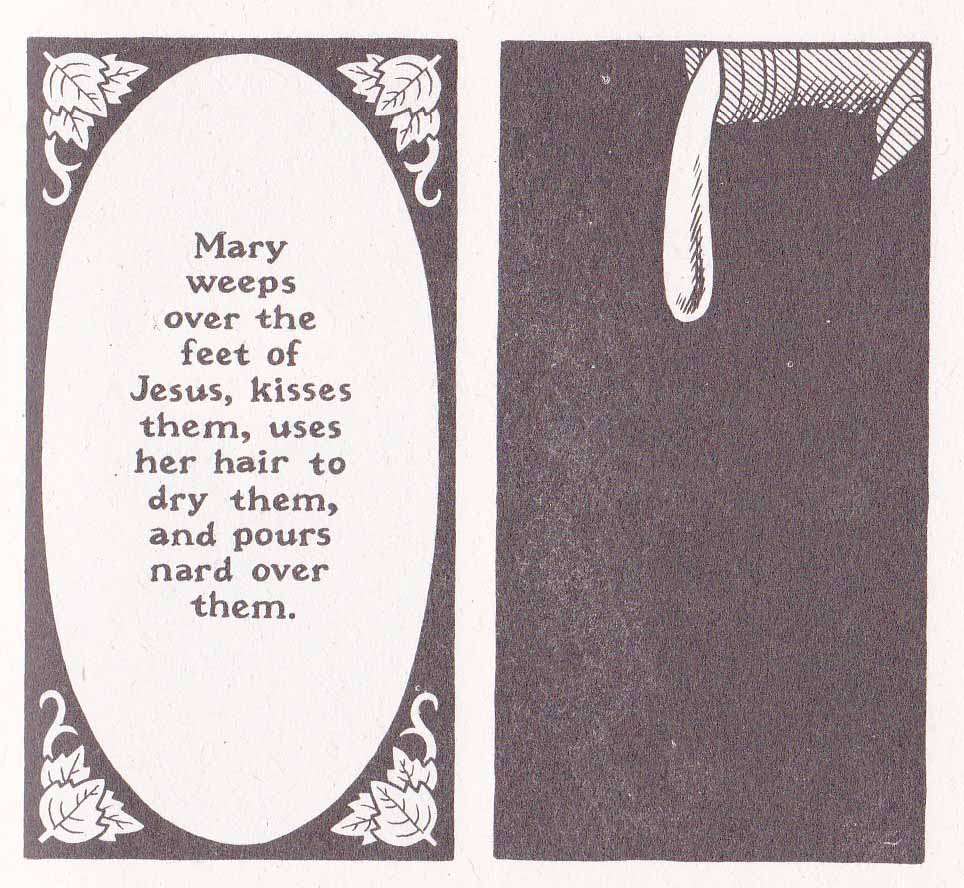

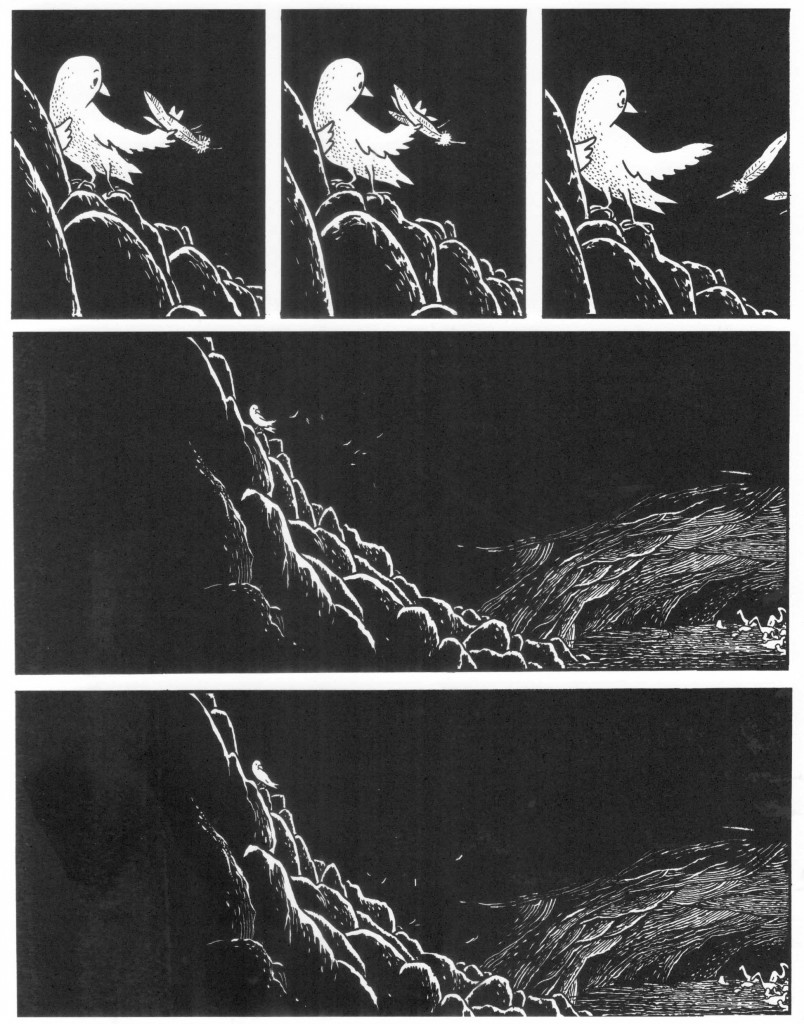

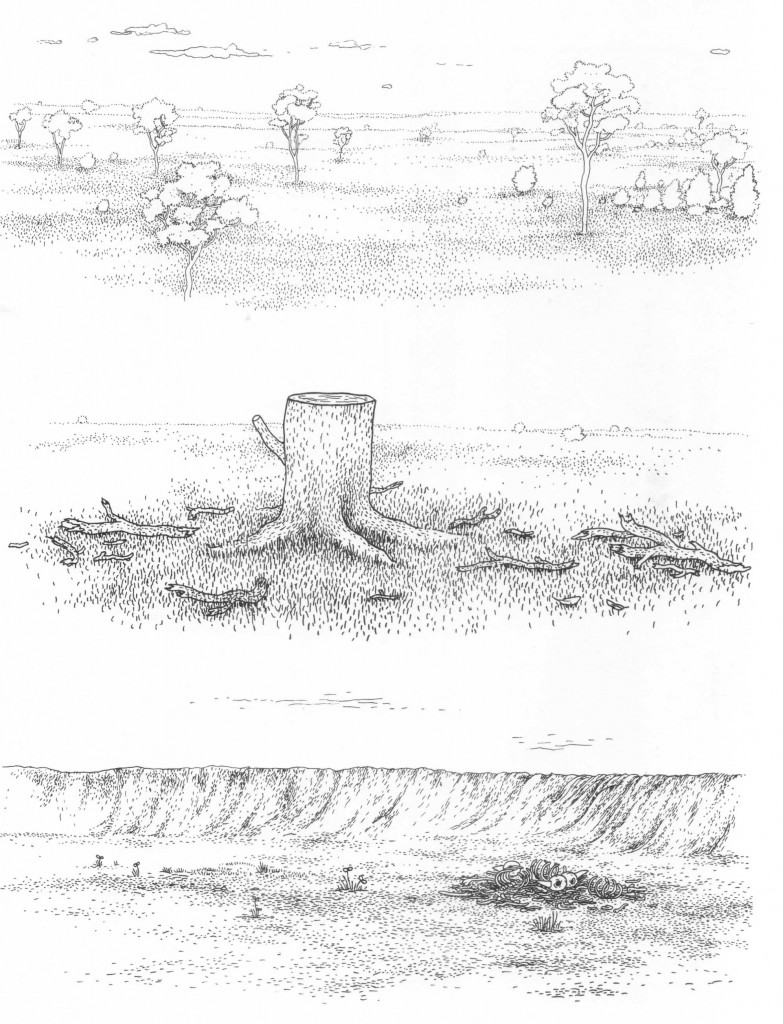

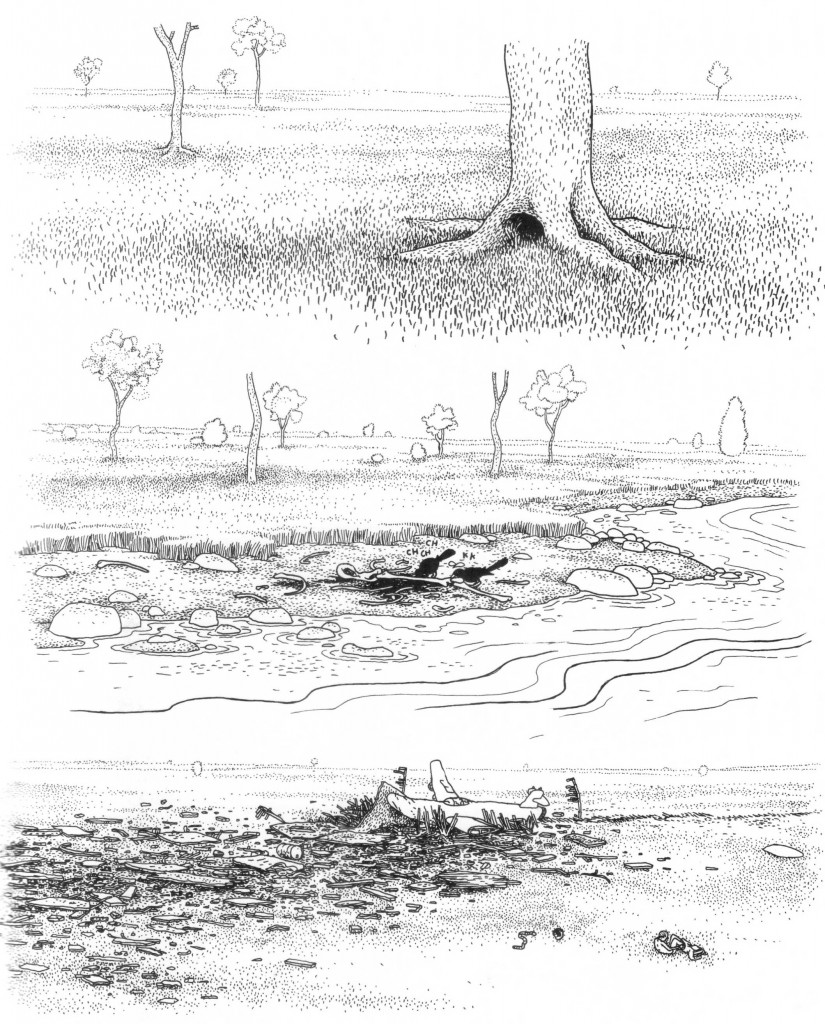

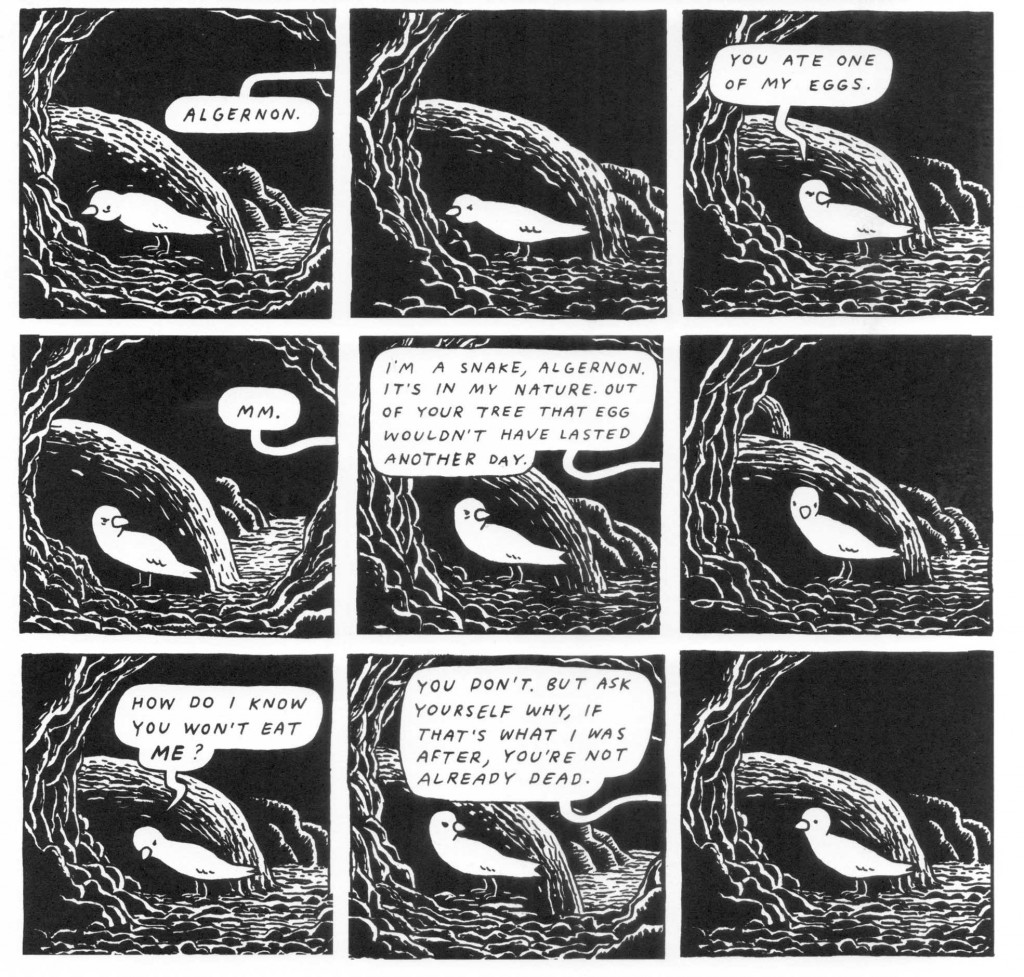

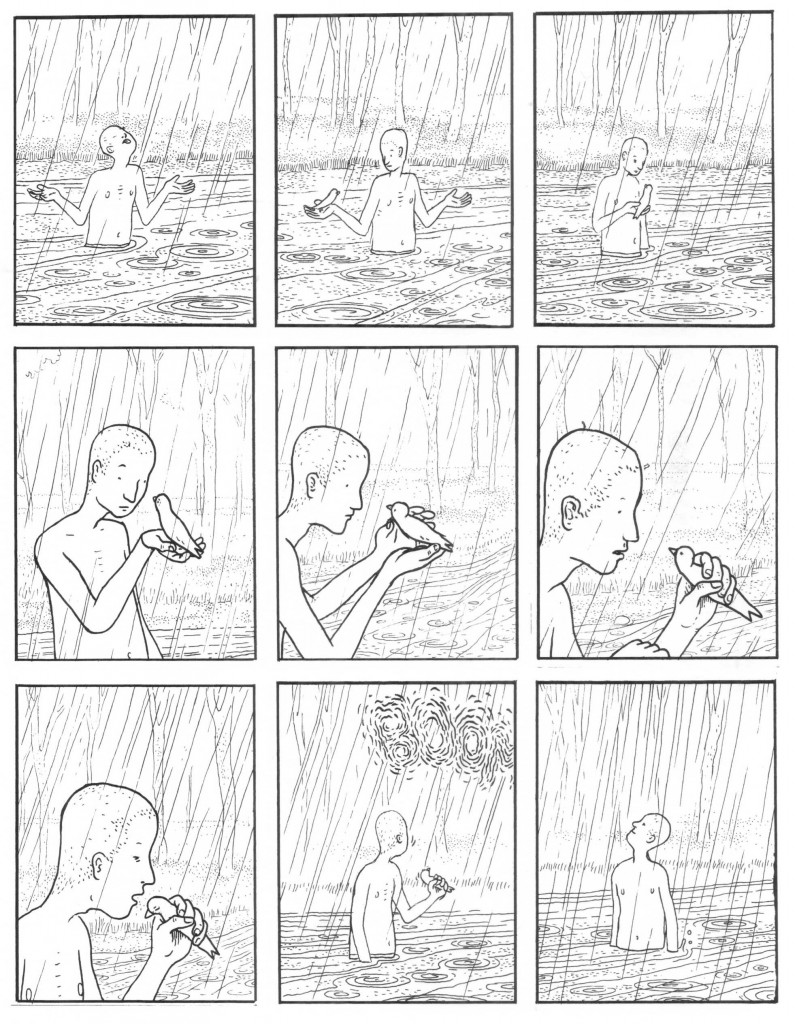

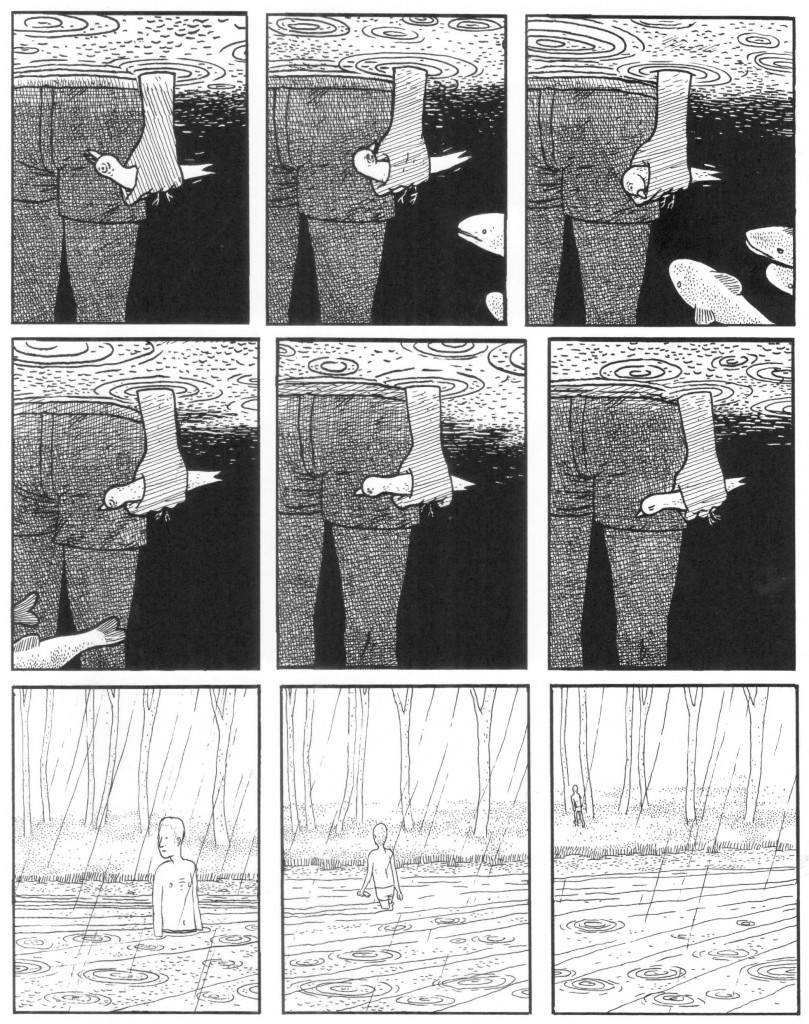

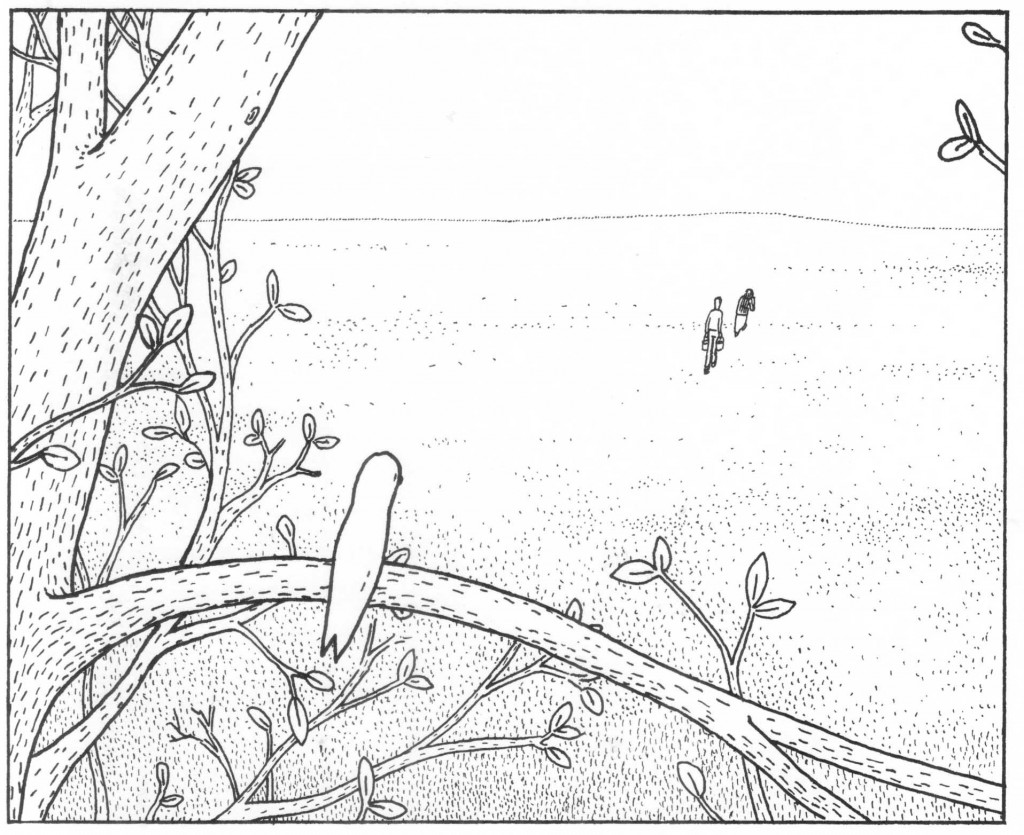

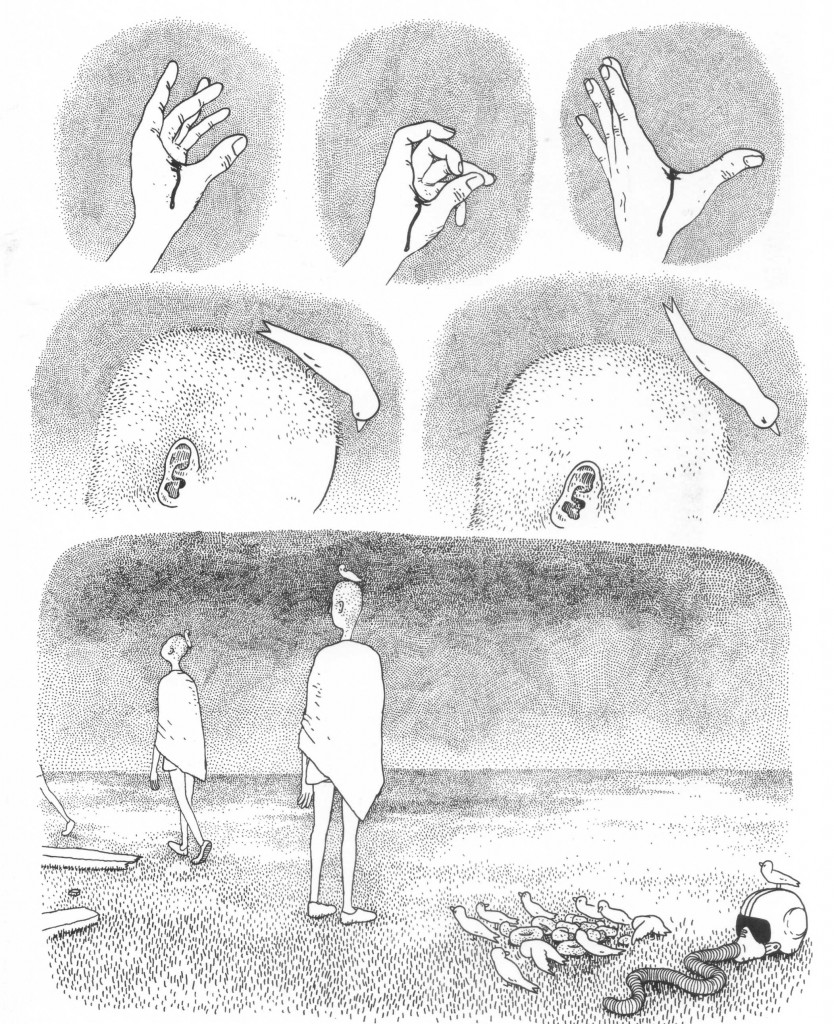

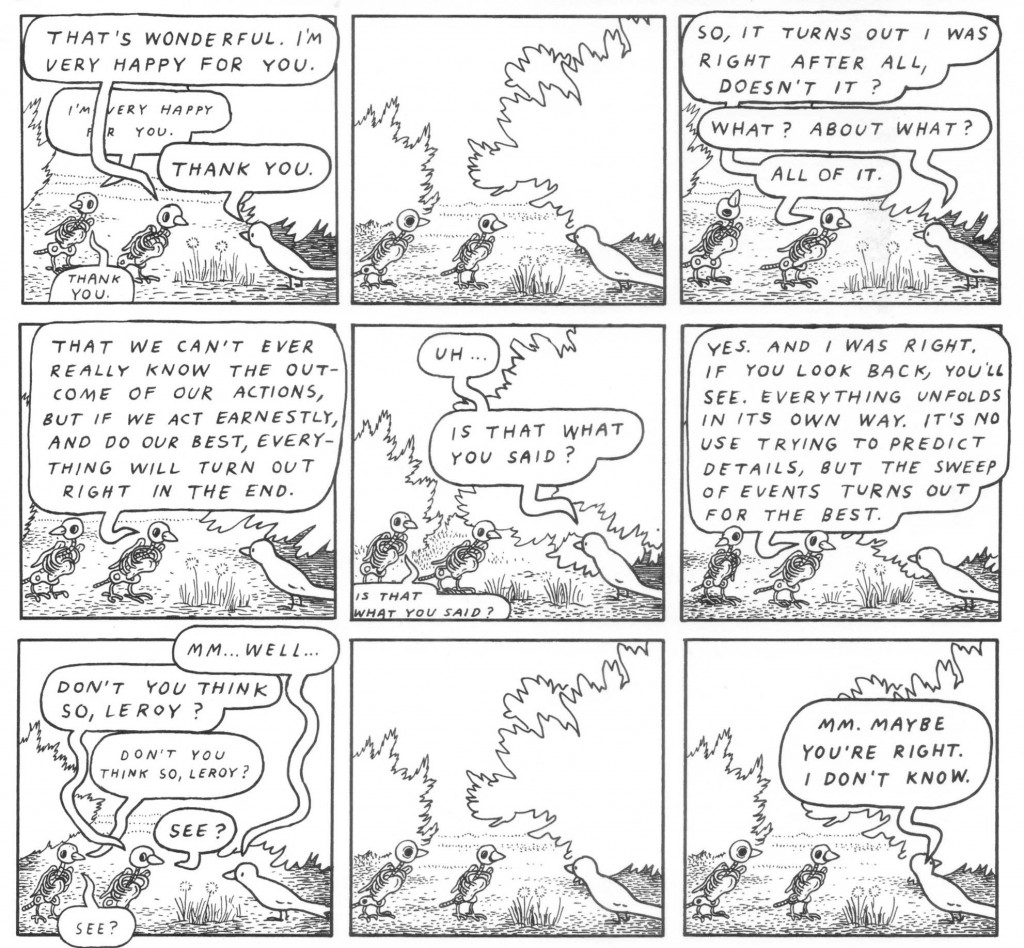

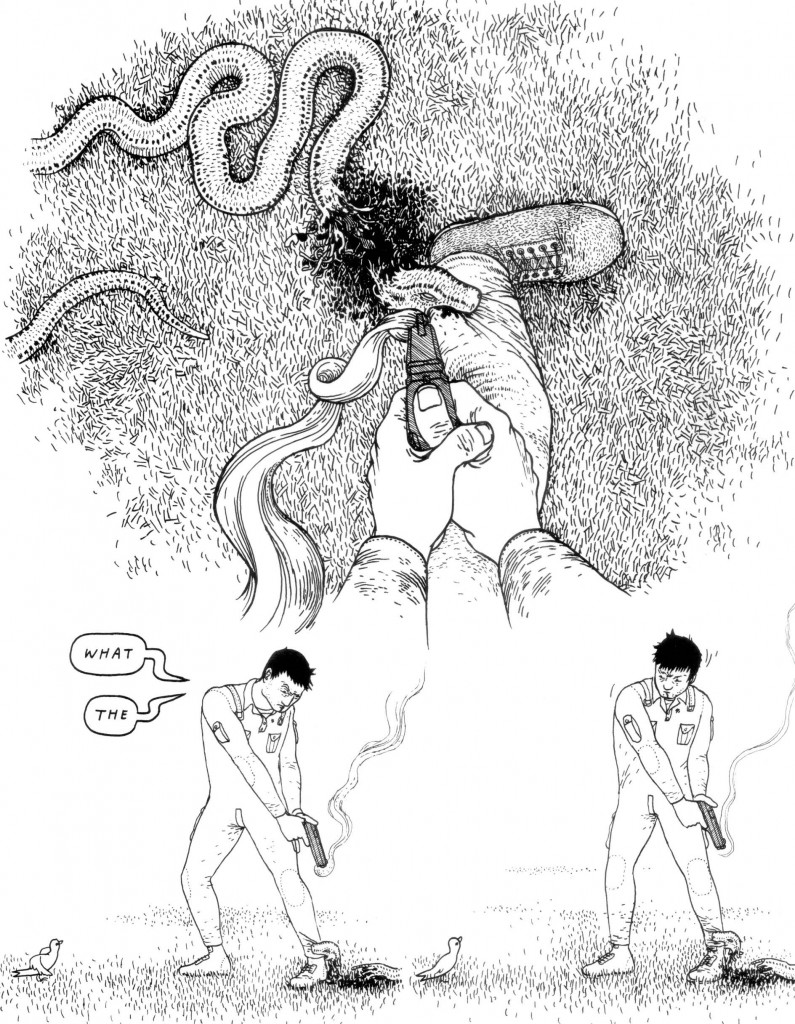

The art mirrors the earnestness of the endeavor and seems ground down into uniform shapes with all gnarly edges removed. Which is not to say that the work is devoid of imagination: there’s the God of Cain and Abel who is pictured as a naked giant with his back constantly turned to us, he holds Abel’s offering in the palms of both his immense hands; Mary of Bethany is only ever seen in silhouette and her actions disembodied into panels of darkness, her tear drops, and nard draining from an alabaster jar. We only see the angry reactions of the men surrounding Jesus. In so doing, Mary of Bethany becomes all the nameless women in the parallel stories found in the Synoptics but more than this, the entire anointment scene plays out as a metaphor for occult sexual intercourse.

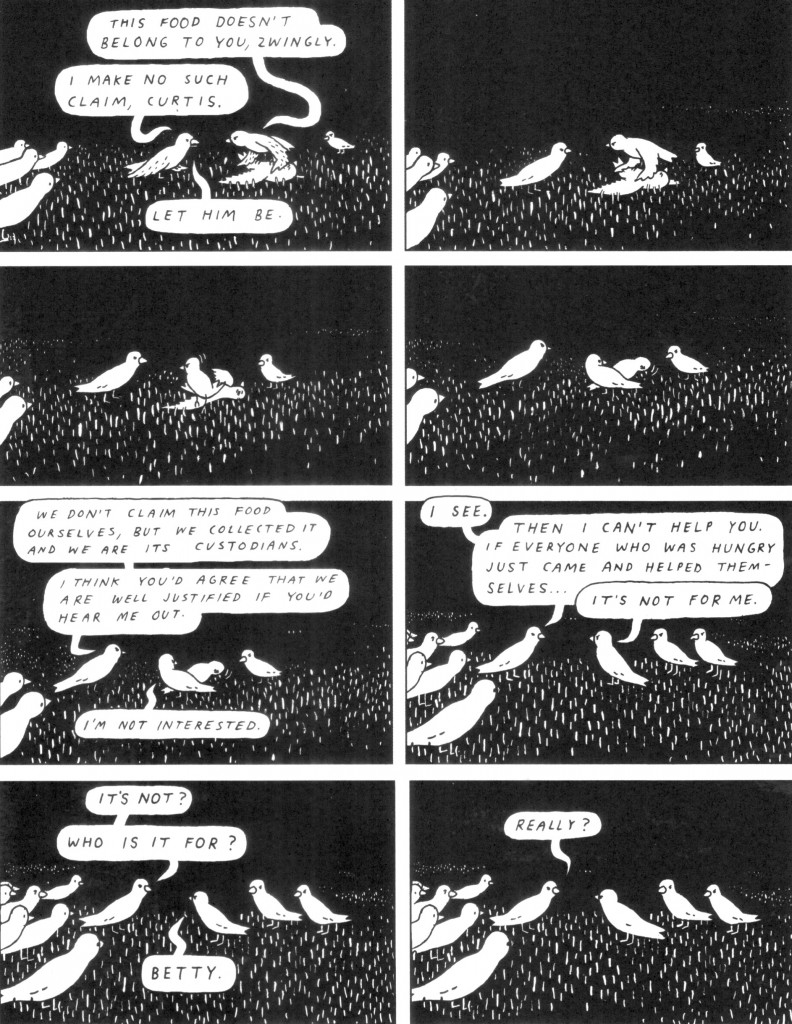

Brown’s comic is concerned with the flexible and mercurial nature of the Hebrew and Christian God, the lack of fixity in his laws; and perhaps his occasional pleasure in those who flout them. If this seems at odds with what you’ve read about God in Sunday School, that would be because it is. Brown’s interpretation of the Bible has always been idiosyncratic, finding the nooks and crannies of hidden knowledge and, in the example which follows, not allowing facts to get in the way of a good idea (to him at least).

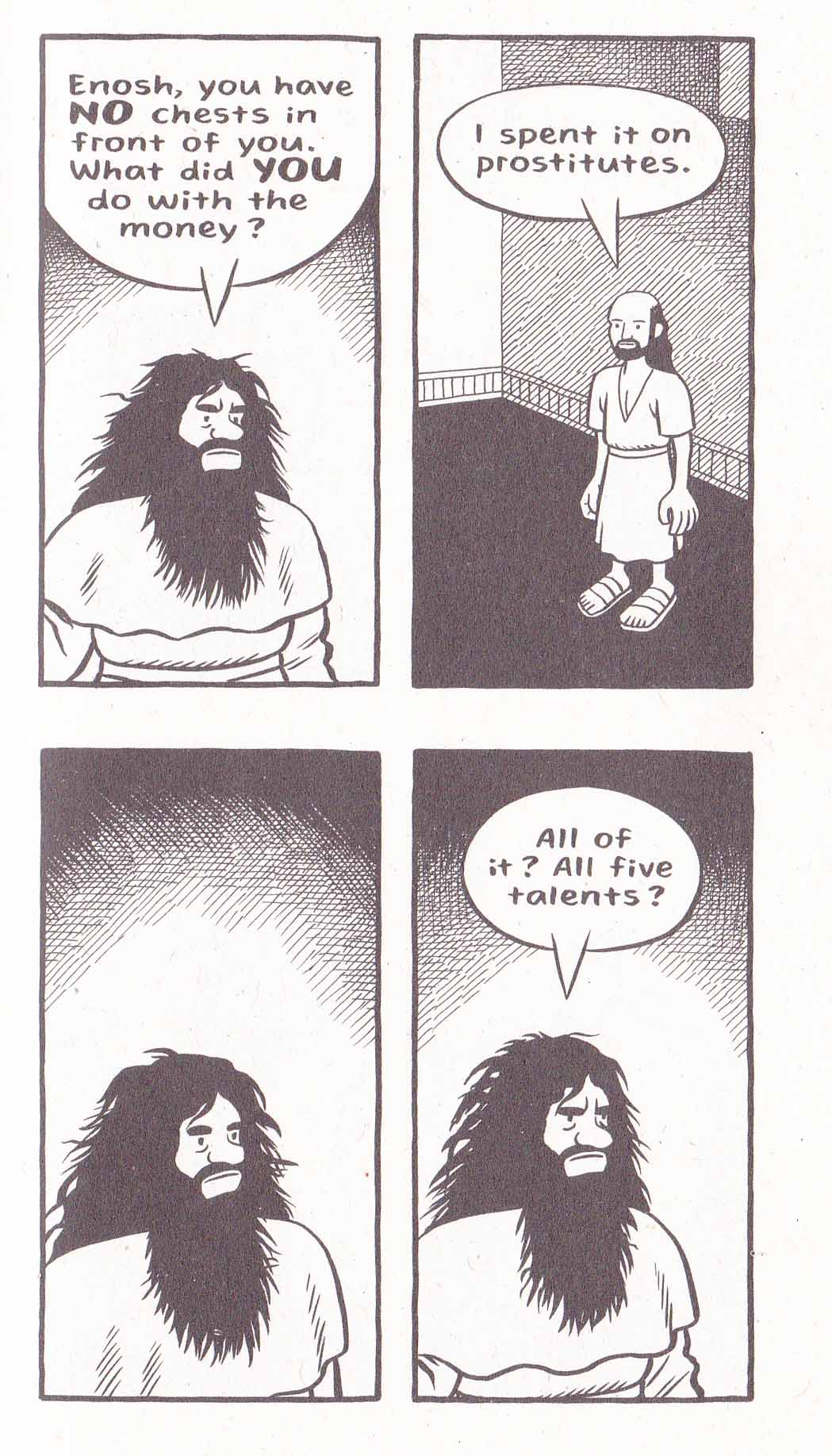

The central story of Mary Wept is “The Parable of the Talents.” This is one version which can be found online:

14 “Again, it will be like a man going on a journey, who called his servants and entrusted his wealth to them. […] 19 “After a long time the master of those servants returned and settled accounts with them. 20 The man who had received five bags of gold brought the other five. ‘Master,’ he said, ‘you entrusted me with five bags of gold. See, I have gained five more.’ 21 “His master replied, ‘Well done, good and faithful servant! You have been faithful with a few things; I will put you in charge of many things. Come and share your master’s happiness!’ […]

24 “Then the man who had received one bag of gold came. ‘Master,’ he said, ‘I knew that you are a hard man, harvesting where you have not sown and gathering where you have not scattered seed. 25 So I was afraid and went out and hid your gold in the ground. See, here is what belongs to you.’

26 “His master replied, ‘You wicked, lazy servant! … […] … 28 “‘So take the bag of gold from him and give it to the one who has ten bags. 29 For whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them. 30 And throw that worthless servant outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’

(Matthew 25:14-30, NIV)

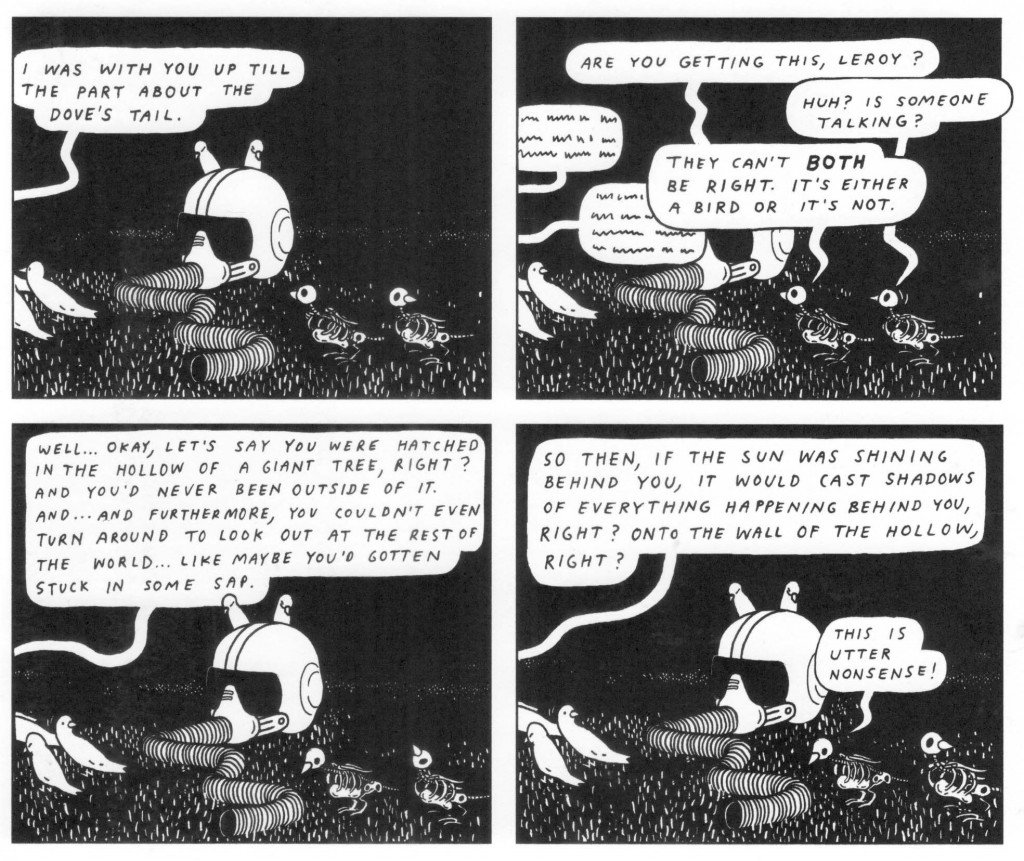

One problem with reading Brown’s copious notes is that they frequently communicate as facts that which is very much in dispute. To wit, in discussing “The Parable of the Talents”, Brown claims with a kind of divine certainty that “the work that we now call Matthew is a Greek translation of an earlier book that was written in Aramaic.” I suppose this represents the assurance of an artist who considers himself a kind of latter day Gnostic.

The idea that at least parts of the Gospel of Matthew was originally written in Hebrew is not a recent invention (see Papias by way of Eusebius) and is held by many Christians but hardly beyond dispute. There is as much reason to believe that this Gospel of the Nazareans (a names which appears only in the ninth century) is an Aramaic translation of Matthew (which is in Greek) or at least takes creative license and inspiration from that canonical book. This Gospel of the Nazareans has only survived in fragments brought down to us by various Church Fathers, and it is a summary of the Aramaic “Parable of the Talents” found in Eusebius’ Theophania (4.22) that provides Brown with his new reading.

From Bart Ehrman and Zlatko Plese’s translation of Eusebius’ paraphrase of “The Parable of the Talents” in Theophania:

“For the Gospel that has come down to us in Hebrew letters makes the threat not against the one who hid the (master’s) money but against the one who engaged in riotous living.

For (the master) had three slaves, one who used up his fortune with whores and flute players, one who invested the money and increased its value, and one who hid the money. The one was welcomed with open arms, the other blamed, and only the third locked up in prison.” [emphasis mine]

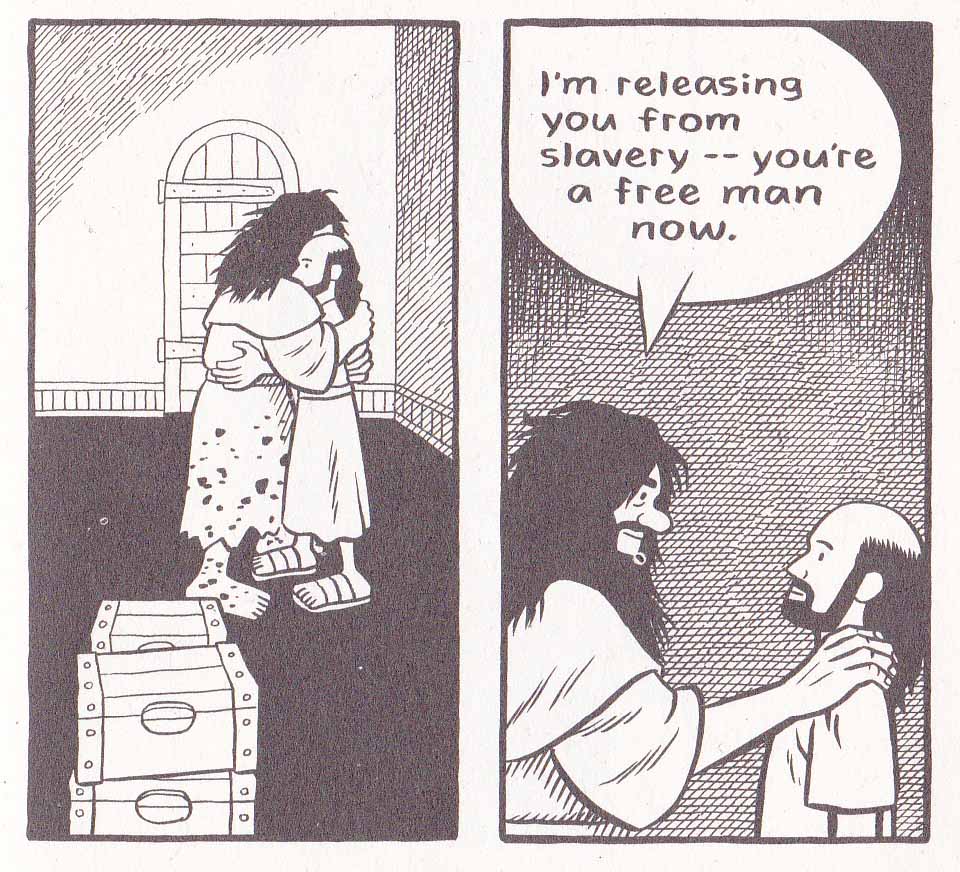

In his quotation of Ehrman in his notes, Brown deliberately leaves out the first section of Eusebius’ summary—that it was the servant who “engaged in riotous living” (i.e. the one who used up his fortune with whores and flute players) that was cast into the outer darkness with the concomitant weeping and gnashing of teeth. In so doing, he elevates the position of that servant in his retelling. In the original text, Eusebius quite clearly excuses the servant who hides the master’s money but in Brown’s rhetoric, it is the “whoring” servant who is rewarded

Brown cites John Dominic Crossan’s The Power of Parable as the primary source of his inspiration with regards his interpretation of “The Parable of the Talents” but while Crossan does provide the same reduced quotation from Eusebius, he obviously knows the whole and is clearly at odds with Brown’s reading:

“The version of the Master’s Money was presented in elegant reversed parallelism—a poetic device…But that structure means that that, of the three servants, the squanderer is “imprisoned’…The hider is, in other words the ideal servant.” (Crossan)

For Crossan, the parable is primarily about the conflict between the “Roman pro-interest tradition” and the “Jewish anti-interest tradition”; a challenge to live in accordance with the Jewish law in Roman society. Brown’s adaptation, on the other hand, seems to have been constructed out of whole cloth. If Brown’s adaptation of the “Parable of the Talents” has no historical or textural basis, then what are we to make of it? Perhaps Brown sees himself as a kind of mystic who has divined the true knowledge and the error in Eusebius’ (and presumably Crossan’s) prudishness.

More importantly, why would Brown even require a Christian justification for prostitution? Brown provides the answer to this in his notes—he considers himself a Christian though an atypical one. Moreover he considers secular society’s disapproval of prostitution (“whorephobia”) an unjustifiable legacy of poor Biblical interpretation, not least by a rather inconvenient person called Paul. Brown lives in Canada where it is illegal to purchase sexual services but technically legal to sell them. In this Canada has adopted the longstanding Swedish model, of which The Living Tribunal of this site (aka Noah) has grave misgivings, mostly because sex workers report that it puts them at risk.

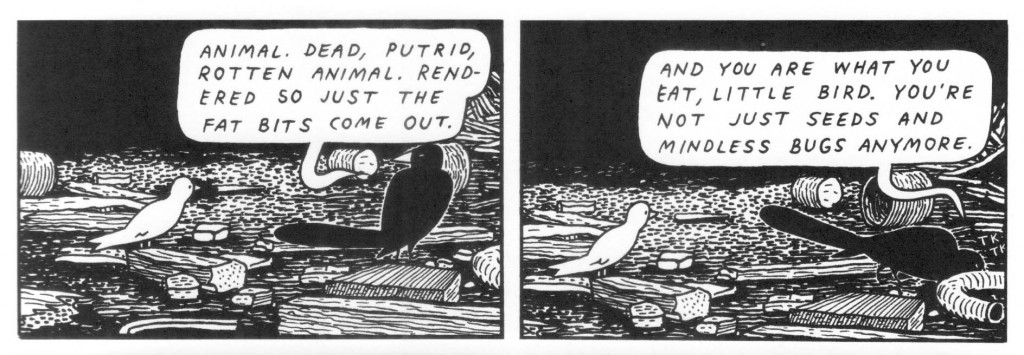

Brown uses the story of Jesus’ anointment at Bethany to highlight the vulnerability of women in Jesus’ time. The title of Brown’s comic is a reference to the story told in Luke 7:36-50 where a (nameless) woman in the city “who was a sinner” bathes Jesus’ feet with her tears, drys them with her hair, and anoints them with ointment. The story has parallels with the story of Mary of Bethany’s anointing of Jesus’ feet in John 12:1-8, and Mark 14:3-11 where an unnamed woman pours expensive nard on Jesus’ head (“Truly I tell you, wherever the good news is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will be told in remembrance of her.”)

After a period of vacillation, Brown has come down firmly on the idea that the woman in question (Mary of Bethany included) was a prostitute. By his estimation, the various versions of this story are not redactions retold for different ends but the exact same story from which the individual elements of each can be combined to form a richer more instructive whole.

Feminist interpretations of Luke (among others) differ greatly on this subject. The evidence for the woman’s sexual sin tends to come down to her exposure of her hair in public, her intrusion into the house of Simon, and her description as a “woman in the city”— all of these points have met with equally forceful rebuttals in recent years. These feminist readings focus on the sexualization of the woman and the fixation on her sin. They question scholars “who choose predominantly to depict her as an intrusive prostitute who acts inappropriately and excessively” despite the gaps in Luke’s text which allow a variety of readings. It is these gaps which opens this famous episode to a variety of rhetorical uses.

One of the great feminist readings of the New Testament, Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza’s In Memory of Her, concerns itself with the historical erasure yet centrality of women in the Gospels. At one point, Martha (Mary’s sister) is seen as a candidate for “the beloved disciple” when John places the words:

“Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.” (John 11:27)

…into the mouth of Martha as the climatic faith confession of a ‘beloved disciple’ in order to identify her with the writer of the book. To Fiorenza, Mary’s action of using her hair to wipe Jesus’ feet is “extravagant” and draws comparisons to Jesus’ own washing of his disciples’ feet in The Gospel of John. Also of note is the decidedly male (Simon, the disciples, Judas) objection to her actions in every instance which is rebuked by Jesus.

While most sex workers are in fact women, Brown seems less interested in recovering the central status of women in the Bible. He has a somewhat different feminist (?) mission. Is it possible to be a sex worker and still be a good Christian? Even Brown seems to admit that it is impossible to reconcile prostitution or any form of sexual immorality with Biblical laws and Jesus’ admonitions. His new comic simply charts the curious areas where the profession turns up in the Bible and where its position in that moral universe is played out most sympathetically. While Jesus commands the woman taken in adultery to go and sin no more, I know not one Christian who has not continued to sin in some shape or fashion. Shouldn’t we be exercised about our own sins before those of perfect strangers? One would have to posit that the sin of sexual immorality is greater than all other sins (including our own) for one to be primarily concerned about its deleterious effects.

Brown’s position as a Christian in Mary Wept is that God’s laws are not immutable. Instead of a life of submission to curses and obedience to laws, he has chosen the “life of the shepherd” as espoused in Yoram Hazony’s The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture:

“…a life of dissent and initiative, whose aim is to find the good life for a man, which is presumed to be God’s true will.”

For Hazony, piety and obedience to the law are “worth nothing if they are not placed in the service of a life that is directed towards the active pursuit of man’s true good.” One presumes that Brown feels that he has found “man’s true good” in the sexual and personal freedoms afforded by prostitution. Whether he has found woman’s “true good” remains a far more controversial question.