About a year ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration unveiled a series of nine large cigarette package labels that add vivid images to existing text-only warnings about the dangers of smoking. These new “enhanced warning labels” include pictures of corpses, a diseased mouth, lungs, and throat, and infants threatened by second-hand smoke followed by phrases such as “Cigarettes cause cancer” or “Smoking can kill you” and an 800 number for help.

About a year ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration unveiled a series of nine large cigarette package labels that add vivid images to existing text-only warnings about the dangers of smoking. These new “enhanced warning labels” include pictures of corpses, a diseased mouth, lungs, and throat, and infants threatened by second-hand smoke followed by phrases such as “Cigarettes cause cancer” or “Smoking can kill you” and an 800 number for help.

The labeling system, part of the Family Smoking Preventing and Tobacco Control Act of 2009, was to go into effect this September until a group of tobacco companies sued to block the requirement. While one federal judge ruled earlier this year that the warnings violated the free speech of the cigarette makers and granted a preliminary injunction, an appeals court in a related case disagreed, making it likely that the issue will end up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

I was listening to a report about the ongoing case on NPR two weeks ago and I was particularly struck by the kind of language that the judges, federal officials, anti-smoking advocates, and constitutional experts used to describe the images and their impact on consumers.

“It’s going beyond I think what is necessary,” says David Hudson, a scholar at the First Amendment Center in Nashville, Tenn. “It’s just so in your face, so graphic, these images — it’s just simply too much.”

[…]

“The picture of somebody that is dying from tobacco can be an accurate representation of the health effects of smoking, even if it evokes an emotional reaction,” [Matt Myers, from the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids] says. (NPR)

How do we go about weighing what is accurate and emotional when it comes to the information that these images convey? And how do we decode a sight that can’t be put into words because it’s just simply too much? I can’t help but think that the Supreme Court should call Charles Hatfield to testify about these very questions, but until then…it might be useful to consider how comics studies might benefit from a discussion about cigarette warning labels.

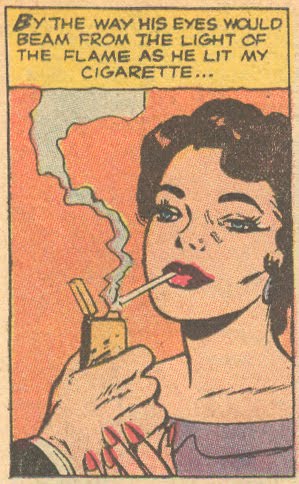

For one thing, the issue allows us to think more carefully about how assumed notions of perceived and received images operate in practice. The news reports about the labels consistently highlight public officials, corporations, and advocacy groups in the act of measuring qualitative differences between this:

And this:

Confronted with the new labels, these sound bites and legal opinions appear to revolve around concerns over visibility, accuracy, and provocation: how we see the images, how we interpret them,and how they make us feel.

On Visibility: Thomas Glynn with the American Cancer Society refers to the old labels as “invisible” and according to CNN, “people have become immune and don’t really ‘see’ them any more.” Other FDA officials express the hope that more visible warnings might counter the tobacco’s industry’s well-funded efforts to downplay the harmful effects of cigarette addiction through colorful ads of their own. The concerns on both sides of the issue bring to mind a number of strategies that comic book writers and artists deploy to maintain the attention of readers and to convey subtle nuances of meaning. But as the public becomes exposed to the cigarette warnings, couldn’t even the novelty of the increasingly graphic portrayals reach a new tolerance threshold?

On Accuracy:In deciding matters of constitutional freedom, the district court judge that blocked the labels was less concerned with matters of perception and sustained attention, and more troubled by the way the images appeared to cross the line between “information” and “advocacy.” Judge Richard Leon wrote that, “the Government fails to convey any factual information supported by evidence about the actual health consequences of smoking through its use of these graphic images.” The image of a body on an autopsy table, meant to represent the 443,000 deaths caused by tobacco, left too much room for interpretation, claimed the judge. (NPR) One wonders if a similar logic could be applied to the verb cause in the text-only label that declares: “Smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease…” Could we scrutinize the different variables and contingencies that inform the FDA’s word choice here, or do words discourage us from making the kind of assumptions that images do?

On Provocation: The tobacco companies defend their legal right to sell cigarettes by arguing that the government labels actually go beyond advocacy to shame. While the word emphysema objectively informs, the image of a lung, brown and marbled with the disease, repulses in ways that project negatively upon the consumer. Consider the statement from cigarette maker R.J. Reynolds:

“The anti-smoking message is not intended to provide information that smokers and potential smokers can consider rationally in weighing the risks and perceived benefits from smoking. Rather, it plainly conveys — through graphic images and designs intended to elicit loathing, disgust, and repulsion — the government’s viewpoint that the risks associated with smoking cigarettes outweigh the pleasure that smokers derive from them and, therefore, that no one should use these lawful products.” (CNN)

Interestingly enough, the appeals court panel that rejected this view also commented on the impact of the graphics, “finding that the fact that the specific images might trigger disgust does not make the requirement unconstitutional” (Huffington Post). I can’t help but think of the “severed head exchange” between EC Comics publisher Bill Gaines and Senator Kefauver in the 1954 Senate Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency when I read about judicial decisions that distinguish between perceived levels of disgust.

Ultimately, each group brings a different set of investments to the debate over the cigarette labels in ways that reveal fascinating insight into how words and images are privileged. Ironically, the fact that the new labels contain both pictures and text is often overlooked; each warning is dependent on the other, as well as the packaging, to convey the risks and pleasures of the product inside. (It is also worth noting that not all the new labels are photographs, at least one is a comic art illustration of a premature infant.) How does the interplay of visual and verbal elements in comics help us to think through the debate over enhanced cigarette warning labels?

___________

Cross posted at “Pencil Page Page.” Comics image above via “Sequential Crush.”